William the Conqueror (c. 1027-1087), also known as William, Duke of Normandy, led the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 when he defeated and killed his rival Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings. Crowned King William I of England on Christmas Day 1066, he secured his new realm after five years of hard battles against rebels and invaders.

Continuing to reign over Normandy, William's policies of land redistribution amongst the Norman elite ensured the history of both England and France would be inseparable in the following centuries. An accomplished diplomat, gifted military commander, and ruthless overlord, William died of natural causes in 1087 at Caen, Normandy where his tomb still lies.

Family & Personal Life

William was born in Falaise, Normandy c. 1027. He was the illegitimate son of Duke Robert I of Normandy (1028-1035), hence he is sometimes referred to as William the Bastard. William's mother was Herleve of Falaise, daughter of a wealthy merchant in Rouen who also performed the duties of a chamberlain to the ducal court. William's half-brothers (they shared the same mother) were Odo of Bayeux, the bishop of that city and future Earl of Kent, and Robert (future) Count of Mortain. In 1053 (or 1050 in some sources) William married Mathilda (d. 1083), the daughter of the Count of Flanders and the niece of Henry I of France (r. 1031-1060) in a marriage which conveniently cemented the burgeoning diplomatic relations between the three regions. Together they would have four sons and four (or five) daughters.

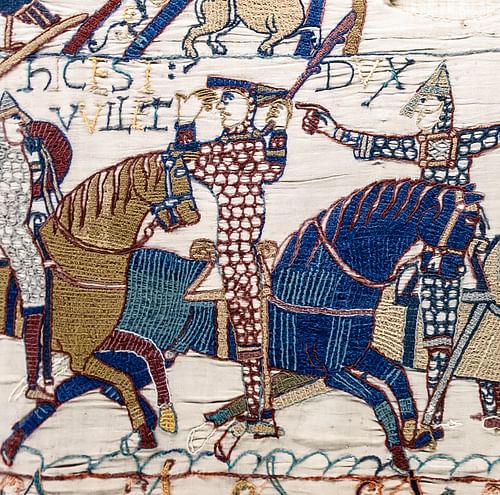

William of Poitiers, an informed but obviously pro-Norman contemporary, describes the young duke in the following glowing terms in his 11th-century chronicle, History of William the Conqueror:

Now at last the most joyful and longed-for gladness dawned for those especially who desired peace and justice. Our duke, already adult in sagacity and bodily strength if not in years, took up the arms of knighthood whereat a tremor ran through all France. Armed and mounted he had no equal in all Gaul. It was a sight at once both delightful and terrible to see him managing his horse, girt with sword, his shield gleaming, his helmet and his lance alike menacing.

(Allen Brown, 18)

The description may sound like a eulogy but it is perhaps significant that the seal of the duke was a knight on horseback, the first such device employed by a European ruler and much-copied thereafter. William had other talents besides military ones, though, as he would show throughout his career. The duke was a meticulous planner, a master of seizing political opportunities for maximum gain, and an able administrator. William was also a great lover of hunting, and the strict forest laws he would much later introduce into England were, in part, aimed at ensuring his beloved deer were not molested by poachers. William also had a reputation as a fine archer.

Duke of Normandy

When Duke Robert died in Asia Minor while on pilgrimage, William became the Duke of Normandy in 1035. Fortunately for William, his father had already secured oaths of loyalty from his barons regarding his son as his chosen heir. In reality, though, William was still only a child and so a guardian ruled in his name, Gilbert of Brionne. In 1040, a civil war broke out in Normandy when Gilbert was murdered and rebel barons sought to expand their own lands, often by building castles. It would take seven long years for William to sort out his dukedom but he could at least call on powerful friends, notably the Archbishop of Rouen, William's uncle Mauger, and the powerful husband of his mother, Herluin de Conteville. Finally, in 1047 and with the help of Henry I - who sought to protect the vital trade routes through Normandy and the future of one of his vassals - the rebels suffered a significant defeat at Val-ès-Dunes near Caen. There were still more battles to come and some notable sieges, including a three-year effort against the castle of Brionne, held by Guy of Burgundy, which ended in success for William.

The next 20 years would see a great increase in the power of the dukedom, not without a struggle, but the years of war would train William into one of the most formidable military strategists and field commanders of the Middle Ages (and also one of the luckiest ones). Embarking on a sustained campaign of war and expansion, especially against long-time rivals like Flanders and Anjou, William used any method available, including terror and mutilations as well as arranged marriages of political convenience for key members of his inner circle, to eventually become the most powerful noble in France.

William was now almost too powerful and, in 1053, the French king chose to side with the Norman duke's uncle, William of Arques, then a rebel baron. The duke, though, attacked the enemy's supply train, and his uncle was obliged to surrender. There had to be a robust defence of Normandy in 1054 when a French force, looking for revenge for the events of the previous year, invaded. The French army was defeated at Mortemer, and again, against the same enemy but with an even more emphatic result, at Varaville in 1057. King Henry barely escaped with his life at Varaville; the French king, stranded from half his army by a river in flood was furious but he could do nothing to prevent a massacre. William was unstoppable. In the coming years, he added to his dukedom several notable personal dependencies, including the Channel Islands (aka Îles Normandes), and the duchies of Brittany and Maine. This, along with the death of Henry of France and the fact that his young son was under the guardianship of William's father-in-law, Robert of Flanders, meant William's duchy was secure from its neighbours. The duke's ambitions could now extend beyond France.

William set his sights on the throne of England but, still technically a vassal to the King of France, he could not attack without some prior justification and diplomacy. The Norman barons also had to be persuaded of the value of invading England but the promise of land, titles, and riches proved sufficient motivation there.

William proposed a justification for his invasion of England with no less a claim than he was the rightful king. This claim was based on the Duke's relationship with Edward the Confessor, king of England from 1042 to 1066. Count Richard I of Normandy was Edward's grandfather and William's great-grandfather. William put it around that Edward, without children of his own, had once promised the Norman he would be Edward's official heir. As it turned out, on his deathbed Edward selected the Anglo-Saxon Harold Godwinson, a member of the enormously powerful Godwine family and then the foremost military commander in England, as his successor.

In another twist to William's claim (at least according to Norman chroniclers), Harold had visited Normandy c. 1064, where he had been captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and then handed over to William (who put him to good use in his battles to subdue Conan, the count of Brittany). A condition of Harold's release was that Harold promised to become William's vassal and prepare the way for an invasion. Thus, William felt wronged when Harold was crowned Harold II of England in January 1066. The Anglo-Saxon sources dispute much of this story but it was enough to convince other European kings that William had some right to invade. In addition, William even received the blessing of the Papacy, which had been at loggerheads with England's Archbishop of Canterbury for some years, refusing to acknowledge he had any right to the role. Convinced he had both right and God on his side, William made meticulous preparations for an invasion of southern England in the summer of 1066.

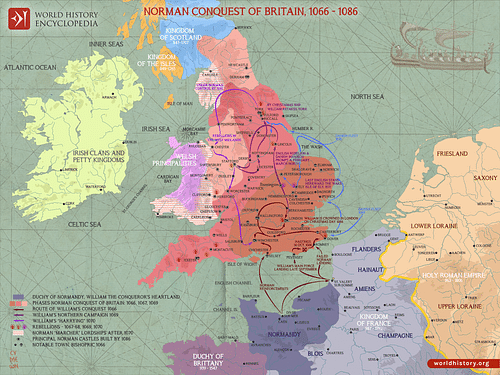

The Norman Conquest of England

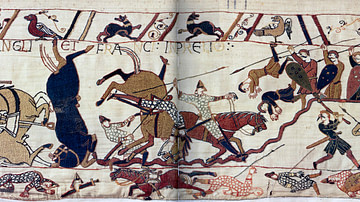

It must be said that William was rather lucky in his invasion of England because his enemy Harold II was obliged to face another invasion just a few weeks before the Conqueror arrived, this one by Harald Hardrada, the king of Norway (aka Harold III, r. 1046-1066). Harold saw off Harald at the Battle of Stamford Bridge near York on 25 September 1066 and then marched south to face William's army of 5-8000 men including 1-2,000 cavalry. The two armies, probably similarly sized, clashed at Hastings on 14 October. With archers and cavalry against Anglo-Saxon infantry, William was victorious and Harold was killed. When reinforcements arrived from Normandy, William marched on London, first taking such key strongholds as Romney, Dover, Winchester, and Canterbury. Many of the Anglo-Saxon nobles and the archbishop of Canterbury swore allegiance to their new king, who was crowned on Christmas day 1066 in Westminster Abbey.

Now William I of England and Duke of Normandy, the Conqueror had to fight on for five more years before England was fully subdued. Scorched earth tactics, building hundreds of motte and bailey castles, imprisonments and mutilations of rebels at such key cities as Exeter and York, the seeing off of two mini-invasions from Ireland by Harold's sons, the quashing of a Danish-rebel force in East Anglia, and the complete redistribution of estates into the hands of loyal Normans, all ensured William did eventually secure his new realm. The church was restructured, with Norman bishops getting the plum jobs, many important religious centres were moved closer to cities, and new cathedrals were built such as those at Winchester, York, and Canterbury.

Post-Conquest Reign

William might have got himself a rich new kingdom but he did not ignore his lands in France, and he frequently returned there, often leaving England to be ruled by his half-brother Odo of Bayeux, Earl of Kent and his close friend William FitzOsbern, Earl of Hereford. Indeed, sometimes William had to fight to maintain his lands in France, notably against Fulk, count of Anjou in 1073. Philip I, king of France (r. 1060-1108), also became ambitious to nibble at William's dukedom and support rebels within it, notably in Brittany. There was, too, a failed rebellion in England in 1075. Led by Ralph de Gael, this minor conspiracy was put down without William even having to leave Normandy. Still, it was a sign of the inherent strains involved in having to juggle both a kingdom and a dukedom with plenty of nobles ever-eager to expand their interests in one or the other or both territories.

Then William's long run of military victories came to a sudden end. In 1077 the duke was defeated near Dol in Brittany. Within a year another rebellion broke out, this time led by William's own eldest son Robert, who felt he was not being given enough power of his own. Again, Philip of France took the opportunity to destabilise the situation and gave a castle - Gerberoi on the border with Normandy - for Robert to use as a base. William attempted a siege of Gerberoi, but his son seems to have learned rather too well the ways of war from his father, and William was defeated in a field engagement. Fortunately, William and Robert were reconciled and the younger man was needed, too, as he was sent to repel the raids into Northumbria coming from Scotland in 1079.

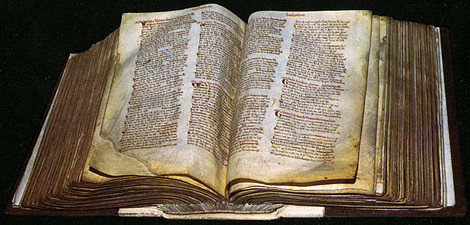

Domesday Book

Far from being a mere warlord, William was an able administrator. In 1086-7 the king ordered a comprehensive survey and record of all the landowners, property, tenants, and serfs of England. After the changeover of the Anglo-Saxon elite to Normans and massive redistributions of estates, the king was likely interested to know who owned what in his kingdom. The findings of the survey would be assembled into a single document, the Domesday Book (actually two books because one, Little Domesday, seems to be a more detailed record which was never condensed into the format of the larger volume, Great Domesday). It may be that Domesday Book was compiled so that a new tax could be accurately levied and to ensure landowners provided the correct feudal military service expected of them. The record could then be a very useful tool to ultimately pay for an army in order to face the threat of a Danish invasion of England which had looked imminent in 1085. Domesday Book, the most comprehensive survey ever undertaken in a medieval kingdom and an invaluable insight into many aspects of daily life in medieval England, is today kept in the UK National Archives, London. It remains one of William's greatest achievements.

Death & Legacy

Fortunately for William, the Danish invasion never materialised. Canute IV of Denmark (r. 1080-1086), who was planning the escapade, was murdered as part of a rebellion that was fuelled by the king's imposition of taxes and fines to pay for his invasion fleet and army. Then, out of the blue, disaster struck while William was attacking the town of Mantes in retaliation for its raids on Normandy. On 9 September 1087, William died from illness, perhaps from an injury riding his horse and exacerbated by the obesity that afflicted him in later life. He was buried in St. Stephen's monastery in Caen, which he himself had built, although the funeral had its problems: a fire in neighbouring houses interrupted the procession, a man shouted out during the ceremony that the cathedral had been built on his father's lands without any compensation, and the sarcophagus was so small that when they tried to push the corpulent corpse in the stomach burst and filled the cathedral with a noxious smell.

According to one medieval manuscript, the king's epitaph went as follows:

Who governed the proud Normans, by his firm hand

constrained the Bretons vanquished by his arms;

The warriors of Maine he curbed by valour,

Kept in obedience to his rule and right.

The great king lies here in this little urn,

So small a house serves for a mighty lord.

(De obitu Willelmi, Allen Brown, 49)

The anti-Norman Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (entry for 1087) gives the following, perhaps more balanced summary of William's reign:

This king William of whom we speak was a very wise man, and very powerful and more worshipful and stronger than any predecessor of his had been. He was gentle to the good men who loved God, and stern beyond all measure to those people who resisted his will.

(quoted in Allen Brown, 79)

After William's death, his English kingdom was taken over by his son William II Rufus (r. 1087-1100). Meanwhile, William's other son, Robert Curthose, took over the family lands in Normandy. Both rulers would struggle to keep their respective domains from usurpers and ambitious nobles. England and Normandy would only be ruled again by a single monarch from 1106, six years into the reign of Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135), another son of William the Conqueror.

William the Conqueror, then, lived an eventful life of more or less non-stop warfare and travel between England and northern France. It is perhaps the subsequent interlocking history of these two countries where we see William's greatest legacy, for good and bad. By joining the two together, mixing the ruling elites and greatly increasing trade, the political and cultural repercussions of William's conquest of England would be felt for centuries to come.