Abolqasem Ferdowsi (l. c. 940-1020 CE, also given as Abul-Qasem Ferdowsi Tusi, Firdawsi, Firdausi) is the author of the Shahnameh (The Persian Book of Kings), one of the greatest works of world literature and the national epic of Iran. He is considered among the most important poets writing under the Samanid Dynasty (819-999 CE) and succeeding Ghaznavid Dynasty (977-1186 CE).

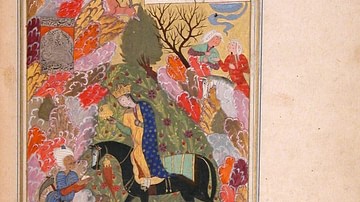

Ferdowsi (whose name means “from paradise”, generally interpreted as “man from paradise”) began the Shahnameh after his contemporary, the poet Daqiqi (l. c. 935-977 CE), who had begun a version, was murdered by a slave. The work, commissioned by the Samanids, was an ambitious venture, telling the story of Persian history from the beginning of the world to the fall of the Sassanian Empire in 651 CE to the Muslim Arabs. Persian culture had been suppressed afterwards but, under the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE), revived and was fully embraced and encouraged by the Samanids.

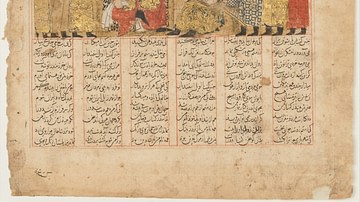

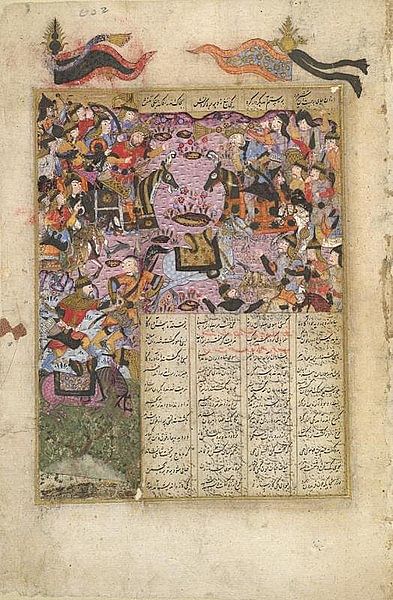

The Shahnameh is Ferdowsi's life's work, written between 977-1010 CE and comprised of 50,000 rhymed couplets of verse. How it was received by the Ghaznavids upon completion is a matter of some debate even though it is established that the Ghaznavids did not have the same appreciation for Persian culture as the Samanids had. It is reported by the poet Nezami-ye Aruzi (wrote c. 1110-1161 CE), that Ferdowsi was treated poorly by his Ghaznavid patron; a claim Ferdowsi himself makes toward the end of his poem and so is generally accepted. Ferdowsi fully understood the significance of what he had accomplished, even if he was not paid what he deserved, and claimed his name would live forever through his work; this has proven true as he remains one of the best-known and highly-respected poets of world literature.

Persian Literature & the Muslim Arab Conquest

To appreciate Ferdowsi's commitment to his work, one must understand the historical and cultural background which informed his life. Scholar Dick Davis comments:

Although there can be no doubt whatsoever that Ferdowsi was a sincere Moslem…he makes no attempt to include any elements of the Qur'anic/Moslem cosmology in his poem, nor does he attempt to integrate the legendary Persian chronology of the material at the opening of his poem with a Qur'anic chronology. Unlike other writers who dealt with similar material, and who did attempt to intertwine the two chronologies, he simply ignores Islamic cosmology and chronology altogether and places the Persian creation myths center stage. (xix-xx)

Ferdowsi chose this focus because his objective in writing the work was the preservation of a past that had almost been lost through conquest. It is probable that he would have written the work, without any promise of payment, in order to create a literary landscape that would provide access forever, to anyone who opened his book, on what it meant to be Persian and the importance of remembering and honoring one's past.

Literature developed from the reign of the first Sassanian monarch, Ardashir I (224-240 CE) to the last, Yazdegerd III (r. 632-651 CE) when the empire fell to the Muslim Arabs. The conquerors destroyed libraries, temples, and texts in an effort to subjugate the people and those works which were not hidden, or carried out of the region, were lost. The Khodaynamag, it seems, was among those preserved (along with the Avesta, various commentaries, and some other works) but this would have been small comfort in the face of such catastrophic loss of so many books. Davis notes:

The Arab conquest of the seventh century CE came as an overwhelming shock, especially since it must have seemed for a while as though Persian civilization would disappear as an entity distinguishable from the culture of other countries subsumed into the Caliphate. An Iranian scholar has dubbed the numbed aftermath of the conquest in Iran as “the two centuries of silence” …The Umayyad dynasty (661-750) had scant regard for Persian civilization and sensibilities and treated even converts to Islam as second-class citizens if they were not of Arab stock. (xvii)

This situation began to change when the Abbasids came to power. In order to overthrow the Umayyad Caliphate, the Abbasid Dynasty enlisted the aid of the Persians whose status rose considerably afterwards. The ruling house was linked by blood to the Persians, Persian was spoken at court and, in time, an interest in Persian culture encouraged a resurgence of Persian literary efforts, especially of poetry.

Revival Under the Samanids

Poetry was always the language of Persian works, no matter what the subject matter, as later texts on science, medicine, mathematics, history, and religious commentary – as well as the Avesta itself – attest. The poetic form, however, what one would recognize as a poetic composition, was considered the highest form of expression and found favor with the monarchs of the Samanid Dynasty who reigned with Abbasid permission.

The first great poet of this period was Rudaki (l. 859 - c. 940 CE), considered “the father of Persian literature”, who became famous – and wealthy – as the court poet of the Amir Nasr II (r. 914-943 CE). Although Rudaki is most closely associated with this monarch, and some sources claim he was brought to court only during Nasr II's reign, his extant work shows he was already court poet under Nasr II's father, the Amir Ahmad Samani (r. 907-914 CE), for whom he composed an elegy on the death of Ahmad's father.

Traditionally, the court poet, whose function went far beyond that of a mere entertainer, was an integral part of the Persian court. Ardashir Babakan, the founder of the Sassanian dynasty in the third century, considered the poet “a part of government and the means of strengthening rulership.” Other than praising the ruler and his realm, the poet was expected to be a source of counsel and moral guidance. As such, a poet like Rudaki would have to be well-versed in tradition. He would have to be familiar with the body of didactic literature of the past and draw upon it when necessary. (3)

Rudaki's success at court was followed later by the poet Daqiqi at the court of the Amir Mansur I (r. 961-976 CE). Little is known of Daqiqi's life and work, but he must have been a poet of note to retain a position at the Amir's court. He is primarily known for his attempt to draw on the vast oral tradition of the past, and those works which had survived the Muslim Arab conquest, to create a great national epic at the request of his patron. Daqiqi used the Khodaynamag and another prose work (The Book of Kings of Abu Mansur) as his primary sources and had composed 1,000 verses before he was murdered by his slave.

Ferdowsi's Life & the Shahnameh

His work was taken up by Ferdowsi who seems to have begun shortly after Daqiqi's death. Ferdowsi came from the upper-class land-owning elite known as the dehqan. The designation of dehqan carried significant prestige as it was almost synonymous with “true Persian”. This status, and his skill as a poet, would have recommended him for the job of completing Daqiqi's work but he was also well-educated and a friend of the aristocrat Abu Mansur Muhammed (d. 987 CE), who had commissioned the earlier prose Book of Kings.

Scholar Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh notes how, “Up to this time, the poet must have produced poetry which has since been lost” (Encyclopedia Iranica, Ferdowsi, 5). This is no doubt true as Ferdowsi would have had to have been able to demonstrate some skill before he was accepted as Daqiqi's successor. In keeping with Tabatabai's observations concerning the court poet's need to be steeped in tradition and to be able to draw on the literature of the past, Ferdowsi would have been an obvious choice even though there is no evidence he was Mansur I's, or Abu Mansur's, court poet.

According to Ferdowsi's own account, given at the end of the work, he was never paid what was promised. He writes:

Nobles and great men wrote down what I had written without paying me: I watched them from a distance, as if I were a hired servant of theirs. I had nothing from them but their congratulations; my gall bladder was ready to burst with their congratulations! Their purses of hoarded coins remained closed, and my bright heart grew weary at their stinginess. (Davis, 962)

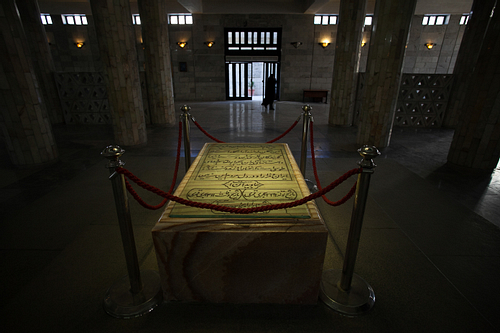

Other details of the poet's life come from Nezami-ye Aruzi who visited Ferdowsi's tomb c. 1116 CE and recorded the stories told of him. According to Nezami, it took Ferdowsi thirty years to write the Shahnameh and, when the work was completed, the sultan agreed to pay him the sum of 60,000 gold pieces. The courier entrusted with the delivery, however, was a Sunni Muslim and despised Ferdowsi for his Shia sympathies and so changed the gold coins for silver. He delivered them to Ferdowsi at a bathhouse and, when the poet found he had been paid in silver instead of the agreed upon gold, he bought himself a beer from a stand outside and then gave half the silver to the beer-seller and half to the keeper of the baths and then left the region. Another version of this same story has the sultan complicit in replacing the gold with silver for the same reason.

Ferdowsi feared he would be punished for refusing the sultan's gesture and moved from place to place to avoid what he considered his certain arrest and probable execution. He found refuge at the court of the monarch Sepahbad Shahreyar where, in retaliation for his ill-treatment, he composed a satire of Mahmud which he added to the preface of Shahnameh, read to Shahreyar, and offered to dedicate the piece to him instead of Mahmud. Shahreyar paid him for his efforts in writing the satire, took the piece, and had it removed from the Shahnameh. The satirical section is claimed to still exist in the present day but its authenticity has been challenged.

According to Khaleghi-Motlagh, however, the sultan Mahmud sent only 20,000 dinars to Ferdowsi, regretting his earlier behavior but, as with the legendary account, the payment arrived too late. Khaleghi-Motlagh comments:

Ferdowsi left only one daughter, and the poet had wanted the king's payment as a dowry for her. But after the poet's death, his daughter would not accept the payment and, on Mahmud's orders, the money was used to build the Caha caravansary at Tus, on the road which goes from Nishapur to Marv. (Encyclopedia Iranica, Ferdowsi, 6)

Whatever details of the end of the poet's life may be true, the general impression from the earliest sources is that Ferdowsi died feeling he had been poorly used by those he had most relied on, was in declining health long before the heart attack, and was most likely living off the revenue of his family's lands, especially the orchard where he would be buried. Ferdowsi himself, however, claims at the end of his work that, no matter what may happen to him, his name would live on through the Shahnameh.

Conclusion

His belief in the value of the work was justified in that it has not only been read and admired now for centuries but accomplished one of Ferdowsi's primary goals: the preservation of Persian history, lore, and language. There are a number of lines in the Shahnameh which make clear how resentful the author was toward those who had tried to destroy his culture. The Shahnameh was his answer to any future attempts to do the same. Davis writes:

Whatever else it is, the Shahnameh is the one indisputably great surviving cultural artifact that attempts to assert a continuity of collective memory across the moment of the conquest; at the least, it salvaged the pre-conquest legendary history of Iran and made it available to the Iranian people as a memorial of a great and distinctive civilization. (xxxiii)

The Shahnameh has so informed Iranian culture up to the present day that scholars, including Davis, credit it with preserving the Persian language intact. Modern Persian retains the essential form of Ferdowsi's time and this is largely credited to his work which became standard reading in the Iranian educational system.

Although the Shahnameh has fallen out of favor during various regimes throughout the country's history, interest in it is always revived and the work remains popular, not only in Iran but around the world, for the same reason any great piece of literature endures: because in telling the truth about the struggles and triumphs of one people, the author touches on the same for all.