In the decades of the 20s and 30s of the 1st century CE, a Jew from the town of Nazareth in the Galilee began preaching that the God of Israel would soon intervene in history, restoring that nation to God's original plan and glory. From this ministry, Jesus of Nazareth ultimately came to be worshipped not only as a god but as a physical manifestation of the God of Israel on earth. There are several factors that influenced this belief: religious, historical, cultural, and political.

In the modern world, one's identity is often categorized by a specific religion (Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, etc.). What we mean by this word is a system of belief that includes concepts, rituals, and social codes. In the ancient world, the concept of religion as a separate category did not exist in the sense that we understand it today. In fact, there was no word for religion in ancient Greek or Hebrew. The modern term, which came into use in the 17th century, derives from the Latin root religio, sometimes translated as "those things that tie or bind one to the gods."

All ancient peoples believed in the total integration of the divine (the gods, the powers in the heavens and under the earth) with humans and everyday life. The ancients lived according to the customs of the ancestors (shared history, homeland, language, rituals, and mythology), which had been handed down by the gods. This provided the basis for the governing authorities, the social construction of gender roles, and appropriate codes of law and order.

Polytheism & Monotheism

Polytheism (the belief in multiple deities), or sometimes pantheism (the belief in all powers) is always juxtaposed to monotheism (the belief in one god), understood as its polar opposite. However, the terms are problematic because they are modern. No one in the ancient world would identify with being a polytheist. More importantly, there was no such concept as ancient monotheism. Like their neighbors, ancient Jews conceived of a hierarchy of powers in heaven: sons of God, the angels, archangels (the messengers from God who communicated God's will), cherubim, and seraphim. Jews also recognized the existence of lower divinities, daemons (demons), and introduced the concept of a fallen angel who eventually became Satan, the Devil.

The foundational story for the idea that Jews were monotheistic was when Moses received the ten commandments of God on Mount Sinai: "I am the Lord your God… You shall have no other gods before me." (Exodus 20:3) The Hebrew could be better understood as "no other gods beside me." This does not indicate that other gods do not exist; it is a commandment that the Jews were not to worship any other gods. We combine 'worship' with 'belief' and 'veneration', but worship in the ancient world always meant sacrifices. Jews could pray to angels and other powers in heaven, but they were only to offer sacrifices to the God of Israel. This commandment was one of the major differences between Jews and all other traditional ethnic cults. Another difference was that the God of Israel never mated with either a goddess or a human woman.

The Jewish texts consistently refer to the existence of the gods of the nations (ethnic groups):

- "Do not follow other gods" (Deuteronomy 6:14)

- "Make sure there is no man or woman, clan or tribe among you today whose heart turns away from the Lord our God to go and worship the gods of those nations" (Deuteronomy 29:18)

- "Praise O heavens, his people, worship him all you gods!" (Deuteronomy 32:43 - New Revised Standard Version)

- "Who of all the gods of these countries have been able to save their lands from me?" (Isaiah 36:20)

- "God presides in the great assembly; he renders judgment among the 'gods'" (Psalm 82:1)

In the story of the Jews' exodus from Egypt, God battled against the gods of Egypt to demonstrate who controls nature: "…I will bring judgment on all the gods of Egypt" (Exodus 12:12). This makes little sense if their existence was not recognized. While Jews only offered sacrifices to the God of Israel, they shared a common conviction that all the gods should be respected; it was perilous to anger the other gods.

Another Jewish concept was that their God often intervened in human history, either to rescue his people from oppression or to punish them when they violated his commandments. In this sense, God was selfless, manifesting himself in various forms to carry out his divine will. Earlier stories portrayed God appearing literally on earth, but later versions reduced this to the spirit of God either possessing people or being manifest in an event. When God spoke through the prophets, they went into a trance, were overcome by the spirit, and spoke the words of the deity. In this sense, they often carried the title 'sons of God', meaning a special relationship as having been called by God for a specific message or mission.

Matthew and Luke contain nativity stories of Jesus' birth where the spirit of God overcame his mother, Mary. The gospels apply 'son of God' to Jesus in both the sense of a special relationship (called by God) as well as a literal understanding as God's offspring. The gospels also incorporated another divine figure, the 'Son of Man.' This was an apocalyptic figure (best-known from the non-canonical books of Enoch) that was created by God at the same time he created the universe. This Son of Man would become the judge of the final judgment (against Israel and the nations) when God instituted his reign on earth. The gospels never depict Jesus as directly claiming the title for himself; it is always in a reference to the third person: "You shall see the son of man ..." (Mark 14:62).

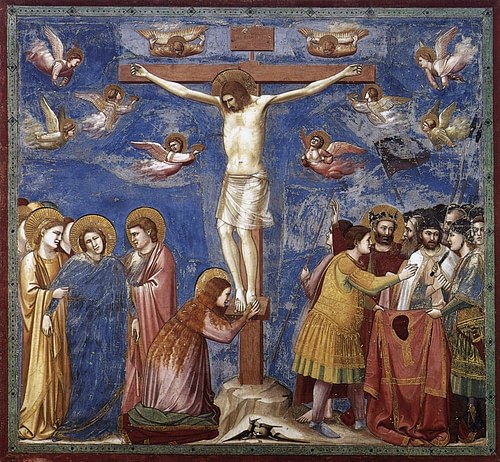

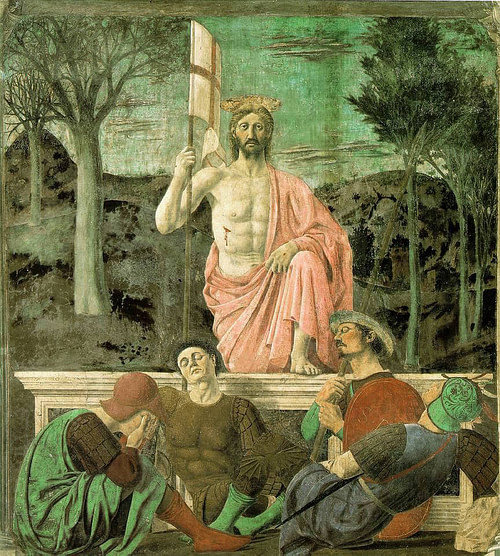

The Resurrection of Jesus

We have neither Jewish nor Roman contemporary writings from the time of Jesus. The letters of Paul date from the 50s to the 60s and are our first historical writings on Jesus of Nazareth, now deemed the 'Christ' (Hebrew: meshiach, Greek: christos). The gospels were written between 70 and 100 CE and were not eyewitness testimonies. All these writings claimed that Jesus rose from the dead on the Sunday morning (Easter) after his death by crucifixion and burial.

The idea of the resurrection of the dead was constructed from the teachings of the Pharisees who emerged as a Jewish sect c. 150 BCE. According to the books of the Prophets of Israel, God's final intervention would result in all the dead being raised and judged. The righteous would reside in a new Eden on earth while the wicked were condemned to Hell. The idea of going to heaven was a later Christian concept influenced by Greek philosophy and developed over the next few centuries.

We cannot verify the historical reality of the resurrection, but the consensus agrees that his followers experienced something (either a real person, a vision, or an experience of the 'spirit of Christ' among them). By the 1st century CE, Jewish tradition claimed that many of the patriarchs and the prophets of Israel were now in heaven as a reward for their ideal lives and teachings. In the tradition of the stories of the martyrs during the Maccabean Revolt (167 BCE), his followers utilized the concept of the vindication of the righteous; anyone who died for their beliefs was automatically exalted to heaven.

To explain how and why Christ suffered and died, early Christianity utilized the 'suffering servant passages' from Isaiah (45:52-53). These passages detailed a 'righteous servant' who suffered, died, and then was resurrected by God to share his throne. In the context of the historical Isaiah, the 'righteous servant' was the nation of Israel. Christians claimed that Isaiah rather foretold the events in the life of Christ. In the Acts of the Apostles, right before Stephen died as a martyr, he claimed to have a vision of Christ at the right hand of God.

Paul, Apostle to the Gentiles

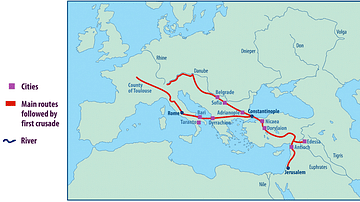

Paul was a Pharisee who experienced a vision of Jesus in heaven and became a believer. He established communities throughout the eastern part of the Roman Empire, where his mission was devoted to the now ex-pagans (Gentiles, non-Jews) who wanted to join. An earlier Christian had explained that the delay of the 'kingdom' was not problematic because Christ was coming back. It is known as the doctrine of the parousia (second appearance); when he returned, the end times would be fulfilled according to the prophets. In the interim, believers were to live proleptically, as if the kingdom were already here. This is when rules and regulations for Christian teachings began the long process of codification. Early Christians accepted the levels of powers in heaven (and hell), and Paul the Apostle often referred to the existence of the gods of other nations in his letters. He berated them for interfering with his missions. Paul claimed that when Christ returned, all the other powers in heaven would be placed under his dominion (1 Corinthians 15).

Paul related a confusing combination about Christ: Christ was both a divine pre-existent figure (present at creation and helping God with creation) and someone "... descended from David according to the flesh, born of a woman ... and declared to be son of god with power ... by resurrection from the dead" (Romans 1:3). If Paul and the early Christians had simply claimed that Jesus was now in heaven but would return to lead God's armies in the final eschatological battle, that would fit in with many Jewish views in Second Temple Judaism. However, they did this by having Jesus not only important at the end but also at the beginning –present and involved in creation – a concept that was essential to the identity of the God of Israel.

The Worship of Christ

An early hymn recited by Paul is found in Philippians 2:6-11:

[Jesus] Who, being in very nature a God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature b of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death—even death on a cross! Therefore God exalted him to the highest place and gave him the name that is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

The "name that is above every name" is the Tetragrammaton (YHWH), the name of God. "That every knee should bend" meant worship in an age-old concept of bowing down before images of various gods. Philippians. 2:6-11 is essentially an exegesis (an interpretation) of Isaiah 45:52-53. As Paul said, the suffering and death of Jesus was a stumbling block for both Jews and Gentiles. If Jesus was equivalent to God, how could he be crucified?

Paul's favorite prophet to cite was Isaiah: "For this is what the high and exalted One says—he who lives forever, whose name is holy: 'I live in a high and holy place, but also with the one who is contrite and lowly in spirit, to revive the spirit of the lowly and to revive the heart of the contrite'" (57:15). The Christian innovation here was to interpret these passages to understand that the suffering servant was a pre-existent form of God himself who selflessly humbled himself to be manifested in the earthly Jesus of Nazareth. Paul continued to honor God as God, but now added Jesus as 'Lord.' This can be quite confusing in his letters because the one word in Greek for "lord" (kyrios) can mean the God of Israel or a title for a master or magistrate.

As far as we know, the worship of Jesus consisted of hymns, prayers, petitions, baptizing in his name, healing and exorcisms in his name, and eucharistic meals in his memory. We do not know much about baptizing in Judaism, but healing and exorcisms were to be done in the name of God. Including Jesus now in the ritual formulas and identifying him with the God of Israel may have been a source of tension in the synagogue communities. For pagans who wanted to become Christians, the idea of a god manifesting himself on earth was quite common. The harder change was the cessation of all idolatry to the other gods.

Philosophical Monotheism

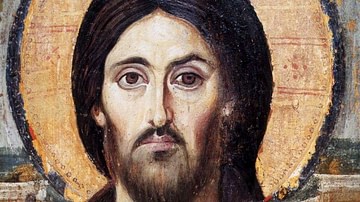

By the 2nd century CE, the separation of Christianity from Judaism was complete, Christian leaders no longer had ethnic ties to Judaism but were pagan converts from the dominant culture. As such, they had all been educated in various schools of philosophy. The schools shared a common conviction of a divine being, an original highest god, or highest good, who emanated lesser archons that ultimately created the physical universe of matter. This highest being then emanated the logos, the principal of rationality (often translated as "word"), to order all things in the universe.

The writer of the Gospel of John had accepted this concept and began with a preface that claimed that Jesus was this logos, Christ, who took on flesh (the doctrine of incarnation). The Church Fathers of the 2nd century CE enhanced the doctrine of the logos to argue against pagan philosophical criticisms of Christianity. Utilizing the same concepts, they argued that Christians not only adhered to traditional philosophy but the schools also lacked the knowledge of the true nature of the logos. During the persecution of Christians by Rome for their refusal to respect all the gods, Christians had argued that they were not a new religion, but the now replaced inheritors of the covenant of the God of Israel (the same high god of the philosophers), along with the correct understanding of the logos.

The Trinity

After Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, he was simultaneously the head of state as well as the church. A Christian presbyter in Alexandria, Arius, began teaching that if God had created everything, then at some point he must have created Christ. This placed Christ lower, subservient to God. Riots broke out in several cities. Constantine called for a meeting at Nicaea (modern-day Turkey) to resolve the issue of maintaining the concept of one God while including the worship of Christ.

At the Council of Nicaea, the debate boiled down to two choices: was Christ homo-iousios, an essence like the Father's, or was he homo-ousios, of one substance identical to the Father's? (Notice that the difference in these two words boils down to one "i," and iota). The Council opted for the second choice in that God and Christ were identical in essence, and that Christ was a manifestation of God himself on earth. This was spelled out in what became known as the Nicene Creed.

First and foremost, having Christ identical to the essence of God theoretically kept the oneness of traditional Judaism and philosophy in the forefront. With Christ identical to God, it confirmed the view (begun with early Christians) that Christ was pre-existent and helped to create the universe. This choice bolstered the importance of the now Christian Roman emperor. Over time, the claim that the kingdom of God was imminent began to fade; decades had passed, and the kingdom had not come. Christians never changed the idea, but they began to put it off to a distant future (so that they would have time to convert the world). In the meantime, we now have the concept that the Christian emperor stands in for Christ on earth until he returns. If that is the case, then the emperor has the identical power of God on earth as he rules.

This is when Christian emperors, beginning with Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE), were portrayed with a halo around their heads. When anyone approached Christian emperors, they kissed either the hem of his robe or his ring. The procession of the altar boys, the readers of scripture, and the priest of the Catholic Mass is taken from the way in which Christian emperors entered the Roman Senate.

In summary, the Christian concept of the trinity teaches that God is one, with three aspects, the Father, the Son, and the Spirit, where the Spirit is the means by which the elements of Father and Son are expressed or made manifest in the world.

A further understanding of Christ was formulated at the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE). This meeting was called to consider the natures (hypostases) of Christ: was he human or divine, and at what point in his existence was he manifest as each. The final decision was that Christ contained two simultaneous natures, both human and divine, in some mysterious fashion. At no point did one form alter or diminish the other.