Edinburgh Castle, towering atop Castle Rock, has served Scotland for centuries, at one time or another acting as a fortress, royal residence, seat of government, armoury, and prison. The scene of countless sieges, royal births and deaths, murderous intrigues, and military displays, Edinburgh castle has long been a symbol of Scottish history and national pride. Today, the castle is open to the public who can see such sights as the Stone of Scone, the Scottish royal regalia known as the Honours, the National War Museum, the National War Memorial, and such famous giant medieval cannons as Mons Megs. The most popular tourist attraction in Scotland, the castle, together with the city of Edinburgh, is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Early History

Perched on a volcanic rocky outcrop with sheer cliffs on three sides, Edinburgh Castle dominates the skyline of the capital city of Scotland. Occupation of the site stretches back to the Bronze Age, and archaeological excavations have revealed the cliff top was artificially levelled c. 900 BCE. In the 1st and 2nd century CE, during the Iron Age, the site hosted a hilltop fort typical of that period. This fort was probably the capital of the Votadini tribe. The fort, mostly composed of timber and earthworks, had an entrance protected by two huge ditches. Buildings within the fort were also made of timber and many had stone floors and hearths. There is also evidence of a stone drainage system at the site. Trade between the Votadini and the Romans in southern and central Britain is evidenced by finds of imported jewellery.

The castle first appears in literature in the early 7th century CE collection of poetic verses known as The Gododdin. At this time it was the site of a fortification built by the tribe of the same name, who then controlled parts of southern Scotland and Northern England. The fort was known as Din Eidyn, a name later anglicised to Edinburgh after the Angles conquered the Gododdin and took possession of it. Continuing as a fortress into the early Middle Ages, unfortunately, no parts of the castle or fortifications prior to the 11th century CE remain, and there are only a few relics belonging to the people who once dwelt there.

The Medieval Castle

Saint Margaret of Scotland (c. 1046-1093) was, as the second wife of Malcolm III (r. 1058-1093), the queen of Scotland from 1070 until her death in November 1093. Her reign and contribution to the spread of Roman Catholicism in her kingdom were commemorated in the Norman chapel built at Edinburgh Castle, today the oldest original part of the fortress. The private chapel was most likely built around 1130 by Margaret’s son David I of Scotland (r. 1124-1153). David had embarked on a building spree of many castles in Scotland, among which was Edinburgh Castle where he likely built a Norman-style castle keep.

Despite its formidable appearance on a mighty rock and relative self-sufficiency in water, thanks to the Fore Well, the castle proved something of a disappointment when it came to sieges. Following the capture of William I of Scotland (r. 1165-1214), the English took control of the castle between 1174 and 1186. The castle was regained but, in 1296, Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307) managed to gain entry after only a three-day siege. Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray took back control of the castle from the English garrison there in 1314 during the struggle to establish the Bruces as the royal house of Scotland.

Robert the Bruce (r. 1306-1329), no doubt unimpressed with the fortresses’ record, then demolished the castle right down to its foundations in 1314, chiefly as a sure means to ensure the English never made use of it if they ever captured the rock again. An English force did indeed capture the citadel in 1335, and they began to rebuild the castle. However, a small Scottish force led by Sir William Douglas masqueraded as merchants and recaptured the castle for Scotland in 1341.

A new royal castle became the great project of Robert the Bruce’s son and successor, David II of Scotland (r. 1329-1371). David added a massive new tower, inspired perhaps by a similar new addition to Windsor Castle in England. ‘David’s Tower’, as it became known, was once 30 metres (100 ft) high and was the location of the royal chambers for a century or so after its completion in the mid-1370s CE. James I of Scotland (r. 1406-1437) added another tower just behind David’s Tower towards the end of his reign, which contained a large hall purpose-built for banquets. Ultimately, this ‘Great Chamber’ replaced the royal chambers in David’s Tower. It was either the Great Chamber of James I’s tower or the Great Hall of David’s Tower that hosted one of the castle’s most infamous episodes in 1440, the so-called 'Black Dinner'. This meal occurred when the entourage of the young James II of Scotland (r. 1437-1460 CE) hosted the two young heirs of the powerful Douglas clan. The Douglas boys were invited to dinner cordially enough but on the evening in question were presented with a bull’s head on a platter. This was a sign for the boys to be taken away and executed.

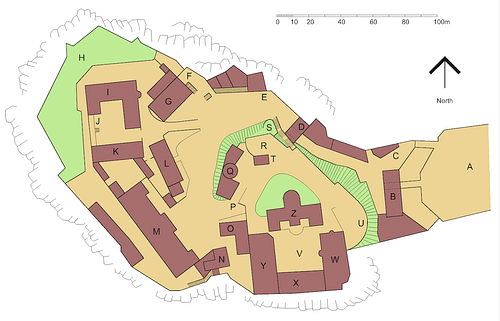

Not very much remains of any of these medieval additions to the castle and most of the buildings today date to the reign of James IV of Scotland (r. 1488-1513). David’s Tower, for example, collapsed during a siege, and its ruins are now completely covered by the Half Moon Battery. The Crown Square (formerly known as the Grand Parade and located near the former site of David’s Tower) had been created by James III of Scotland (r. 1460-1488) and does still survive as a courtyard which became the symbolic heart of the royal domestic quarters at the castle along the lines of the contemporary royal residences of continental Europe. The great medieval fortress had finally begun its transformation into a palace.

The Early Modern Castle

James IV used the castle as a royal residence, but its role as a fortress was not completely forgotten, the king utilising it as a repository of the kingdom’s artillery pieces. King James also added a new Great Hall to the castle (completed c. 1510), and this then hosted the Scottish parliament. The Great Hall endured a checkered history over the centuries, high points being its use for state banquets while low points were its use as a military barracks and then hospital in the 19th century. The ceiling seen in the hall today is the late medieval original, analysis having shown that the oak beams originally came from forests in Norway c. 1510. The Royal Palace of the Crown Square was now complete and was the location of the castle’s first and last royal birth, that of future James VI of Scotland (aka James I of England, r. 1603-1625) on 19 June 1566 CE.

The castle once again failed to hold secure during a four-day siege in 1573 when an English army with cannons bombarded the supporters of the deposed Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542-1567) into a quick submission. Following the siege, a massive semi-circular battery, the Half Moon Battery, was added to the castle’s defences on the eastern side. The Battery boasted a group of bronze cannons known as the ‘Seven Sisters’. This addition typified the castle’s primary role as a fortress, monarchs now preferring to reside instead at the more comfortable Holyroodhouse Palace, also in the capital. Edinburgh Castle was used as a residence by some state officials, and it became the home of the national archives, an arsenal, and occasional prison.

The revamped castle was indeed now more of a challenge for attackers, as shown by the lengthy sieges of 1640 during the Wars of the Covenant and in 1650 by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658). During the remainder of the 17th and right through the 18th century, the castle became a military barracks - St. Margaret’s chapel was even used to store artillery ammunition - and a camp for prisoners of war such as during the Jacobite rebellion (1745-1746) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), amongst other conflicts. Over the years, the prison’s inmates became increasingly international and ranged from pirates of the Caribbean to Americans captured during the War of Independence (1775-1783). In 1842 the Military Prison was built for disobedient soldiers from the castle’s own barracks; imaginative punishments included carrying cannonballs from one part of the prison compound to another. There was also a military hospital.

In the early decades of the 19th century, the castle benefitted from a large new parade ground, known as the Esplanade, which reformed the 1753 parade ground and covered the former site of public executions known as Castle Hill. This open space now hosts the world-famous Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo every August. Further remodelling took place, notably on the gatehouses and the Great Hall in the last quarter of the 19th century as part of a new process of rising Scottish national pride, a trend further evidenced in the construction of a Scottish National War Memorial on the rock in 1927, an appropriate enough spot considering the castle had itself been subject to a Zeppelin bombing raid during the First World War (1914-1918).

The Castle Today

Edinburgh Castle today is, with well over one million annual visitors, Scotland’s most popular tourist destination. Besides being an impressive monument in itself with every stone steeped in history, the castle is also the home of the National War Museum and three regimental museums. As part of the city of Edinburgh, the castle is designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, an honour awarded in 1995.

The castle’s main gates are on the east side, the only accessible side of the rocky plateau, and were built in 1888 to replace a much older structure. Dating to the 1570s (after the 1573 siege mentioned above), the second set of gates one walks through includes a portcullis and was once reinforced with three additional pairs of wooden doors. The top of this structure, Argyle Tower, was added in 1887. An additional inner gate is Foog’s Gate, which dates to the latter part of the 17th century CE. Just after the portcullis gate is a flight of 70 stone steps, the Lang Stairs, and these lead to the heart of the castle. A less-fatiguing route is the cobbled roadway straight ahead, built in the 17th century to allow mighty cannons to be drawn into the castle.

The Governor’s House is a 1742 building in the Georgian style and official residence of the governor who acts as the Commander of the Army in Scotland. The New Barracks, completed in 1799, functions as a military barracks and hosts the Regimental Museum of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. The nearby Drill Hall contains the Museum of the Royal Scots and the Royal Regiment of Scotland. Finally, one of the more curious corners of the castle is the dog cemetery. This was created in the 1840s and reserved for faithful four-legged companions of soldiers in the barracks and regimental mascots like Dobbler (d. 1893), who accompanied the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders to South Africa, Sri Lanka, and China during his nine years of active service.

This greatest of Scottish castles contains many historically important objects, and chief amongst these is the Stone of Scone. Also known as the Stone of Destiny, the block of sandstone was associated with the coronations of medieval Scottish kings at Scone Abbey on the island of Scone in Perthshire. Legend has it that only where the stone resides will Scottish kings rule. Removed from Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 in a deliberate act of political propaganda, the stone was finally returned to the Scottish people in 1996.

Alongside the Stone of Scone in the Crown Room of the castle are the items of the Scottish royal regalia collectively known as the Honours. These items date to the 16th century and consist of a crown, sceptre, and sword of state. They were first used together in the coronation of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1543 in Stirling Castle. Moved to various locations and then locked in a chest in a sealed room in the castle during Scotland’s troubled history with England, the Crown Jewels were rediscovered by the great novelist and historian Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) in 1818. The magnificent regalia had not been seen by anyone for over a century but was soon put on public display in the Crown Room where they remain today. Over the years, more jewels have been added to enrich the collection, and these include the Stewart Jewels with the large ruby ring said to have been worn by Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) during his coronation in Westminster Abbey.

The famous Mons Meg cannon now resides at Edinburgh Castle, an artillery piece built in the mid-15th century CE, possibly for James II of Scotland. The massive cannon weighs six tonnes and once fired cannonballs 48 cm (19 in) in diameter over a distance of 3.2 km (2 miles). Taken to the Tower of London in 1754, Mons Meg was given the honour of a full military escort and returned to Edinburgh Castle in 1829. Another cannon, more famous for its sound across the city than its appearance, is the One O’clock Gun, which is fired each day at 1 pm (except Sundays), a tradition that began in 1861 as a navigational aid to passing ships.