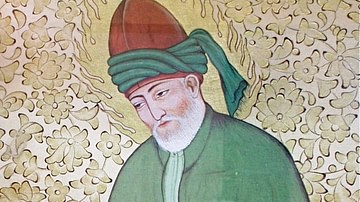

Hafez of Shiraz (also given as Hafiz, l. 1315-1390) is considered the greatest of the Persian poets and among the most famous and admired writers in world literature. He is among the most often translated poets in the present day and his work continues to resonate with modern audiences.

His full name is Khwaja Shams-ud-Din Muhammed Hafez-e Shiraz, but he was known as Hafez (which means “memorizer”) because he memorized the Quran at an early age and would later memorize the works of other Persian poets such as Sanai (l. 1080 - c. 1131), Attar (l. 1145 - c. 1220), Rumi (l. 1207-1273), Saadi (l. 1210 - c. 1291), and Nizami (l. c. 1141-1209), all of whom would influence his own work.

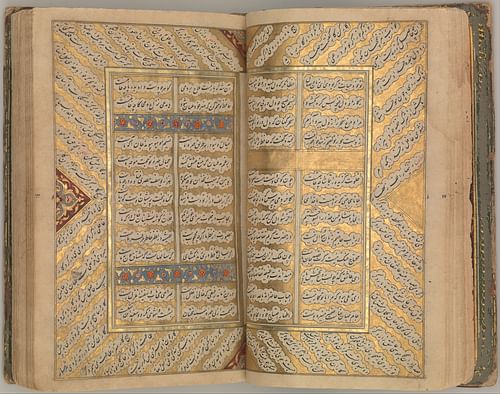

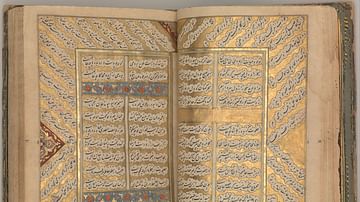

Little is known of his personal life except that he was born in Shiraz (in modern-day Iran) and his parents were from Fars. He was well educated and most likely had connections to the ruling house as he spent his life as the court poet to the region's monarchs. He was a Sunni Muslim and a devotee of the mystical approach to Islam known as Sufism which informs his poetry along with Quranic literature, Persian legend and myth from the Shahnameh, and various other sources. Unlike other poets (such as Rumi) there is no definitive collection of his works. His divan (a collection of short pieces) was compiled by others but scholars do not agree on when or even by whom.

Hafez's poetry focuses on the transcendent power of love and the transformative effects of opening one's self up to all experience through embracing what it means to be a human being in the fullest sense which, to Hafez, includes an intimate relationship with God. His work is described by many scholars as antinomian, meaning a rejection of rules, regulations, and strictures, and this label is apt as Hafez considered life too large to be contained and dictated by small labels and narrow commandments. His many allusions to wine, drunkenness, taverns, and abandonment to sensual desire attest to this, although, as many scholars have noted, Hafez's poetry can be read on many levels and these allusions may also be understood as allegorical references to the experience of Divine Love.

Hafez would become the most popular and well-respected poet of his day and his reputation for piercing mystical insight and beauty of composition still holds in the present day. His mausoleum in Shiraz, surrounded by gardens and small waterfalls, attracts admirers from around the world who not only continue to respond to his written works but claim a mystical communion with the poet in their daily lives.

Early Life & Influences

Hafez was born in Shiraz to Sunni Muslim parents about whom nothing is known. His father may have been an imam (a religious leader) since Hafez is said to have memorized the Quran by listening to his father recite it repeatedly, one of the responsibilities of an imam. Shiraz was a cosmopolitan and refined cultural center, praised by the famous travel writer Ibn Battuta (l. 1304-1368/69) for its beauty and inspirational power, which encouraged artistic, intellectual, and religious developments. Scholar Leonard Lewisohn comments:

This city of Saints and Poets…was especially famous for its colleges and seminaries, its Sufi centers and mosques, many of which had large accompanying gardens and possessed properties attached by charitable bequest to their grounds. The presence of these institutions…lent the town a peculiar sacred ambience in the popular imagination. (3)

The era in which Hafez lived was a turbulent time in Iran. The Mongols had invaded the region one hundred years before Hafez was born, establishing dynastic houses which were not always popular, and conflicts between various ruling houses – or within them – were ongoing. Sufism, with its emphasis on individual liberation regardless of external circumstance, would have had great appeal during such a time. Sufism is not a sect of Islam but a mystical experience based on an Islamic worldview, which seeks to transcend any perceived artificial strictures. Scholars John Heath-Stubbs and Peter Avery comment:

The tendency of Sufism is pantheistic. Each human soul is a particle of the divine Absolute, and the mystic aims at a complete union with the Divine. This union is attained in the knowledge that he is himself that ultimate Reality which he seeks. But the individual self is completely annihilated in this higher self, like the moth drawn to the candle-flame. For the sake of the esoteric knowledge, the Sufi must abandon all, in particular the legalistic restraints of conventional religion. (5)

How Hafez was introduced to Sufism is unknown but Shiraz at this time was a Sufi center so he could have easily absorbed the concepts without any effort (though he is said to have later studied with the Sufi master Zayn Attar, d. 1403). He may have worked as a draper when he was young before being employed as a delivery boy for a bakery. On one of his deliveries, he is said to have seen the beautiful upper-class woman Shakh-e Nabat, and knowing he could never have an actual relationship with her, attempted a spiritual union through meditation.

Hafez the Court Poet

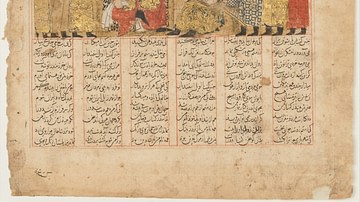

Sufism was not the only major influence on Hafez's work, however, as it was also molded and shaped by his position as court poet, first under the Inju Dynasty (1335-1357) and then under the Muzaffarid Dynasty (1314 - c. 1393). The Inju Dynasty was among those founded by the Mongols and Hafez may have first worked for the ruling house as court poet under Saraf-al-Din-Mahmud c. 1339. He was definitely a poet of note by the time of the reign of Jamal al-Din Abu Ishaq (c. 1343-1357) for whom he wrote a number of verses.

The court poet was considered essential to the function of the government as an adviser and confidante as well as musician, composer, and all-around entertainer. The poet's ultimate goal was to immortalize the monarch through verse and this was accomplished, over time, through poems praising the king for various aspects of his reign, his mercy, piety, military prowess, or physical beauty. Scholar Sassan Tabatabai comments:

Traditionally, the court poet, whose function went far beyond that of a mere entertainer, was an integral part of the Persian court. Ardashir Babakan, the founder of the Sassanian dynasty in the third century, considered the poet “a part of government and the means of strengthening rulership.” (3)

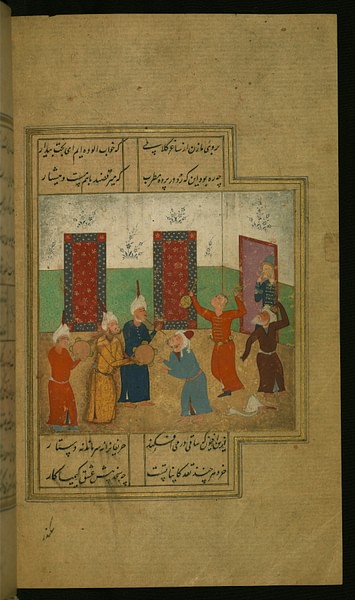

The court poet was supposed to be able to compose extemporaneously and would accompany himself on a musical instrument. A verse or couplet would be recited and the poet would then play a short musical interlude (ostensibly while he composed the next verse) and then continue. These poems lavished praise on the king who is often addressed, and described, in terms and images equally applicable to the Divine or a loved one. Heath-Stubbs and Avery write:

The enumeration of the beloved's charms and the complaints of his cruelty, which also described the Divine Beauty, or the soul's grief at separation from it, are further to be read as compliments to a princely patron's magnificence, or respectful reproaches to him for his tardiness in rewarding his poet's services…It must be remembered that the princes who, together with their ministers, were the subjects of Hafez's verse, were absolute rulers. They could claim, in some sort, to be God's vice-regents on earth, and the splendor of their own courts was an image of the glory which is on high. (10)

Around 1357/1358, the Inju fell to the Muzaffarids under Mubariz al-Din Mohammaed whose cruelty encouraged his son, Shah Shuja Mozzaffarir (r. 1358-1384) to overthrow, blind, and imprison him. Hafez continued as court poet under Shah Shuja, for whom he would write most of the verses which, today, are interpreted as addressing God.

The Religion of Love & Hafez's Works

These poems, with their soaring praises of the beloved and his graces, contribute to what modern-day scholars often reference as the Religion of Love embraced and preached by Hafez. The Religion of Love knows no rules and follows no guidelines but the precepts of the heart. Hafez's poem 38, as translated by Gertrude Bell, reads, in part:

I cease not from desire till my desire

is satisfied; or let my mouth attain

My love's red mouth, or let my soul expire,

Sighed from those lips that sought her lips in vain.

Others may find another love as fair;

Upon her threshold I have laid my head,

The dust shall cover me, still lying there,

When from my body life and love have fled…

When I am dead, open my grave and see

The cloud of smoke that rises round thy feet;

In my dead heart the fire still burns for thee;

Yea, the smoke rises from my winding sheet!

Ah, come, Beloved! For the meadows wait

Thy coming, and the thorn bears flowers instead

Of thorns, the cypress fruit, and desolate

Bare winter from before thy steps has fled. (The Poetry of Hafiz of Shiraz, 5)

This poem, like many others, is often interpreted today as a “love poem” in which a lover addresses his mortal beloved but, as Heath-Stubbs and Avery point out, “Almost any poem of Hafez's can, in fact, be read on at least three levels of significance” (9). The speaker in this translation is addressing a woman but, in the original, could be speaking to the poet's patron, a young man, or God. Erotic symbolism is frequently used to express spiritual desire just as Hafez's use of the image of wine or experience of drunkenness stands for the intoxicating nature of one's relationship with God. Heath-Stubbs and Avery write:

The images of Hafez's poetry are to be taken as applicable to the universal experiences of the mystic. The beloved becomes the Divine Lover; separation from Him, in its various degrees, is the Dark Night of the Soul, union with Him the mystic's ecstatic absorption in the absolute. (9)

At the same time, the poem can be understood on a literal level as an expression of romantic love and sexual desire. Persian poetry frequently was addressed to young men, at least on a surface level, as embodying divine beauty because young men were encountered at court far more frequently than women who, according to Islamic tradition, were sequestered. Although scholars have interpreted the verses of various Persian poets along homo-erotic lines, the works are better understood as expressions of what Plato would call the “form of beauty” – a divine Absolute reflected in something or someone on the physical plane. A love poem by a man to a man, therefore, does not necessarily mean a romantic or sexual attraction of one for the other. The poet is simply recognizing the nature of beauty in a physical form; the particular form is not important.

Preachers who display their piety in prayer and pulpit

behave differently when they're alone.

It puzzles me. Ask the learned ones of the assembly:

“Why do those who demand repentance do so little of it?”

It's as if they don't believe in the Day of Judgment

with all this fraud and counterfeit they do in His name.

I am the slave of the tavern-master, whose dervishes,

in needing nothing, make treasure seem like dust.

O Lord, put these nouveaux-riches back on their asses

because they flaunt their mules and Turkic slaves.

O angel, say praises at the door of love's tavern,

for inside they ferment the essence of Adam.

Whenever his limitless beauty kills a lover

others spring up, with love, from the invisible world.

O beggar at the cloister door, come to the monastery of the Magi,

for the water they give makes hearts rich.

Empty your house, O heart, so that it may become home to the beloved,

for the heart of the shallow ones is an army camp.

At dawn a clamor came from the throne of heaven.

Reason said, “It seems the angels are memorizing Hafez's verse.”

(The Poetry of Hafiz Shiraz, 7)

This poem may also be read on a number of levels. On the literal level, it is a charge against religious hypocrisy and a call to abandon the restrictions of man-made religion for the freedom of experience in the tavern and the exploration of the desires of one's heart. The image of the “monastery of the Magi” is a reference to a colloquial expression of Hafez's time in which “magi” or “Magian” meant wine-seller or purveyor of alcohol. Since the sale and use of alcohol was prohibited by Islam, only Jews and Christians could sell wine or operate taverns. The magi were the priestly class of the pre-Islamic Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, who encouraged intoxicants as part of the spiritual experience, and so wine-sellers of Hafez's time were “honorary magi” and a tavern a “Magian Temple” or “monastery”.

On another level, however, the poem expresses the heart of Sufism in which the “tavern-master” is God who encourages those who love Him to ignore the hypocrisy and deceit of mainstream clergy to seek an honest relationship with the Divine through their own efforts. In either reading, the poet congratulates himself on his views by claiming that even the angels approve and memorize Hafez's poetry just as he once memorized the Quran.

Modern Veneration & Interpretation

Hafez's works, like those of any poet, lose something vital in translation but, in his case, the loss is more significant in that the original Persian is so nuanced and one word can have multiple meanings. His poetry, in the original, could be interpreted quite differently by anyone who read or heard it recited according to their own beliefs. This freedom of interpretation contributed to Hafez's status as the most popular poet of his day.

It is a testament to his popularity and skill with words that even the ruthless conqueror Timur (better known as Tamerlane, r. 1370-1405) read Hafez and even upbraided the poet for one of his lines. According to the story, Hafez responded so cleverly to this criticism that Timur rewarded him handsomely. Even though Hafez strongly disapproved of Timur's 1387 conquest, indiscriminate massacres, and the taking of Shiraz, and the two men had nothing in common, even Timur could find something in Hafez's work to respond to.

People in the modern day continue to respond to Hafez's poetry, all around the world, and he remains a bestselling poet. Many of the so-called “translations” of his work today are not translations at all but a modern poet's “channeling” of his spirit to create Hafez-inspired poems. The best example of this is the poet Daniel Ladinsky in his The Gift: Poems by Hafiz the Great Sufi Master which are poems Ladinsky claims came to him in a dream in which Hafez "sang hundreds of lines of his poetry to me in English, asking me to give that message to my 'artists and seekers'" (Mansfield, 2).

A popular poem found online such as Now is the Time, consistently attributed to Hafez, should therefore more properly be attributed to Ladinsky-channeling-Hafez. Ladinsky is hardly the first to make such a claim. Many people who visit Hafez's mausoleum in Shiraz claim to receive messages and guidance from the poet and his association with the Divine encourages fortune-tellers at the site to offer their services, claiming Hafez's spirit guides them.

The tradition of Hafez-inspired poetry, however, goes back much further to the German poet Goethe (l. 1749-1832) and his West-Eastern Divan, a collection of poems written in the spirit of Hafez. The pseudo-translation of Persian works is most famous through the work of the English poet Edward Fitzgerald (l. 1809-1883) whose Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam became a bestseller in the West in the late 19th and throughout the 20th century. Fitzgerald did not “translate” Khayyam's work so much as “interpret” it according to Fitzgerald's own sensibilities. That tradition is continued today by scholars such as Coleman Barks in his works on Rumi, but none of these went as far as Ladinsky with the claim to be in present communion with Hafez.

Whether Ladinsky or others hear from Hafez or do not, however, would not trouble the poet himself and he would certainly approve of the joy his "new works" bring to people as well as the messages they claim to receive at his tomb. During his life, his poetry was interpreted by diverse people according to their beliefs and needs and so it has been since his death. He is regarded, along with Ferdowsi and Rumi, as one of the three foundational poets of Iran but no one country can contain Hafez anymore than any one religion or language. Hafez's vision of universal friendship, experience, and communion with the Divine crosses all boundaries and ignores all divisions, welcoming all who respond to his Religion of Love.