Squanto (l. c. 1585-1622) was the Native American of the Patuxet tribe who helped the English settlers of Plymouth Colony (later known as pilgrims) survive in their new home by teaching them how to plant crops, fish, hunt, and generally acclimate to life in the so-called New World.

He is also known as interpreter between the colonists and the Native Americans of the Wampanoag Confederacy led by the chief Ousamequin, better known by his title Sachem Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661). Squanto's real name is believed to have been Tisquantum (as he is consistently called by colonist and chronicler Edward Winslow, l. 1595-1655) while “Squanto” is a nickname given him by the second governor of Plymouth Colony, and his close friend, William Bradford (l. 1590-1657).

Squanto was kidnapped by the English captain Thomas Hunt in 1614 to be sold into slavery but either escaped or won his freedom in Spain and traveled to England where he learned English and worked as interpreter and shipbuilder. He returned to North America as interpreter on a trade mission and traveled with one Thomas Dermer back to his home village near present-day Cape Cod only to find his tribe had been wiped out by disease (probably smallpox) brought by European traders.

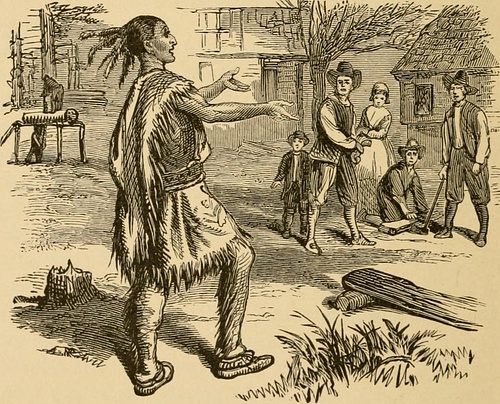

In 1621, he was introduced to the settlers at Plymouth (who had founded their colony at the site of his old seasonal village) by the Abenaki chief Samoset (also known as Somerset, l.c. 1590-1653) who also spoke English. Squanto quickly became indispensable to the colonists and, recognizing his own power, he secretly worked to undermine the authority of Massasoit and empower himself. Once discovered, Massasoit demanded he be turned over for execution, but Bradford refused, a decision which endangered the treaty between the Wampanoag Confederacy and Plymouth Colony if Massasoit had insisted or tried to take Squanto by force.

Squanto continued to serve as the colonists' guide and interpreter until 1622 when he died of fever or, as some historians have speculated, was executed by poison on orders from Massasoit. He is almost always depicted in history textbooks and children's books as “the friendly Indian” who saved the pilgrims and participated in the feast which has come to be known as the First Thanksgiving. These narratives ignore his plot against Massasoit or the circumstances surrounding how he came to learn English and, for the most part, he continues to be depicted as a one-dimensional character in the story of the pilgrims and the First Thanksgiving, although modern scholars and historians have made significant efforts to correct this image.

Tribe & Kidnapping

The name Tisquantum was possibly a title but, probably, the designation he took after attaining maturity and proving himself worthy of the respect of his tribe. Scholars are undecided on the meaning of the name but generally agree it had something to do with supernatural power and was associated with the entity known as Manitou, the “great good spirit” of the world referenced in the Algonquian language spoken by the Patuxet and other tribes ranging from present-day Canada down to Virginia.

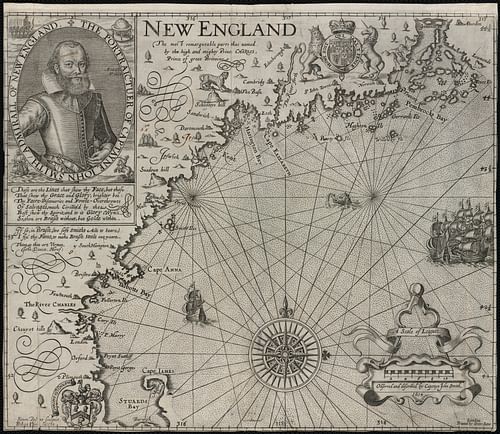

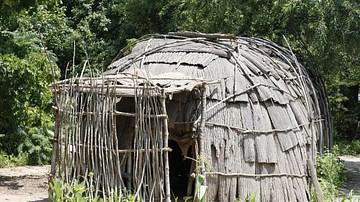

The Patuxet had lived around the area of Cape Cod for thousands of years before the arrival of the Europeans. Their main villages were inland with seasonal settlements along the coast. Beginning c. 1605, European merchants started visiting the area of New England, bringing with them diseases for which the Native Americans had no immunity. In 1614, Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) arrived and mapped the region in the company of one Thomas Hunt. Smith had experience with the natives of North America from his time at the colony of Jamestown between 1607-1609 and, having established a good relationship with the Powhatans of Virginia, sought to do the same with the natives of New England (as he called the area) so that they would be open to trade with the English.

Smith's efforts were rewarded and he left to bring his report and maps to England, leaving Hunt to complete their business and follow. Hunt decided to further enrich himself by adding human beings to his cargo and kidnapped 24 natives to sell into slavery. One of the 24 “savages” kidnapped was Squanto, and when Hunt reached Malaga and tried to sell his captives, many of them were taken – without payment – by friars in the area who condemned him for the kidnapping and freed the prisoners, taking them to their monastery to instruct them in Christianity. There are no details available concerning Squanto's time there, but at some point, he managed to escape and made his way to England.

Return to North America

In England, he worked as an interpreter and shipbuilder for the merchant John Slane who built ships for the various investment companies hoping to profit from establishing colonies in North America and India. While in England, he was acquainted with – or at least known by – John Smith who mentions him as living there and may also have met Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617) when she came there on a public relations tour with her husband John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622), the tobacco magnate of Jamestown.

By 1619, Squanto had been hired by the captain Thomas Dermer as an interpreter and was part of his expedition to Newfoundland to establish trade. In Newfoundland, Squanto convinced Dermer to sail down to the area of New England where, he said, the captain would find friendly natives of his tribe to trade with. Once they arrived, however, Squanto found that his entire village had been wiped out by disease and he was the last of his tribe (he was not, actually, as some members were later found to have left and gone to live with others of the Wampanoag Confederacy).

Those natives they did encounter, such as the Nauset and Massachusetts, were far from friendly owing to the betrayal and kidnapping by Hunt, poor treatment by others, and the European diseases which had killed so many of them. Dermer was attacked, receiving fourteen wounds, and survived until he reached Jamestown where he died. Squanto remained in New England, living among the Pokanoket tribe of Massasoit, possibly as a prisoner - owing to his association with Dermer - or at least as a guest the chief thought might be useful, if untrustworthy.

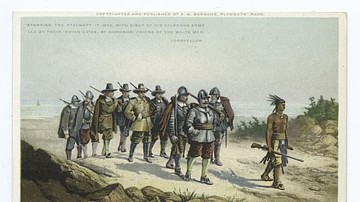

When the settlers of the Plymouth Colony arrived in November 1620, the natives of the area watched in secret to determine what they had come for and how long they might be staying. They understood that this new ship meant to settle its passengers in the region when they saw women and children arrive on the shore to wash clothes. Throughout the winter of 1620-1621, 50% of the passengers and crew died from disease, malnutrition, or exposure and the settlers were still struggling to survive in the spring when Massasoit decided to send an envoy to test the immigrants' intentions.

The plague of the past few years had greatly reduced the population of the Wampanoag Confederacy which had been dominant in the region beforehand and received tribute from all the neighboring tribes. By 1620, they were so reduced that other tribes – such as the Narragansett and Massachusetts – were powerful enough to demand tribute from them. Massasoit thought it could be beneficial to align himself with this new group of English who might help him regain his former status. He, therefore, sent a visiting Abenaki sachem, Samoset (also possibly a prisoner of Massasoit), who had learned English from various traders, to find out what the immigrants wanted and whether they were friendly.

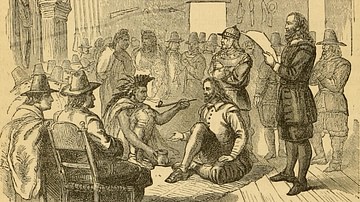

Samoset returned with the news that he had been welcomed at the settlement, given food and drink and lodging for the night, and that he felt the settlers could be of use to Massasoit. Massasoit then sent Samoset back with Squanto, following with some of his warriors close behind. Samoset introduced Squanto who then introduced Massasoit and his braves. After gifts were exchanged, Squanto served as interpreter as a peace treaty was drawn up and signed, promising mutual support and respect between the colonists and the Wampanoag Confederacy. Afterwards, Massasoit told Squanto to remain at the village and help the settlers in any way he could.

Savior of the Pilgrims & First Thanksgiving

The traditional view of Massasoit, Squanto, and Samoset as encouraged by United States' textbooks and various literary works since the 19th century, has been of the “noble savage” who decided to assist the struggling pilgrims out of the goodness of their hearts and were later thanked by an invitation to a harvest feast, which became known as the First Thanksgiving. In reality, each of the three had their own motives for engaging with the colonists.

Samoset was doing a favor for Massasoit but, having dealt with Europeans before, would have wanted to learn first-hand what these new arrivals meant for the future of his people and himself. Conversely, if Samoset was Massasoit's prisoner (as claimed by the colonist Thomas Morton, l. c. 1579-1647), he was sent not only because he spoke English but because he was expendable. Massasoit was looking to forge an alliance, and Squanto, initially anyway, was acting on Massasoit's orders.

After the treaty was signed, Massasoit and Samoset returned to their village, known to the colonists as Sowams, 40 miles (64 km) away from Plymouth but, as Bradford relates in Of Plymouth Plantation,

Squanto stayed with them [the colonists] and was their interpreter and became a special instrument sent of God for their good, beyond their expectation. He showed them how to plant their corn, where to take fish and other commodities, and guided them to unknown places, and never left them till he died. (Book II. ch. 1)

The settlement flourished with Squanto's help as he not only taught them how to farm, fish, and hunt but acted as interpreter in trade agreements which gave the colonists a monopoly on the fur trade in the region. Throughout 1621, Squanto proved indispensable to the colony, but there is no evidence in the primary documents that he or any of the Native Americans were invited to a harvest feast that fall to thank them for their help.

Bradford, in Of Plymouth Plantation, only notes that they had recovered their health and were “plentifully provisioned” with “every family having their portion” at the time of the harvest (Book II. ch. 2) while the narrative from Mourt's Relation – the first-hand account written by Bradford and Winslow – gives the more detailed narrative which is so often reprinted as the story of the First Thanksgiving:

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors. They four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king, Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain [Myles Standish] and others. (82)

There is nothing to suggest that an invitation was sent to Massasoit or any others but there is mention of the colonists firing off their weapons (“we exercised our arms”) followed by the detail that Massasoit and 90 of his warriors then came amongst them. Bradford and Winslow both note that the natives would come frequently to the settlement after the treaty was signed in order to trade, and it is likely that Massasoit and his men were on just such a mission.

It is also likely that, hearing the weapons fired, Massasoit hurried to the village to see if the colonists needed help as per the terms of the treaty. Squanto was most likely at the feast, as he had been stationed with the pilgrims, and another warrior – Massasoit's right-hand man – Hobbamock (d. c. 1643) would also have been present as he and his family had also come to live among the colonists.

Conflict & Death

Hobbamock, like Massasoit, did not trust Squanto because the latter had lived among the immigrants in their own country, knew their language well, and since no one else did, there was no way of knowing whether Squanto was interpreting honestly. As it turned out, Hobbamock's fears were justified as Squanto had been pursuing his own interests among the various tribes of the Wampanoag Confederacy in an attempt to undermine Massasoit's authority and take his place as chief.

He told his fellow natives that the colonists had the plague stored in barrels beneath their homes and could release it upon anyone they pleased at will. For a price, Squanto told them, he could buy favor with the strangers and offer protection, and in this way, he received significant wealth in gifts and established himself as a power in the region. Squanto was “the tongue of the English” and claimed he alone had the authority to keep the people safe from the wrath of the English and their god or encourage them to release the plague and kill everyone.

Hobbamock first caught on to Squanto's scheme when he overheard him telling others about the barrels hidden beneath the colonists' homes and, instead of questioning him, went and asked Bradford and the others. They explained the barrels contained foodstuffs, and it was not them but the will of God that brought or protected them from the plague. Squanto's full plan finally came to light when he orchestrated an elaborate hoax designed to have the colonists attack Massasoit.

In early summer of 1622, the colonists had been told that the Massachusetts were planning to attack a newly settled colony at Wessagussett and would then wipe out Plymouth to prevent retaliation. Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656) was sent by Bradford to deal with the problem but, on arriving, found no evidence of any planned attack. Even so, he killed a number of natives in a preemptive strike. Knowing this, Squanto agreed to serve as guide on a trade mission which included Standish, leaving Plymouth without its military commander and interpreter, in the hope that Bradford would follow the same pattern and strike at Massasoit without much provocation.

Shortly after they left, a native arrived at the colony, bleeding from his head, claiming that Massasoit was coming to attack Plymouth and how he had been wounded standing up for the colony as he was related to Squanto and knew he was their friend. Bradford ordered the cannon to be fired, hoping Standish was still within earshot, and the party returned. Hobbamock told them there was no way Massasoit was planning any attack since, as his second-in-command, he would have been told of it, and his wife was then sent to Massasoit's village to see if there was any preparation for war. She reported back that there was none, nor did Massasoit seem to have any ill will toward the colony.

According to both Bradford and Winslow, Squanto was “sharply reproved” by Bradford, but when Massasoit heard of it and demanded Squanto be handed over to him for execution, Bradford refused, rightly claiming that Squanto was too valuable to them to be given up. Later, while on a trade mission with Bradford, Squanto developed a nosebleed which he claimed signaled his impending death. Bradford stayed by his side as he requested prayers that he go to the Christian god's heaven and gave away his personal possessions and then died, according to Bradford, of “Indian fever”. It has been speculated, however, that he may have been poisoned by agents of Massasoit who resorted to this method of eliminating his enemy to avoid conflict with Bradford.

Conclusion

Aside from the primary sources by Bradford and Winslow, Squanto is rarely mentioned in early works on the Plymouth Colony and only begins appearing in later narratives after the success of the 1855 poem The Song of Hiawatha by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (l. 1807-1882) who also popularized the pilgrims' story in his The Courtship of Miles Standish in 1858. Squanto does not appear in Hiawatha but the concept of the “noble savage” is central and seems to have been applied to Squanto after 1863 when Thanksgiving was declared a national holiday in the United States and the tale of the First Thanksgiving began to be reprinted annually.

Actually, Squanto was no more or less “noble” or “savage” than any of the colonists at Plymouth or any of the Wampanoag Confederacy. The natives of North America were far from the naïve and innocent nature-lovers or ignorant brutes later English narratives depict them as. They were as well acquainted with political intrigue as the Europeans; they simply conducted those intrigues differently.

Squanto is only known through the accounts of Bradford and Winslow which can only provide accounts of what happened, not why it happened. It is probable, however, that Squanto, having lost everything he had known to the diseases brought by the immigrants and forced to live as essentially a servant to Massasoit, saw an opportunity to gain something back for himself and seized it, a view of the man which Bradford himself suggests and far more realistic and understandable than the traditional view of Squanto as the helpful and noble savage.