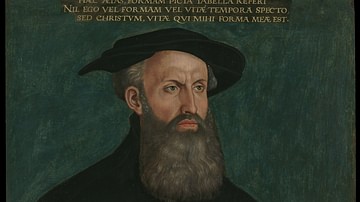

John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) was a French Reformer, pastor, and theologian considered among the greatest of the Protestant Reformation along with Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) and Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531). Calvin synthesized the differing views of Protestant sects with his own in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, regarded as one of the most important works of Protestant theology.

Calvin is recognized as one of the most influential reformers because The Institutes of the Christian Religion systematized the Protestant vision drawing on the beliefs of different sects established by Luther, Zwingli, and others. After Zwingli's death in 1531, Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575) took over as leader of the Reformed Church and acted as a kind of bridge between Zwingli's movement and Calvin while, at the same time, Calvin was directly influenced by Luther and Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560) as well as the reformers Guillaume Farel (William Farel, l. 1489-1565) and Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551). The result was a comprehensive vision of the earliest expressions of Protestant Christianity synthesized clearly by Calvin and clarified by his own theology.

Although Calvin is better known today, Bullinger was actually more popular and influential in his time and contributed a number of concepts associated with Calvin's later work, including covenant theology, while the concept of predestination, also closely associated with Calvin, was first suggested by Luther. Still, it was Calvin who would eventually become the most influential to the point where Protestants were frequently referred to as Calvinists. The Calvinists of England became the Separatists who objected to the Anglican Church and brought Calvinism across the Atlantic Ocean, establishing Plymouth Colony in 1621. Afterwards, Calvinism became the dominant Christian doctrine of New England in North America and continued to exert significant influence through the early years of the United States and even in the present day.

Early Life, Education, & Conversion

Calvin was born in Noyon, Picardy, in the Kingdom of France on 10 July 1509 and given the name Jehan Cauvin. His father, Gerard Cauvin, was a notary at the ecclesiastical court and his mother, Jeanne le Franc, died at some point before Calvin was twelve years old. He had at least three brothers, all of whom Gerard encouraged to study for the priesthood. When he was 12, Calvin was awarded a benefice (stipend) to study in Paris (as did his older brother) and learned Latin before enrolling at the College de Montaigu to study philosophy.

At some point c. 1525, Gerard had a falling out with the cathedral at Noyon and discouraged Calvin from further ecclesiastical study, enrolling him at the University of Orléans as a law student. In the course of his studies, he was introduced to the concepts of the humanist theologian, scholar, and philosopher Desiderius Erasmus (l. 1466-1536) as well as other humanist thinkers and writers including the jurist Andrea Alciato (l. 1492-1550), founder of the French legal humanist school.

Humanism emphasized the rights and responsibilities of the individual and focused on the present in contrast to church teachings which emphasized the divine and the afterlife. Although Erasmus always remained a member of the Catholic Church, he encouraged the humanist view, which included immersion in the classics of Greek and Roman literature. Calvin received his law license in 1532 but then began to lose interest in law and increasingly became drawn to theology, moving to Paris to continue his study of Latin, Greek, and classical works. He seems to have applied humanist concepts to the teachings of the Church and, possibly, this caused the spiritual crisis he later said he experienced prior to his conversion to the Protestant beliefs. Scholar Mack P. Holt comments:

Sometime [in 1533] Calvin experienced a conversion to the Reformation and left the Catholic Church. Details of his conversion are sparse, as Calvin only chose to comment on it very briefly a long time after the event in question. At the same time, he abandoned any thought of practicing law for the rest of his life and turned toward theology, though not the scholastic theology of the medieval church. (Rublack, 217)

Although Holt gives the year as 1533, it may have been 1530 or earlier. Luther's teachings had been translated and reached Paris by 1521 when they were denounced as heretical, and his books were burned. It may have been at this time that Calvin first read Luther, but this is unclear. Calvin chose to focus his written works almost wholly on Christianity without providing much in the way of biographical information.

He seems to have experienced an existential crisis during which he questioned the value of everything he had done up to that point in his life as well as the truth of the Church's vision. In 1533, Calvin's close friend Nicholas Cop (l. 1501-1540) delivered an inaugural address at the University of Paris advocating reform and was accused of the heresy of Lutheranism. Calvin seems to have been implicated as well and fled to Basel, Switzerland, to avoid persecution.

Strasbourg & Geneva

Luther's central argument was that scripture alone was the source of truth and an individual was justified by faith in God alone, not by works nor by following the teachings of the Catholic Church. Calvin responded to this message while in Basel by writing the first version of The Institutes of the Christian Religion (he would revise the work several times throughout his life), which expands on Luther's vision while also contradicting a number of his claims. He published the work in 1536 before leaving for Italy and then returning to France to find pro-Catholic forces were dominating the spiritual landscape and Protestant teachings unwelcome.

He left Paris for Strasbourg but was detoured to Geneva where he planned to stay only one night. The French Reformer Guillaume Farel, who was trying to advance the Reformation in the city, convinced him that God had called him there to help in the work, and Calvin agreed to stay. Holt writes:

Although Calvin was completely self-taught in theology and had no formal ecclesiastical training of any kind, Farel got him appointed as "lecturer in Holy Scripture" in Geneva. To be fair, Calvin's Humanist education as well as his biblical studies in Paris had given him a very solid foundation for his theological ideas. And there is no doubt that both Farel and Bucer, his elder mentors, considered the young Calvin as their superior in terms of his knowledge of Scripture. (Rublack, 217)

Farel and Calvin at first made considerable progress in Geneva, but their insistence on having things their own way, without compromise, resulted in the city council asking them to leave the city in 1538. The reformer Martin Bucer invited him to come and preach in Strasbourg, where he became pastor of a church of French protestant refugees. In Strasbourg, he revised The Institutes of the Christian Religion, expanding it from 6 to 17 chapters, wrote his first biblical commentary on the Book of Romans (he would eventually write on almost every book of the Bible), and lectured at the academy every day while preaching two sermons every Sunday.

In 1540, he married the widow Idelette de Bure (l. 1500-1549), who had two children from her previous marriage. Idelette supported Calvin's ministry, and their marriage was a happy one. Calvin's time in Strasbourg was a significant period in shaping his views as he was directly influenced by Bucer on how Christianity should be practiced instead of emphasizing details of theology. Instead of the abstract, Bucer focused on the practical application of Jesus Christ's teachings in people's daily lives. Bucer's emphasis on 'reformation of the laity' is clearly seen in Calvin's works as is the influence of Bullinger with whom Calvin had begun to correspond.

In 1541, Geneva sent word it would like to have Calvin back as Reformation momentum had flagged and church attendance was down. Calvin refused but, after being promised it was only a temporary reassignment of six months, relented and returned to Geneva with his wife and family. Idelette died of an illness in 1549, and Calvin never remarried. He would remain in Geneva for the rest of his life, publish his major commentaries, revise Institutes, become known as the defender of Christianity, and fully develop the theology that would come to be known as Calvinism.

Five Points of Calvinism (TULIP)

Calvin claimed that God was the source and meaning of one's life as no one simply came to exist from nothing, and so, in recognizing God as the source of one's being, one found true purpose. God had provided people with the means to know this truth, and there was no need for the intermediary measures of the Catholic Church because all one required was the scripture and personal faith to commune directly with the divine. In Chapter 1.1 of the Institutes, he writes:

Our wisdom, in so far as it ought to be deemed true and solid Wisdom, consists almost entirely of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. But as these are connected together by many ties, it is not easy to determine which of the two precedes and gives birth to the other. For, in the first place, no man can survey himself without forthwith turning his thoughts towards the God in whom he lives and moves; because it is perfectly obvious that the endowments which we possess cannot possibly be from ourselves; nay, that our very being is nothing else than subsistence in God alone. In the second place, those blessings which unceasingly distil to us from heaven are like streams conducting us to the fountain. Here, again, the infinitude of good which resides in God becomes more apparent from our poverty. In particular, the miserable ruin into which the revolt of the first man has plunged us, compels us to turn our eyes upwards; not only that while hungry and famishing we may thence ask what we want, but being aroused by fear, may learn humility…Thus, our feeling of ignorance, vanity, want, weakness, in short, depravity and corruption, reminds us that in the Lord, and none but He, dwell the true light of wisdom, solid virtue, exuberant goodness. We are accordingly urged by our own evil things to consider the good things of God; and, indeed, we cannot aspire to Him in earnest until we have begun to be displeased with ourselves.

In this and other passages, Calvin might seem to suggest that all people are capable of recognizing their sinful nature and turning toward God in repentance to secure salvation, but actually, he only believed that those called by God to repent were elected by Him to be saved. The five points of Calvinism have been popularized in the modern era by the acronym TULIP which stands for:

- Total Depravity

- Unconditional Election

- Limited Atonement

- Irresistible Grace

- Perseverance of the Saints

It should be noted that Calvin himself never used TULIP, it is a modern mnemonic device, but the concepts originate with Calvin and inform Calvinist teachings. Total depravity insists on the inherent sinfulness of human beings who are incapable of turning toward God on their own because, after Adam and Eve fell from grace in the Garden of Eden, sin entered the world and governs every aspect of an individual's life.

Unconditional election maintains that only those chosen by God can be saved because all of humanity is spiritually dead in sin and can only be awakened to life by God's will, not by their own. One is predestined by God for either salvation or damnation, and there is nothing one can do to change that. This being so, limited atonement means that not everyone will be saved, only those whom God has chosen, and irresistible grace refers to the power of the Holy Spirit, which lights upon the chosen elect so powerfully that they have no choice but to embrace a relationship with God.

The perseverance of the saints actually refers to the perseverance of God, not those of the elect, to maintain those who are saved. Once one has been called by God, one cannot lose one's salvation, no matter how one behaves, because it is not the individual spirit at work in a person that wins them salvation, but a gift God has chosen to bestow, which He cannot rescind.

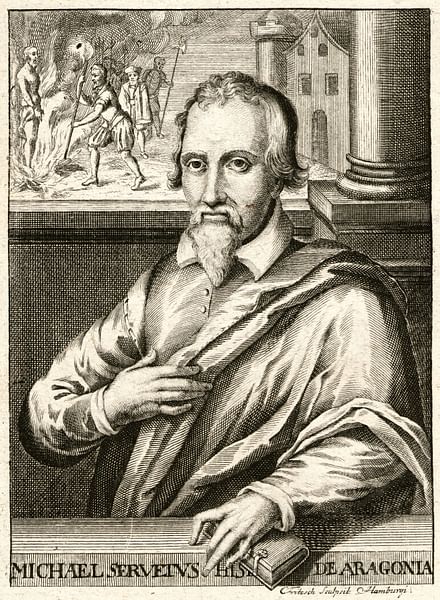

Libertines & Servetus

This gift formed a compact between humanity and God – a covenant – which people were obligated to honor, a concept known as covenant theology, first developed by Bullinger. Since there was nothing one could do to earn salvation, all one could do was live a life reflecting gratitude for that gift through one's works. What one did or did not do had nothing to do with one's salvation; one's works were merely the way in which one honored God's gift, and by living a devout life, one announced one's salvation, even if one could not know if one was, in fact, saved.

Not everyone understood the perseverance of the saints the same way, however. Calvin's claim that salvation could not be lost, gave rise to the movement he called the libertines. The movement was led by upper-class, powerful, citizens of the city who claimed that, since they were saved by God's grace, they could do whatever they wanted without fear of civil or ecclesiastical consequences. When Calvin censured them, they accused him of false teaching, and when he then tendered his resignation, they refused because they felt they could control him better in his present position, and they lacked the support to banish him from the city. Calvin struggled with the libertine opposition for some time on political and ecclesiastical issues until an unexpected event united them.

Calvin reversed his fortunes through the persecution of the Spanish polymath Michael Servetus (l. c. 1509-1553), a scholar who had been corresponding with Calvin and who had criticized The Institutes of the Christian Religion severely, much to Calvin's annoyance. Servetus had been condemned as a heretic in France for denying the Christian trinity and rejecting infant baptism and was fleeing to Italy when he stopped in Geneva to visit Calvin. He was arrested and imprisoned, and afterwards, the libertines and Calvin joined forces in condemning him. Servetus was burned at the stake in Geneva in October 1553.

Calvin's part in the Servetus affair elevated him to the status of 'Defender of the Faith' and won greater support from the city council. When a number of candidates of Calvin's faction won election to the council in 1555, the libertines lost their political power. After they staged a resistance, which civil authorities interpreted as a coup attempt, they were denounced and banished. Calvin supported the proposal to execute any who remained in Geneva, and afterwards, he became the undisputed authority on ecclesiastical matters, which, at that time, influenced civil affairs. From 1555 until his death in 1564, Calvin was the most powerful political and religious figure in Geneva and the best known of all the early Reformers.

Conclusion

Calvin died of an illness at the age of 54 on 27 May 1564. In keeping with his last wishes, he was buried in an unmarked grave to prevent any of his followers from making his tomb a place of pilgrimage as Calvin felt that would encourage idolatry. After his death, his works – already translated into the vernacular of many other countries – spread further and became more popular. While he lived, Bullinger's works were more popular in England, but this now changed, as Calvin's vision, owing much to Luther, Melanchthon, Bullinger, Bucer, and others came to be regarded as the fullest expression of the Protestant vision.

From Geneva, Calvinism spread to the Netherlands, France, England, Italy, and Scotland where it was championed and further developed by John Knox (l. c. 1514-1572). In England, the Calvinists advocated for the use of the Geneva Bible, published in 1560 in Geneva under Calvin's authority. After Calvin's death, leadership passed to the French theologian and scholar Theodore Beza (l. 1519-1605), who maintained, among other aspects of Calvinism, Calvin's claim that the Geneva Bible was the most accurate translation. As the work had been completed and approved under Calvin's authority, it naturally supported his theology. The belief in Calvinism and the Geneva Bible as the true expression of Christianity encouraged the religious dissent of the Puritans and Separatists of England even before the Geneva Bible was translated into English in 1576.

The dissenters rejected the tenets of the Anglican Church and the King James Bible of 1611, claiming that, just like the Catholic Church, these were human contrivances, which separated a believer from direct communion with God. The Separatists would eventually take the Geneva Bible with them to North America in 1621, establishing the Plymouth Colony, and opening up the land to further immigration by other Puritans and Separatists who also adhered to Calvin's theology. From 1621 through c. 1700, Calvinism was the standard by which 'true Christianity' was measured in the so-called New World, and even sects that rejected Calvinist doctrine continued to be influenced by his vision, just as they are in the modern era in their acceptance or rejection of Calvinist tenets.