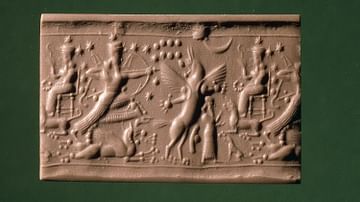

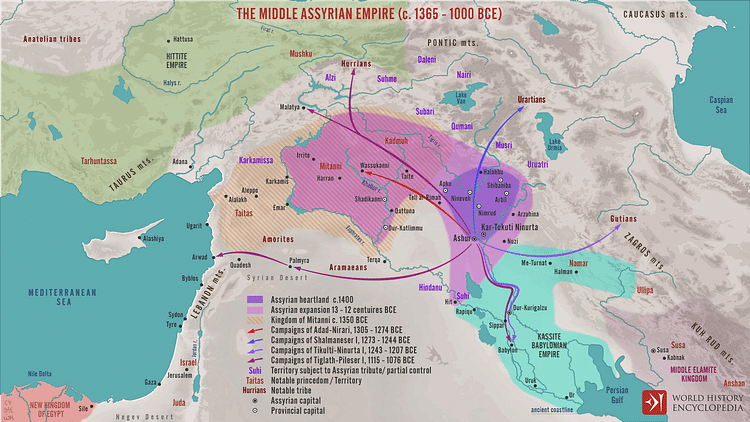

Tiglath Pileser I (reigned 1115-1076 BCE), an Assyrian king of the period known as the Middle Empire, revitalized the economy and the military that had been suffering, more or less, since the death of the king Tukulti Ninurta I (1244-1208 BCE). The old kings like Adad-Nirari I, Shalmaneser I, and Tukulti-Ninurta I had expanded the empire out from the city of Ashur and filled the royal treasuries with wealth from their conquests. The kings following Tukulti-Ninurta I, however, had been content with maintaining the empire as they inherited it, without improving or expanding on their inheritance, and so steadily lost territory to invading tribes or rebellious factions within the empire. The historian Susan Wise Bauer comments on this writing, “Tiglath Pileser wanted more. He was the first warlike king since Shalmaneser, eight generations and a hundred years earlier. He turned against the invaders and used their attacks to take more land for himself. And for a brief period – a little under forty years – Assyria regained something like its previous luminescence” (287). He campaigned widely throughout his reign with his army, initiated great building projects, and furthered the process of building a collection of books at the library of Ashur by gathering cuneiform tablets from throughout the empire.

He was a literate man who composed the first royal annals and is best known as the king who expanded the territory of the Assyrians to the extent that it truly could be called an empire. Prior to his reign, as the historian Paul Kriwaczek notes, “Assyria grew in territory, piece by piece, though with frequent reverses, to reach a first high point in the 1120's, when the king, Tiglath Pileser I, crossed the Euphrates, captured the great city of Carchemish, and reached both the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, for the first time creating an Assyrian Empire” (223). His reign was a single bright spot in the history of the empire at this time, however, and his gains would be lost by his successors who returned to the policies of containment which his predecessors had followed.

Reign & Military Campaigns

Tiglath Pileser I began his reign by repairing the temples that had been neglected and gaining support among the people by constructing new ones. In his inscriptions he writes of devoting himself first to the gods and their will. He writes,

In the beginning of my reign, Anu and Vul, the great gods, my Lords, guardians of my steps, they invited me to repair this their shrine. So I made bricks; I levelled the earth, I took its dimensions; I laid down its foundations upon a mass of strong rock. This place throughout its whole extent I paved with bricks in set order, 50 feet deep I prepared the ground, and upon this substructure I laid the lower foundations of the temple of Anu and Vul. From its foundations to its roofs I built it up, better than it was before. I also built two lofty cupolas in honor of their noble godships, and the holy place, a spacious hall, I consecrated for the convenience of their worshippers, and to accommodate their votaries, who were numerous as the stars of heaven, and in quantity poured forth like flights of arrows. I repaired, and built, and completed my work. Outside the temple I fashioned everything with the same care as inside. The mound of earth on which it was built I enlarged like the firmament of the rising stars, and I beautified the entire building. Its cupolas I raised up to heaven, and its roofs I built entirely of brick. An inviolable shrine for their noble godships I laid down near at hand. Anu and Vul, the great gods, I glorified inside, I set them up on their honored purity, and the hearts of their noble godships I delighted. Bit-Khamri, the temple of my Lord Vul, which Shansi-Vul, High-priest of Ashur, son of Ismi-Dagan, High-priest of Ashur, had founded, became ruined. I levelled its site, and from its foundation to its roofs I built it up of brick, I enlarged it beyond its former state, and I adorned it. Inside of it I sacrificed precious victims to my Lord Vul.

Although human sacrifice was not practiced by the Assyrians, the above reference (and others like it in his inscriptions) seems to indicate that Tiglath Pileser I instituted ritual human sacrifice as part of his policy of instilling terror in his enemies and awe in his subjects. Once he had taken care of the temples and commissioned other building projects, he mounted his first campaign c. 1112 BCE against the Mushku people who had claimed Assyrian territory for themselves. He then conquered the country of Comukha (Anatolia), defeating the Nairi people and then marched on the region of Eber Nari (modern Syria and the Levant) and conquered it as well. He writes,

In the beginning of my reign 20,000 of the Muskayans and their 5 kings, who for 50 years had held the countries of Alza and Perukhuz, without paying tribute and offerings to Ashur my Lord, and whom a King of Assyria had never ventured to meet in battle betook themselves to their strength, and went and seized the country of Comukha. In the service of Ashur my Lord my chariots and warriors I assembled after me . . . the country of Kasiyaia, a difficult country, I passed through. With their 20,000 fighting men and their 5 kings in the country of Comukha I engaged. I defeated them. The ranks of their warriors in fighting the battle were beaten down as if by the tempest. Their carcasses covered the valleys and the tops of the mountains. I cut off their heads. The battlements of their cities I made heaps of, like mounds of earth, their movables, their wealth, and their valuables I plundered to a countless amount. 6,000 of their common soldiers who fled before my servants and accepted my yoke, I took them, and gave them over to the men of my own territory. Then I went into the country of Comukha, which was disobedient and withheld the tribute and offerings due to Ashur my Lord: I conquered the whole country of Comukha. I plundered their movables, their wealth, and their valuables. Their cities I burnt with fire, I destroyed and ruined.

He had defeated the Aramaeans of Eber Nari (though they would continue to present a problem for him and, later, his successors) and taken Anatolia, then the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I made incursions into Assyrian territory and claimed he had conquered the land of the Amorites (the land of Eber Nari). This scenario was very similar to the one centuries before when the Babylonian king Kashtiliash had taken Assyrian border territories and called down upon himself the wrath of Tukulti Ninurta I. Tiglath Pileser I reacted in the same way and drove his army against the cities of Babylonia, capturing Babylon and destroying the central palace. He did not make the same mistake as Tukulti Ninurta I, however, and left the temples of the gods alone.

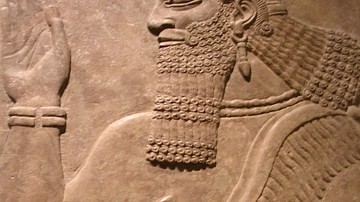

According to the historian Gwendolyn Leick, Tiglath Pileser I “was one of the most important Assyrian kings of this period, largely because of his wide-ranging military campaigns, his enthusiasm for building projects, and his interest in cuneiform tablet collections…He also issued a legal decree, the so-called Middle Assyrian Laws” (171). These laws presented the king as the administrator of the will of the gods – which was no different from earlier law codes such as the Code of Hammurabi – but the severity of their punishments was far greater. In these laws, as in every aspect of his reign, Tiglath Pileser I focused on a policy best expressed by the phrase of the later Latin poet Lucius Accius: Oderint dum Metuant – Let them hate, so long as they fear (a line made infamous by the Roman emperor Caligula). Not only were the penalties severe, however, they seemed especially so for women.

The Laws & Misogyny

The laws are inscribed on tablets discovered at the site of the ancient city of Ashur. Kriwaczek notes that:

The most immediately striking aspects of these laws are how harsh and cruel they seem compared even to Hammurabi's `eye-for-an-eye' code, and how deep is the misogyny that they express. Punishments include severe beatings, horrific mutilations and ghastly methods of capital punishment – flaying alive or impalement on a stake for instance, the original model for Roman crucifixions. This is prescribed as the punishment for a woman who procures an abortion: `If a woman has procured a miscarriage by her own act, when they have prosecuted her and convicted her, they shall impale her on stakes without burying her. If she died in having the miscarriage, they shall impale her on stakes without burying her.' For damaging a man's fertility the penalty is mutilation: `If a woman has crushed a gentleman's testicle in a brawl, they shall cut off one finger of hers. If the other testicle has become affected along with it by catching the infection, even though a physician has bound it up, or she has crushed the other testicle in a brawl, they shall tear out both her eyes.' Adultery [by a woman] is either a capital offence or punishable by disfiguration. (224).

Kriwaczek, and other scholars, have observed that it is unclear how often these punishments were meted out but, considering the social structure of the Middle Empire period, especially concerning women, they were quite likely imposed fairly regularly. Women had very little rights under the Middle Empire. They were responsible for their husbands' actions, his debts, and his crimes but could take no credit for his honors or achievements; husbands, on the other hand, bore no responsibility for the actions, debts, or crimes of their wives. Kriwaczek writes, “While no ancient society we know of could be truthfully described as a feminist paradise, Middle Assyrian regulations went far further in their oppression of women than any before” (225). This suppression of women's rights seems to correspond to the development of monotheism in Assyrian theology. As the empire grew, the central deity of the Assyrians, Ashur, could no longer only be worshipped in his temple in the city of Ashur. He had to become portable and became so by the recognition that the gods of all the conquered territories were actually only Ashur by other names. Instead of a local god who was worshipped in his temple, Ashur became the supreme god who could be worshipped anywhere because he was transcendent. As the concept of God became further removed from the natural world, the status of women declined. The reason for this has been debated for years but it could be as simple as what Kriwaczek suggests:

While males can delude themselves and each other that they are outside, above, and superior to nature, women cannot so distance themselves, for their physiology makes them clearly and obviously part of the natural world. They bring forth children from out of their wombs and produce food for their babies from their breasts. Their menstrual cycles link them to the moon. In today's society the notion that, for women, biology is destiny is rightly regarded as abhorrent. In Assyrian times, it was a self-evident fact that debarred them from full humanity (230).

The unequal status of women in Assyrian society at this time was most fully illustrated in the laws and, as noted, they were responsible not only for their own behavior but that of their husbands. Men would also be punished, however, if they witnessed a woman behaving badly, or going out in public improperly dressed, and did nothing to report her to authorities. Many of these types of laws had to do with women wearing – or not wearing – veils. Wives, widows, sacred prostitutes, concubines, and daughters of nobility had to appear in public veiled. Slave women, daughters of slaves, and common prostitutes were not to veil themselves. A woman who went out into the street wearing a veil she was not entitled to would have her ears cut off. A man who saw a woman wearing a veil she was not supposed to have – or behaving in any other way deemed unacceptable – had to report that woman to the authorities instantly or risk 50 lashes, mutilation, and enslavement for a month.

Death & Dissolution of the Empire

Tiglath Pileser I probably died in his old age of natural causes. Although there are historians who theorize that he may have been murdered, there seems scant evidence for this in the primary sources. During his reign he enlarged the empire and imported animals from different lands to the region around Ashur, possibly creating an early zoo in the city. Leick notes that, “He was also one of the first Assyrian kings to commission parks and gardens stocked with foreign and native trees and plants” (171). He was a notable hunter who claimed to have killed 920 lions and a narwhal among other animals. His law codes were held in esteem by his subjects and his royal annals emphasized his might and skill in battle. Further, he compiled a library of significant size and scope at Ashur. All of these accomplishments elevated his name in the works of later Assyrian scribes, and he was known as a truly great king. Later rulers such as Tiglath Pileser II and Tiglath Pileser III took his name in an effort to link themselves with the great monarch of the past.

Even so, Tiglath Pileser I's conquests would not outlive the king himself. Although his campaigns were far-ranging and brought in great wealth, he never established Assyrian rule firmly in the conquered territories. It was the force of his own personality that held his empire together and, with his death, it began to break apart. He was succeeded by his son, Asharid-apal-ekur, who continued his policies but made no advancements. When he died after two years, the throne was assumed by his brother Ashur-bel-kala who was challenged by a usurper and plunged the region into civil war. This turmoil allowed the regions that had not already left the empire to disengage and declare their autonomy. The Aramaeans, who had never been completely conquered, now rose against the Assyrians and took back the lands of the west. Assyria entered a period of stasis in which the rulers held on to whatever territories they could but did little else. The empire dwindled and would stagnate until the rise of the king Adad Nirari II (912-891 BCE) who again revitalized Assyria and initiated the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which would become the greatest political and military entity of the Near East for the next three centuries.