The Kingdom of Commagene (163 BCE - 72 CE) was a Hellenistic political entity, heavily influenced by Armenian and ancient Persian culture and traditions, established in southwestern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) by Ptolemaeus of Commagene (r. 163-130 BCE) of the Orontid Dynasty who had formerly been satrap (governor) of the region under the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE). The Seleucid Empire had been in steady decline since it came into conflict with Rome in 190 BCE and, by 163 BCE, no longer had the strength to maintain its earlier cohesion. Ptolemaeus seized on the weakness, declared Commagene an independent state, and became its first king.

The name derives from Kummuh, a Neo-Hittite kingdom of the Iron Age located in the same area, and Commagene would retain indigenous Luwian and Hittite traditions and motifs in its architecture. The region had been part of Urartu, the proto-Armenian kingdom, under the name Sophene, which became part of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE). The Achaemenid Empire fell to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE and, after Alexander's death, the region became part of the Seleucid Empire at which point Sophene became its own kingdom.

The Orontid Dynasty ruled Sophene, and Commagene was only one small kingdom among many in that region until Ptolemaeus broke away in 163 BCE. Commagene was bordered on the east by the Euphrates River and on the west by the Taurus Mountains and so became a thoroughfare for trade and enriched by its control over merchants' access to the crossings of the Euphrates to and from Mesopotamia.

Commagene is commonly referred to as a “buffer state” between the greater powers of Armenia, Parthia, Pontus, and Rome as it maintained friendly relations with all four, favoring one over the others at different times. Its wealth, from trade and agriculture, would have made it an attractive prize for any of the larger powers of the region but the kings of Commagene managed to maintain its autonomy until 72 CE when it was absorbed into the Roman Empire. It is best known for the building projects of its fourth king, Antiochus I Theos (r. 70-38 BCE), especially the monumental statuary of the site known as Nemrut Dag (also Nemrut Dagi) at Mount Nemrut.

Early History & Empires

As part of Urartu, the larger region around the future-Commagene was known as Sophene, named for the indigenous people of the area, while the actual area which would encompass the future-Commagene was known as Kummuh by the Luwians and Hittites who lived there or by the Assyrian designation, Kuinukh; nothing is known of its history at this time. Urartu declined after the 714 BCE military campaign of the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II (r. 722-705 BCE) which was so decisive a victory that it thoroughly destabilized the region, making it an easy mark for later Scythian invasions. After the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE, the region was taken by the Medes who held it until the rise of the Achaemenid Empire c. 550 BCE.

The region's location, and importance in trade, brought it into contact with Greek culture and this interaction would define Sophene (and later Commagene) as a cultural blend of Armenian, Greek, and Persian influences, traditions, and religious practices. The Orontid ruling house was Zoroastrian but they were among those who encouraged the worship of the goddess Anahita, one of the most popular deities of the Early Iranian Religion which Zoroastrianism had replaced.

Under Zoroastrianism, Anahita continued in popularity as an aspect of the one, true god Ahura Mazda but, in some regions, she was worshipped as she had been in pre-Zoroastrian Persia. The temples and shrines to Anahita, and the seeming polytheism represented by shrines to other deities (such as Mithra), encouraged a comfortable rapport with Greek merchants who came from a polytheistic tradition and would have recognized aspects of their own goddesses in Anahita. This rapport, naturally, encouraged closer contact and a further blending of Armenian, Persian, and Greek cultures.

After the Achaemenid Empire fell, Sophene asserted itself as a separate kingdom, breaking away from the satrapy of Greater Armenia to form its own under the Seleucids. Its capital was the town of Carcathiocerta (modern-day Egil, Turkey) and its major urban trade center was Arsamosata (later known as Samosata, modern-day Samsat in the Adiyaman Province of Turkey). This new satrapy remained a cohesive entity under the Orontid satraps Sames I (r. 290-260 BCE) through Ptolemaeus of Commagene (r. as satrap 201-163 BCE) until, as noted Ptolemaeus founded Commagene.

Early Kings & Antiochus I Theos

Ptolemaeus claimed descent from the third Achaemenid king Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE) to legitimize his reign and moved the capital of his new kingdom to Arsamosata, which was then renamed Samosata. He expanded his kingdom into Cappadocia without resistance from the Seleucid Empire which, between 163-145 BCE, was in steady decline as it was ruled by three kings, in quick succession, who cared more about their own comfort and position than governing.

He patterned the administration of his kingdom on the Seleucid model, dividing his realm into satrapies overseen by a governor who collected taxes, sent them to the king, and were responsible for providing troops for the army. Greek was the official language of the kingdom but Armenian and Persian were also spoken. Little else is recorded of his reign but he set the paradigm of the later kings in claiming legitimacy based on their familial connection to the Achaemenid Empire.

Ptolemaeus was succeeded by his son Sames II (r. 130-109 BCE, also given as Samos II Theosebes Dikaios) who fortified Samosata and is mostly known through coins issued during his reign and inscriptions on Mount Nemrut. It was possibly Sames II who developed the major cities of Commagene: Samosata, Arsameia on the Nymphaios, and Arsameia on the Euphrates. All three cities would later reach their height of grandeur under Antiochus I Theos.

Sames II was succeeded by his son Mithridates I Callinicus (r. 109-70 BCE) who reigned during the Mithridatic Wars (89-63 BCE) between Rome and Mithridates VI of Pontus (r. 120-63 BCE). Concerned for his kingdom's survival in the midst of these hostilities, Mithridates I Callinicus married Laodice, daughter of the Seleucid king Antiochus VIII Grypos (r. 125-96 BCE) who was the son of the powerful Cleopatra Thea (l. c. 164-121 BCE). Cleopatra Thea was known as the power behind the Seleucid throne at this time, but her various schemes did nothing but hasten the Seleucid decline and no help came for Mithridates I Callinicus or the people of Commagene.

Tigranes the Great of Armenia (r. 95-56 BCE) marched across Commagene during this time, meeting no resistance, and claimed it as part of his Kingdom of Armenia after the Seleucids were no more than a phantom presence and while Rome and Pontus were at each other's throats. Mithridates I Callinicus could do nothing about Tigranes' conquest and so became a vassal king.

He was succeeded by Antiochus I Theos who consistently tried to balance all three sides of the conflict – Pontus, Rome, and Armenia – to maintain a separate peace for himself while also being ever-mindful of Parthia to the east. Once Mithridates VI of Pontus was defeated, however, and then Tigranes surrendered to Rome, Antiochus I Theos – though personally more loyal to Parthia – pledged himself to Pompey the Great (l. 106-48 BCE) of Rome. He was rewarded with lucrative trade agreements between regions to the east, including merchants of the Parthian Empire (227 BCE - 224 CE), and those of Roman Mesopotamia and Cilicia.

Antiochus I Theos maintained his legitimacy as a Persian king via his connection to Darius I but expanded this by claiming direct descent, through his mother Laodice VII Thea (b. c. 122 BCE), from Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE), founder of the Seleucid Empire, and Ptolemy I Soter (r. 305/304-282 BCE) of the Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt, as well as others who had served as generals of Alexander the Great. He thereby established himself as a Greco-Persian monarch and assumed the title of 'Antiochus, the just god, friend of Romans and Greeks', which pleased Rome while, at the same time, arranging the marriage of his daughter, Laodice, to King Orodes II of Parthia (r. 57-37 BCE) and securing peace with the east.

His clever political maneuverings kept Commagene from being absorbed by either Rome or the Parthians and maintained social stability while he grew rich from trade. Believing himself to be a god in human form, he created a royal cult based upon worship of himself and including a pantheon of syncretized Greco-Persian deities. In order that he might live forever in the hearts of his people – and among his gods as their equal - he decreed a great mortuary complex be built at Mount Nemrut which included an enormous tumulus and ornate statuary of himself, the other gods, and protective animals.

Out of his vast treasury, he allotted a certain sum to be used in perpetuity to hold parties on Mount Nemrut at his tomb every year on his birthday and the date of his coronation. He explicitly stipulated that everyone who attended was to enjoy themselves fully by setting aside the cares and antagonisms they were involved in at the base of the mountain before making the ascent to his celebration. He also revitalized the three major cities of Commagene, possibly reinforcing the walls around Samosata of Sames II, improved the efficiency of Ptolemaeus' original administrative vision, and brought the kingdom to an economic and cultural height it would not see again until the reign of Antiochus IV, the last king of Commagene.

Although Antiochus I Theos managed to maintain friendly relations throughout his reign, he was finally forced to choose sides by his father-in-law Orodes II and backed Orodes' son, Pacorus I (d. 38 BCE) in a war in Syria against Rome. Pacorus I was defeated and killed and the victorious Roman general, Publius Ventidius Bassus, came after Antiochus I Theos for betraying Rome, confining him under siege at Samosata. Antiochus tried to bribe his way out of trouble but Ventidius Bassus rejected his offer.

Mark Antony (l. 83-30 BCE) took over the siege when it became clear Ventidius Bassus could not break the fortifications, but he had no better luck and withdrew after accepting a bribe of 300 talents, significantly less than what Antiochus had offered Bassus earlier. Antiochus I Theos was killed by the Parthian king Phraates IV (r. 37-2 BCE) in 38 BCE in a coup in which he assassinated Orodes II (Phraates IV's father) and his wife Laodice, the brothers and half-brothers of Phraates IV, and Antiochus I Theos of Commagene who would have sought revenge.

Later Kings & Antiochus IV

He was succeeded by his son Mithridates II (r. 38-20 BCE) who allied himself with Mark Antony of Rome in his conflict with Octavian (the future Augustus Caesar, r. 27 BCE - 14 CE). Mithridates II had co-ruled with his father and was no doubt present at Antony's siege of Samosata when Antony had proved himself more reasonable than Bassus. Mithridates II proved his loyalty to Antony by personally commanding his own forces at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE at which Antony and Cleopatra VII of Egypt were defeated by Octavian. He afterwards swore loyalty to Augustus and continued to align his kingdom with Rome's interests. After his death, he was succeeded by his son Mithridates III (r. 20-12 BCE) about whose reign almost nothing is known.

Mithridates III was succeeded by his son Antiochus III Epiphanes (r. 12 BCE - 17 CE) whose reign was also unremarkable except for his unexpected death which left Commagene without a king. Antiochus III's two children – Antiochus IV (l. c. 17 - c. 72 CE; r. 38-72 CE) and Iotapa (r. 38-52 CE) – were too young to assume the throne and the court counselors, apparently, refused to appoint a regent. They instead appealed to Rome for help in finding a king and Rome responded by simply taking control of the kingdom, holding it in trust for Antiochus IV between 17-38 CE. Antiochus IV and Iotapa were taken to Rome, granted Roman citizenship, and raised as Romans.

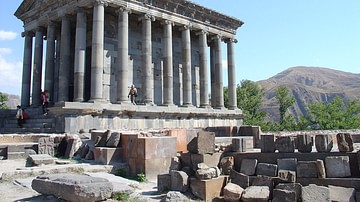

Antiochus IV used Caligula's money to build himself a grand city on the coast of Cilicia (now part of Commagene as Caligula's gift) known as Antiochia ad Cragum (“Antioch on the Cliffs” or “Antioch at Cragus”). The city incorporated Greek, Luwian, Hittite, Persian, and Armenian architecture, symbolism, and ornamentation to represent all the different ethnic groups of Commagene. A grand temple (55x33.8 feet/16.465x10.32 meters long) was built, ornamented with indigenous designs, notably the six-petal flower of the Luwians and Hittites who first inhabited the region. Antiochus IV also decreed a great bath complex be constructed which measured 114 feet long by 65 feet wide (35 x 20 meters), encompassing an area of 5, 249 square feet (1,600 sq. meters), which was open to the public. A colonnaded street brought visitors from the city's gate to an ornate portico by the pool with a mosaic floor. The mosaic at Antiochia ad Cragum, in fact, is the largest ever found in modern-day Turkey and exemplifies the wealth Antiochus IV lavished on his city.

Conclusion

His sister-wife Iotapa died in 52 CE and he had another city, Aytap, built in her honor down the coast. He was, at this time (c. 71 CE) among the richest tributary kings of Rome and enjoyed a good relationship with the Roman government. Commagene at this time was at its greatest height since the reign of Antiochus I Theos and Antiochus IV had just ingratiated himself to the new emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) by supporting him over other contenders for the throne and sending him and his son troops.

In 72 CE, however, a senator named Lucius Junius Caesennius Paetus (governor of Roman Syria c. 70-72 CE) accused Antiochus IV and his sons of plotting to overthrow Vespasian. There was no evidence of any conspiracy on the part of Commagene, but this did not seem to matter. Vespasian was notoriously paranoid, and the wealth and popularity of Antiochus IV was indisputable, and so Vespasian listened to Paetus and gave him leave to march on Antiochia ad Cragum without ever even asking Antiochus IV to refute the charge.

According to some accounts, the sons of Antiochus IV met Paetus' troops in battle, according to others, there was no battle at all, but all agree that Antiochus IV himself did not raise arms against Rome. He most likely surrendered to Paetus, who clearly had only made the accusation to acquire Commagene's wealth, but this is unknown. He left the city afterwards, lived in Cilicia Campestris, Greece, and finally at Rome. What happened to Paetus is unknown, but Antiochus was received with respect at Rome, as were his sons, and must have died there, although no death date is known. Vespasian abolished the Kingdom of Commagene the same year and absorbed the region into the province of Cilicia.

Today, the Kingdom of Commagene is remembered primarily through the monumental site of Nemrut Dagi on Mount Nemrut, (rediscovered in 1881 CE, and a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1987 CE), and the various other building projects, reliefs, and statuary from the reign of Antiochus I Theos and his successors. The ruins of Antiochia ad Cragum and Aytap also remain popular tourist attractions as well as communal recreation areas, down by the water, for the local population. Nemrut Dagi, however, is the central monument to Commagene and its kings, drawing millions of visitors every year from around the world, and fulfilling the wish of Antiochus I Theos that his name should live on forever.