The Orontid Dynasty (aka Eruandid or Yervanduni) succeeded the Kingdom of Urartu in ancient Armenia and ruled from the 6th to 3rd century BCE. Initially, the Orontids ruled as Persian satraps and the culture, language and political practices of that state were introduced into ancient Armenia. Then, under Seleucid rule, the Orontid kings became more independent and minted their own coinage. The dynasty ended around 200 BCE with the murder of Orontes IV and the appointment of king Artaxias I by the Seleucid king Antiochus III.

The Fall of Urartu

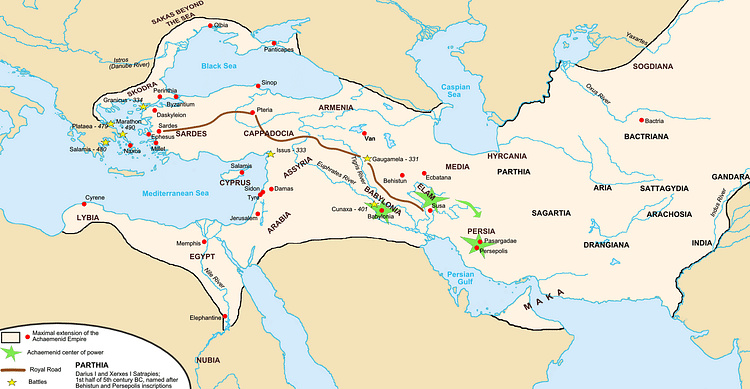

The founder of the royal dynasty of the Orontids was Orontes (Yervand) Sakavakyats (c. 570-560 BCE, although reign dates for most of the Orontids are disputed) who took advantage of the power vacuum caused by the collapse of the Urartu civilization in the last decade of the 6th century BCE. Urartu was a confederation of kingdoms which had ruled over ancient Armenia, eastern Turkey, and western Iran since the 9th century BCE. Its cities were attacked and destroyed over a decade or so by various peoples, notably the Scythians. The former territory of Urartu was then taken over by the Medes from c. 585 BCE and then incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE) in the mid-6th century BCE. The Achaemenians divided their new territory into two parts, and it was in the eastern province that the Orontid dynasty, known locally as the Yervand (from the Iranian word arvand, meaning “mighty”), ruled as satraps on behalf of their Persian overlords.

The old Urartian capital of Van, near the lake of the same name, was also the first capital of the Orontids. Orontes and his successors ruled over a disparate population of various ethnic groups, as here explained by the historian R. G. Hovannisian:

The Armenian plateau at the time of its conquest by the Achaemenian kings of Iran in the second half of the 6th century BC was inhabited by a mixture of peoples, probably with a predominance of Urarteans and Armenians, whose appellations were used interchangeably at Behistun to identify the country. It is likely, though, that the Armenian-speakers developed the strongest dynastic and cultural ties to the Iranians, becoming thereby the dominant population to which the other ethnic groups were gradually assimilated…But it would seem that some greater diversity persisted on the plateau. A few tantalising monuments, in addition to persistent proper names, may indicate that Hittite and ancient Semitic culture survived. (34)

Persia & the Orontid Satraps

The Orontids soon became ambitious to rule entirely free from Persian oversight and while the Achaemenids were distracted by the succession of Darius I (r. 522-486 BCE) they seceded from the Empire in 522 BCE. Naturally, the Persians were not best pleased at these developments and so set about reconquering the province, which was accomplished within a year, albeit taking five battles to restore order. It is then that we have the first known mention of the Persian client state of Armena or Armenia. Recorded in a c. 520 BCE inscription of Darius on a rock face in Behistun, Persia, it lists the king's royal possessions in Old Persian.

The Royal Highway connected southern Armenia to the Persian capitals of Susa and Persepolis and ran on westwards to Sardis in Asia Minor. The province of Armena was a valued source of horses and pack animals with the annual tribute consisting of some 20,000 colts along with the more convertible 400 talents of silver. Men and weapons were another form of tribute and Armenians fought in Persian campaigns as far as Greece and Egypt.

This period of the region's history is, unfortunately, lacking detailed sources and information - the inscriptions of Assyria and Babylonia, so useful for our knowledge of the Urartu civilization, now fall silent, as does archaeology, and there begins what R. G. Hovannisian describes as “a long period of darkness” (38). However, certain conclusions can be tentatively drawn from those facts we do know, as here explained by R. P. Adalian:

Few records of this period of Armenian history survive. This very scarcity is the evidence of a style of government that relied on tradition and conventions that did not require announcement and amplification. In this respect, it was a period of little innovation and possibly of considerable stability. The Persian Empire effectively protected Armenia from external conflict. Moreover, the level of tribute extracted appears to have been tolerable, for the country continued on a course of economic development, which may have lacked the intensity of the Urartian management, but whose progress was measurable by the sizeable contingents the Armenians provided the imperial army. (14)

In 401 BCE the Greek general Xenophon marched through Armenia on his way to Mesopotamia. Xenophon then records in his Anabasis that the land abounds in agricultural produce and the then Orontid ruler of Armenia was the son-in-law of the Persian king Artaxerxes I (r. 464-424 BCE), illustrating the close relations between the two regions in terms of culture (e.g. official language, Zoroastrian religion, crafts and clothing), politics, and dynastic families. By the mid-4th century BCE, the two divided regions under Persian control had been politically merged, their populations had mixed, and the language had become one: Armenian.

The Macedonians

At the 333 BCE Battle of Issus between Alexander the Great and Darius III, an Armenian contingent of 40,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry fought on the losing side of Persia. Under their king Yervand, the Armenians would also support Persia in the Battle of Gaugamela two years later, but with the same final outcome as the Persians were unable to stop Alexander's relentless march eastwards. Armenia was then formally annexed by Macedon, and in 330 BCE Armavir was made the capital (the former Urartian city of Argishtihinili). It seems likely that the political rule of Armenia remained much as under the Persians, though, with the Orontids ruling as semi-independent kings within the now vast Macedonian Empire. Indeed, even the Armenian rulers struggled to control the powerful local lords, known as nacharars and forming a hereditary nobility, such was the “feudal” nature of the region at this time.

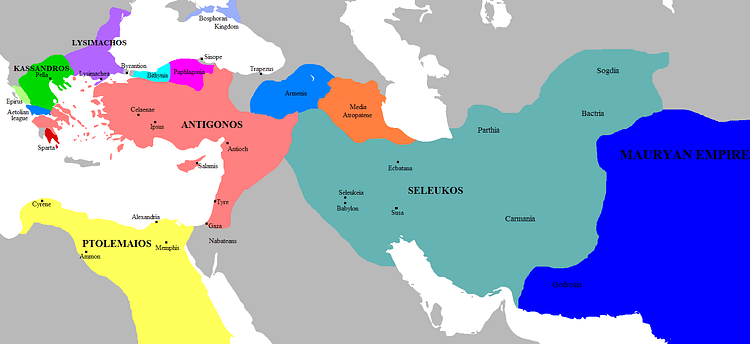

The Seleucid Empire

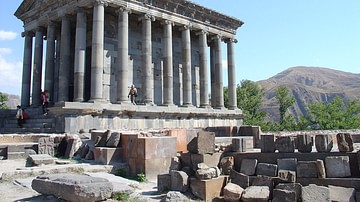

From 321 BCE the Seleucids governed the Asian portion of Alexander's empire after the young leader's death, leading to a certain Hellenization which created a rich cultural mix of Armenian, Persian, and Greek elements. Such was the size of the Seleucid Empire that the Orontid rulers were left to enjoy a good deal of autonomy in what was now a region with three distinct areas: Lesser Armenia (to the northwest, near the Black Sea), Greater Armenia (the traditional heartland of the Armenian people) and Sophene (aka Dsopk, in the southwest).

Around 260 BCE the newly unified kingdom of Commagene and Sophene arose in western Armenia, governed by Sames (aka Samos), a ruler of Orontid descent. It was Sames (r. c. 260-240 BCE) who founded the important city of Samosata (Shamshat). The period also saw the resurgence of the Persians and the growth of the Parthian Empire (247 BCE - 224 CE), who claimed sovereignty over Armenia. Sames' successor was Arsames (Arsham), who founded Arsamosata (Arshamshat) and Arsameia, both on the Nymphaios River. His independence from the Seleucid Empire is illustrated by the minting of coinage in his own name and awarding himself the title of king. The Orontids were finally catching up with the progress made in the surrounding states after decades of exposure to Greek cultural ideas, which included language, coinage, and new cities with vibrant economies which carried the name of their founders.

Armenia still, though, remained under nominal Seleucid control with the Orontids continuing as the vassal's ruling dynasty. Horses continued to be a valuable asset, Antiochus III (r. 222-187 BCE) notably reinforcing the tribute system which seems to have lapsed and extracting both 300 talents of silver and 1,000 of the animals for his armies as they passed through the region on their way to suppress the Parthians.

Demise

The last of the Orontid dynasty to rule in eastern Armenia was King Orontes IV (to the Armenians, Yervand IV or Yervand the Last, r. c. 212-200 BCE). Yervand, another ruler who gave himself the title of king, moved the capital from Armavir to the newly founded Yervandashat, meaning “Yervand's Joy”. Yervand IV's successor, following the king's murder, was the founder of the next dynasty to dominate Armenia in the coming centuries, King Artaxias I (Artashes). Artaxias, significantly, was backed and made a direct satrap by Antiochus III, probably in a move to reduce Armenian independence from Seleucid overrule. The Artaxiad dynasty (aka Artashesian dynasty), with its capital at Artaxata (Artashat) would throw off Seleucid suzerainty and rule Armenia until the first decade of the 1st century CE.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.