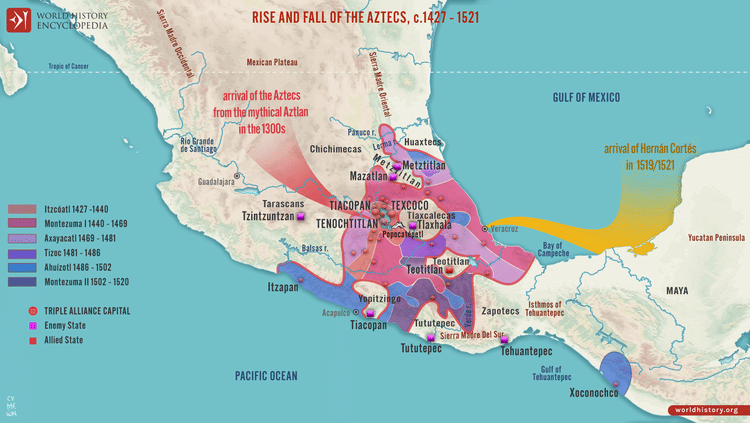

Tenochtitlan (also spelled Tenochtitlán), located on an island near the western shore of Lake Texcoco in central Mexico, was the capital city and religious centre of the Aztec civilization. The traditional founding date of the city was 1345 CE and it remained the most important Aztec centre until its destruction at the hands of the conquering Spanish led by Hernán Cortés in 1521 CE, which led to the final collapse of the Aztec Empire. At the heart of the city was a large sacred precinct dominated by the huge pyramid, known as the Temple Mayor, which honoured the gods Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. The site, now Mexico City, continues to be excavated and has yielded some of the greatest treasures of Aztec art such as the celebrated Sun Stone as well as art objects the Aztecs themselves collected from the other great civilizations of Mesoamerica.

In Mythology

In Aztec mythology the founders of the city migrated from the legendary Aztlán cave in the northwest desert which involved a protracted journey that eventually led to Lake Texcoco. During this migration priests had carried a huge idol of the god Huitzilopochtli, who whispered directions, gave the Méxica their name and promised great wealth and prosperity if he was suitably worshipped. Along the way the Méxica settled at different spots, none of which really suited their purpose. A decisive event in the migration was the rebellion incited by Copil, son of Huitzilopochtli's sister Malinalxochitl. This was in revenge for the goddess' abandonment by the Méxica but with Huitzilopochtli's help Copil was killed. The great war god instructed that the rebel's heart be thrown as far as possible into Lake Texcoco and where it landed would indicate the place the Méxica should build their new home, the precise spot being marked by an eagle sitting on a prickly-pear cactus (nopal) and devouring a snake. This is exactly what came to pass and the new capital of Tenochtitlan was built, the traditional date being 1345 CE.

The name of the city derives from tetl meaning rock, nochtli, the prickly-pear cactus and tlan, the locative suffix. Of similar origin is the term Tenocha which the Méxica sometimes called themselves and the name of their quasi-legendary priest-leader Tenoch.

The City

Although the city was destroyed and over the following centuries extensively built over, the chroniclers of the 16th century CE, fortunately, recorded in great detail the buildings and works of art that had once made Tenochtitlan one of the greatest cities in Mesoamerica and, with over 200,000 residents, certainly the most populous. These records and the extensive and continuing archaeology at the site mean that we know more about Tenochtitlan than any other city from the great Mesoamerican civilizations.

As Bernal Diaz del Castillo, one of Cortés' men put it on first seeing the city:

It was like the enchantments in the book of Amadis, because of high towers, rues [pyramids] and other buildings, all of masonry, which rose from the water. Some of the soldiers asked if what they saw was not a dream.

(Miller, 239)

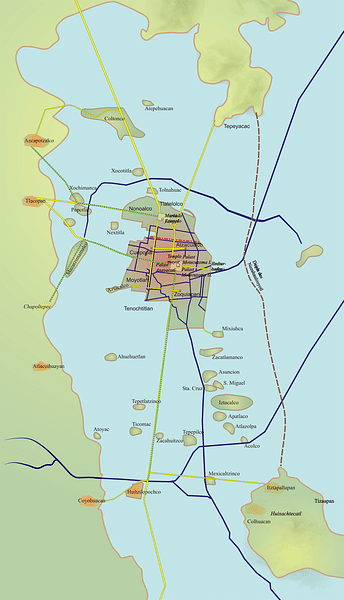

Tenochtitlan covered, at its greatest extent, some 12-14 km² and was connected to the western shore of the lake and surrounding countryside by three causeways (running north, east and west) which included gaps traversed by removable bridges to allow boats to pass and which could be taken down in case of an attack on the city (something which never occurred until the Spanish arrived). There was also a stone aqueduct which brought fresh water to the city from springs near the Chapultepec Hill. The lake provided an important source of food but good agricultural land was scarce and this fact would necessitate re-claiming land from the lake and, eventually, military conquest to take land by force from neighbouring states. The surrounding chinampa or 'floating gardens' (mud rafts secured with willow trees) of their immediate neighbours were, therefore, seized and developed to meet the needs of the growing population in the city.

The city itself was laid out in a grid pattern with many canals permeating through the city. Besides the four main thoroughfares dissecting the city along the cardinal directions, most streets and canals were narrow, especially as there were no wheeled vehicles or beasts of burden so that goods were transported by porter or small boats and canoes. The canals, along with the many willow trees, flower gardens and white-plastered monuments gleaming in the sunlight, must have made for a picturesque city. As one Nahuatl poem describes:

The city is spread out in circles of jade,

radiating flashes of light like quetzal plumes,

Besides it the lords are borne in boats:

over them extends flowery mist.

(Coe, 192)

The heart of the city was the walled ceremonial precinct with its three entrances, impressive temples and pyramids from which the city spread out into four principal residential quarters. These had sometimes vast palaces such as Motecuhzoma I's old residence and the palace of Axayacatl, smaller flat-roofed stone residences for nobles and officials, huge market places (where all manner of basic and luxury goods could be purchased such as jade, chocolate and vanilla), judicial chambers, treasure houses, store-rooms, structures such as the Dance House and the Aviary, and closely packed areas of workshops (working especially metal and obsidian but also basketry using the local reeds) and small adobe brick and reed homes where the lower classes lived, although these too could be interspersed with small gardens.

The Sacred Precinct

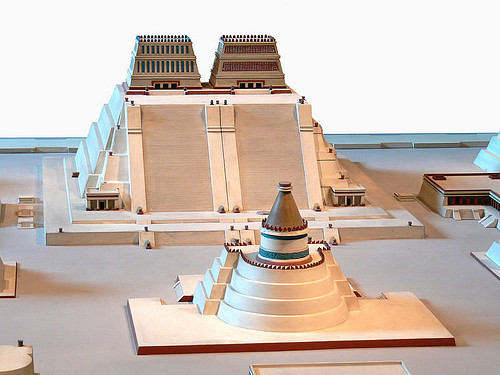

The sacred precinct at the heart of Tenochtitlan contained, according to one eye-witness, 78 separate structures. Amongst the most important were the Temple Mayor of Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli, which was flanked by the Eagle's House (named after its stone decoration) on one side and the pyramid of Tezcatlipoca on the other. In front of the Temple Mayor stood the gladiator stone (where sacrificial victims were bound and attacked by 'knights'), a stone tzompantli (skull rack) and an I-shaped ball court. In the south west corner stood the Sun Temple of Tonatiuh and a temple to Quetzalcoatl.

There was also a temple to the earth goddess Tonantzin and the Coateocalli building which housed, and in a sense spiritually captured, the statues of gods and various other artworks captured from conquered enemies. Finally, on the Tlaloc side of the Temple Mayor excavations have revealed a man-made mountain made of offerings and deposits which was designed to imitate Tlaloc's sacred mountain.

The Temple Mayor

The Great Temple or Temple Mayor (called Hueteocalli by the Aztecs) takes centre stage in the sacred precinct. On top of the 60 m high pyramid platform, reached by two flights of steps, were two twin temples. The north side shrine was dedicated to Tlaloc, the god of rain and the other, on the south side, was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war. The temple to Tlaloc marked the summer solstice (symbolic of the wet season) whilst Huitzilopochtli's marked the winter solstice (symbolic of the dry season and a time for warfare). The monumental steps leading to Tlaloc's temple were painted blue and white, the former colour representing water, the element so strongly associated with the god. In contrast, the steps leading to Huitzilopochtli's temple were painted bright red to symbolise blood and war.

Sacrifices, including human ones, were carried out at both temples to feed and honour the gods. A typical sacrifice involved the victim having their heart ripped out, being skinned, decapitated and then dismembered. Following all that the corpse was flung down the steps of the pyramid to land at the base where a massive round stone depicted Coyolxauhqui, the goddess who was similarly treated by Huitzilopochtli in mythology.

Destruction

When the Spanish arrived at Tenochtitlan, their leader Cortés had only 500 men and fewer than 20 horses at his disposal. However, by recruiting allies such as the Tlaxcalans, he was able to lay siege to the city which would eventually fall on the 13th of August 1521 CE. The great monuments were sacked and looted, works of art and precious objects were melted down and the Aztec civilization collapsed. What was left of the city was made into the capital of New Spain, as the Spanish called their new colony.

Archaeology

Excavations within the temples and buildings of Tenochtitlan began in the 20th century CE and have revealed the true complexity of the site's history. There is evidence, for example, that the sacred precinct was built over much earlier structures, that the temples themselves were reconstructed and added to many times and within them were buried offerings, for example, the coral, shells and sea-life interred deep within the Temple Mayor.

The city was stripped of anything of value following its collapse but, nevertheless, several stunning works of art have been, almost miraculously, recovered from Tenochtitlan. These include the iconic Sun Stone (aka Calendar Stone), the great stone sculpture of Coatlicue, the Tizoc stone, the huge round stone depicting Coyolxauhqui which rested at the foot of the Temple Mayor, the Temple Stone - a stone throne probably used by Motecuhzoma II and decorated with gods and a sun disk, and finally, the blue ceramic anthropomorphic vessel depicting Tlaloc.

In addition to these magnificent works of Aztec art, excavation of the temples has revealed caches of art from many earlier Mesoamerican civilizations as far back as the Olmecs, illustrating that the Aztecs were appreciative and even reverent art collectors. Many richly decorated and finely made ceramic vessels have also been excavated which show that the Aztec artist was perhaps more skilled than had first been appreciated. The vast majority of these finds form part of the breathtaking collection of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, which has been, of course, constructed on top of the ancient site of Tenochtitlán.