The House of Burgesses (1619-1776 CE) was the first English representative government in North America, established in July 1619 CE, for the purpose of passing laws and maintaining order in the Jamestown Colony of Virginia and the other settlements that had grown up around it.

A burgess was defined as a freeman and is also given as "citizen", defined at the time as a white male landowner over the age of 21. Although the House of Burgesses is often defined or referenced as the first democratic government in North America, this is inaccurate because:

- Democratic government was already well-developed by the indigenous people and had been in place for over a thousand years.

- The House of Burgesses was not a true democracy because only white land-owning males over the age of 21 were allowed to participate, the governor could veto any law, and all laws were subject to the approval of the Virginia Company of London.

- The Council of State, which advised the governor, was comprised of men appointed by the Virginia Company who had not been elected by their peers or constituency but represented their interests.

It is more accurate to define this assembly as the first English representational government in the North American colonies. Its establishment was encouraged by the English politician Sir Edwin Sandys (pronounced Sands, l. 1561-1629 CE), one of the principal investors and founders of the Virginia Company of London which had funded the expedition to establish Jamestown in 1607 CE. Sandys was an antiroyalist – someone who rejected the concept of the Divine Right of Kings and the monarchy altogether – and supported a governmental structure that was based on the assembly of free men, elected by their peers, to create and uphold laws for the common good.

The House of Burgesses’ first order of business was relations between the colonists and Native Americans, and this would remain an ongoing concern of the assembly in the following years. Although the burgesses continually sought to pass laws and enforce policies they thought fair to both indigenous peoples and immigrants, they failed to recognize that their very presence on lands previously used by Native American tribes was central to all the other problems they tried to address and, further, as more lands were taken for settlements and plantations, land theft was justified by laws, addressing what was thought best for the indigenous people.

The assembly continued to meet as a unicameral political body (meaning a single legislative body) whenever called to order until 1642 CE when it was divided into a bicameral body (two separate legislative assemblies) of the House of Burgesses and the Council of State. These two houses would become more well-defined and autonomous over the years and served as the nexus for opposition to British rule by the colonies in the late 18th century CE.

Many of the Founding Fathers, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry, were members of the House of Burgesses and instrumental in establishing its successor, the General Assembly, comprised of a Senate and a House of Delegates in 1776 CE. A number of scholars in the modern era have argued for the claim that the House of Burgesses, which informed the creation of the United States government, was directly influenced by Native American forms of government, but this claim is consistently challenged.

Native American Democracy

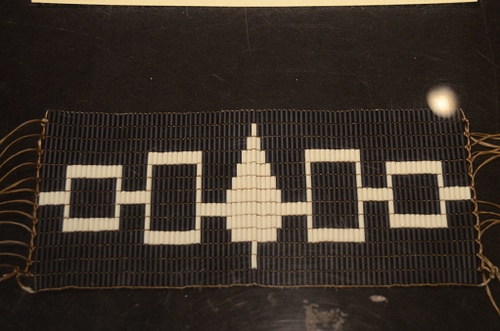

A democratic form of government had been established in North America over a thousand years before the first English colonist set foot on the land. Although many indigenous nations practiced this form of government, it is best documented for the Iroquois Confederacy (also known as the Haudenosaunee) which stretched from modern-day Canada down through North Carolina. The tribes once fought each other in near-constant wars over food and water supplies until the arrival of the Great Peacemaker, Dekanawida, who inspired his two best-known disciples – Hiawatha and, later, Tadodaho – to spread the message of peace and power through unity.

The Cayuga, Kanienkehaka, Mohawks, Oneida, and Seneca first formed the confederacy with the Onondaga and Tuscarora joining later. Scholar David J. Silverman describes the form of government, known as a League, established c. 1000 CE though existing in some form long before that time through tribal councils:

Like the tribal councils, League meetings of clan sachems [chiefs] focused not on policymaking but peacekeeping, specifically a halt to the cycles of revenge warfare. (42)

At the same time, however, the League did, in fact, make policy as a means toward keeping the peace. The clan chiefs were chosen by the matrons of their clan on the basis of their eloquence and ability to represent the interests of their people. Although members of the tribe did not directly elect their representatives, they trusted the matrons who chose them, and those chosen who did not faithfully represent the interests of their clan were removed and replaced by others. Discussion of policy was encouraged, and debate was integral to any decision on laws, the acceptance of which had to be agreed upon unanimously. The Iroquois thereby instituted a unicameral legislative body in North America centuries before the English arrived.

Virginia Company, Jamestown, & Tobacco

Other tribes, from modern-day New England down through Virginia, implemented similar forms of government and were fully operational when England began its efforts to colonize the so-called New World of North America. The Virginia Company of London funded the 1607 CE expedition which established Jamestown in the marshes of Virginia on land which had been rejected as unsuitable by the Powhatan Confederacy of the region. The settlement struggled to survive and only did so once Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) took control, stopped the colonists from stealing from the natives, forced them to work the land for their food, and formed an alliance with the Powhatan chief Wahunsenacah (l. c. 1547 - c. 1618 CE).

Smith left the colony to return to England in the fall of 1609 CE, and relations deteriorated between the colonists and indigenous people. The colony suffered through what is now known as the Starving Time during the winter of 1609-1610 CE and, in May of 1610 CE, a ship brought the man who would turn Jamestown’s fortunes around; John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622 CE). Rolfe arrived with tobacco seeds he had somehow acquired and thought would do well in the Virginia soil. He was correct and, by 1614 CE, had already harvested his first very profitable crop, which encouraged others to begin planting tobacco.

The expansion of Jamestown, as well as the neediness of the colonists and their tendency to steal from the natives, had resulted in the First Powhatan War (1610-1614 CE) which ended when Rolfe married the daughter of Wahunsenacah, Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617 CE), establishing the Peace of Pocahontas in 1614 CE. Other settlements, such as Henricus, had been founded by this time, and more land was purchased (or taken) from the natives for tobacco plantations and settlements. Pocahontas died in 1617 CE, and tensions began to mount between the colonists and natives who saw more of their land taken, and more of their crops appropriated, without compensation.

House of Burgesses Established

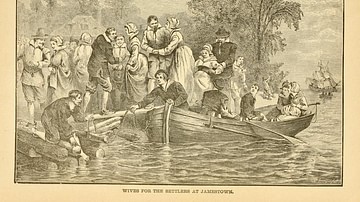

At this point in the colony’s development, Sir Edwin Sandys (who was also responsible for the Jamestown Brides program) recognized the need for an on-site representational government to direct affairs in North America. From the beginning, Jamestown had been led by a colonial governor appointed by the Virginia Company who made decisions, sometimes, after consulting with advisors. Sandys encouraged the establishment of a legislative body that would be better able to address the needs of an expanding colony and meet the challenges posed by the resistance of the indigenous people to their loss of land rights. Scholar David A. Price describes the original organization of the legislature in July 1619 CE:

No account of the rules of suffrage in 1619 Virginia has survived, but it is safe to assume they followed the practice of the mother country in excluding male indentured servants (because they were not property owners) as well as all women. The voters of each city, borough, and plantation elected two “burgesses” to represent them. There were seven plantations by mid-1619, so the burgesses included eight men from the cities and boroughs and fourteen from the plantations, or twenty-two men all together. The assembly resembled the modern U.S. Senate in that its burgesses represented a wildly variable number of constituents. (190)

Initially, participation in the assembly was limited to English male property owners, but when Polish artisans and craftsmen learned of this, they went on strike and refused to work until they were given full rights in participatory government. The first session of the assembly met on 30 July 1619 CE in the Jamestown church and was presided over by the governor Sir George Yeardley (l. 1587-1627 CE). The Speaker of the House was John Pory (1572-1636 CE) who was responsible for establishing the parliamentary procedures which would govern meetings and are still in use in the present day.

The session was opened with a prayer offered by the Anglican priest Richard Buck who had arrived in the colony with Yeardley and Rolfe in 1610 CE and, after the prayer concluded, Pory presented the assembly with the first item on the agenda: a complaint made against plantation owner John Martin for taking corn by force from a group of Powhatans who had refused to sell to him. Colonists were called as witnesses to the event and the charges were discussed. Price comments on the nature of the assembly:

The new body was not a pure representative democracy by any means. Apart from the qualifications on suffrage, the democratic charter of the assembly was slightly diluted by the fact that it included not only the burgesses, but also the governor's "Council of State", a half dozen men appointed by the company to serve as the governor’s advisers. These men were themselves colonists, and were charged with representing the colonists' interests, but they had not been elected by anyone. The governor held a power of veto (a "negative voice"), as did the company's council in London. (190)

By unanimous vote, Martin was censured and ordered to appear before the legislature to give his side of the story. He was ordered to remit a certain amount to the assembly as security that neither he nor his people would molest the indigenous tribes or touch their property without consent in the future. He was not required, however, to seek permission from the governor for trade with natives which established policies regarding personal property in the colonies. A provision was then passed, the first, protecting the rights of the natives to their land, selves, and property. The assembly then moved on to other business but adjourned prematurely due to the extreme heat of early August in the close quarters of the church.

Slavery, Expansion, & Powhatan Wars

The sale of tobacco crops had not only saved Jamestown but made it rich, and this encouraged the arrival of more colonists – whether as landowners or indentured servants – who wanted to make their fortune on the crop as well. The same year that saw the establishment of the House of Burgesses brought the first Africans to the colony, 20 of whom were bought by Sir George Yeardley, making him Virginia’s first slave owner.

Some scholars (Price among them) question whether these first Africans were treated as slaves and argue they were considered more along the lines of indentured servants. Evidence does suggest the presence of free blacks in colonial Jamestown and certainly, by 1676 CE, there were black landowners and at least one on record as owning black slaves himself. Even if the Africans were not treated as slaves, however, they arrived in that condition aboard a Dutch ship, which had captured them as cargo from a Spanish trader. Slavery would not become institutionalized in Virginia until the 1660s CE but the first African slaves can be said to have arrived in the colony in 1619 CE.

Yeardley put his new slaves (or servants) to work in the tobacco fields, his own being only one among the many which were expanding further into Native American lands. The more colonists arrived, the more land was required for settlements, farms, and tobacco plantations, and the Powhatan Confederacy finally had enough. Wahunsenacah had been succeeded by his half-brother Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646 CE) who, in 1622 CE, launched what came to be known as the Indian Massacre of 1622 and the start of the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626 CE), killing over 300 colonists. The House of Burgesses passed legislation organizing the militia of the settlements and the establishment of defenses.

The legislators would do the same later during the Third Powhatan War (1644-1646 CE) and again after Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 CE. After this event, during which indentured servants had participated in a revolt led by landowner Nathaniel Bacon (l. 1647-1676 CE), the House of Burgesses recognized the danger of continuing to import indentured servants who would be rewarded, once they completed the terms of their service, with land which equaled political power. Indentured servitude was discontinued, and slavery was further institutionalized to continue harvesting the tobacco crop. Although the first order of business of the House of Burgesses had been the protection of Native American rights and property, this legislation was forgotten as profits from tobacco sales increased and more land was required for plantations.

Conclusion

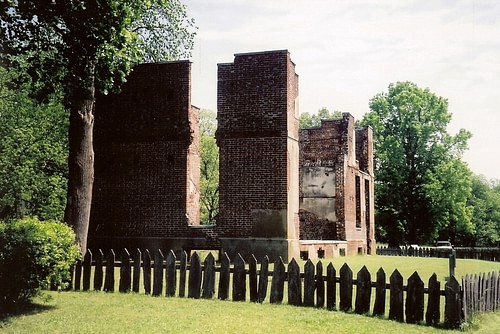

The Virginia Company was dissolved in 1624 CE, and the English government took direct control of the North American colonies. The House of Burgesses, however, continued to meet and pass legislation in accordance with the policies of the English government. In 1634 CE the assembly divided the ever-expanding colony into counties and reorganized representation, and the assembly was changed to a bicameral body in 1642 CE of the House of Burgesses and the Council of State. In 1676 CE, during Bacon’s Rebellion, Jamestown was burned and the government moved to the area of Middle Plantation, later known as Williamsburg.

England’s Seven Years’ War (1756-1763 CE) with France (known as the French and Indian War in its North American theater, 1754-1763 CE), was costly and resulted in higher taxation of the colonies and disruption of colonial trade. English legislation concerning trade, colonial economy, and political autonomy followed throughout the 1760s CE, increasing tension between the crown and the colonies. The House of Burgesses, by this time, had a long history and inspired similar legislative bodies elsewhere.

The colonies of New England had also established their own colonial governments and, increasingly, saw no need to obey the dictates of the English government. Tensions grew in the early 1770s CE, finally leading to the outbreak of hostilities in 1775 CE and the American War of Independence (1775-1783 CE). Price comments:

The establishment of the General Assembly in 1619 and the introduction of broad-based property ownership the same year were critical milestones on the path to American liberty and self-government. It is hard to overstate their lasting effect on American political culture, as the bases for the eventual spread of private property and representative government in the English colonies. (194)

The House of Burgesses was dissolved on 6 May 1776 CE. It was never officially adjourned and became the General Assembly consisting of the House of Delegates and the Senate of the Commonwealth of Virginia, declaring its independence from Britain. Members of the House of Burgesses would play pivotal roles in the War of Independence and the founding of the United States’ government afterwards.

One of the Founding Fathers, Thomas Paine (l. 1737-1809 CE), though not a member of the House of Burgesses, is often referred to as the "Father of the Revolution" for his Common Sense and The American Crisis, which provided the philosophical justification and inspiration for the war. Paine became a controversial figure in his own time for arguing that the government of the Iroquois Confederacy should be the model for that of the United States. According to some modern scholars, it was, but just as in Paine’s time, this claim is challenged, and the subject is often omitted from the narrative of the founding of the United States.