Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617, also known as Amonute, Matoaka) was the daughter of Wahunsenacah (l. c. 1547 - c. 1618, also known as Chief Powhatan), leader of the Powhatan Confederacy in the region of modern-day Virginia, United States. She was a citizen of the Mattaponi-Pamunkey Nation who were members of the confederacy.

She is best known today for her association with Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) of the Jamestown Colony of Virginia, a relationship frequently characterized as a love affair (as in the famous Disney animated feature film and video sequel) although Pocahontas would have been, at most, 12 years old and Smith around 27 at the time of their meeting. The story of her saving Smith’s life after he was captured and brought to her village is now understood as either Smith’s misinterpretation of a Powhatan ritual or a complete fabrication.

Jamestown was established by the English in 1607, and Pocahontas would have met Smith sometime that year. He returned to England in 1609, and shortly afterwards relations between the Powhatan Confederacy and the colonists deteriorated. Pocahontas was kidnapped by Sir Samuel Argall (l. c. 1580-1626) in 1613 and held for ransom at the colony of Henricus, north of Jamestown, where she converted to Christianity and changed her name to Rebecca. She met the wealthy tobacco merchant John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622) at Henricus whom she married in 1614. Their marriage ended the First Powhatan War (1610-1614) and established an eight-year peace between the indigenous people and the immigrants.

The couple had one son, Thomas Rolfe (l. 1615 - c. 1680), and went on a trip to England, promoting Jamestown and further colonization, in 1616. As they began their journey back, Pocahontas fell ill and died in March 1617. Thomas was left with relatives, and John Rolfe returned to Virginia, dying in 1622, probably in the outbreak of the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626). Pocahontas is often depicted as an 'Indian Princess', as she was known during her time in England, who preferred life among the English to her own people.

Modern scholarship, however, has highlighted the fact that the best-known version of her story comes from English sources, which made the most of her conversion and marriage as propaganda to encourage further colonization of North America. The Mattaponi oral tradition provides a different version of her life in which she remains closely aligned with the traditional values of her people, was never a princess, and was victimized by Rolfe and others in his circle. The events of her life, and their meaning, continue to be debated.

Early Life & Jamestown

Pocahontas' birth name is said to have been Amonute (meaning disputed, possibly 'gift') but later took (or was given) the name Matoaka ('flower between two streams'). 'Pocahontas' was her childhood nickname usually translated as 'playful one' and was possibly the name of her mother. Although she is routinely referenced as the daughter of Wahunsenacah, this may have been an epithet since, as Chief Powhatan, he was regarded as the 'father' of those under his care. It is possible, therefore, that the English colonists – notably John Smith – understood 'daughter' literally when it was not.

Almost nothing is known of her mother. If one accepts that Pocahontas was the actual daughter of Wahunsenacah, then she would have been taken back to her mother’s village after birth to be cared for until she was weaned at which time she would have been sent to her father. It has been suggested that her mother died in childbirth and she was raised by one of Wahunsenacah’s other wives in his village. She was a citizen of the Mattaponi Nation, a branch of the Pamunkey, and spoke Algonquian, as did the others in the confederation.

She would have been brought up to learn the traditional tasks and responsibilities of women in the Powhatan Confederacy such as building a house (known as a yehakin), planting and harvesting crops, cooking meals, weaving mats and baskets, foraging for herbs and plants, and managing financial transactions. As the daughter of the chief (and, according to John Smith, his favorite), she may have been given added responsibilities or could have been relieved of some of the more tedious but, whichever, greater care would have gone into watching over and protecting her.

When the English colonists established Jamestown in 1607, Chief Powhatan warily accepted them, even welcoming them, as he thought they might become allies against the Spanish who had raided the coastal regions in the past. John Smith suggests that the 10-year-old Pocahontas was sent as an intermediary with only one or two escorts but this, like many of Smith’s claims, has been challenged as she would have been better protected. Contact was made between the two peoples sometime in the early summer of 1607, and Wahunsenacah provided the newcomers with food and assistance in establishing themselves.

Pocahontas & John Smith

Pocahontas first met John Smith when she was sent to Jamestown to negotiate the return of some captives who had been detained for allegedly stealing tools and weapons. Smith claims she arrived in the company of the warrior Rawhunt, a trusted companion of the chief, and describes her as "a child of ten years old, which not only for feature, countenance, and proportion, much exceedeth any of the rest of his [the chief’s] people" (Smith, 34). The business was concluded, and Smith gave Pocahontas "such trifles as contented her" and asked her to relay to her father how well the captives had been treated. Afterwards, allegedly, Pocahontas traveled to the settlement or met with Smith and they taught each other their respective cultures and languages, but this claim has been challenged.

In December 1607, Smith was apprehended by Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646), Wahunsenacah’s half-brother. Smith describes the event in a 1608 account and relates how he was taken to a number of villages before he was presented to Wahunsenacah at the capital of Werowocomoco and treated as an honored guest. Wahunsenacah was able to make Smith understand he wanted an alliance, that Smith was not a captive, and he was later allowed to return to Jamestown.

In 1616, when Pocahontas arrived in England, a celebrity and the wife of the wealthy John Rolfe, Smith told another version of this event in a letter to Queen Anne of Denmark (l. 1574-1619, wife of James I of England). In his updated version, he is roughly used by Opchanacanough and ordered to be executed by Wahunsenacah. Smith is thrown onto a rock and a Powhatan warrior raises a club to kill him when Pocahontas intervenes, laying her head on his, and demanding his release. He repeated this version, with further embellishment, in his 1624 work, The General History of Virginia.

Although this story is central to the standard Pocahontas tale, scholars agree that it either never happened or that the entire event was misinterpreted by Smith. If it happened at all, it was most likely a ritual through which Smith was being welcomed to the tribe through a death-and-rebirth ritual in which he faced mortality, was saved by Pocahontas playing a role, and reborn as 'Chief of the Settlers' – exactly the sort of title Wahunsenacah had in mind for him as ally. Many scholars, however, claim the event could never have happened because girls – especially those as young as Pocahontas – were not allowed to take part in or witness such rituals.

The Powhatan continued their relationship with Smith, sometimes more contentious than others, for two years until, wounded in a gunpowder explosion, he returned to England. By this time, relations between the two peoples had soured because the colonists, ill-suited for the task of settlement in a foreign land, continually asked the Powhatans for food and supplies instead of providing for themselves. Smith never told Wahunsenacah or Pocahontas that he was leaving for England; a slight she would remind him of years later in England.

Rolfe’s Arrival & Kidnapping

Smith’s leadership of the colony may have been imperfect, but he had kept the colonists fed, and without him, they starved through the winter of 1609-1610. The supply ship, the Sea Venture, which should have arrived from England in 1609, was shipwrecked off Bermuda that summer (later becoming the inspiration for William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest), and it took the passengers and crew almost a year to build two new ships there to bring them to Jamestown in May 1610. Onboard one of the ships was the new colonial governor, Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622) and John Rolfe.

Gates found the colony in a state of ruin, with only 60 colonists left alive. He ordered the colony abandoned, loaded the survivors on board, and was heading downriver when he was met by the ship of Thomas West, Lord De la Warr (l. 1577-1618) who ordered them about and took control of reestablishing the colony. Rolfe either arrived with, or somehow got hold of, some seeds for the plant Nicotiana tabacum – the sweet tobacco plant whose seeds were carefully guarded by the Spanish who had made a fortune from the crop – and began to cultivate tobacco. By 1611, he had his first crop, and by 1614, he was a wealthy man.

According to the Mattaponi version of events, Rolfe received the seeds from the Powhatan as well as the knowledge of how to cultivate, harvest, dry, and process the tobacco that made him rich. Tobacco use was well-known among the indigenous people as a sacred plant used in religious rituals, for communal gatherings, to seal treaties, and as a stimulant and medicinal herb. If Rolfe did receive such instruction and his original seeds from the Powhatan, he never mentioned it to anyone else. The source of Rolfe’s seeds is still debated in the present day.

The continual neediness of the colonists, coupled with De La Warr’s harsh policy toward the natives, led to the First Powhatan War in 1610. This conflict moved back and forth across the Virginia tidewater favoring now one and then the other side. In the meantime, Pocahontas had grown up and, according to the Mattaponi, married a warrior named Kocoum, possibly one of her father’s bodyguards, and went to live as a citizen of his Nation, the Patawomeck, in a village nearer to Jamestown.

By 1613, Sir Samuel Argall (l. c. 1580-1626) had taken over from De La Warr (who had returned to England) and maintained his predecessor’s policies toward the Powhatan. He heard that Pocahontas was nearby in the Patawomeck village and kidnapped her in 1613, killing Kocoum. The details of how this was accomplished are debated, but the colonists now had an important captive they held for ransom, demanding the return of prisoners, weapons, and supplies from the Powhatan. Wahunsenacah complied with the demands, but Pocahontas was not freed. Instead, she was told her father did not care for her and would not pay the ransom. Pocahontas only learned the truth when her sister was allowed to visit her and contradicted the colonists’ story.

Marriage & Conversion

The details of Pocahontas’ captivity are also debated. According to the Mattaponi version, she was treated poorly, raped, and became pregnant; Rolfe only married her to keep news of the rapes from reaching her father which would have led to greater conflict which was bad for his business. The colonist Ralph Hamor (l. 1589-1626), however, claims she was treated well and given every courtesy in the home where she stayed in the colony of Henricus, north of Jamestown. Across the river from Henricus was the plantation of John Rolfe, and he met Pocahontas when he visited the settlement.

Scholars who challenge the Mattaponi version of events point to a letter Rolfe wrote to then-governor Sir Thomas Dale (l. c. 1560-1619) asking for permission to marry Pocahontas and how it would help the community at large, noting that her conversion to Christianity would inspire other natives to do the same. If she had actually been abused and Rolfe had only married her for pragmatic reasons, the argument goes, why would he have bothered to write such a sincere letter?

Rolfe and Pocahontas were married on 5 April 1614 at Jamestown, the service presided over by the Anglican priest Richard Buck who had arrived with Rolfe. Their union ended the First Powhatan War and established the Peace of Pocahontas which would last until 1622. Pocahontas had converted to Christianity following her acceptance of Rolfe’s proposal and chose Rebecca as her baptismal name. In January 1615, their son Thomas was born and, according to Ralph Hamor, life for both the natives and the immigrants had improved dramatically since the wedding and relations were profitable for both.

England Tour & Death

In 1616, the Rolfes were invited to travel to England by the Virginia Company, who had funded the 1607 expedition to establish Jamestown, on a promotional tour for the colony. The investors who had financed the expedition had finally seen a return through Rolfe’s very profitable crop, and it was thought he could persuade others to invest. Pocahontas (now Rebecca Rolfe), a native turned 'cultivated lady', would allay the English fears that Native Americans were "dangerous, soulless savages" who could not be civilized.

Wahunsenacah sent along his sage (and Pocahontas' brother-in-law) Tomocomo with other members of her family, and the party landed in England in June 1616. Pocahontas was an instant celebrity at the English court and events staged in her honor. She was escorted around London by aristocrats such as Lord De La Warr and his wife, met Queen Anne and King James I, and was lavishly entertained. She even sat for her portrait to be painted and an engraving was made of her to commemorate her visit. John Smith avoided meeting with her until she was about to leave, and when they met again, she criticized him harshly for failing to honor the agreements he had made with her father. She further informed him how they had been told he was dead and how this only further confirmed how little the English could be trusted.

According to some sources, Pocahontas wanted to remain in England, but this claim is challenged. Rolfe had to return to Virginia, and the party left in March 1617. They had not even left the Thames River when Pocahontas fell ill and died shortly afterwards. She was buried at Gravesend 21 March 1617. Her cause of death is usually given as something like pneumonia or tuberculosis, but it has also been suggested she was poisoned, possibly with Rolfe’s consent or participation, to keep her from telling her father certain intelligence she had learned in England. This claim is challenged, however, citing the presence of Tomocomo and others who would have had the same, or similar, experiences as Pocahontas and continued on their way without mishap.

Conclusion

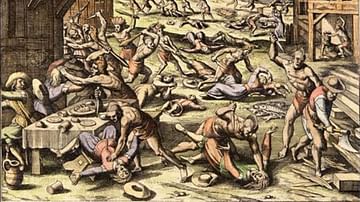

Thomas Rolfe had become ill at the same time as his mother and was left in the care of someone at Gravesend until he could be retrieved by Rolfe’s brother. Rolfe returned to Virginia, married his third wife in 1619, and died in 1622, probably in the Indian Massacre of 1622 which started the Second Powhatan War. Upon their return from England, Tomocomo had denounced the English to his chief, and even though colonial writers claim that Tomocomo’s charges were completely discredited by colonists and he was shamed into silence, the war launched by Opchanacanough in 1622 suggests that Tomocomo’s account was taken seriously. What exactly the sage charged the English with is not known, but the Powhatans led by Opchanacanough after Wahunsenacah stepped down hardly needed any more reason for war than the many broken agreements and the expansion of the English colonies at the expense of the indigenous people.

Thomas Rolfe grew up in England and returned to Virginia to claim his father’s land c. 1635. He was respected by the Powhatans as the son of Pocahontas but seems to have been regarded with some suspicion by his fellow English. He fought for the colonists in the Third Powhatan War (1644-1646) as a lieutenant in the militia and was rewarded with significant land grants afterwards for his service, clearly suggesting he fought against his mother’s people, though this claim, like many aspects of Pocahontas’ life, is challenged as he may have held a defensive position but not engaged in combat.

Over the past 400 years, she has been characterized as a traitor to her people who sided with the English, as a spy for the Powhatans, as a victim of brutality and rape, and as a sincere convert to Christianity who enjoyed life among the English. Pocahontas, like many of the most resonant historical figures, reflects the values of each individual who comes in contact with her, and it should be remembered that what one receives from that experience is a reflection of one’s own story, not necessarily hers.