The idea of natural rights is the concept used in philosophy and legal studies that a person has certain rights from birth and which, because they were not awarded by a particular state or legal authority, cannot be removed, that is, they are inalienable. Such rights may include the right to life, liberty, equality, property, justice, and happiness.

Collectively, natural rights may be referred to as natural law, a subject of particular interest to philosophers of the Enlightenment. Natural rights can be contrasted with legal rights, those rights awarded to a citizen by the legal system of the state in which they are born or live (for example, the right to vote). There is much debate as to exactly which rights may be considered natural rights and, indeed, if there are any such rights independent of a given legal system. The acceptance of natural rights has often led to the formal protection of certain universal rights – what have become known as 'human rights' since they apply to everyone everywhere – in formal documents ranging from the United States Bill of Rights (1791) to the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). As S. Blackburn states:

The basic lists that have been drawn up of human rights to be respected by any legitimate constitution are surprisingly similar, suggesting a common conception of the conditions necessary for societies that accord human rights their full dignity or respect. (417)

What Are Natural Rights?

Natural rights have been a consideration of philosophers stretching from the thinkers in antiquity to modern human rights organisations. Enlightenment thinkers were primarily concerned with the question of just what system of government is best, the choices usually being rather few: democracy, limited/elitist democracy, or some form of monarchy. The debate of natural rights comes secondary to this discussion but is relevant to it since philosophers were obliged to consider the success of a particular political system by how well it protected citizen rights. Some thinkers suggested that because they believed citizens had natural rights independent of the state, then the government could be legitimately challenged, particularly if it was based on non-natural rights such as privilege. This idea was taken up by revolutionaries, for example during the French Revolution (1789-1799) and the American War of Independence (1775-1783), to legitimise their overthrow of existing governments and power regimes.

For those Enlightenment thinkers who thought there was such a thing, the following are typically considered natural rights:

- life

- liberty

- justice

- property

- the pursuit of happiness

- privacy

- freedom of speech

- self-defence

- freedom to pursue one's religion

- freedom from slavery

These were the principal concerns of Enlightenment thinkers, but, of course, a 21st-century citizen may wish to add more, such as a right to education, a right to work, or a right to choose one's gender identity. In short, then, natural rights are those rights a person may consider fundamental to their well-being and which fulfil to the maximum their role as a citizen within a particular society.

Establishing natural rights seems a rather straightforward thing to sort out amongst citizens, but even the most basic natural right, the right to life, is fraught with potential pitfalls such as 'does that right include or exclude the right to an abortion or the right to euthanasia?' In the Enlightenment, some of the greatest minds in history set themselves the formidable task of thrashing out just what should be considered natural rights.

Support for Natural Rights

The support for natural rights depends on consideration of how humans interacted before political societies were formed. This state became commonly known as the state of nature. For many thinkers of this period, the idea of natural rights was synonymous with God-given rights, the idea that God had bestowed upon humans a sense of what is required to live together harmoniously. Others, like the pre-Enlightenment thinker Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), felt that "natural law is so immutable that it cannot be changed by God himself" (Blackburn, 207).

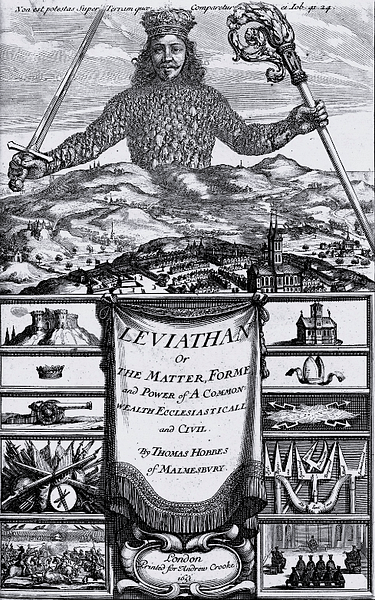

The order of nature, something increasingly revealed by the progress of the Scientific Revolution, was an argument that human society could be just as ordered, and this led some thinkers to suggest that humans did not need quite as much state interference as was the present case. Also important is one's view of human nature since this would colour how many restrictions on rights one might think necessary. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), for example, had a pessimistic view of human nature, which led him to think that a strong authoritarian government, his Leviathan, was needed to protect people's rights, most of which are given up for the common good (except the right of self-protection) in a social contract, a compromise agreement between citizens. Hobbes did not believe citizens had a right to overthrow the authority of their government, which he thought should be an absolute monarch. Hobbes' views may have been a reaction to his personal experience of the turmoil of the English Civil Wars (1642-1651).

Enlightenment thinkers were keen to show that humanity's inherent capacity for reason and their ability to compromise their self-interest for the better interests of all could permit citizens more rights than someone like Hobbes was prepared to grant. One such thinker was John Locke (1632-1704). Locke thought humans possess a natural capacity for reason and self-restraint, which means they are capable of working together for a common good. Even in a state of nature, Locke believed in the natural and universal law that "no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions" (quoted in Popkin, 77). He believed that a citizen's liberty must be protected from state interference. Locke disagreed with Hobbes' view that property was not a natural right. Indeed, the primary purpose of Locke's government is to protect property, by which he meant not only possessions which a person has invested labour in but also life and liberty, so integral is property to a citizen's existence. Locke believed that since equality is a natural right, all persons are created equal before the law. In short, individuals are more important than institutions, and the influence of the latter should be minimised by a formal separation of power between monarch, parliament, a body responsible for foreign policy, and the judiciary. Further, and unlike Hobbes, Locke believed that citizens had every right to replace a government that failed them. No government can withdraw a citizen's natural rights because they possess them independently of any such government.

Montesquieu (1689-1757), who also proposed a separation of power, believed the best way to create better citizens was to guarantee two things that he saw as self-evident positives: liberty and justice.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) suggested that humans in a state of nature are free, equal, and have two basic instincts: a sense of self-preservation and a pity for others. He suggests that such is the lack of equality and so frequent the abuse perpetrated by the wealthy and powerful, many individuals would be better off back in the state of nature. Rousseau believed that property was not a natural right but was an unfortunate creation of society. Nevertheless, the possession of natural rights means that Rousseau advocated a political society which protected these rights and reduced inequality. Citizens consent to form such a society, and so the objective of governments is the common good.

Some thinkers held other specific rights important. Denis Diderot (1713-1784), Montesquieu, Voltaire (1694-1778), and also Rousseau, all saw slavery as contrary to the natural right of freedom. Unfortunately, too many politically powerful men were making too much money from the slave trade to allow any significant reforms in that area until later centuries. Thomas Paine (1737-1809) wrote in his Rights of Man (1791 and 1792) that "every civil right grows out of a natural right, which must never be invaded by authorities, whose sole function was to strengthen them" (Yolton, 459). Paine believed that the right to freely decide one's religious beliefs was an inalienable right. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) felt that the freedom of speech was important, he once wrote, "freedom of the pen is the only safeguard of the rights of the people" (Robertson, 395).

Criticisms of Natural Rights

Many thinkers did not agree that there has ever been a state of nature or that there are any natural rights outside of a political society. David Hume (1711-1776) thought the state of nature and social contract total fictions. Neither did Edmund Burke (1729-1797) believe there had ever been such a thing as a state of nature. Rather, for Burke, any nation's institutions and the rights they protected were a product of a rich and long history, and so one particular generation has no right to make wholesale changes to these time-tested traditions.

Some thinkers believed that focussing on rights led humans and governments down the wrong path to a poor society. Kant thought the concept of dignity was more important than vague rights. Kant suggested that humans must never be used in ends in themselves; their dignity, in this sense, must not be compromised since each person has an autonomous moral worth. The utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1747-1832), who was more concerned with examining the utility of laws based on how many people they made happy, described the idea of natural rights as "nonsense on stilts" (Blackburn, 417). For Bentham and many others, rights are only brought into existence when laws create them, a view known as legal positivism. Bentham pointed out that "rights must always entail enforceable duties upon others, which could not be the case in the absence of government" (Yolton, 459)

Opponents point out that what some philosophers are really saying about natural rights is these are rights they think we should have and not necessarily what we do have. Some critics like William Godwin (1756-1836) maintain that we have no rights at all, only duties, principally the duty to contribute to the common good of all.

Other critics point out that natural rights, when listed, are all rather vague when human relations are often complex, and they require more precise definition, something usually only made possible by laws. For example, the pursuit of happiness needs a definition of what is happiness, a subject even the most reticent of philosophers could easily fill many pages on defining. In a more practical example, one might have the right to own property, say a house, but not necessarily a right to make alterations to it, if it is, for example, a property of particular architectural value (e.g. a listed historic building). Freedom of speech may be granted, but when someone calls for violent acts against others, should that right be withdrawn? There is also the problem that some natural rights might conflict with each other or with the common good. Some thinkers believe certain rights should not exist at all, for example, private property in the form of excessive wealth. Laws then need to consider a grading of rights, and it is that grading which is very difficult for all citizens to agree on. Finally, some opponents of natural rights point out that if we keep adding to the list generation after generation (for example, the right to work is a relatively recent one), then this only goes to show that natural rights are not 'natural', they are not something we are born with before societies existed, but, rather, something humans acquire and require as societies evolve and develop.

Legacy

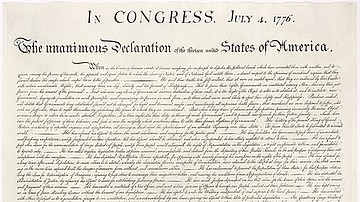

Certainly, the idea of natural rights was used by radicals as a legitimisation of their overthrow of governments. Revolutionaries in France and the United States were able to claim that because citizens had inalienable rights, a desire to change to a government that better protected these rights was also legitimate. In addition, many radicals returned to the view common in antiquity that a person can only achieve full citizenship if they have a right to participate in government (the minimum participation being the right to vote). This was not the case for all citizens in the monarchical governments of the period and certainly not the case in the colonies of those monarchies. Both the US Declaration of Independence (1776) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789) made specific mention of natural rights. The Declaration of Independence is replete with the terminology of natural rights, phrases like "We hold these truths to be self-evident", "All men are created equal", and "Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness".

The debate has continued amongst philosophers and politicians over what precise conditions certain rights should be protected. In the Enlightenment, absolutists believed the state should be able to override certain individual rights in the interests of control and security for all. Liberal thinkers believed that individuals should be protected from excessive state interference in their rights, particularly their civil rights. Civil rights came to be seen as synonymous with natural rights while other rights, non-universal ones, were considered political rights. The latter category, such as the right to vote or participate in government, received limitations. In just two examples of limits on full political participation, women were not extended the same rights as men, and those with property had advantages over those without (even for such enlightened thinkers as Rousseau, Montesquieu, and Paine).

The Enlightenment, then, made progress towards bringing clarity in regards to defining rights and what they entail and, to a limited extent, guaranteeing an equality of rights to all, but there was still much room for improvement and still many debates to come as to what exactly constitutes a right and how might those rights be best protected, prickly problems that continue to challenge governments and international bodies even today.