Caesarea Maritima was a city built over 2,000 years ago (c. 22-10 BCE) on the coast of the Eastern Mediterranean. With Roman engineering and largesse, Herod the Great (r. 37-4 BCE) accomplished this feat by constructing a whole metropolis with a colossal harbor that would make Caesarea the maritime trading oasis of its day.

Early History

Dedicating the city to Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE), the area on which Herod chose to build began as a locale of habitation by the Phoenician city-state of Sidon. Specializing in glass products, and embroidered garments, and famous for its purple-dyed cloth, Sidon may have realized the location's potential in relation to trade with the East and the greater Mediterranean nations. Presumably named after King Straton I (r. 365-352 BCE) of Sidon, the place was known as Straton's Tower. North of Egypt and equidistant between Gaza and Sidon (120 km either way), it lay in the midst of shipping and trade routes.

Of the descriptive name given it by Flavius Josephus (36-100 CE) and other ancient writers, it is not known if Straton's "Tower" indicates a lighthouse, a warehouse, or perhaps a grain silo since Sidon shipped raw goods and Straton's Tower was en route "the long-established Phoenician-Egyptian run" (Bull, 26). Interestingly, silos recently found in Egypt, dating to around 1600 BCE, are up to 6.5 meters (21 ft) in diameter, suggesting a conspicuous degree of height. Either way, as Straton's Tower was known to be a trading village, Strabo (c. 63 BCE to 24 CE) also reports it had its own "station for vessels" (16.2.27).

Once providing ships and goods for the Persian Empire, Sidon's certain nadir began, alongside Persia's defeat by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. Soon after Alexander's death, one of his generals, Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE), began the Greek Seleucid takeover of former territories of the Achaemenid Empire, including Phoenicia. Today, from the ruins of Caesarea, excavators have found Hellenistic pottery and coins that date from the last two centuries BCE. Additionally, evidence of a pre-Herodian fortification associated with a Hellenistic presence is dated to the same time period. Such discoveries suggest a relatively brief presence of the Seleucid Empire at Straton's Tower. The area was then captured by the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus in 103 BCE. During the late Roman Republic, Pompey the Great (106-48 BCE) attached it to the province of Syria, and then Octavian gave it to Herod in 30 BCE.

Herod's City

Built on the area's ruins, after its inauguration and dedication to Augustus by Herod in 13/12 BCE, Caesarea became a cosmopolitan city of Jews, Christians, Samaritans, Greeks, and Syrians living in their own districts. Within its original walls, the city contained 164 acres, but during the time of the Pax Romana – when Roman legions on the borders of the Roman Empire made a protective wall unnecessary – the city expanded far beyond the original Herodian wall. With an urban sprawl 8 kilometers (5 mi) long and over 3 kilometers (2 mi) inland, Caesarea, at its height, became home to an estimated quarter million residents.

While we normally think of city growth in terms of incremental expansion and development, it is remarkable that the infrastructure of Caesarea Maritima was built ready for habitation. Yet, as Herod was known to do with all his monumental building programs, the buildout at Caesarea was not done on the cheap. Flavius Josephus (36-100 CE), a reliable historian and eyewitness of the day, describes the splendor of the town as buildings were built with "white stone" and the city was "adorned with several splendid palaces" (Wars, 1.21.5-6; Antiquities 15.9.6). Herod's residence was perhaps the most splendorous of all. Called the Promontory Palace by modern excavators, as it sat on a jut-out overlooking the sea, its lower level boasted an expansive inner courtyard containing an equally expansive pool.

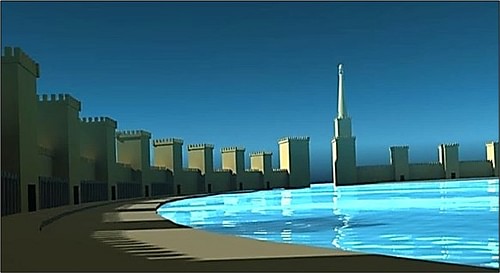

Edifices also punctuating the skyline view would have included a hippodrome for chariot races, an amphitheater for sporting events like boxing and wrestling, and a smaller theatre for the arts that is still in use today. Yet, one of the most visible structures would have been the temple. Juxtaposed between the city and Herod's harbor, with ornate Corinthian columns, the temple towered close to 30 meters (100 ft). As the temple adjoined the city's traffic grid, the Cardo Maximus was the main thoroughfare. Compared to a 12-meter (38-foot) wide modern highway, the Cardo Maximus was 16 meters (54 ft) wide. Almost 1.5 kilometers (1 mi) long, it was bordered with mosaics and was impressively lined with 700 columns, certainly of the Corinthian type. Then at the foot of the temple, as it serviced the city, was the colossal harbor.

The Harbor

As trade between the littoral nations of the Mediterranean was accomplished largely by sea, Caesarea's harbor was an essential arm servicing the city. Moreover, while the city was built on commercial trade in the Roman world, it served Rome's military concerns as well. Consequently, the artificial harbor, with no natural bay or promontory to build on, was built like a fortress at sea. Supporting a superstructure of towers and battlements; using blocks weighing up to 50 tons, its breakwaters, laid out on a circular course, housed nearly 40 acres of water. In comparison, the medium-sized port, Leptis Magna, upgraded by the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) at the end of the 2nd century CE, contained 25 acres. Herod's Harbor, therefore, certainly appears to have been built to receive mass goods. Vessels of all types and sizes plied the haven: from warships used in Roman naval warfare to huge grain ships and larger stone- and wine-carriers to the smaller merchant galleys.

The lighthouse would have been the focal point for navigators, day or night. On entering the harbor, ships would furl their sails, and in navigating the entrance, they would have relied on oars. Depending on the condition of wind and waves, a system of ropes and tugs may, at times, have aided vessels past the entrance. A harbor pilot would make sure ships were sent to their proper berths, were tugged if needed, and then properly moored to the quay. Loading and offloading from the quays would involve laborers, carts, and cranes. A harbor master, as well, would oversee all activity, including ship check-in, and then after vessels were loaded and ready to head out, he would approve check-out. He also would have been responsible for the all-important port fees and duty collection. Oversight accounting involving comparison records between trade transactions in the city and the flow of goods at the harbor would also have been critical.

Trade

The lucrative northern silk routes through Mesopotamia were controlled by Rome's ablest competitor: Parthia. Thus, Caesarea's purpose was to control the eastern trade network of ancient Rome, which included southern east-west land routes through Arabia and sea routes by way of the Red Sea, therefore monopolizing eastern Mediterranean trade in general.

Situated north of Alexandria and south of Tyre, the location of the city/harbor complex in relation to ship and trade flows indicates a purposeful plan to capture income. The substantial flow of eastern goods going west to the eastern Mediterranean coast and the general counterclockwise movement of ship traffic in the Mediterranean made the harbor a gateway to the west. Goods from India and Indonesia would have moved west, then northwest through the Arabian and Red Seas. Goods from Egypt and Africa would have moved north up the eastern Mediterranean coast for distribution there, then west throughout the Mediterranean. Likewise, as the harbor was en route for emptied or loaded vessels circuiting the Mediterranean and for loaded ships moving north up the coast from Alexandria, the harbor/town complex also interacted with Gaza, which received goods from Africa, Arabia, India, and Indonesia, the most lucrative of which would have been pepper and frankincense.

In respect to Gaza, it is important to note, that though Trajan (r. 98-107 CE) would take over Petra in 106 CE; Augustus granted Gaza to Herod 136 years earlier. Thus, not only did Caesarea own Gaza's markets and worked cooperatively with Alexandria, it would have captured trade flows from Petra with its location en route to Gaza. Incense was, in fact, carried from Petra by road to Gaza. By owning Gaza, with its diverse markets, Caesarea was placed in a position to dominate not only sea trade but also overland trade to consumer cities inland, like Bostra, Samaria, and Jerusalem.

A number of trading scenarios would also include the movement of building materials, weapons, and military personnel to these cities and other towns in the eastern end of the Mediterranean as the empire expanded. Specific ways in which Caesarea could also have generated income would include harbor and duty fees, income from the control and trade from mining operations, freighter service charges, its own buying and selling of bulk and refined goods, the reprocessing of goods coming from the east and north, and money saved by owning its own fleet of freighters. Moreover, concerning mining and the production or import of the critical alloy, bronze, Robert Bull summarizes:

In AD 6, the Romans made Caesarea the seat of provincial administration. Roman procurators, residing in Caesarea, were charged with collecting taxes, overseeing civil affairs, and recruiting personnel from the local population to serve as auxiliary legionaries. The troops were paid in bronze coins struck from a mint at Caesarea licensed by Rome. The coins were also used as a means of exchange in the area's rapidly developing economy. (27)

Provincial Capital

In 6 CE, after Herod's death, Herod's palace "became the official residence of the Roman governor, his kingdom became a Roman province with Caesarea as its main port and administrative capital" (Burrell, 56). Then when the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE was crushed by Roman soldiers garrisoned at Caesarea, Vespasian elevated the city to the status of a Roman colony. Later when the second Jewish Revolt, also known as the Bar-Kochba Revolt (132-136 CE) ended with the destruction of Jerusalem, the provincial governor of Judaea was raised to senatorial rank, and Caesarea became the capital of the Roman province of Syria-Palestina. The continued Roman presence is evident in a recent find at Herod's palace of "two column-shaped pedestals with inscriptions honoring four Roman procurators that date from the 2nd century to the early 4th century CE" (57).

As part of the early Christian sect at Caesarea, according to the New Testament, Phillip, the evangelist settled there; Peter preached there; and Paul the Apostle was held prisoner there before his trial in Rome. After this, little is known about early Christianity at Caesarea until a significant presence emerged in the early 3rd century, reflected in the establishment of a major library of 30,000 volumes by Origin (c. 185-253 CE), the theologian. Utilizing that library, Eusebius (d. 339), the church historian, wrote and oversaw Constantine I's (r. 306-337) request for 50 copies of the Bible at Caesarea's scriptorium.

Likewise, around the same time, though the Jews had been decimated at Caesarea, their own cultural resurgence occurred with the establishment of a school for the study of Judaism by Rabbi Hoshaiah, who died in 250 CE. That school produced several outstanding teachers, including Rabbi Abbahu. Jewish presence and resurgence at Caesarea is also indicated by the building of a synagogue dating to the 4th century CE. Built over the site of a house-synagogue dating to the Herodian period, this place was used until the middle of the 4th century. A new one was built over its ruins in the middle of the 5th century.

Additional evidence of the religious diversity at Caesarea came with the surprise discovery of the only Mithraeum found in Israel. The discovery first started with the excavation of a Roman building from the 3rd century CE called the Honorific Portico. The site yielded short columns bearing inscriptions honoring military notables on which presumably stood statues bearing their likenesses. However, further excavation revealed the building accessed and stood on top of a Mithraeum below. With a sole focus on Mithra, a single savior/god of light and truth portrayed in ancient Indian and Persian literature, Mithraism, as it also became popular in the Roman army, involved a male-only secret society requiring rigorous initiation rites. The Romans had converted one of Herod's underground storage vaults into a space for the practice of the cult's rites, complete with an altar, benches, and frescoes of the life of Mithra.

Later History

While the literary record falls silent about Caesarea Maritima after the 4th century, material evidence of Byzantine presence comes in the form of a Byzantine fortified wall longer than the original Herodian wall. That its encirclement protected, at least in part, the expanded suburbia of Caesaria indicates a continuation of urban activity. The Joint Expedition to Caesarea found a Byzantine structure thought to be part of a greater municipal complex. Situated along the original Cardo Maximus was a building dubbed the Archive Building. As mosaic was a particularly popular medium of Byzantine art, along with mosaic floors dating to the Byzantine period, mosaic inscriptions citing New Testament verses were found.

While the Persians of the Sasanian Empire conquered the city in 614 CE and the Byzantine emperor Heraclius retook it in 627-628 CE, reflecting Caesarea's demise as a thriving municipality and commercial enterprise, Bull believes, the Archive Building was destroyed in 639/640 CE as part of the Islamic conquest of all the Middle East and North Africa. Thus cut off from the west, with its trade network diminished and harbor dysfunctional, the final ruins of this once magnificent metropolis became a quarry, as farmers burned statues and marble for lime, and stone and marble blocks were hauled off for the building of cities elsewhere.

However, following the 7th-century devastation, while never again playing an important role in the wider network of Mediterranean trade, Caesarea experienced a seesaw of restoration and ruin. During the centuries before the Crusades, under Arab rule, the locale began a slow recovery from a farming district under the Rashidun Caliphate to a Muslim stronghold protecting a vibrant area. Nasir Khusraw, the Persian poet and traveler, describes in 1047 CE, in his Book of Travels, a place of lush gardens and fountains. William of Tyre (1130-1186) also mentions the taking of the same stronghold by the Crusaders. Though diminutive in comparison to the original Herodian and Byzantine fortifications, as the Crusaders made their own fortified enclosure adjacent to the diminished harbor, they occupied it in battle with Muslim forces from 1101 to 1187 and again from 1191 to 1265. As Bull mentions:

While the Crusader ruins contain structures that date from early in the Crusades, the prominent visible remains today - the moat, escarpment, citadel and walls containing some sixteen towers – date from 1251 when King Louis IX of France spent a full year restoring the fortifications. (33)

Finally, from the time the Mamluks retook the Crusader fortification in 1265, destroying Crusader presence, it is believed the area became uninhabited until it was sparsely repopulated by the Ottoman Empire in the mid-17th to early 19th centuries.

In modern times, in 1884, Muslim refugees fleeing the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia established a small colony on the remains of the Crusader city. Their mosque can still be seen inside the Crusader walls. While remaining a village with a mixture of mostly Muslim and some Christian inhabitants in the 20th century, timewise after the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict, the municipality of Caesarea was moved approximately 2 kilometers to the north of the old ruins.

Today, at the original site by the sea, as archaeological surveys are ongoing, the Caesarea National Park is a major tourist destination for Israel. Established in 2011, it is included on the list of Tentative World Heritage Sites. Commemorating Caesarea's storied history, with restoration works in progress and an offering of archaeological and historical exhibits, 670,000 people visited the park in 2022.