The Kappel Wars (also known as the Wars of Kappel) were armed conflicts between Protestants and Catholics in Switzerland during the Swiss Reformation. The First Kappel War ended before it began in 1529, while the second, in 1531, concluded with a Catholic victory and the death of the Protestant reformer Huldrych Zwingli.

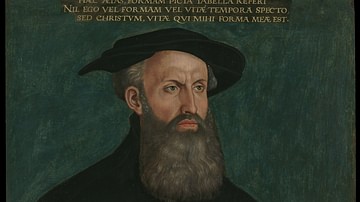

Both events took place near the village of Kappel am Albis near Zürich, Switzerland. The conflicts were encouraged by Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) in an effort to make all the cantons (provinces) of the region convert from Catholicism to the Protestant vision. Zwingli believed a united, Protestant, Switzerland would reflect the ideal state as an embodiment of the early Christianity depicted in the biblical Book of Acts.

The First Kappel War was a mobilization of Protestant troops in response to the execution of a Reformed priest in Catholic territories, which then forced Catholic forces to respond. The differences were resolved peacefully before battle, but the underlying issues remained. In 1531, Zwingli again encouraged Zürich to attack the Catholic cantons but was forced to settle for a blockade intended to starve them into conversion.

In response to the blockade and Zwingli's continued calls for forced conversion, the Catholic cantons declared war on Zürich in October 1531, catching the city off guard. The Catholic and Protestant forces met at Kappel am Albis on 11 October 1531, and the Protestants, poorly mobilized and lacking strong leadership, were defeated in under an hour with 500 casualties, including Zwingli.

The Kappel Wars significantly damaged the Reformation movement in Switzerland as Zwingli was blamed for starting the conflict and the resultant 500 deaths. The movement was saved and stabilized by one of Zwingli's supporters, the theologian Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575), whose more moderate stance allowed for conversation and compromise. After the wars, and despite Bullinger's efforts, animosity between the Catholics and Protestants of Switzerland continued, but for a brief time at least, Catholic cantons and Protestant cantons were allowed to observe their respective interpretations of Christianity in peace.

Zwingli & Reformation

Although the region of modern-day Switzerland was technically part of the Holy Roman Empire, it was actually a confederation of 13 cantons, each operating more or less independently, since 1499. The confederation, like all of Europe prior to the Reformation, adhered to the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, understood as the sole authority on spiritual matters. The medieval Church had no problem with supporting and contributing to armed conflict when that served its purposes, however, and priests encouraged young men to enlist in the mercenary pension system through which they were paid to fight for the causes of surrounding political powers.

Zwingli was ordained a priest in 1506 and sent to minister in the village of Glarus. In 1513, he accompanied the Glarus mercenaries on campaign as their chaplain, and experiencing the horrors of war, he embraced the pacifism of the humanist priest, philosopher, and theologian Desiderius Erasmus (l. 1466-1536) and criticized the mercenary system as well as armed conflict generally as anti-Christian. Erasmus, whom he met in 1514 and 1516, was a significant influence on the young Zwingli on several levels but notably regarding the need for reform of the vision and policies of the Church.

Although Erasmus never joined the Reformation movement, he advocated for the reform of what he saw as abuses and corruption within the Church, and Zwingli embraced these views. When he was appointed as people's priest to the Grossmünster (Great Church) in Zürich in 1519, Zwingli began by discarding the Church's liturgy and reading directly from the Gospel of Matthew, interpreting and commenting on it as he would then do with other biblical texts.

By 1521, the German Reformation movement of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) had divided that region and was inspiring similar rejections of ecclesiastical authority elsewhere. Zwingli, who had recently been appointed a canon (magistrate) and become a citizen of Zürich, initiated the Reformation in the city in 1522 when he rejected the Church's tradition of Lenten fasting and argued that there was no biblical support for the prohibition on eating meat during Lent nor for Lent itself. The Church called for Zwingli's dismissal, but the city council instead allowed for a debate between Zwingli and church officials to resolve their differences.

In 1523, Zwingli's 67 Articles were presented at the First Disputation where he easily defeated the Catholic delegation. Encouraged by the council's support and his victory, Zwingli – and then his followers – began a systematic rejection of the teachings and traditions of the Catholic Church, insisting on the Bible as the sole authority in both spiritual and secular matters, and denouncing the traditional observances and policies of the Church.

Zwingli's friend and supporter Leo Judd (l. 1482-1542) advocated for the removal of icons and images from churches, which led to social unrest and the destruction of statuary and stained-glass windows in churches. Zwingli and Judd influenced the young Lutheran theologian Heinrich Bullinger, who also began preaching against icons in the municipality of Bremgarten in the Aargau region, encouraging the same protests against religious iconography.

Growing Tensions

As Zwingli's Reformed movement spread, it was opposed by Catholics in cantons that chose to remain faithful to the Church. To these people, Zwingli's ideas were dangerous heresies to be rejected if one hoped to avoid the fires of hell or purgatory after death. The medieval religious understanding encouraged by the Church was that hell, purgatory, and heaven were absolute certainties, and so embracing a false faith had dire consequences in that one would suffer for one's mistake eternally.

It was not only considerations of one's afterlife that caused Catholic cantons to reject Zwingli's call for reformation but also the disruption of traditional rites, rituals, and practices the movement caused. By 1524 in Zürich, annual Christmas observations were abandoned, processions were not observed, and the Easter rituals of 1525 were ignored. The Second Disputation of 1523 had left the choice up to individual parish priests to decide their own course, and many of them sided with Zwingli who denounced all the sacraments of the Church except baptism and the Eucharist. He also claimed the priesthood itself was unbiblical, the pope was a false authority, that there was no biblical support for purgatory, that Christ was not present in the celebration of the Mass, and that the Church had come to exist only to serve itself, not the true Christian vision.

His supporters, now believing they had God's truth, rejected all practices associated with Catholicism, but since the Church had informed the lives of Europeans for centuries by this time, Church doctrine dictated and ordered not only how births, marriages, and deaths were observed but also one's daily activities. The new vision, therefore, required a complete overhaul of customs and observances, which traditionalists resisted. Scholar Randolph C. Head observes:

Reimagining authority also meant rethinking many practices of everyday life, as well. If marriage was not a sacrament, then communities and families had to find new ways to understand the relationships among spouses and their kin. Who could regulate – and perhaps dissolve – marriages and the ties between families that they created? Who, if not the clergy, should sanction adultery or manage charity? If individuals reading Bible texts could question pastors and magistrates, then the Word too took on an expanded role in many situations. If mutually hereticizing congregations shared a space for worship, that sacred space was no longer the same. Because religion was deeply embedded in every institution of early modern Europe, changed religious understandings required change in every aspect of life. (Rublack, 179)

There were many who simply rejected this call for change and preferred to continue with the traditions they had always known, while those advocating for reform insisted that everyone needed to embrace the truth as revealed by Zwingli's teachings. In Zwingli's view – and increasingly among his supporters – there was no middle ground for compromise because of their conviction that the Reformed vision represented God's will as revealed through the scriptures.

The First Kappel War

In 1528, the canton of Bern joined the Reformation, and Zwingli began advocating for a united Reformed Switzerland, with the Bible as its final authority. Constance joined with Zürich and Bern in the Christian Civic Union, and then five other cantons joined them. The five Catholic cantons then banded together as the Christian Alliance and signed a treaty with Catholic Austria to assist them if they were attacked. The Catholic Alliance was therefore formed only for defense, but the Christian Civic Union was formed in hopes of establishing a united Reformed Switzerland. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch notes:

The Union took its cue from Zwingli's vision of his beloved city of Zurich as a united community of Christian believers working to build a godly society; it was also unmistakably aggressive in intention. There is disagreement about the extent of Zwingli's ambitions for the Union, but there is no doubt that his immediate aim was to pull over into evangelical faith the so-called 'Mandated Territories' scattered throughout Switzerland, which were mandated to be jointly ruled by all the Swiss cantons; with cantons now dividing between reform and traditionalism, these might be maneuvered towards religious reform. (175)

To peacefully convert the Catholic cantons, Zwingli initiated a campaign of Reformed preachers, carefully trained by him in Zürich, who would spread his vision among the Mandated Territories and the staunchly Catholic cantons. The First Kappel War was launched after a Protestant preacher was arrested and executed as a heretic in Catholic Schwyz. Zwingli abandoned his early pacifism in the interests of a united Switzerland and mobilized Zürich to attack.

His advocacy for warfare seems to have been encouraged by Zwingli's persecution of the Anabaptists - a Reformed sect inspired by his teachings which he then sought to suppress as extreme - as he had preached against them and then supported their persecution and execution. Zwingli's call for the forcible conversion of Catholics follows the same pattern as that suggested by his policy toward the Anabaptists.

The Protestant and Catholic forces met at Kappel, with the Catholics significantly outnumbered after Austria failed to send troops, but before hostilities could commence, a delegation from Bern arrived and negotiated a peace. While these talks went on, the armies remained on the field, but neither side was interested in provoking conflict. According to the Catholic playwright and mercenary Johannes Salat (d. c. 1561), who was present at the time, the two armies shared milk and bread in an event later popularized by Bullinger as the Kappeler Milchsuppe (the Milk Soup of Kappel), a symbol of how Protestants and Catholics could coexist peacefully.

While the armies waited for word from their leaders to begin hostilities, an armistice was concluded and peace declared. Under the terms of the treaty of the Peace of Kappel am Albis, the Catholic cantons had to dissolve the Christian Alliance, nullify their treaty with Austria, and allow Protestant preachers to teach in their regions without fear of persecution, and, in return, Zürich promised no further aggression. MacCulloch comments:

Zwingli gained his aim for the Mandated Territories…he secured the right of each parish or village to choose by a majority of the male inhabitants which religion to adopt. Majority voting was a new idea in communities which had previously made decisions by reaching consensus; it was also an obviously useful device for overcoming traditionalist minority obstruction. Zwingli extended the principle by organizing territorial assemblies, including both clergy and lay delegates, who would make common decisions on worship for the parishes of each territory. (175)

Zwingli had stipulated further terms for the armistice, which were rejected, and he felt this policy of majority voting would take too long in realizing his goal of a completely Reformed and united Switzerland, so he continued to advocate for forced conversion of the Catholic cantons. His calls for armed conflict increased once the Catholics refused the stipulation of unhindered Protestant preaching in their cantons – a point in the treaty that had never been fully clarified – but the other Protestant regions resisted. In an attempt to force conversion by less drastic means and also pacify Zwingli, the Protestants blockaded the Catholic cantons in May 1531, cutting off supplies of salt and grain.

The Second Kappel War

Instead of encouraging conversion, the blockade only enraged the Catholics, who understood it as an act of aggression by heretics against followers of the one true Church. The blockade proved ineffective anyway, as supplies reached the cantons, in lesser quantity, by other routes, and it was abandoned. The Catholic cantons, however, decided to strike back before some other, more effective, Protestant initiative could be launched.

They marched on Zürich in October 1531, catching the city by surprise. Although reports of the movement of a large force reached Zürich before 9 October, they were not taken seriously. Zwingli and the city council hurriedly mobilized their forces and called for help from other cantons, but this was refused. Bern and the others were not interested in a war that could only weaken their own positions and possibly invite invasion by Catholic forces from surrounding nations.

The Protestant force of around 2,000 met the Catholic army at Kappel am Albis on 11 October 1531 in a battle that lasted less than an hour. Zürich lost 500 combatants, which included Zwingli and other priests of the city. According to Bullinger's later account, Zwingli was mortally wounded and then killed by a Catholic captain. Afterwards, his corpse was tried for heresy, condemned, cut into pieces, and burned. The offal of swine was thrown into the fire, and the ashes afterwards mixed and dispersed. The Catholics withdrew but attacked again on 24 October, completely defeating Zürich.

Conclusion

The Second Kappel War was a devastating defeat for Zürich, and the city was forced to accept terms dictated by the victors. No doubt to their surprise, these terms were remarkably lenient as Head observes:

The [Second Peace of Kappel] sealed on November 20, 1531, favored the victorious religious traditionalists, but still recognized the existence of two faiths and set out guidelines for their coexistence. Crucially, each canton remained free to choose either the "true undoubted faith" of the Catholics or the "faith" of the Zwinglians. The peace was thus a moderate document that reaffirmed the principle that sovereigns enjoyed a choice among Christian confessions – a principle that later spread to the entire Holy Roman Empire. (Rublack, 177)

Zürich was left physically untouched by the war, but the defeat seriously undermined the Reformation effort that had previously had such widespread support. Zwingli was blamed for the deaths of the 500 in battle, and the Reformation's momentum stalled. MacCulloch writes:

[The defeat was] the end of the Christian Civic Union, the end of fruitful political alliance with German evangelical cities to the north, and the end of any attempt to impose the Reformation by force in Switzerland. It was little thanks to Zwingli that his work in Zurich did in fact recover. The city's Reformation was steered back to stability by Heinrich Bullinger, a wise and patient man and a great preacher. (176)

Bullinger had become more moderate as Zwingli's radicalism increased and succeeded him as leader of the Reformed movement. He would later co-author the First Helvetic Confession with Leo Judd in 1536 and write the Second Helvetic Confession in 1562. Known as the Helvetic Confessions, these documents detailed the articles of faith of the Swiss Reformed Movement and were adopted by John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) and his followers. Eventually, they became the religious confession of Reformed congregations in as well as outside of Switzerland. In Zürich, however, immediately following the defeat, Bullinger's whole focus was on saving the movement.

He continued to defend Zwingli but prudently avoided politicizing the movement and discouraged priests from making overt political statements in an official capacity. Having taken over Zwingli's position as the people's priest at Grossmünster, he kept careful watch over his congregation and arranged to be kept constantly informed of every parish he was responsible for in order to prevent the kind of radicalization that had led to the Kappel Wars. Through careful control and moderation, Bullinger not only saved but more fully developed the movement whose founder had nearly destroyed it, allowing for Calvin to complete the work of Reformation that Zwingli had begun.