Emerging from a small sect of Judaism in the 1st century CE, early Christianity absorbed many of the shared religious, cultural, and intellectual traditions of the Greco-Roman world. In traditional histories of Western culture, the emergence of Christianity in the Roman Empire is known as “the triumph of Christianity.” This refers to the victory of Christian beliefs over the allegedly false beliefs and practices of paganism. However, it is important to recognize that Christianity did not arise in a vacuum.

Roots in Second Temple Judaism

Jews claimed an ancient tradition with law codes for daily life (the Laws of Moses) and revelations from their god through Prophets. While recognizing various powers in the universe, Jews nevertheless differed from their neighbors by only offering worship (sacrifices) to their one god, Yahweh. After suffering several national defeats by the Assyrians in 722 BCE and the Babylonians in 587 BCE, their prophets claimed that God would eventually restore Israel to its former independence. In those 'final days' (eschaton in Greek), God would designate a descendant of David, an 'anointed one' (Messiah in Hebrew, or Christos in Greek), who would lead the righteous against the enemies of Israel. God would then establish a new Eden, which came to be known as 'the kingdom of God.'

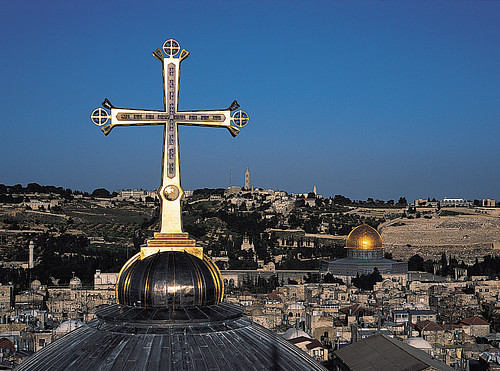

After a short-lived rebellion against Greek rule (the Maccabean Revolt, 167 BCE), Galilee and Judea were conquered by Rome (63 BCE). By the 1st century CE, many messiah figures rallied Jews to call upon God to help them overthrow the overlords. Most of these figures were killed by Rome for stirring up mobs against law and order. A sect of Jews known as Zealots convinced the nation to rebel against Rome in 66 CE, which ended in the destruction of Jerusalem and their temple (70 CE).

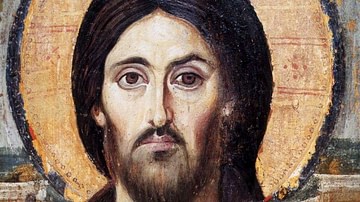

From all of the evidence, Jesus of Nazareth was an end-time preacher, or an apocalyptic prophet, proclaiming that the kingdom of God was imminent. He was crucified by Rome (between 26-36 CE), perhaps for stirring up crowds at the festival of Passover. Crucifixion was the Roman penalty for rebels and traitors; preaching a kingdom other than Rome was subversive. Shortly after his death, his disciples claimed that he had risen from the dead. Whatever this experience was, it motivated them to mission or to spread the 'good news' ('gospel') that the kingdom of God would arrive soon.

The followers of Jesus first took this message to the synagogue communities of Jews in the Eastern part of the Roman Empire. Many Jews did not believe that Jesus was the expected Messiah, but to the surprise of these apostles (messengers), Gentiles (pagans) wanted to join the movement. This unexpected occurrence raised questions of inclusion: should these pagans become Jews first, entailing circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath observance? At a meeting in Jerusalem (ca. 49 CE, The Apostolic Council), it was decided that pagans could join without becoming Jews. However, they had to observe some Jewish principles such as draining blood from meat, sexual morality, and the cessation of all idolatry (Acts 15). By the end of the 1st century, these Gentile-Christians dominated the Christianoi (“the followers of the Christ”).

Paul, a Pharisee, was the founder of many of these communities. He claimed that Jesus told him in a vision to be his “apostle to the Gentiles.” Jesus was now in heaven but would soon return. This concept was known as the parousia (or 'second appearance'), and rationalized the problem that the kingdom did not appear during Jesus' lifetime; what the prophets proclaimed would be fulfilled upon his return. At that time, current society (and its social conventions and class distinctions) would be transformed.

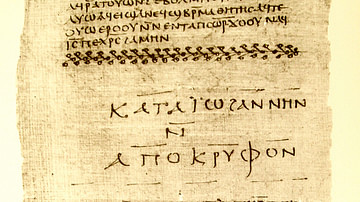

With the belief that Jesus was now in heaven, Christ became an object of worship. Paul claimed that Christ had been present at creation, and that “every knee show bow” before him (Phil. 2). In the fourth gospel of John, Christ was identified as the philosophical principle of the logos, or the rational principle of the universe that became flesh (the doctrine of the Incarnation). We have very little information on how early Christians worshipped Christ. Worship in the ancient world consisted of sacrifices. For Jews (and then Christians), this element was removed with the destruction of their Temple in 70 CE. At the same time, ex-pagan Christians ceased the traditional sacrifices of the native cults.

In the Acts of the Apostles, we have stories of Peter and John healing people “in the name of Jesus.” There was an initiation rite of baptism, hymns and prayers to Christ, and a meal known as the Last Supper, a memorial of Jesus' last teaching. Christians addressed Jesus as 'Lord,' which was also a Jewish title for god. Jews could acknowledge the exaltation of Jesus to heaven as a reward for a martyr's death, but placing Jesus on the same level as God created a barrier between Jews and Christians.

The Spread of Christianity

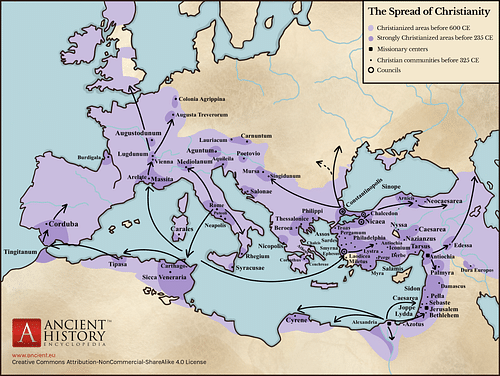

In Greco-Roman culture people claimed ethnic identity from ancestors; you were literally born into your customs and beliefs. Conversion (moving from one religious worldview to another) was not common as your religion was in the blood. Christianity taught that ancestry and bloodlines were no longer relevant. According to Paul, faith (pistis, 'loyalty') in Christ was all that was needed for salvation. This new idea resulted in a religious movement no longer confined to a geographic area or an ethnic group. Christianity became a portable religion available to all.

The idea of salvation was another innovation. Jews had articulated salvation as the restoration of the nation of Israel. Pagans had no similar concept but some did have concerns about their existence in the afterlife. Paul wrote that Christ's death was a sacrifice that eliminated the punishment for the sin of Adam which was death (the doctrine of atonement). For this first generation of Christians, physical death was no longer a reality; they would be transformed into “spiritual bodies” when Christ returned (1 Cor. 15). As time passed and Christ did not return, Christians accepted the death of the body but were promised a reward in heaven.

Christianity shared some elements with the Mystery cults (such as Demeter and Dionysus) that were popular in the Hellenistic period. These cults required initiation and offered secret information on both an improved life in this world as well as a smooth transition to a good afterlife. The Mysteries also utilized the concept of a dying and rising god.

Christianity did not spread overnight “like wildfire” as it was previously suggested. Initiates spent three years learning Christian teachings, followed by their baptism, which was usually held on what became the feast day of Easter. The initiate was naked as an indication of a rejection of their former life, submerged in the water, and then donned a new robe as the sign of being "reborn". Adult baptism was the norm until roughly the 4th and 5th centuries CE when infant baptism became the norm due to high infant mortality rates.

Hierarchy, Celibacy & Monasticism

Christianity did spread far and wide, with small communities as far away as Britain and sub-Saharan Africa. However, there was no central authority, such as the Vatican, to validate various beliefs and practices. Numerous and diverse groups existed throughout the Empire. Bishops communicated with each other and their letters demonstrate often rancorous debates.

Christians adopted the Greek system of political assemblies (ecclesia in Greek, English 'church') and the Roman system of an overseer (bishop) of a section of a province (a diocese). In the 1st century CE, bishops were elected as administrative leaders. An innovation in the office of bishop occurred sometime between the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. Bishops now had the power to absolve sins through their possession by the Holy Spirit. Deacons were elected initially as helpers in distributing charity and eventually became priests.

The pagan worldview included the importance of fertility (of crops, herds, and people) for survival. Sexual intercourse was considered necessary, natural, and enjoyable for both gods and humans. The Church Fathers expressed a disdain for these attitudes toward the body, influenced by similar philosophical views known as asceticism. Church leaders advocated celibacy (no marriage) and chastity (no sexual relations) as requisites for bishops and other leadership positions.

Beyond the leadership, Christians were encouraged to marry, recognizing the biblical command “to be fruitful and multiply.” However, sexual intercourse was limited to the sole purpose of procreation. Intercourse, when a wife was barren, was a concession to lust, now deemed a sin and something that only sexually immoral pagans indulged in.

The height of Christian asceticism was achieved by Anthony in Egypt (251-356 CE) when he turned his back on society and went to live in a cave in the desert. Others followed and were known as the Desert Fathers. They eventually were housed together in monasteries and provided an additional level of clergy, and the educated among them copied and illustrated Christian manuscripts.

Persecution & Martyrdom

By tradition, the Emperor Nero (54-68 CE) was the first Roman official to persecute Christians. The Roman historian Tacitus (56-120 CE) claimed that Nero blamed the Christians for the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE, although he was not a witness to the events. Nevertheless, the story has become embedded in the early history of Christianity. If Nero did indeed execute Christians, it was not official Roman policy at this time.

The decision to persecute Christians most likely began during the reign of Domitian (83-96 CE). A depleted treasury motivated Domitian to take action in two areas: he enforced the collection of the Jewish Temple tax and mandated worship at the Imperial Temples. After the destruction of their Temple, Domitian's father, Vespasian (69-79 CE), had ordered the Jews to continue paying the Temple tax, now sending it to Rome as war reparations, but apparently, no one enforced this until the reign of Domitian. In seeking out tax evaders among Jews, his officials became aware of another group who worshipped the same god but were not Jews and thus not responsible for the tax.

The Imperial Cult began with the deification of Julius Caesar after his death (44 BCE). The common people claimed that Caesar was now “among the gods.” Octavian created Imperial temples that both honored Caesar and the imperial family. The Imperial Cult served as propaganda and brought in funds from the sale of priesthoods. Domitian insisted on being addressed as “Lord and God” and ordered everyone to participate in his cult. Jews had been granted exemption from traditional cults by Julius Caesar as a reward for his Jewish mercenaries. Christians, however, did not have this “get out of jail free card.”

Christians were charged with the crime of atheism. Their refusal to appease the gods by sacrificing to them was perceived as a threat to the prosperity of the Empire, which was equivalent to treason. Christians were executed in the arenas, often being mauled and eaten by lions. Lions and other wild animals were utilized in the venatio games by specially-trained animal hunters (bestiarii). It was convenient to utilize these animals as executioners for the state.

Christians borrowed the concept of martyrdom from Judaism, where anyone who died for their faith was immediately taken into the presence of God. Martyrdom, therefore, became very attractive for Christians and many stories were told of their bravery and conviction in the face of death. Such devotion served as propaganda for the faith.

Despite Christian tradition (and Hollywood), persecution was never the subject of Empire-wide edicts until the second half of the 3rd and the beginning of the 4th centuries CE. Nor were there thousands of victims. In 300 years, we have records that indicate the sporadic nature of persecution which depended upon circumstances. Whenever there was a crisis (foreign invasion, famine, plague) Christians became scapegoats for angering the gods. In between, Romans left Christians alone for the most part.

Orthodoxy & Heresy

The pagan world accepted the plurality of diverse approaches to the gods with an emphasis on correct rituals rather than any consensus on doctrine. The Church Fathers of the 2nd century CE developed an innovation with the concept of orthodoxy, or the idea that there was only one “correct belief.” This was matched by its polar opposite, heresy (Greek, airesis, or 'choice,' as in a choice of a particular philosophy).

Under the umbrella term, 'Gnostics,' some Christians offered a different view of both the universe and salvation in Christ (from the Greek, gnosis, 'knowledge'). For many Gnostics, all matter in the physical universe was evil, including the human body. Christ did not manifest in a body, and therefore, the crucifixion and resurrection were not important for salvation. Rather, Christ only appeared in human form (Docetism) to reveal that humans contained a divine spark of God that was trapped in the body. Jesus' teaching provided the key to liberate this spark and help it return to its source.

Adversos Literature: An Identity Separate from Judaism

A specific type of literature emerged in the 2nd century CE, directed against Jews and Judaism, which coincided with increased persecution of Christians. Christians claimed they should have the same exemption from state cults as the Jews because Christians were verus Israel, the “true Israel.” Christian interpretation of the Jewish Scriptures through allegory demonstrated that wherever God appeared in the Scriptures, it was actually Christ in a pre-existent form. Christians claimed the Scriptures as their own and a "new covenant" now replaced the old. The adversos literature contributed to a Christian identity now separate and distinct from Judaism in practice, but with an ancient tradition which would give them respect. These treatises were highly polemical, malicious, and full of standard rhetoric at the time against an opponent. Unfortunately, many of these arguments became the basis for the later charges against Jews in the Middle Ages and beyond.

The Conversion of Constantine

By 300 CE, Emperor Diocletian (284-305 CE) had organized the Roman Empire into East and West. When he died in 306 CE, various co-rulers vied to return to one-man rule. In the West, the battle was between Maxentius (306-312 CE) and Constantine I (306-337 CE). Constantine later told the story that the night before the battle (at the Milvian Bridge in Rome), he saw a sign in the sky (either chi and rho, the first two letters of Christ, or a cross) and heard a voice that commanded “in hoc signo vinces” (“in this sign conquer”). Constantine claimed that he won the battle with the support of the Christian god.

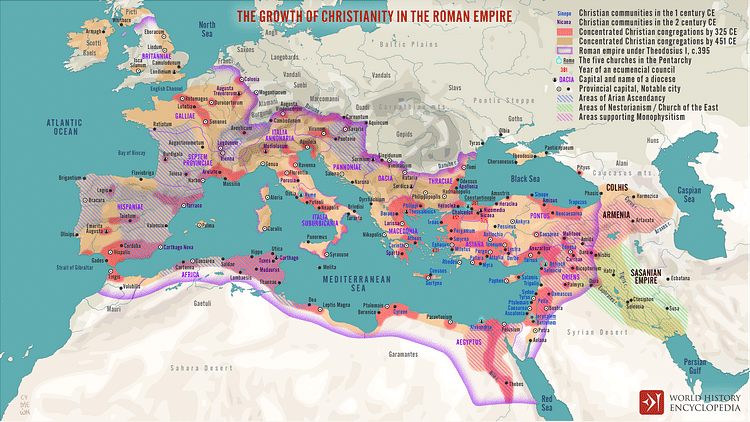

In conjunction with the surviving ruler of the East, Licinius, The Edict of Milan was issued in 313 CE, granting Christianity the right to legally assemble without fear of arrest or persecution. Christianity now joined the hundreds of other pagan cults, although Constantine favored Christians through tax exemptions and funds for building churches.

A Christian EMPIRE

Constantine was interested in both unifying the Empire as well as the Church. He adopted the teachings of the Church Fathers as the core of Christian belief. However, a controversial teaching by a presbyter in Alexandria, Egypt, Arius, caused riots throughout the Empire. According to Arius, if God created everything in the universe, then Christ was a creature and thus subordinate to God. In 325 CE, Constantine invited bishops to attend a meeting in Nicaea to define the relationship between God and Christ. The result was the Nicene Creed, a list of tenets that all Christians were to avow. God and Christ were of the “same essence,” both participated in creation, and therefore monotheism was maintained; God was one, with three manifestations. With the Holy Spirit of God as the manifestation of divinity on earth, this doctrine became known as the Trinity. Christians who challenged these beliefs were deemed heretics, now equivalent to treason. Their non-conformity threatened the prosperity of the now Christian Emperor and Empire.

In 381 CE, Theodosius I issued an edict that banned all cults except Christianity. In the 390's CE he ordered the cessation of the Olympic Games, dedicated to the ancient gods, and the closure of pagan shrines and temples. Some of these buildings were destroyed, but others were transformed into Christian churches.

By the 4th century CE, Christians combined the Jewish concept of martyrdom with Greco-Roman concepts of patron gods/goddesses of towns and cities. Christian martyrs were now understood in a similar position as mediators in heaven. The practice of pilgrimage to their tombs became "the cult of the saints."

When Constantine moved the capital to Constantinople in 330 CE, this created a temporary void in leadership in the West. By the 5th century CE, the bishop of Rome absorbed secular leadership as well, now with the title of 'Pope.' In the Eastern Empire (Byzantium), the Emperor remained the head of the state as well as the head of the Church until the conquest of Constantinople (Istanbul) by the Turks in 1453 CE.

Why did Christianity succeed? The conversion of Constantine certainly provided practical reasons for pagans to adopt the new religion. However, while introducing innovations, Christianity nevertheless absorbed many shared elements from Greco-Roman culture, which undoubtedly helped to transform individuals from one worldview to another.