Passover is a Jewish festival celebrated since at least the 5th century BCE, typically associated with the tradition of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt. According to historical evidence and modern-day practice, the festival was originally celebrated on the 14th of Nissan. Directly after Passover is the Festival of Unleavened Bread, which most traditions describe as originating when the Israelites left Egypt and they did not have sufficient time to add yeast to the bread to allow it to rise. Although the Festivals of Passover and Unleavened Bread are closely associated, this article will focus primarily on Passover.

Origins & Practice

The historical origins of Passover are unclear. Though the Hebrew Bible describes the origins of Passover, these texts were likely composed after the 6th century BCE and include evidence for editorial additions and enrichments, namely expansions of older texts. Therefore, in order to understand the origins and practices associated with Passover, we must first examine the various texts in the Hebrew Bible which describe Passover. In doing so, three characteristics will emerge concerning the nature of Passover as represented in the Hebrew Bible:

- association with Yahweh, Israel's god

- shifts in the rituals associated with Passover

- different assumptions concerning whether or not people should perform Passover.

First, Passover is always associated with Yahweh, though not necessarily Yahweh's leading the Israelites out of Egypt or passing over the doorposts of their households. In analyzing and proposing a history for the textual growth of Exodus 12:1-28, Professors Simeon Chavel and Mira Balberg suggest that the oldest layer of text in Exodus 12 does not feature "Israel's liberation through Yahweh's smiting of Egypt and does not explicitly advance it" (Chavel 2018, 299), essentially characterizing it as an ambiguous piece of folklore about a festival.

Subsequent editors, they argue, enriched this material by providing further ritual parameters and explanation of Yahweh's actions: all Israelite families must participate in consuming a one-year-old male lamb; the lamb should be flame-broiled, entirely consumed by the morning after Passover, and eaten quickly; and Yahweh will skip over or shield the Israelite households who put the lamb's blood on the doorpost from a destructive force killing their firstborn. Exodus 12:27, a response to the question concerning the purpose of celebrating Passover in future generations, best demonstrates the association between Passover and the killing of every firstborn in Egypt: “It is a Passover sacrifice for Yahweh, who passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt when smiting Egypt; but he rescued our homes.” In other words, Passover was intended to be a performance and remembrance of Yahweh's act of protecting the firstborns of Israel while in Egypt, itself a sign of Yahweh's devotion to the Israelites.

Second, the rituals concerning the actions on Passover develop throughout the Hebrew Bible. One example will suffice. In Exodus 12:9, Moses commands the Israelites to roast with fire the Passover lamb sacrifice, explicitly indicating they should not boil it with water. Yet, Deuteronomy 6:7 includes the command “you shall boil” the Passover sacrifice. Noticing the incongruity between Exodus 12:9 and Deuteronomy 16:7 in terms of proper ritual action, the author of Chronicles creatively combined the required ritual actions: “So, they boiled the Passover-lamb with fire according to the ordinance” (35:13). As subsequent generations received the Passover ritual traditions, they adjusted it in order to deal with contradictions in the traditional ritual texts.

Third, texts in the Hebrew Bible adjust the date of Passover for distinct reasons. Numbers 9:1-14, for example, offers provisions for Israelites who may have missed their opportunity to participate in Passover due to ritual uncleanliness (9:7, 10). Alternatively, Yahweh communicates through Moses that a second Passover celebration is possible. Instead of celebrating on the 14th day of the first month, they should celebrate on the 14th day of the second month. There remains an assumption, though, that all Israelites should celebrate Passover: "But the man who is pure, not on a journey, and neglects to perform the Passover, that person should be cut off from his people because he did not bring the offering of Yahweh at its appointed time" (Numbers 9:13).

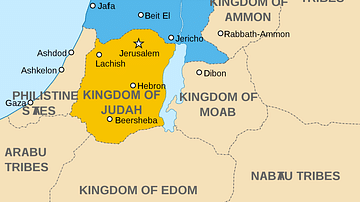

By contrast, 2 Chronicles 30 describes Hezekiah's attempt to cause all of Judah and Israel to perform Passover. The text describes that they celebrated it on the 14th of the second month due to the lack of priests available and people present (2 Chronicles 30:2-3). The purposes behind modifying the date of Passover from the first month to the second month are reflective of the cultural assumptions concerning the necessity of practicing Passover. Numbers 9 understands Passover to be an obligation incumbent on the Israelites; when 2 Chronicles 30 was composed, Passover was not perceived to be an obligation upon Israel and Judah.

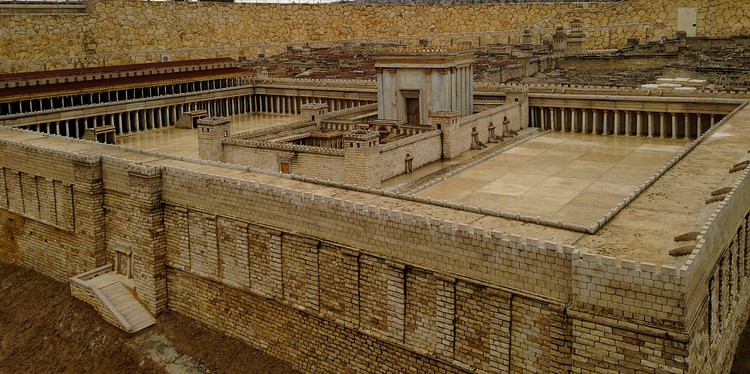

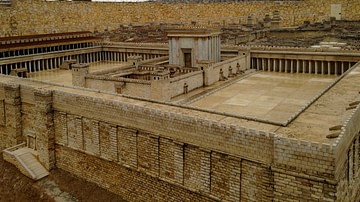

Finally, Exodus 12 presents Passover as a celebration restricted to the households of Egypt (Exodus 12:1-13). By contrast, though using similar language for the ritual parameters, Deuteronomy 16 indicates that Passover should be celebrated not at the home: “and you shall sacrifice a Passover-offering to Yahweh, either a sheep or a cattle, at the place which Yahweh will select as a dwelling for his name” (Deuteronomy 16:2), specifically clarifying in Deuteronomy 16:5 that the sacrifice should not be offered locally. While Exodus 12 and Deuteronomy 16 are both concerned with the proper practice of Passover, they reflect different historical contexts. When Exodus 12 was composed, Passover was practiced in local towns and households; by contrast, when Deuteronomy 16 was composed, Passover was more regulated, imagined to be practiced in a central temple or sanctuary.

Though Passover is often perceived as a unified, traditional ritual within Judaism, biblical passages describe divergent rituals, reflect the growth of the Passover tradition, and illuminate changes in the historical context.

Reception of Passover

Early Judaism (c. 5th century BCE - 1st century CE)

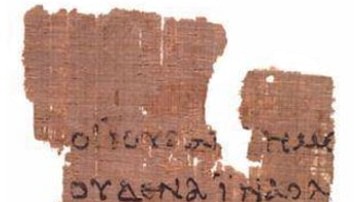

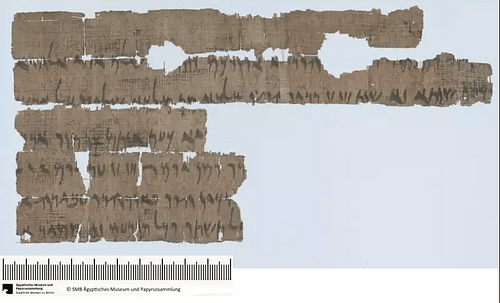

Though a wide variety of early Jewish texts discuss Passover, two will be sufficient here. In a group of texts called the Elephantine Papyri, written by members of the 5th-century BCE Jewish colony of Elephantine, Egypt, Passover is mentioned multiple times. They indicate that Jews at Elephantine practiced some form of Passover, however, they do not “provide enough information to reconstruct the history of its observance” (Silverman 1973, 386). Unlike the biblical texts, the Elephantine Papyri can be more precisely dated, and as such, they demonstrate undoubtedly that Passover was a social practice among some Jews in the 5th century BCE.

Composed in the 2nd century BCE, the Book of Jubilees is a rewritten version of Genesis and Exodus. One goal of Jubilees is to clarify the Jewish calendar for celebrating festivals. The book of Genesis narrates a story about how Yahweh tested Abraham by commanding him to kill his only son, providing a ram at the last minute. Jubilees 19:18, though, additionally describes how Abraham celebrated a festival for Yahweh after Yahweh provided a ram in lieu of having to sacrifice Isaac, his firstborn. The festival is the Festival of Unleavened Bread, which is typically associated with Passover, occurring the seven days following Passover. In doing so, Jubilees establishes that the Festival of Unleavened Bread, and implicitly the Passover, was established prior to the Israelite exodus out of Egypt.

Early Christianity (c. 1st century CE to 3rd century CE)

Passover plays a central role in the growth of Christianity as a distinct religious tradition from Judaism. By the 1st century CE, Josephus and the Gospels indicate that Passover drew large crowds of Jews to Jerusalem, the central cult site for the celebration of Passover. New Testament authors leverage Passover traditions in order to support their theological claims because, though the exact nature of Jesus is unclear from a historical perspective, he was a practicing Jew who lived in the 1st century CE.

For example, in John 19:31-36, the author portrays Jesus as a Passover lamb, whose sacrifice would ultimately cause God to redeem humanity. Likewise, Paul explicitly describes Jesus as a Passover lamb as he extends the imagery of unleavened bread metaphorically into the realm of morality (1 Corinthians 5:6-8). Similar depictions of Jesus appear in 1 Peter 1:19 and Revelation 5:6. Broadly construed, the association of Jesus' death with the Passover sacrifice “points to an understanding of the sacrifices of the Passover lamb as the remembrance of God's past act of redemption that foreshadowed the sacrifice of the Lamb of God as God's ultimate act of redemption” (Mangum 2016). Early Christians, who perceived themselves as practicing Jews, reframed the traditional narrative of Passover in order to highlight Jesus' legitimacy as a redemptive figure for all of humanity.

Rabbinic Judaism (c. 1st century CE to 7th century CE).

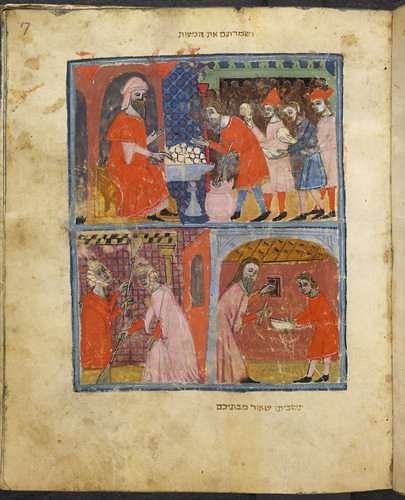

Rabbinic Judaism developed, in part, as a response to the destruction of the Jewish temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. Without the temple, Jews could no longer offer sacrifices. It is from this context which Rabbinic Judaism emerged, providing ways to worship God and perform the various ritual festivals even though the Jewish temple was no longer standing. Rabbinic Judaism sought to establish “that the Passover celebration can and should continue even without the paschal lamb,” that is the Passover lamb (Bokser 1984, 48). Although ancient Israelite and Judean religion, along with Early Judaism, perceived the temple to be central to their worship, the destruction of the Jewish temple in 70 CE forced the Rabbis to reconsider how they would perform their ancient rituals. They did so through creative readings of their holy texts and by drawing on other Rabbinic traditions.

For example, the Tosefta, a Rabbinic Jewish text of codified traditions and laws (3rd century CE), discusses the role of unleavened bread and bitter herbs, two foods mentioned in Exodus 12:8: “They shall eat the flesh that same night; they shall eat it roasted over the fire, with unleavened bread and with bitter herbs” (Exodus 12:8; 1985 JPS Translation). Because this passage indicates that three things are eaten together, namely the Passover lamb, bitter herbs, and unleavened bread, the Rabbis equated bitter herbs and unleavened bread with the Passover sacrifice (Bokser 1984, 39). They essentially figured out a way to celebrate the Passover ritual without requiring a proper sacrifice at a temple.

Ancient Near Eastern Context

Passover as a festival is reflective of its broader ancient Near Eastern context in the use of blood at the entrance of the house and with regard to the firstborn. One of the fundamental aspects of Passover is putting the blood of the Passover lamb upon the gateposts of the household, that is the front entrance:

They shall take from the blood of the Passover lamb and put it upon the two doorposts and upon the upper-cross piece of the door upon the house within which they will eat it among them. (Exodus 12:7)

Applying the blood onto the door of the household served an apotropaic function, meaning that it warded off negative influences. In the context of Exodus 12, the “negative influence” is the destructive force which kills every firstborn.

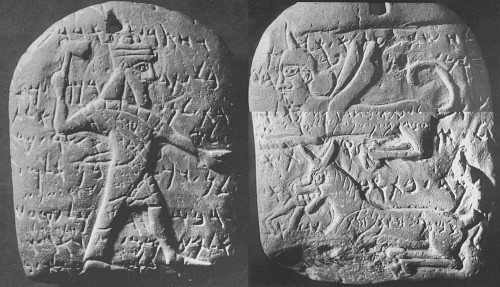

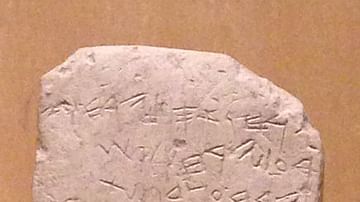

Likewise, the Arslan Tash amulet, an amulet from the 7th century BCE discovered in Syria, includes a reference to “doorposts” in one of the incantations: “And let him not come down to the door-posts.” Here, the “doorposts” are the boundary into the home, the location where the amulet was possibly placed for preventing negative influences on the household. Though the Arslan Tash amulet and the Passover blood on the doors are distinct in terms of the broader social, religious, and cultural norms, the similarities between the two texts highlight a broader cultural concern in the ancient Near East with regard to negative forces entering a household through the doorposts.

Additionally, a ritual called zukru, from a text discovered in Emar, Syria, shows remarkable similarities to Passover. First, both festivals began on the 14th day of the 1st month, lasting seven days. Second, the ritual for Passover and zukru both involve the smearing of blood on posts – the posts in Passover are to the house, the posts in zukru are at the city gates. Third, zukru is primarily a festival of “(the offering of) the (firstborn) male animals” to Dagan, a deity (Cohen 2015, 336). Likewise, Exodus 34:19 associates Passover with the offering of firstborn animals. The speaker, Yahweh, says: “All first-born of a womb are mine, as well as your male livestock, the first born of cattle and sheep.” Though these ritual actions were accomplished for different purposes, to different deities, and in distinct contexts, they demonstrate that Passover rituals are similar to broader ancient Near Eastern traditions.

Conclusion

Passover draws on a singular traditional narrative; however, texts speaking of Passover reflect different traditions, standards, rituals, and expectations depending on the historical contexts of their compositions. Such developments of Passover rituals appear to this day. In the 1980s CE, Dr. Susannah Heschel spoke at a Jewish community during Passover. One of the young girls was a lesbian. In order to express the marginalization of lesbians within Judaism, she placed leavened bread on her ritual plate. Essentially, the young girl equated the prohibition of leavened bread with the Jewish cultural convention prohibiting lesbians. Though inspired, Dr. Heschel realized that bread on the ritual plate made the plate impure, according to Jewish law. So, the next year, she placed an orange on the ritual plate, commenting: “I chose an orange because it suggests the fruitfulness for all Jews when lesbians and gay men are contributing and active members of Jewish life.” In many Jewish communities, the practice of placing an orange on the ritual plate is practiced to this day.

Thus, rituals surrounding Passover have historically developed on the basis of cultural concerns and historical context. So, Dr. Heschel did not simply add a new element to the ritual of Passover; rather, she continued the tradition of adapting, adjusting, and enriching Passover rituals. In doing so, she provided a voice and place for lesbians and gay men. One can only wonder: what other aspects of Passover will be enriched in order to provide a voice for marginalized people groups, new ideas, and cultural conventions in the 21st century CE?