The Sacred Band of Thebes was an elite unit of the Theban army comprised of 150 gay male couples totaling 300 men. They were formed under the leadership of Gorgidas but first achieved fame under the general Pelopidas. They remained invincible from 378-338 BCE when the entire troop fell together at the Battle of Chaeronea.

The military unit is first mentioned in 324 BCE in the speech Against Demosthenes by the orator Dinarchus (l. c. 361 - c. 291 BCE), but their full story is given by Plutarch (l. c. 45/50-c. 120/125 CE) in his Life of Pelopidas. Plutarch is thought to have drawn heavily on two earlier historians, Callisthenes and Ephorus, contemporaries of the band, whose works are now lost. The Sacred Band were deployed early in the Boeotian War in 378 BCE under Gorgidas but became famous for their participation in the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE. They remained undefeated until the decisive battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE when the Macedonians under Philip II (r. 359-336 BCE) and his son Alexander (the Great, r. 336-323 BCE) crushed the combined forces of Thebes and Athens.

The Sacred Band fell together as a single unit and, according to Plutarch, were mourned by Philip II of Macedon himself as valiant warriors. They later became legendary figures exemplifying courage and military strength. Dinarchus’ speech references them and Pelopidas (l. c. 410-364 BCE) as embodying the values he claims Athens has lost and should work to regain.

The once-famous troop of heroes is often passed over in discussions of Greek history because they were gay and the concept of a victorious unit of gay warriors is at odds with the prevalent homophobia of the present day. As LGBTQ+ activism makes more progress in educating people, however, the Sacred Band of Thebes is again receiving the kind of recognition they deserve.

Background & Possible Platonic Influence

There seems to have been some troop of elite warriors in Thebes, numbering 300, prior to the formation of the Sacred Band who are referenced by Greek historians Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE) and Thucydides (l. c. 460/455-399/398 BCE), but the famous group was formed after 379 BCE when Pelopidas and other pro-democracy Theban exiles in Athens overthrew the Spartan oligarchy that had taken control of the citadel of Thebes in 382 BCE. Once the Spartans were driven from Thebes Gorgidas organized (or reformed) the Sacred Band.

Scholars continue to debate whether the troop was created in response to Plato’s famous passage concerning an army of pairs of lovers in his dialogue of the Symposium. Plato’s work is usually dated to c. 385 BCE and, if that date is correct, it may have influenced Gorgidas. In Symposium, the character Phaedrus claims that a troop of male lovers could conquer the world:

Numerous are the witnesses who acknowledge Love to be the eldest of the gods. And not only is he the eldest, he is also the source of the greatest benefits to us. For I know not any greater blessing to a young man who is beginning life than a virtuous lover or to the lover than a beloved youth. For the principle which ought to be the guide of men who would nobly live at principle, I say, neither kindred, nor honor, nor wealth, nor any other motive is able to implant so well as love. Of what am I speaking? Of the sense of honor and dishonor, without which neither states nor individuals ever do any good or great work. And I say that a lover who is detected in doing any dishonorable act or submitting through cowardice when any dishonor is done to him by another, will be more pained at being detected by his beloved than at being seen by his father, or by his companions, or by anyone else. The beloved too, when he is found in any disgraceful situation, has the same feeling about his lover. And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best governors of their own city, abstaining from all dishonor, and emulating one another in honor; and when fighting at each other’s side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world. For what lover would not choose rather to be seen by all mankind than by his beloved, either when abandoning his post or throwing away his arms. He would be ready to die a thousand deaths rather than endure this. Or who would desert his beloved or fail him in the hour of danger? The verist coward would become an inspired hero, equal to the bravest, at such a time; Love would inspire him. That courage which, as Homer says, the god breathes into the souls of some heroes, Love of his own nature infuses into the lover. Love will make men dare to die for their beloved-love alone; and women as well as men. (178d-179b)

The dramatic date of Symposium, the setting of the story, is 416 BCE. If an army of lovers existed before the Sacred Band, then Plato may have been referencing them, but it does not seem the earlier unit referenced by Herodotus and others fits Phaedrus’ suggestion as there is no mention of that group being exclusively gay. Scholars also continue to debate what role, if any, Xenophon’s Symposium had on the creation of the Sacred Band, but that work’s date of composition is generally held to be c. 360 BCE, after the troop had already distinguished itself at Leuctra.

It is entirely possible there was an earlier unit of exclusively gay lovers, however, and the Sacred Band was simply the most famous grouping. Scholar Louis Crompton comments:

In classical Greece, not only Athens but cities with every kind of constitution took notice of the fact of male love. Aristocracies where the privileged few held sway recognized its power to forge bonds between promising youths and conservative mentors. Democracies saw it as insurance against tyranny. Tyrants sometimes forbade it…But the major source of its prestige remained its contribution to military morale. In the fourth century this heroic tradition found its most famous embodiment in the so-called hieros lochos, the Sacred Band of Thebes…Its success was to make Thebes for a generation the most powerful state in Greece, and its fate was in the end the fate of Greece itself. (69)

The kind of same-sex relationship both Plato and Crompton are referencing is the Greek model of male love in which a lover (the erastes) nurtured the growth and cultivation of the beloved (the eromenos), a younger man. The paradigm was considered an important aspect of the agoge, the Spartan education program, which produced their great warriors, and as Crompton notes, its value in morale was also recognized by other Greek city-states.

Formation & First Action

There is no information on why the Sacred Band was formed when it was, but it is thought it was in response to the kind of Spartan aggression that had taken control of Thebes, as well as other city-states, c. 382 BCE. Plutarch gives the most complete account of its creation and personnel:

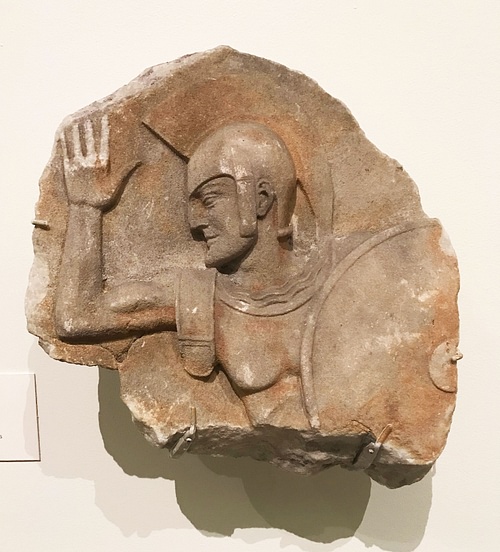

The sacred band, we are told, was first formed by Gorgidas, of three hundred chosen men, to whom the city furnished exercise and maintenance, and who encamped in the Cadmeia [citadel]; for which reason, too, they were called the city band; for citadels in those days were properly called cities. But some say that this band was composed of lovers and beloved. And a pleasantry of Pammenes is cited, in which he said that Homer’s Nestor was no tactician when he urged the Greeks to form in companies by clans and tribes, "that clan might give assistance unto clan, and tribes unto tribes" since he should have stationed lover by beloved. For tribesmen and clansmen make little account of tribesmen and clansmen in times of danger; whereas a band that is held together by the friendship between lovers is indissoluble and not to be broken, since the lovers are ashamed to play the coward before their beloved, and the beloved before their lovers, and both stand firm in danger to protect each other. Nor is this a wonder, since men have more regard for their lovers even when absent than for others who are present, as was true of him who, when his enemy was about to slay him where he lay, earnestly besought him to run his sword through his breast, "in order", as he said, "that my beloved may not have to blush at sight of my body with a wound in the back." It is related, too, that Iolaus, who shared the labors of Heracles and fought by his side, was beloved of him. And Aristotle says that even down to his day the tomb of Iolaus was a place where lovers and beloved plighted mutual faith. It was natural, then, that the band should also be called sacred, because even Plato calls the lover a friend "inspired of God". It is said, moreover, that the band was never beaten, until the Battle of Chaeronea. (18.1-5)

Gorgidas chose the 300 hand-picked men for their skill and reputation as warriors, without regard to their social class, and first led them in battle during the Boeotian War (378-371 BCE) which broke out shortly after Pelopidas and his colleagues reclaimed Thebes from Sparta. Their first engagement was against the Spartan army under king Agesilaus II (r. c. 400-360 BCE) in 378 BCE under the command of Gorgidas. The Theban army and their Athenian allies were outnumbered and, as the Spartans advanced, the Athenian general Chabrias (d. 357 BCE) ordered his men to stand down and assume the "at ease" position of the raised spear and shield held down at knee level. Gorgidas followed suit with his command and Agesilaus II, disconcerted by their obvious confidence, called off his assault and withdrew.

Battle of Tegyra

In the engagement with Agesilaus II, Plutarch notes:

Gorgidas, by distributing this sacred band among the front ranks of the whole phalanx of men-at-arms, made the high excellence of the men inconspicuous, and did not direct their strength upon a common object, since it was dissipated and blended with that of a large body of inferior troops. (19.3)

It is thought he chose this tactic so that the Sacred Band would inspire the others with their courage and skill. Gorgidas disappears from the historical record c. 375 BCE and may have been killed at the outset of the Battle of Tegyra or just before. Either way, in 375 BCE, Pelopidas was in command of the troop and, as Plutarch notes, "never afterwards divided or scattered them but treating them as a unit, put them into the forefront of the greatest conflicts" (19.3). He first used this tactic at Tegyra and found it extremely effective.

The Thebans had learned that the Spartans left the city of Orchomenus and Pelopidas hurried to take and fortify it before they returned. On the way, they met the Spartan force coming back and, according to Plutarch, one of Pelopidas’ advance scouts ran back to him and said, "We have fallen into our enemies’ hands!" to which Pelopidas replied, "Why any more than they into ours?" (17.1). He placed the Sacred Band as the vanguard and arranged a cavalry assault. The Spartans outnumbered the Thebans and both armies charged at the same time, but the Sacred Band broke the Spartan lines, and the Theban cavalry inflicted further casualties.

The Spartans lost a number of their commanders and, now in disarray, pulled back and opened an aisle through their ranks, standing down, offering the Thebans a chance to leave the field with honor. Pelopidas ordered his men into this avenue but, instead of advancing through and escaping, they fell on the Spartans to either side, scattering them and winning the day. Plutarch writes that the Thebans then "retired homeward in high spirits. For in all their wars with Greeks and Barbarians, as it would seem, never before had [the Spartans] in superior numbers been overpowered by a [smaller] force nor, indeed, in a pitched battle where the forces were evenly matched" (17.5). The Sacred Band had established their reputation as the greatest warriors in the Theban army and, in defeating the formidable Spartans, in all of Greece, and this reputation was enhanced by their actions at Leuctra.

Battle of Leuctra

Pelopidas had long been friends with the philosopher-general Epaminondas (l. c. 420-362 BCE) and, in fact, their relationship is noted by historians for their deep bond because, unlike other generals who competed with each other for greater fame and glory, these two supported and helped one another. After Tegyra, Thebes’ power and reach increased, and in an effort to stop their further rise, Sparta urged them to accept terms of peace or face an invasion led by their king Cleombrotus I (r. 380-371 BCE). Epaminondas refused their terms and the two armies met on a plain near the village of Leuctra.

The Thebans were again outnumbered, but Epaminondas expertly arrayed his forces, concentrating on his left wing to counter the expected Spartan tactic of swinging with their right wing to flank an opponent. The battle began with a cavalry charge launched by both sides at once, but the Theban cavalry broke the Spartan cavalry’s formation and drove them back where, in their flight, they broke the lines of the infantry. Epaminondas then ordered his hoplite phalanx on the left to move obliquely and his forces on his right to shift left so that, instead of a straightforward charge, the army advanced diagonally toward the right wing of the Spartans. Before Cleombrotus I could react, Pelopidas led the Sacred Band in a double-time charge into the right wing and Epaminondas’ phalanx arrived to press and break the lines already in disarray. Plutarch writes:

The phalanx of Epaminondas bore down upon [the right wing] alone and neglected the rest of their force, and since Pelopidas engaged them with incredible speed and boldness, their courage and skill were so confounded that there was a flight and slaughter of the Spartans such as had never before been seen. (23.4)

The Theban victory broke Spartan power and, afterwards, Epaminondas marched into the Peloponnesus, liberating cities from Spartan rule. He refused to follow the model set earlier by Athens and then Sparta of subjecting the Greek city-states to Theban domination and so, as Crompton notes, "he won a unique fame as a liberator rather than an exploiter" (71). Pelopidas pursued this same course, marching on Thessaly to free the region from the tyranny of Alexander of Pheras but was killed in battle in 364 BCE. Epaminondas continued his war with the Spartans and again led his army to victory at the Battle of Mantinea in 362 BCE although he did not survive it himself.

Battle of Chaeronea

The Greek city-states were, by this time, weakened by years of warfare and were easy prey for Philip II of Macedon to the north. Philip II had spent three years as a hostage in Thebes when he was young, beginning around 367 BCE, and had watched the successes of the Sacred Band and noted Epaminondas’ clever use of the phalanx. When Philip II came to power, Macedon was militarily weak, and he used the Sacred Band as his model to strengthen it. He took the concept of the phalanx and improved upon it by replacing the spear with the sarissa, a longer pike with greater reach, and also reequipped his soldiers with better swords, armor, and helmets. The Macedonian army was, essentially, the Sacred Band on a much larger scale.

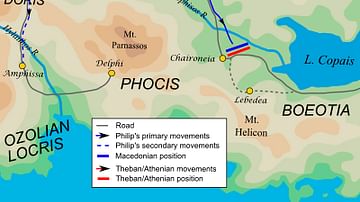

After Philip II had taken most of Greece either through diplomacy or military action, Athens allied with Thebes to halt his progress and the two armies met at Chaeronea. The Athenian-Theban coalition was vastly outnumbered as they had only around 10,000 infantry and 600 cavalry compared with the Macedonian’s 30,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. The Sacred Band was placed on the right wing facing the inexperienced, 18-year-old Macedonian prince, Alexander. The Athenians charged first, and Philip II gave ground, drawing them further into his lines, and then struck back quickly with his Macedonian phalanx, breaking the Athenian forces at the center. Alexander charged the Sacred Band on the right, as the Athenian-Theban center was falling, and surrounded them.

The Sacred Band was at this time under the command of one Theagenes, about whom nothing else is known, and held their ground against Alexander’s attack. They refused to surrender and continued fighting until the last of them fell. Plutarch writes:

And when, after the battle, Philip was surveying the dead, and stopped at the place where the three hundred were lying, all where they had faced the long spears of his phalanx, with their armor, and mingled one with another, he was amazed, and on learning that this was the band of lovers and beloved, burst into tears and said: "Perish miserably they who think that these men did or suffered aught disgraceful." (18.19)

The Sacred Band was buried on the battlefield and, later, the monument known as the Lion of Chaeronea was erected over their mass grave. Excavations of the site in the 19th century uncovered the skeletons of 254 men laid out in seven rows which have been identified as the remains of the Sacred Band. The Battle of Chaeronea gave Greece to Philip II and the Sacred Band was never reformed. Their legacy lived on, however, as the model for the army of Alexander the Great which went on to topple the Persian Empire and nearly conquer the world.