David Hume (1711-1776) was a Scottish philosopher, writer, historian, and important figure in the Enlightenment. Hume presented a positive view of human nature but a sceptical view of religion's usefulness. His Treatise of Human Nature was later a hugely influential philosophical work, but his fame and fortune in his own lifetime came from his popular six-volume History of England.

Early Life

David Hume was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 7 May 1711. His parents belonged to the landed gentry, his father practising law in the Scottish capital but also owning an estate at Ninewells near Berwick-upon-Tweed. As he had an elder brother, David would be obliged to find some other profession than that of estate owner. At the age of 12, he began to study law at the University of Edinburgh. Hume was not enthused by legal studies, endured some sort of nervous breakdown in 1729, and so switched his focus to literature. In 1734, he relocated to La Flèche in northwest France to study at a Jesuit college where René Descartes (1596-1650) had once studied.

Hume's career was rather unstable. He was rejected twice in his applications to lecture at university level, both by the University of Edinburgh and the University of Glasgow, largely over concerns he was an atheist. The historian H. Chisick summarises the eventful merry-go-round of posts Hume held in his career:

He became a clerk in a company dealing in sugar; a tutor; secretary on a military expedition headed by a relative; aide-de-camp to the same relative in a military embassy to Vienna; librarian to the Faculty of Advocates of Edinburgh; and secretary to the British ambassador in Paris.

(214)

A Treatise of Human Nature

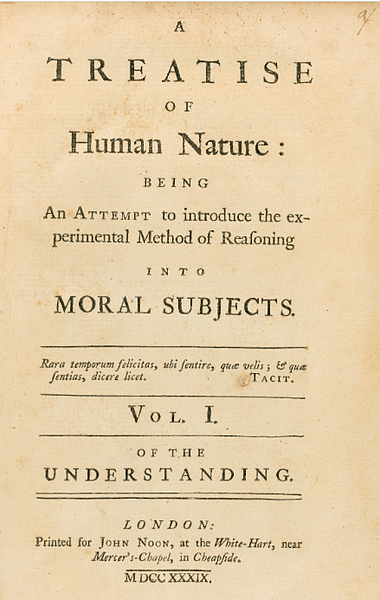

Hume's major philosophical work, written while he was in France, is A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects. The massive, three-volume work failed to stir up much of a reaction when it was published in 1740. Hume believed in his ideas, though, and so he repackaged them in shorter form: An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, published in 1748, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, published in 1751 (and which he considered his best work), and the Dissertation on the Passions, published in 1757. This trio of works, which did contain certain shifts of emphasis in Hume's thoughts, got more attention, and from 1758, they were translated into French.

Hume's treatise concerned what the author described as the 'science of man' (what we today would call the social sciences and psychology). Hume begins by investigating what exactly constitutes knowledge, and he concludes that this can only be derived from experience and observation, thus he eliminates any metaphysical sources or concepts from his work. He also eliminates any possibility of innate ideas. For Hume, we use our senses to create what he calls impressions (e.g. colour, taste, size). If we never experience these impressions ourselves then we cannot imagine them (for example, the colour red would be impossible to explain to a blind person). This rule has become known as Hume's copy principle. We can then combine this catalogue of impressions in our minds to create more sophisticated ideas or concepts, that is things which may not necessarily exist in our sensory world (e.g. we combine our impression of a horse and an animal horn to create the non-existent idea of a unicorn). Hume, then, was an empiricist, someone who believed that knowledge comes from experience.

Hume also believed that there were limits to human knowledge, such as why the force of gravity exists, what causes things to happen as they do, or why there is evil in the world. As the historian A. Gottlieb puts it, Hume intended to "encourage intellectual modesty" (203). These limits to our knowledge ensure that there remain "mysteries which mere natural and unassisted reason is very unfit to handle", said Hume (Hampson, 120). There are certain concepts we can speculate on. For example, do humans possess a soul? These speculations will always remain empty, though. We cannot prove we have a soul because we have no concept of what such a thing is (in the sense that no two people can agree exactly what a soul is). We have no concept of it because we have had no impression of it, that is, no sensory experience of a soul. Hume does not say that the idea of a soul or the self is false, only that the concept is an empty one because we cannot be precise about it. Hume goes further and suggests that when we think about the soul, that thinking process could very well be the soul (i.e. it does not exist as a thing beyond our flow of thoughts). This is known as the bundle theory, the soul is nothing more or less than a bundle of thoughts.

Above all, Hume presents a positive view of human nature, and he seeks to explain this nature so that more progress may be made in acquiring new knowledge. Hume's positive view of human nature contrasts with the belief that humans largely act out of self-interest, as presented by thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) and John Locke (1632-1704). Hume believed that humans may possess self-interest but they also naturally possess feelings of sympathy and humanity. As he poetically put it, there is "some particle of the dove, kneaded into our frame, along with the elements of the wolf and serpent" (Gottlieb, 66). These sentiments and others give humans a natural 'moral sense'. Further, Hume did not agree with Hobbes, Locke, and others in describing how people got together to form communities using some sort of social contract where the handing over of certain rights was mutually agreed to. Hume noted that such an idea is a fiction since:

Almost all the governments which exist at present, or of which there remains any record in story, have been founded originally, either on usurpation or conquest, or both, without any pretence of a fair consent or voluntary subjection of the people.

(Gottlieb, 130)

In addition, even if such a social contract had ever been voluntarily agreed to, that does not mean anyone today would be in any way bound by it. For, such a contract "being so ancient, and being obliterated by a thousand changes of government and princes, it cannot now be supposed to retain any authority today" (Gottlieb, 131). Hume seems to have favoured a constitutional monarchy as the least worst system of government.

Regarding morality, Hume believed that our passions rule our reason (and not the other way around as most thinkers suggested). Further, our moral behaviour is dictated by our passions (or emotions, if you prefer) as these are based on our experience of pleasure and pain, which we act to either enhance or reduce. Hume still believes reason is very important, indeed, he is really seeking to expand the common conception of what reason is since he wishes to add to the standard view that reason also includes emotions and experience.

History of England & Other Works

From 1752, Hume worked as a librarian in Edinburgh, the prestigious post being Keeper of the Advocates' Library. The library was the largest in Scotland and boasted some

30,000 volumes. He was eventually able to make a living from writing literary criticism and essays on non-philosophy subjects such as religion, politics, and economics. He finally established his reputation with a six-volume History of England, published one volume at a time from 1754 until 1762. The work covered the Roman period until the Stuart monarchs, but Hume presented it chronologically backwards. The book was a great success and became the standard text on this subject throughout the 18th century.

Hume hosted Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) in 1766 and even managed, in his capacity as under-secretary of state, to pull a few purse strings and secure the temperamental Swiss philosopher a state pension, but the relationship ended sourly when Rousseau accused Hume (without evidence) of being involved in a conspiracy against him. In 1769, Hume returned to Scotland and lived with his sister. Hume never married, although he had fallen in love with the Comtesse de Boufflers, who hosted intellectual salons. When pressed by his publisher to add another volume to his famous History of England, Hume reportedly declined, stating he was "too old, too fat, too lazy, and too rich" (Gottlieb, 231).

Hume On Religion

A posthumous work, deliberately not published during his lifetime – his friends had strongly advised against it – for fear of the reaction from the Church, was Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. Although there is little conclusive evidence Hume was an atheist, he was, at best (from the Church's point of view) a deist, that is, someone who believes in the existence of God but only as a creator who is not available for communication or interaction in the world he has created, meaning that organised religion is rather pointless. Hume believed that religion was based on mere superstition and fear. The possibility of miracles comes under Hume's attack, too. For Hume, there can be no knowledge of matters of faith: "The whole is a riddle, an enigma, and inexplicable mystery. Doubt, uncertainty, suspense of judgement appear the only result of our most accurate scrutiny concerning this subject" (Hampson, 121). He is essentially arguing that because we cannot agree on what exactly is 'God', then any statements about God are empty speculation. In addition to these controversial views, Hume dangerously (for the Christian Church) hints at a possible imperfection in God's creative process:

Many worlds might have been botched and bungled, ere this system was struck out; much labour lost; many fruitless trials made, and a slow but continual improvement carried on during infinite ages in the art of world-making.

(Hampson, 220)

Hume's Major Works

The most important works by David Hume include:

A Treatise of Human Nature (1740)

Essays Moral and Political (1741)

An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748)

An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751)

Dissertation on the Passions (1757)

Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779)

Death & Legacy

Hume suffered ill health in his final years, what he described as some sort of disorder of the bowels. He died in Edinburgh on 25 August 1776. Christians rather hoped the 'infidel philosopher' suffered the torment of someone about to be damned for eternity, but Hume was, according to one of his final letters, exceedingly calm at the end: "I see death approach gradually, without any anxiety or regret" (Robertson, 239). This calmness was attested by his close friend and fellow Scottish philosopher Adam Smith (1723-1790), who wrote that, on his deathbed, Hume speculated on all the ingenious excuses he might present to Charon (the ferryman of the dead in Greek mythology) in order to delay his departure from this world. Smith later described Hume in a private letter to a third party as follows:

Upon the whole, I have always considered him, both in his life-time, and since his death, as approaching as nearly to the idea of a perfectly wise and virtuous man, as perhaps the nature of human frailty will admit. (Chisick, 215)

Hume's work influenced many other philosophers, notably Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), who said that after reading Hume's work, he was roused from a "dogmatic slumber," and the utilitarian Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), who "felt as if scales had fallen from my eyes" (Gottlieb, 223) after reading Hume's treatment of morality. The unsettling ideas of Hume, which often challenge our basic preconceptions even before we start thinking about complex philosophical problems, along with his appeal to use our senses and study humanity in relation to what we see in nature, have all had increasing appeal over the last two centuries.