The sport known simply as the Ball Game was played by all the major Mesoamerican civilizations and the impressive stone courts became a feature of many cities. More than just a game, it could have a religious significance and featured in episodes of mythology. Contests even supplied candidates for human sacrifice and became literally a game of life or death.

Origins

The game was invented sometime in the Preclassical Period (2500-100 BCE), probably by the Olmec, and became a common Mesoamerican-wide feature of the urban landscape by the Classical Period (300-900 CE). Eventually, the game was even exported to other cultures in North America and the Caribbean.

In Mesoamerican mythology the game is an important element in the story of the Maya gods Hun Hunahpú and Vucub Hunahpú. The pair annoyed the gods of the underworld with their noisy playing and the two brothers were tricked into descending into Xibalba (the underworld) where they were challenged to a ball game. Losing the game, Hun Hunahpús had his head cut off; a foretaste of what would become common practice for players unfortunate enough to lose a game.

In another legend, a famous ball game was held at the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan between the Aztec king Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (r. 1502-1520 CE) and the king of Texcoco. The latter had predicted that Motecuhzoma's kingdom would fall and the game was set-up to establish the truth of this bold prediction. Motecuhzoma lost the game and did, of course, lose his kingdom at the hands of the invaders from the Old World. The story also supports the idea that the ball game was sometimes used for the purposes of divination.

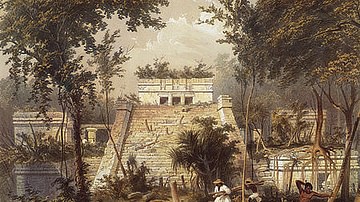

The Court

Courts were usually a part of a city's sacred precinct, a fact which suggests the ball game was more than just a game. Early Preclassic playing courts were simple, flattened-earth rectangles but by the Late Formative Period (300 BCE onwards) these evolved into more imposing areas which consisted of a flat rectangular surface set between two parallel stone walls. Each side could have a large vertical stone ring set high into the wall. The walls could be perpendicular or sloping away from the players and the ends of the court could be left open but defined using markers or, in other layouts, a wall closed off the playing space to create an I-shaped court. The court at Monte Albán, Oaxaca is a typical example of the I-shaped court. The length of the court could vary but the 60 m long court at Epiclassic El Tajín (650-900 CE) represents a typical size.

The flat court surface often has three large circular stone markers set in a line down the length of the court. Some of these markers from Maya sites have a quatrefoil cartouche indicating the underworld entrance which has led to speculation that the game may have symbolised the movement of the sun (the ball) through the underworld (the court) each night. Alternatively, the ball may have represented another heavenly body such as the moon and the court was the world.

Surviving courts abound and are spread across Mesoamerica. The Epiclassic city of Cantona has an incredible 24 courts with at least 18 being contemporary. El Tajín also has a remarkable number of courts (at least 11) and it may well have been a sacred centre for the sport, much like Olympia for athletics in ancient Greece. The earliest known court is from the Olmec city of San Lorenzo whilst the largest surviving stone playing court is at the Mayan-Toltec city of Chichén Itzá. With a length of 146 m and a width of 36 m, this court seems almost too large to be actually played in, especially with the rings set at the demanding height of 8 m.

The Rules

The exact rules of the game are not known for certain and in all probability there were variations across the various cultures and different periods. However, the main aim was to get a solid rubber (latex) ball through one of the rings. This was more difficult than it seems as players could not use their hands. One can imagine that good players became highly skilled at directing the ball using their padded elbows, knees, thighs and shoulders. Teams were composed of two or three players and were male-only. There was also an alternative version, less-widespread, where players used sticks to hit the ball.

The ball could be a lethal weapon in itself, as measuring anywhere from 10 to 30 cm in diameter and weighing from 500 g to 3.5 kg, it could easily break bones. Remarkably, seven rubber balls have been preserved in the bogs of El Manatí near the Olmec city of San Lorenzo. These balls range from 8 to 25 cm in diameter and date from between 1600 and 1200 BCE.

The Players

Players could be professionals or amateurs and there is evidence of betting on the outcome of important games. The game also had a strong association with warriors and war captives were often forced to play the game.

Players were frequently depicted in Mesoamerican art, appearing in sculpture, ceramics and architectural decoration - the latter often decorating the courts themselves - and these depictions often show that the players wore protective gear such as belts and padding for the knees, hips, elbows and wrists. The players in these works of art also typically wear a padded helmet or a huge feathered headdress, perhaps the latter being for ceremonial purposes only. Zapotec relief stones at Dainzú also depict ball players wearing grilled helmets as well as knee-guards and gauntlets.

Winners of the game received trophies, many of which have been excavated and include hachas and palmas. A hacha was a representation of the human head (early ones might have actually been heads) with a handle attached and was used as a trophy for a winning player, a piece of ceremonial equipment or as a marker in the court itself. A palma was also most likely a trophy or element of ceremonial costume worn by ball players. They are frequently represented in stone and can take the form of arms, hands, a player or a fan-tailed bird. Other trophies for game winners include stone yokes (typically u-shaped to be worn around the waist in imitation of the protective waist gear worn by players) and hand stones, often elaborately carved. All of these trophies are frequently found in graves and are reminders of the link between the sport and the underworld in Mesoamerican mythology.

As games often had a religious significance the captain of the losing team, or even sometimes the entire team, were sacrificed to the gods. Such scenes are depicted in the decorative sculpture on the courts themselves, perhaps most famously on the South ball court at El Tajín and at Chichén Itzá, where one relief panel shows two teams of seven players with one player having been decapitated. Another ominous indicator of the macabre turn that this sporting event could take is the presence of tzompantli (the skull racks where severed heads from sacrifices were displayed) rendered in stone carvings near the ball courts. The Classic Maya even invented a parallel game where captives, once defeated in the real game, were tied up and used as balls themselves and unceremoniously rolled down a flight of steps.