The Library of Pergamon was established in the city of Pergamon (also Pergamum) by the Attalid King Eumenes II (r. 197-159 BCE) and became the most famous and well-respected center of learning after the Library at Alexandria, Egypt. The library continued in use from the reign of Eumenes II through the Byzantine Period.

The Attalid Dynasty (281-133 BCE) of Pergamon (in Asia Minor, modern-day Turkey) came from humble origins and, to establish themselves as rulers of note, patronized the arts and letters. Eumenes II, especially, held literature and learning in high regard and built the library as an annex to his Temple of Athena on the acropolis of Pergamon. At its height, the library is said to have held 200,000 books, mostly written on parchment. The demand by visiting scholars for writing material encouraged parchment production in the city and Pergamon became the leading supplier of the material during the Roman Period, so much so that the English word parchment comes from the Latin pergamenum referencing Pergamon.

Rivalry between the libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria led to both working constantly to acquire more books, leading some scholars to hide their private libraries to prevent Eumenes and his brother Attalus II (r. 159-138 BCE) or the Egyptian pharaohs Ptolemy V Epiphanes (r. 204-180 BCE) and Ptolemy VI Philometor (r. 180-164 & 163-145 BCE), and others, from confiscating them. After Attalus III (r. 138-133 BCE) willed the Kingdom of Pergamon to Rome, the Romans continued maintenance of the library.

According to the historian Plutarch (l. 45/50-120/125 CE), Mark Antony (l. 83-30 BCE) gave the library’s entire collection to his lover Cleopatra VII (l.c. 69-30 BCE) as a gift for the Alexandrian library in 43 BCE. After they were defeated by Octavian at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, Octavian, as Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE-14 CE) gave some, though not all, of the scrolls back to Pergamon.

The library was no doubt damaged along with the rest of the city in an earthquake of 262, but evidence suggests it was still in operation during the early years of the Byzantine Empire (330-1453). The final fate of the library is unknown but, most likely, the collection was removed by the librarians and other scholars before the city was finally abandoned sometime after c. 1300. Pergamon, outside of Bergama Turkey, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014, attracting visitors from around the world. A number of artifacts from the ancient city have been housed in the Pergamon Museum of Berlin since the early 20th century.

Pergamon & Philetaerus

Pergamon dates back to at least the Archaic Period in Greece (c. 800-480 BCE) although evidence suggests a much earlier habitation. The region was incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus II (also known as Cyrus the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) until it was taken by Alexander the Great in c. 334 BCE, becoming part of the Macedonian Empire. After Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, it was controlled by one of his generals, Lysimachus (l. c. 360-281 BCE) who fought against Alexander’s other successors (the Diadochi) and, while away at war, entrusted the city to one of his officers, Philetaerus (r. 282-263 BCE).

When Lysimachus was killed in battle in 281 BCE, Philetaerus kept quiet about the 9,000 talents of silver in the treasury and, instead of passing the treasure over to his new overlord, spent it on improvements to the city as well as those of the neighboring settlements. His generosity was rewarded by a tighter cohesion of the surrounding cities, enabling him to establish the Attalid Dynasty of the Kingdom of Pergamon. A eunuch since youth, Philetaerus adopted his nephew Eumenes I (r. 263-241 BCE) who then adopted his first cousin, Attalus I (r. 241-197 BCE) as heir.

Attalus I defeated the Celtic Gauls of the region, who had been harassing Pergamon for years, stabilized the region, and devoted himself to patronizing the arts. Scholar Lionel Casson comments:

Attalus I, from whom the dynasty takes its name, went in for painting and sculpture. Through lavish purchases, he put together an imposing collection – the first private art collection on record in the western world – and through commissions to the finest contemporary artists, he adorned the city with choice sculpture. (49)

After defeating the Gauls, Attalus I had been proclaimed both savior of the people and king, elevating him to nobility, and was able to forge an alliance with Rome. While beautifying his city, he also aided Rome in military campaigns against the Macedonians, guaranteeing Rome’s protection of his city and ensuring continued stability.

Eumenes II, Egypt & Parchment

Attalus I died of a stroke in 197 BCE and was succeeded by his son Eumenes II, the Attalid king who made Pergamon one of the grandest cities of Asia Minor and a cultural and intellectual center second only to Alexandria, Egypt. Alexandria was justly famous for its library, which drew the greatest minds of the time, and Eumenes II wanted the same honor for his city. Casson writes:

Eumenes II continued what Attalus had begun and, in addition, turned Pergamon into a center of literature and learning by, among other moves, giving it a library that rivaled Alexandria’s. Having started a century later than the Ptolemies, he had to go after acquisitions even more avidly than they had. The story is told that the people into whose hands Aristotle’s noted collection had come, and who lived in Pergamene territory, buried the books in a trench to hide them and keep them from falling into the royal clutches. For the location of his library, Eumenes II chose an eminently fitting place: he made it an adjunct of the sanctuary of Athena, goddess of wisdom. This came to light when excavation laid bare its remains – the earliest library remains known to date. (49)

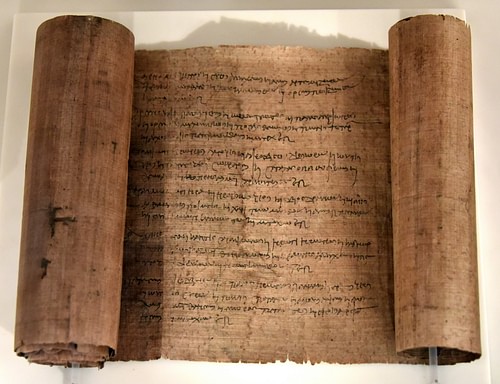

The library’s collection was provided by Eumenes II’s avid acquisition and, most likely, aided by his brother, Attalus II (r. 159-138 BCE), as well as wealthy citizens of Pergamon. At its height, according to Plutarch, the library held 200,000 scrolls although, since no catalog of holdings has survived, it is impossible to know how accurate that number is, and Plutarch was writing long after the library had reached its zenith. It is likely, however, that Plutarch’s claim is acceptable as it is recorded that the library drew some of the greatest thinkers of the era who, most likely, would not have been attracted by a modest collection and archaeological evidence also suggests adequate space for that number of books.

Among the intellectuals drawn to the city was the grammarian and Stoic philosopher Crates of Mallus (l. 2nd century BCE), who constructed the first known globe of the Earth, and was hired by either Eumenes II or Attalus II as head librarian at Pergamon. Among his other achievements, Crates is best-known as the envoy of Pergamon to Rome in c.169 or 159 BCE who, according to Suetonius in his On Grammarians (De Grammaticis), after breaking his leg by falling into an open sewer, remained at Rome to recover, giving daily lectures on grammar and was “the first to introduce the study of grammar into our city” (Suetonius, II.1). Crates was a contemporary of Aristarchus of Samothrace (l. c. 220-c.143 BCE), the head of the Library of Alexandria.

As time went on, and the rivalry between the libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria grew, the importance of acquiring and maintaining books – as well as quality staff – increased. When Aristarchus of Samothrace seemed to be inclining toward taking a position at Pergamon, he was arrested under orders from Ptolemy VIII in c. 144 BCE and died shortly after his release. This claim has been challenged, however, and, according to some scholars, it was Aristophanes of Byzantium (l. c. 257-c. 180 BCE), Aristarchus’ teacher and predecessor, who was imprisoned by Ptolemy V for preparing to move to Pergamon.

According to Pliny the Elder (l. 23-79 CE) in his Natural History, this rivalry began, almost as soon as the Pergamon library was constructed, between Eumenes II and Ptolemy V, and manifested itself, partly, in Egypt denying Pergamon the papyrus required to make copies of books:

We have not as yet taken any notice of the marsh plants, nor yet of the shrubs that grow upon the banks of rivers: before quitting Egypt, however, we must make some mention of the nature of the papyrus, seeing that all the usages of civilized life depend in such a remarkable degree upon the employment of paper – at all events, the remembrance of past events…In later times, a rivalry having sprung up between King Ptolemy and King Eumenes, in reference to their respective libraries, Ptolemy prohibited the export of papyrus; upon which, as Varro relates, parchment was invented for a similar purpose at Pergamon. After this, the use of that commodity, by which immortality is ensured to man, became universally known. (XIII.21)

This passage from Pliny has encouraged the popular misconception that parchment (made from leather - scraped and treated animal skins) was invented at Pergamon but Casson, echoing the general consensus of modern-day scholarship, writes:

Since writing on leather had long been customary in the Near East, the Pergamenes could hardly have “invented parchment.” What they might have done was to improve the manufacture of leather skins for writing and increasingly adopt their use, moves that could well have been triggered by the desire to reduce Pergamon’s dependence on imports of Egyptian papyrus paper. There is no doubt that Pergamon under the Attalids was a center for the manufacture of such skins. Rome’s supplies were so exclusively from there that the Roman word for writing-skin was pergamena “[paper] of Pergamon” (whence our term “parchment”). Even if embroidered, these stories of rivalry between the two dynasties must reflect a true state of affairs. Pliny the Elder, Rome’s polymathic encyclopedist, had no doubts: he refers matter-of-factly to “the kings of Alexandria and Pergamon who founded libraries in keen competition.” (52)

Even if Pliny was wrong about Pergamon as the origin of parchment, his observations on the Pergamon/Alexandria rivalry seem to be supported by evidence of other writers.

The Library

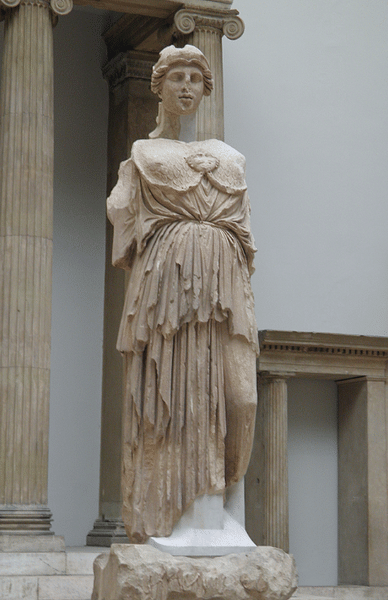

Eumenes II designed the acropolis of Pergamon to mirror that of Athens, but he seems to have purposefully located the library adjacent to the Temple of Athena to reflect the Alexandrian library which was attached to the Serapeum, the temple of the hybrid Egyptian-Greek god Serapis. The Pergamon library was a modest building by comparison but was designed for maximum efficiency, preservation of the books, and ascetic beauty. Casson describes the building as identified through modern-day excavations:

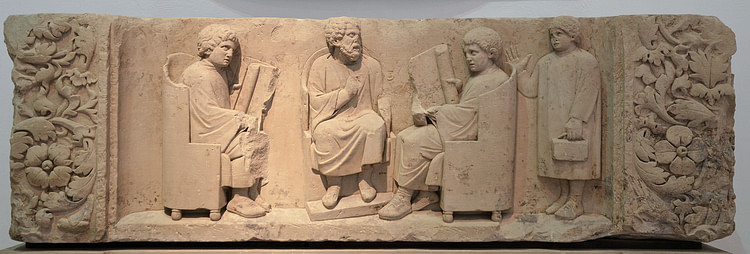

[The acropolis of Pergamon] was transformed into an imposing civic area studded with splendid buildings. Among these was a temple to Athena. It stood within a sanctuary embraced by a colonnade, and along the north side of the colonnade excavators unearthed the foundations of four rooms in a row. These, they are convinced, belonged to the library. The westernmost is the largest, roughly 13.6 m long and 15.2 m wide [44.5x50 ft], and a podium, approximately .9m [2 ft.] high and 1 m [3 ft.] wide runs parallel to its two side walls and its back wall, separated from them by a space of around .5m [1ft.]; about the middle of the back wall the podium widens to form a platform 2.74 m [8ft.] x 1.05m [3ft.]. A colossal statue of Athena was found in the temple complex and so too were some bases for busts inscribed with the names of Homer, Herodotus, and other noted literary figures. The statue of Athena, the excavators reasoned, would have stood on the platform, and the busts on the podium. A room of this size and with such décor, they further reasoned, would have served as a chamber for receptions, meetings, conferences, and so on, of the library’s learned users. The other three rooms are shorter and narrower, about 13.4m long [43ft.] and from 7 to 10m [22x32ft] in width, and these they have identified as the stacks; the walls would have been lined with wooden shelves for holding scrolls. The sole indication we have of the library’s size is provided by the anecdote about Antony’s handing over 200,00 of its books as a gift to Cleopatra; the three rooms, it has been calculated, would have had sufficient shelving space to accommodate that number. (49-50)

A 20-inch (50cm) space was left between the outer walls and the shelves to allow air to circulate, preventing the papyrus and parchment books from molding. Doorways in the stacks opened onto the colonnade, allowing patrons to take books out into the daylight for ease in reading. Copies of books may also have been made out on the colonnade or perhaps in the large westernmost room. Based on evidence from elsewhere in Asia Minor, the most popular literary works were Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (with Iliad in greater demand) and the works of Euripides (Casson, 56). This has been ascertained by the number of copies of these works extant and by references by ancient writers in their own works and in letters.

The library was primarily funded by the Attalids (until the reign of Attalus III or, possibly, till the end of it in 133 BCE) who also encouraged literacy, not only in their own city, but elsewhere. Casson writes:

The Attalids, always eager to burnish their reputation as supporters of culture, included education among their charities. Eumenes II contributed to Rhodes a huge amount of grain to convert into a fund “the interest from which was for salaries for the educators and teachers of the [citizen’s] sons.” His successor, Attalus II, in response to a request from the city of Delphi for help with education, gave a sum “to be an eternal gift for all time so that the teachers’ salaries be regularly paid” …There are a number of other places where inscriptions have been found attesting to both private and public benefactions for the support of teachers. (54)

There is no record of a fee for use of the library nor of any stipulations regarding who could use it. It is assumed, given the Attalids interest in wide-spread education, that its resources were made available free of charge to anyone who wanted to make use of them.

Conclusion

Funding for the library may have been taken over by Rome during the reign of Attalus III who had little interest in the responsibilities of a king, but this is unclear. After Attalus III left his kingdom to Rome in his will, the Romans continued funding as evidenced by the patronage of emperors such as Trajan (r. 98-117) and Hadrian (r. 117-138). The physician Galen (l. 129-216), who was born in Pergamon, almost certainly used the library for his studies before going on to pursue his education in Smyrna and Alexandria.

Although it seems clear the library was still in operation in the early years of the Byzantine Empire, details are scarce. The earthquake of 262 would have damaged it along with the rest of the city and Pergamon was sacked in c. 663 by Muslim Arabs who may have damaged or destroyed the building but there is no evidence for this either way. Pergamon was still a thriving city under the Ottoman Empire in c. 1300 but, afterward, was abandoned and at this point, if the library building was still standing, it is thought (or hoped) the books had been taken elsewhere.

The ruins of Pergamon were first excavated by the German engineer Carl Humann in 1869 but serious excavation and cataloging of the site did not begin until 1878. The Altar of Zeus (better known as the Pergamon Altar) and many other artifacts were sold by the Ottoman Empire to Germany and transported to Berlin where they were housed in the Pergamon Museum, opened in 1907. Among these artifacts is the statue of Athena that once stood in the library. The location of the library on the ancient acropolis of Pergamon may be visited in the present day outside of Bergama, Turkey where the broken columns of the colonnade still stand amidst the foundation of what was once one of the greatest libraries of the ancient world.