The agoge was the ancient Spartan education program, which trained male youths in the art of war. The word means "raising" in the sense of raising livestock from youth toward a specific purpose. The program was first instituted by the lawgiver Lycurgus (l. 9th century BCE) and was integral to Sparta’s military strength and political power.

Participation by Spartan males in the agoge (pronounced ah-go-GAY in ancient Greek and ah-GOJ-uh in modern English) was mandatory. Spartan girls were not allowed to join but were educated at home by their mothers or trainers. Boys entered the agoge at the age of 7 and graduated around the age of 30 at which time they were allowed to marry and start a family.

The goal of the agoge was the transformation of boys into Spartan soldiers whose loyalty was to the state and their brothers-in-arms, not their families. Literacy was included in the curriculum but was not as important as military training and survival skills. As in other Greek city-states, homoerotic relationships between older candidates and younger were considered a natural aspect of growth and maturity but, in Sparta, seem to have been encouraged to create a tighter bond between the men who would eventually serve in the armed forces.

The agoge was at its height during the Classical Period (5th-4th centuries BCE) and was praised as the ideal form of education by the philosophers Plato (l. 428/427-348/347 BCE) and Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) as well as the writer Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE). Later historians, such as Plutarch (l. c. 45/50 - c. 120/125 CE) were more critical of the program. The agoge gradually declined in support from the 4th century BCE, though some form of it existed during the early years of the Roman Empire. The precise date of the end of the agoge is unknown, but it did not survive the 396 CE sack of Sparta by Alaric I (r. 394-410 CE) of the Visigoths.

Sparta & Lycurgus

The Spartans settled the area of the Peloponnese in the valley of Laconia at some point in the 10th century BCE, and later displacing an indigenous people – the perioikoi and the helots – who were then subjugated. According to legend, Sparta’s ruling house c. 9th century BCE was divided by distrust and scheming, and the people lacked strong role models in government. Lycurgus was a Spartan prince whose older brother had died, leaving behind a pregnant wife. Lycurgus was next in line for the throne but abdicated in favor of his brother’s infant son and, to avoid any suspicion that he might harm the child to win back power, left Sparta.

He is said to have traveled first to Crete, then through Asia Minor, to Egypt, and many other places studying their laws and reflecting on the best aspects of society. After a number of years, he was contacted by the Spartans asking him to return home. His nephew, Charilaus, was evidently not the best man for the position of king and there seems to have been some significant social unrest. Lycurgus returned with a new concept of law, one that people would learn by living it and would not need a written form, and gradually won the upper class over to his vision.

Lycurgus’ reforms were comprehensive, including every aspect of the people’s lives, and, as he had mandated from the start, were not committed to writing; the laws would be kept in the people’s hearts because they would know these precepts led to the best possible society. Among his reforms was the creation of formal education and military training that became the agoge. Scholar Paul Cartledge describes the agoge as a "system of education, training, and socialization [that] turned boys into fighting men whose reputation for discipline, courage, and skill was unsurpassed" (32). Lycurgus may have been a mythological figure (his dates are given as anywhere between the 9th and 6th century BCE), but whether he was history of myth, the program he is credited with establishing became the foundation of Spartan society and military might.

Agoge Initiation: Paides

When Spartan children were born, the male elders of the family decided if the infant was fit to live and be raised. According to some accounts, one test was to drop the baby into a vat of wine and, if it cried, it was considered too weak, but this may be apocryphal. Male children were raised primarily by their fathers until the age of seven when they entered the agoge and were known as paides (boys). Cartledge comments:

Between the ages of seven and eighteen, the boys and youths were organized in 'packs' and 'herds' and placed under the supervision of young adult Spartans. They were encouraged to break the exclusive ties with their own natal families and to consider all Spartans of their father’s age to be [their parents]. (69)

For the first five years in the agoge, between the age of 7-12, boys were taught to read and write, but the program’s emphasis was on endurance events, athletic competitions, military prowess, and teaching them to survive and outwit others. Plutarch writes:

Of reading and writing, they learned only enough to serve their turn; all the rest of their training was calculated to make them obey commands well, endure hardships, and conquer in battle. Therefore, as they grew in age, their bodily exercise was increased; their heads were close-clipped, and they were accustomed to going barefoot, and to playing for the most part without clothes. (16.6)

During this period, the child soldiers were also taught to steal, especially to steal food, as they were fed little. If they were successful, even if the theft was detected afterward and the culprit clearly suspected, no punishment was given; if they were caught, they were severely beaten. Plutarch notes:

The boys make such a serious matter of their stealing, that one of them, as the story goes, who was carrying under his cloak a young fox he had stolen, suffered the animal to tear out his bowels with teeth and claws, and died rather than have his theft detected. And even this story gains credence from what their youths now endure, many of whom I have seen expiring under the lash at the altar of Artemis Orthia. (18.1)

Stealing was considered an important survival skill and so it was not the act of theft that was punished, it was the carelessness exhibited in getting caught. In the initiate stage, the focus of the program was on instilling essential skills which would enable one not only to survive but conquer. The boys had to literally make their own beds – as in construct them – from rough reeds that grew by the river they had to break by hand without using a knife.

Any action or routine behavior considered a waste of time was discouraged, and this applied even to the way one spoke. The modern-day term laconic, meaning to express much in few words, comes from Laconia, the home of the Spartans. Youths were taught to compress their speech to give maximum meaning and power in as few words as possible. The most famous example of this is the tale of Philip II of Macedon sending the threat, “If I enter Laconia with my army successfully, I will raze Sparta to the ground” to which the Spartans replied, “If”.

Agoge Transition: Paidiskoi

Training in speech continued in the transitional period when one became known as a paidiskoi (bigger boy) around the age of twelve. Plutarch writes:

When the boys reached this age, they were favored with the society of lovers from among the reputable young men. The elderly men also kept close watch of them, coming more frequently to their places of exercises, and observing their contests of strength and wit, not cursorily, but with the idea that they were all in a sense the fathers and tutors and governors of all the boys. In this way, at every fitting time and in every place, the boy who went wrong had someone to admonish and chastise him. (17.1)

Plutarch equates the relationship of the young lovers with the classical model of other Greek city-states in which an older male (the erastes, “lover”) encourages and nurtures a younger man (the eromenos, “beloved”). In the context of the agoge program, it is thought this sort of relationship also deepened the bonds between the younger and older students who thought of themselves and were considered by others all sons of the same father, the state. Cartledge comments:

One particularly striking instance of this displaced or surrogate fathering was the institution of ritualized pederasty. After the age of twelve, every Spartan teenager was expected to receive a young adult warrior as his lover – the technical Spartan term for the active senior partner was 'inspirer', while the junior partner was known as the 'hearer'. The relationship was probably sexual, but sex was by no means the only or even always the major object. (69)

Xenophon, however, denies there was any sexual element to the relationships of the boys in the agoge. Although an Athenian, Xenophon was a friend of Sparta and, in fact, served the state as a mercenary. His two sons were both educated in the agoge program, and he maintains that there was no homoerotic element to the relationships at all. In his The Polity of the Athenians and the Lacedemonians, he writes:

The relationship of lover and beloved [in the agoge] is like that of parent and child or brother and brother where carnal appetite is in abeyance. That this, however, which is the fact, should be scarcely credited in some quarters does not surprise me, seeing that in many states the laws do not oppose the desires in question. (2.13-14)

In other words, because other city-states considered a sexual relationship between older and younger men natural, they ascribed the same to Sparta, but Xenophon claims the Spartan model differed from others. Earlier, in the same passage, he notes that Lycurgus created a system with his agoge unlike any others and only encouraged relationships that enriched the soul, not those which fed the appetites of the body.

The problem with Xenophon’s claim, however, is that the relationship between lover and beloved – anywhere - was intended to enrich the soul, and relationships which were pursued purely for sexual gratification were disapproved of in Greece generally, so Sparta would not have been an exceptional case. It is possible, therefore, that Xenophon is wrong even though he is frequently cited by modern writers claiming there were no homoerotic relationships among the candidates of the agoge.

Agoge Maturity: Hebontes

After the transitional stage, students were known as hebontes (young men) and were under the tutelage of a paidonomos (boy-herder). Plutarch writes:

Under [the direction of the paidonomos] the boys, in their several companies, put themselves under the command of the most prudent and warlike of the so-called Eirens. This was the name given to those who had been for two years out of the class of boys, and Melleirens, or would-be-eirens, was the name for the oldest of the boys. This eiren then, a youth of twenty years, commands his subordinates in their mock battles, and indoors makes them serve him at his meals. He commissions the larger ones to fetch wood, and the smaller ones potherbs. And they steal what they fetch, some of them entering the gardens, and others creeping right slyly and cautiously into the public messes of the men; but if a boy is caught stealing, he is soundly flogged as a careless and unskillful thief. (17.2-3)

The paidonomos was appointed by the city’s Ephors (overseers), who were elected officials sworn to uphold the laws of Sparta and were even given authority to challenge a sitting king if he did not do the same. The Ephors were among the older men who oversaw punishments given to the younger boys by their elders. They would not intervene while the punishment was inflicted, but afterwards they would judge whether it was excessive or too lenient. The paidonomos would learn from the Ephors what constituted excess or leniency and was often the overseer of punishments.

It seems probable that the boys all ate together throughout the agoge, but at the age of maturity one needed to be elected to a certain mess also known as a "common tent" (a suskania). There were many different dining messes, and it was imperative that a young man be elected to one of them. Cartledge notes:

Election was competitive; a single “no” vote was enough to get a candidate rejected. Some messes were of course more exclusive and desirable than others, none more so than the royal mess, in which both kings dined jointly with their chosen aides when in Sparta. Failure to secure election to any mess at all was tantamount to exclusion from the Spartan citizen body and, perhaps, also army. (71)

Once election to a mess was secured, all the men of that mess ate every meal together. The only excuses for non-attendance were participation in a religious ritual or a hunting expedition. Whether they were in Sparta or deployed elsewhere, every man of that mess was required to bring food to be shared in common and so, obviously, had to be present. The main meal was held after dark and no torches were allowed for lighting the way to or from the mess hall in order to encourage the men’s skill in navigating terrain in the dark and, so, the enable them to gather and eat when in the field without alerting an opposing force to their location.

During this final period of the agoge, a man might marry but most did not until they graduated at the age of 30. Once married, they could start a family but still were expected to eat with their mess. The women of Sparta also ate communally, just apart from the men. Women had their own sphere of influence and power but were not allowed to participate in any aspect of Greek warfare. To the Spartans, women had the most important responsibility of all: giving birth to warriors.

Conclusion

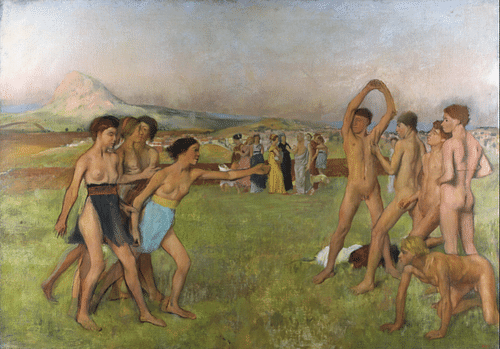

Healthy daughters were also a priority, however, as they would eventually be expected to produce children of their own. While the boys were going through the agoge program, the girls were raised by their mothers or by trusted servants but, unlike in other city-states such as Athens, they did not learn how to spin, weave, or clean house. Spartan girls participated in the same physical fitness routines as the boys when young, even training with them at first, and were then educated in reading, writing, and mousike ("music") a term which included singing, dance, playing a musical instrument, and composing poetry. Spartan girls also engaged in a number of sports including boxing, wrestling, discus and javelin toss, horseback riding, and foot races. They had no need to learn to sew or weave because the menial jobs in Sparta were taken care of by the helots.

Although a Spartan woman did not have much to do with the day-to-day raising of their sons, boys were still expected to recognize and honor their mothers through displays of courage, skill, and military victory. Plutarch and other ancient historians report Spartan mothers killing their adult sons who had run from battle or in any way displayed signs of cowardice. Thinking of one’s self and what one wanted was considered not only selfish and weak but treason in that one had put one’s own desire above the good of the state. Plutarch writes:

The training of the Spartans lasted into the years of full maturity. No man was allowed to live as he pleased, but in their city, as in a military encampment, they always had a prescribed regimen and employment in public service, considering that they belonged entirely to their country and not to themselves, watching over the boys, if no other duty was laid upon them, and either teaching them some useful thing, or learning it themselves from their elders. (24.1)

The understanding that one’s life was not one’s own to do with as one pleased but belonged to the state which had given that life was inculcated for women through the examples of their mothers and their tutelage and, for men, through the Spartan training program of the agoge. The agoge of the Classical Period continued producing its elite warriors up through 371 BCE when Sparta was defeated by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra and still continued on in some form until 396 CE when Sparta was sacked and fell to the Visigoth king Alaric. The legacy of the program lives on, however, in the reputation of the Spartan warrior as a member of the greatest fighting force of ancient Greece who, for a time anyway, seemed invincible.