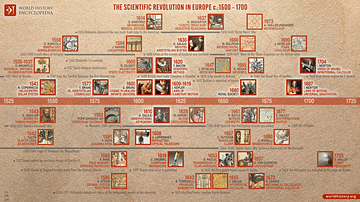

The Scientific Method was first used during the Scientific Revolution (1500-1700). The method combined theoretical knowledge such as mathematics with practical experimentation using scientific instruments, results analysis and comparisons, and finally peer reviews, all to better determine how the world around us works. In this way, hypotheses were rigorously tested, and laws could be formulated which explained observable phenomena. The goal of this scientific method was to not only increase human knowledge but to do so in a way that practically benefitted everyone and improved the human condition.

A New Approach: Bacon's Vision

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was an English philosopher, statesman, and author. He is considered one of the founders of modern scientific research and scientific method, even as "the father of modern science" because he proposed a new combined method of empirical (observable) experimentation and shared data collection so that humanity might finally discover all of nature's secrets and improve itself. Bacon championed the need for systematic and detailed empirical study, as this was the only way to increase humanity's understanding and, for him, more importantly, gain control of nature. This approach sounds quite obvious today, but at the time, the highly theoretical approach of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) still dominated thought. Verbal arguments had become more important than what could actually be seen in the world. Further, natural philosophers had become preoccupied with why things happen instead of first ascertaining what was happening in nature.

Bacon rejected the current backward-looking approach to knowledge, that is, the seemingly never-ending attempt to prove the ancients right. Instead, new thinkers and experimenters, said Bacon, should act like the new navigators who had pushed beyond the limits of the known world. Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) had shown there was land across the Atlantic Ocean. Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) had explored the globe in the other direction. Scientists, as we would call them today, had to be similarly bold. Old knowledge had to be rigorously tested to see that it was worth keeping. New knowledge had to be acquired by thoroughly testing nature without preconceived ideas. Reason had to be applied to data collected from experiments, and the same data had to be openly shared with other thinkers so that it could be tested again, comparing it to what others had discovered. Finally, this knowledge must then be used to improve the human condition; otherwise, it was no use pursuing it in the first place. This was Bacon's vision. What he proposed did indeed come about but with three notable factors added to the scientific method. These were mathematics, hypotheses, and technology.

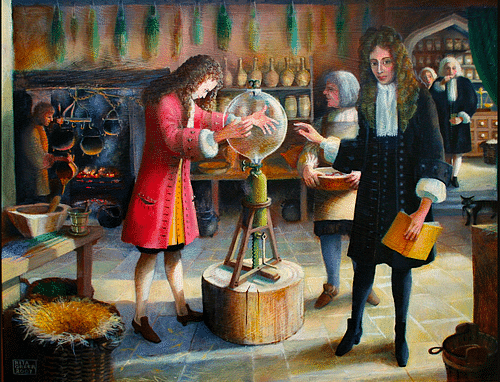

The Importance of Experiments & Instruments

Experiments had always been carried out by thinkers, from ancient figures like Archimedes (l. 287-212 BCE) to the alchemists of the Middle Ages, but their experiments were usually haphazard, and very often thinkers were trying to prove a preconceived idea. In the Scientific Revolution, experimentation became a more systematic and multi-layered activity involving many different people. This more rigorous approach to gathering observable data was also a reaction against traditional activities and methods such as magic, astrology, and alchemy, all ancient and secret worlds of knowledge-gathering that now came under attack.

At the outset of the Scientific Revolution, experiments were any sort of activity carried out to see what would happen, a sort of anything-goes approach to satisfying scientific curiosity. It is important to note, though, that the modern meaning of scientific experiment is rather different, summarised here by W. E. Burns: "the creation of an artificial situation designed to study scientific principles held to apply in all situations" (95). It is fair to say, though, that the modern approach to experimentation, with its highly specialised focus where only one specific hypothesis is being tested, would not have become possible without the pioneering experimenters of the Scientific Revolution.

The first well-documented practical experiment of our period was made by William Gilbert using magnets; he published his findings in 1600 in On the Magnet. The work was pioneering because "Central to Gilbert's enterprise was the claim that you could reproduce his experiments and confirm his results: his book was, in effect, a collection of experimental recipes" (Wootton, 331).

There remained sceptics of experimentation, those who stressed that the senses could be misled when the reason of the mind could not be. One such doubter was René Descartes (1596-1650), but if anything, he and other natural philosophers who questioned the value of the work of the practical experimenters were responsible for creating a lasting new division between philosophy and what we would today call science. The term "science" was still not widely used in the 17th century, instead, many experimenters referred to themselves as practitioners of "experimental philosophy". The first use in English of the term "experimental method" was in 1675.

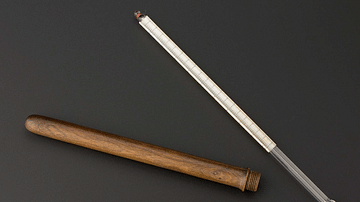

The first truly international effort in coordinated experiments involved the development of the barometer. This process began with the efforts of the Italian Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647) in 1643. Torricelli discovered that mercury could be raised within a glass tube when one end of that tube was placed in a container of mercury. The air pressure on the mercury in the container pushed the mercury in the tube up around 30 inches (76 cm) higher than the level in the container. In 1648, Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) and his brother-in-law Florin Périer conducted experiments using similar apparatus, but this time tested under different atmospheric pressures by setting up the devices at a variety of altitudes on the side of a mountain. The scientists noted that the level of the mercury in the glass tube fell the higher up the mountain readings were taken.

The Anglo-Irish chemist Robert Boyle (1627-1691) named the new instrument a barometer and conclusively demonstrated the effect of air pressure by using a barometer inside an air pump where a vacuum was established. Boyle formulated a principle which became known as 'Boyle's Law'. This law states that the pressure exerted by a certain quantity of air varies inversely in proportion to its volume (provided temperatures are constant). The story of the development of the barometer became typical throughout the Scientific Revolution: natural phenomena were observed, instruments were invented to measure and understand these observable facts, scientists collaborated (sometimes even competed), and so they extended the work of each other until, finally, a universal law could be devised which explained what was being seen. This law could then be used as a predictive device in future experiments.

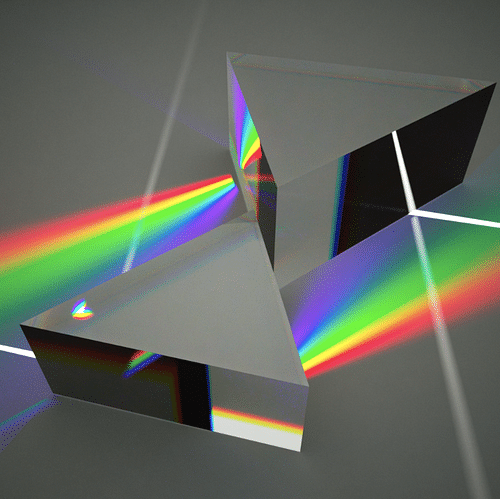

Experiments like Robert Boyle's air pump demonstrations and Isaac Newton's use of a prism to demonstrate white light is made up of different coloured light continued the trend of experimentation to prove, test, and adjust theories. Further, these endeavours highlight the importance of scientific instruments in the new method of inquiry. The scientific method was employed to invent useful and accurate instruments, which were, in turn, used in further experiments. The invention of the telescope (c. 1608), microscope (c. 1610), barometer (1643), thermometer (c. 1650), pendulum clock (1657), air pump (1659), and balance spring watch (1675) all allowed fine measurements to be made which previously had been impossible. New instruments meant that a whole new range of experiments could be carried out. Whole new specialisations of study became possible, such as meteorology, microscopic anatomy, embryology, and optics.

The scientific method came to involve the following key components:

- conducting practical experiments

- conducting experiments without prejudice of what they should prove

- using deductive reasoning (creating a generalisation from specific examples) to form a hypothesis (untested theory), which is then tested by an experiment, after which the hypothesis might be accepted, altered, or rejected based on empirical (observable) evidence

- conducting multiple experiments and doing so in different places and by different people to confirm the reliability of the results

- an open and critical review of the results of an experiment by peers

- the formulation of universal laws (inductive reasoning or logic) using, for example, mathematics

- a desire to gain practical benefits from scientific experiments and a belief in the idea of scientific progress

(Note: the above criteria are expressed in modern linguistic terms, not necessarily those terms 17th-century scientists would have used since the revolution in science also caused a revolution in the language to describe it).

Scientific Institutions

The scientific method really took hold when it became institutionalised, that is, when it was endorsed and employed by official institutions like the learned societies where thinkers tested their theories in the real world and worked collaboratively. The first such society was the Academia del Cimento in Florence, founded in 1657. Others soon followed, notably the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris in 1667. Four years earlier, London had gained its own academy with the foundation of the Royal Society. The founding fellows of this society credited Bacon with the idea, and they were keen to follow his principles of scientific method and his emphasis on sharing and communicating scientific data and results. The Berlin Academy was founded in 1700 and the St. Petersburg Academy in 1724. These academies and societies became the focal points of an international network of scientists who corresponded, read each other's works, and even visited each other as the new scientific method took hold.

Official bodies were able to fund expensive experiments and assemble or commission new equipment. They showed these experiments to the public, a practice that illustrates that what was new here was not the act of discovery but the creation of a culture of discovery. Scientists went much further than a real-time audience and ensured their results were printed for a far wider (and more critical) readership in journals and books. Here, in print, the experiments were described in great detail, and the results were presented for all to see. In this way, scientists were able to create "virtual witnesses" to their experiments. Now, anyone who cared to be could become a participant in the development of knowledge acquired through science.