Stirling Castle, located on a strategically important rocky outcrop by the River Forth in central Scotland, was a key royal residence from the late 11th century into the early modern period and subject to many battles and sieges, particularly during Scotland’s wars of independence from England in the Late Middle Ages. Over centuries of eventful Scottish history, the castle witnessed the death of two kings and two coronations, multiple sieges and not a few murderous intrigues. The castle functioned primarily as a military base in its later history, but today it has been restored to its former glory when it was the royal residence of the Stuart monarchy at the height of its power and magnificence.

Early History

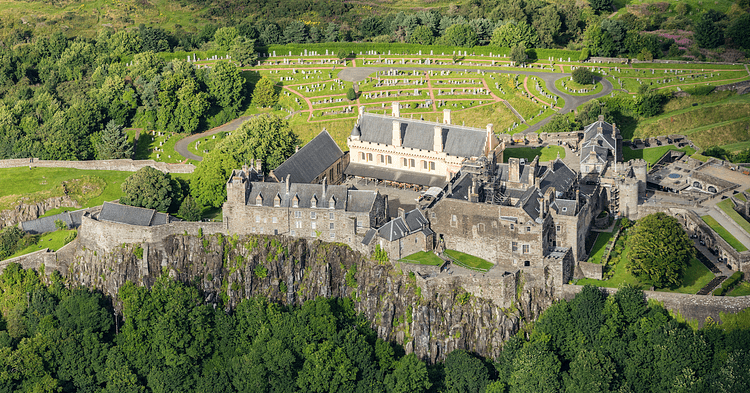

Stirling Castle occupies a strategically important point between the Scottish Lowlands and Highlands. For this reason, the castle has been described as the ‘brooch’ which joins the two halves of Scotland. Perched atop a rocky volcanic crag, the castle was able to control traffic along the River Forth below, the Stirling Bridge that crossed a low point in the river, and several roadways that passed nearby from all directions. The attractive defensive qualities of the site with its sheer cliffs on all but the southeast sides meant that it has been occupied since prehistoric times. During the Iron Age (1st-2nd century CE) there may well have been a hilltop fort on the site controlled by the Maetae or Votadini tribe.

The first known buildings at the site, likely made of timber, were built in the late 11th century during the reign of Malcolm III of Scotland (r. 1058-1093). Leaders from across Scotland met at the castle annually in this period. During the reign of Alexander I of Scotland (r. 1107-1124) and his successors, Stirling Castle developed as a major royal residence, often regarded as just as important as Edinburgh Castle. Alexander, who built a stone chapel at the site, died at the castle in 1124, as did William I of Scotland (r. 1165-1214) in 1214. Another advantage to the castle was the excellent hunting opportunities in the surrounding area. Indeed, Alexander III of Scotland (r. 1249-1286) added a hunting park to the west of the castle which was populated with deer (this park is now a golf course). The great quantities of food needed for when the royal household was in residence came from the large estates of nearby Cambuskenneth Abbey, founded c. 1140.

The Late Medieval Castle

Stirling Castle played a prominent role during the Wars of Independence when English kings tried to subdue Scotland and make it a province of their kingdom. The Scottish hero William Wallace (c. 1270-1305 CE) led a famous victory against a much larger English army near the castle at Stirling Bridge in 1297. Stirling Castle was again in Scottish hands after Wallace’s victory but was regained by the English in 1298 after victory at the battle of Falkirk. It was retaken by the Scots in 1299/1300 as the English occupying army struggled to hold on to such an isolated castle. It was in 1300, or thereabouts, when the North Gate was added, the oldest structure in the castle today (although it was adapted in 1381). An English army once again captured the castle in 1304. The siege took three months after the invaders battered the castle walls with a massive siege engine known as the War Wolf, a catapult that required 445 men to assemble.

Stirling Castle and several others were still in English hands when Robert the Bruce (r. 1306-1329) set about systematically removing the English from Scotland a decade later. It was the siege at Stirling by Bruce’s army that finally persuaded Edward II of England (r. 1302-1327) to lead an army in person to Scotland in 1314. These two forces met at Bannockburn in June and the Scots won a resounding victory. After the battle, the English garrison at Stirling Castle surrendered. Robert the Bruce, as he did at Edinburgh, then had the castle demolished lest the English ever came back and took control of it again.

Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377) recaptured and rebuilt Stirling Castle during the mid-1330s as part of his intervention in Scottish affairs when he supported the claim to the throne of Edward Balliol (c. 1283-1367) against the incumbent monarch, the young David II of Scotland (r. 1329-1371). The Scots finally got the castle back after a six-month siege in 1342.

James I of Scotland (r. 1406-1437) held a parliament at the castle and, in 1424, staged a show trial there of nobles who had been disloyal during the king’s 18-year imprisonment in England. Future James III of Scotland (r. 1460-1488) was born in Stirling Castle in May 1452, but his father James II of Scotland (r. 1437-1460) seems to have been destined to suffer unhappy occurrences at the castle such as in February 1452, when the king invited his great rival William Douglas to Stirling Castle for peace talks. Earl William was promised safe conduct but the king, suspecting him of making treasonable alliances with a number of northern barons, got into a heated argument and stabbed him in the neck; his courtiers then finished off the earl. Parliament absolved the king of any intention to kill the earl but a civil war followed anyway between the Black Douglases and those nobles loyal to King James. James won that war three years later.

In 1463 James III repaired the castle and he added a workshop for casting cannons in 1475. The castle again came to prominence with the nearby battle of Sauchieburn between James III and rebellious Scottish nobles. Occurring in June 1488 and more of a skirmish than a full-scale battle, the rebels won the encounter, killing the unpopular Stuart king in the process.

The Early Modern Castle

Stirling Castle benefitted from a great refit during the reign of James IV of Scotland (r. 1488-1513) and his immediate successors. A new Great Hall was built c. 1500 with new kitchens to serve it, the Chapel Royal was added, an inner courtyard laid out, and the general defences improved, including a massive new main gate with twin circular towers. James IV’s Great Hall, the largest ever built in Scotland, boasted five fireplaces and four spiral staircases; it was faithfully restored to its original appearance in the 1990s. This was part of the European-wide trend to make castles more comfortable residences, and it continued with additions made by James V of Scotland (1513-1542) whose coronation was held at the castle on 21 September 1513. The new king fitted out the royal apartments in the French Renaissance style in the late 1530s. These additions became known as the Palace building.

James V was succeeded by his daughter Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542-1567) whose coronation was also held in the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle on 9 September 1543. Mary held a three-day extravaganza at the castle to celebrate her son’s baptism in December 1566, an occasion which saw a mock siege of a huge model castle and the first firework display ever held in Scotland.

Henry, the eldest son of James VI of Scotland (r. 1567-1625, who became James I of England, r. 1603-1625), was born in Stirling Castle in 1594, and he spent much of his childhood there. James VI, due to his protestant beliefs, had had the Chapel Royal demolished and replaced in 1594 by a more suitable structure, and this hosted the baptism of Henry. The happy event saw a massive 40-ton model of a ship sail on an artificial lake in the Great Hall, the weight of which damaged the structure of the building.

With James VI’s coronation as the king of England in 1603 and his move to London, Stirling Castle’s days as a primary royal residence were over, but it remained an important castle, and its strategic value was not missed by commanders during subsequent wars. The 17th century witnessed extensive work on the castle’s gardens including the ornamental garden and canal known as the ‘King’s Knot’ on the south side. In 1651 the castle fell to a siege by forces loyal to Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) and led by General George Monck; the dents from cannonballs fired during this attack can still be seen today around the main gate. Around 1690, an artillery battery was added to the east side of the castle, and in 1708, new outer defences in the form of a wide dry ditch were added. The castle yet again found itself under siege during the Jacobite Rising of 1745-1746 to restore the Stuart line to the throne. A force led by Prince Charles Edward Stuart, better known as ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ (1720-1788), attempted to take the castle but were themselves blasted into submission by Stirling’s now formidable artillery defences.

The castle then functioned primarily as an army barracks from the mid-18th century until 1964. As part of this military focus, the Great Hall was converted to a three-storey barracks around 1800, the Esplanade parade ground was created on the eastern side of the rock promontory in 1809, and powder magazines were built in the nether bailey in 1810. With a purely military function, many of the residential buildings were neglected, but at least this lack of refurbishment left older structures intact, a situation which archaeologists have since found invaluable in reconstructing the evolution of the castle.

The Castle Today

The main gates to the castle on the east side are much lower than their original 16th-century version but remain impressive with their massive towers and portcullised gates. An idea of the original height of this part of the castle can be ascertained from the contemporary Prince’s Tower on the west side. The visitor passing through the gates enters the Outer Close, the first of two courtyards. Here are the Great Hall, Main Guard House, and Palace buildings. The adjacent Inner Close was the heart of the medieval castle and site of the original royal apartments (before the Palace was added); today it is enclosed by the Royal Chapel and King’s Old Building (which dates to the reign of James IV).

The Great Hall has been restored to its early 16th-century heyday - including its hammer-beam ceiling - and parts of the Palace interior have been refurbished in the style of the mid-16th century. The Palace’s inner hall, which was likely used as a royal audience chamber, contains its original fireplace and wooden door. The ceiling of this hall has replicas of the Stirling Heads, roundels which represent various members of the Stuart royal family, Roman emperors, Hercules and other figures symbolically attached to the Scottish monarchy. The original surviving heads, which date to c. 1540, are on exhibit on the upper floor of the Palace. The Queen’s Chamber has been richly decorated in the style fashionable when Mary of Guise (1515-1560), wife of James V, lived in the castle.

Today the castle is managed by Historic Scotland and hosts the regimental museum of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, located in the King’s Old Building. The upper floor of the Palace building, meanwhile, regularly hosts temporary exhibitions related to the castle’s long and illustrious history.