The House of Worship or the Ibadat Khana was established by Mughal Emperor Akbar (1542-1605 CE) for conducting religious debates and discussions among theologians and professors of different religions. Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar, famously known as Akbar the Great, was the third Mughal emperor (r. 1556-1605 CE), who extended the empire to encompass large areas of the Indian subcontinent. Contemporary chroniclers indicate that after his decisive victories and military expansion, the emperor increasingly indulged in intellectual pursuits and came in contact with ascetics and disciples of Sufi saint Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti.

Construction

Akbar seemed to have been inspired by the ruler of Bengal, Sultan Kirani, who would spend nights with 150 holy men listening to their commentaries. He also expected to receive Mirza Suleiman of Badakshan, a Sufi with a strong taste for theological discussions. Hence, he resolved to construct a debating hall that could accommodate a large number of Muslim theologians. The construction of the Ibadat Khana started in the early 1575 CE at Fatehpur Sikri (City of Victory), the then capital of the Mughal Empire. The building complex was completed in 1576 CE and the discussions were held every Thursday evening which sometimes continued through the night. Abu'l Fazl, the official Mughal chronicler writes:

A general proclamation was issued that on that night of illumination, all orders and sects of mankind-those who searched after spiritual and physical truth, and those of the common public who sought for an awakening, and the inquiries of every sect-should assemble in the precincts of the holy edifice, and bring forward their spiritual experiences, and their degrees of knowledge of the truth in various and contradictory forms in the bridal chamber of manifestation.

(Abu'l Fazl, 158.)

The discussions were discontinued within a year, however, they were resumed in 1578 CE. It is believed that from this time, theologians and intellectuals belonging to various religions and sects such as Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, and atheists were invited for the discussions at Ibadat-Khana. These discussions led the emperor to believe that there is no absolute truth and culminated in the creation of his new faith Din-i-Ilahi (Divine Religion).

Organization of the Ibadat Khana

A general idea of the structure can be constructed based on the references in Muntakhabut Tawarikh (contemporary chronicle written by Badaoni). In the center of the hall was an octagonal platform, which was the emperor's seat. The four ministers Abdur Rahim, Birbal, Faizi, and Abu'l Fazl, each had their station on different corners. The architectural plan of the Ibadat Khana has not been described in detail by any contemporary chronicler but Nizamuddin Ahmad states that it had four wings and the initial participation in the discussions was restricted to a small group of invitees. To resolve the growing disputes over seating and precedence, the emperor assigned the seats himself: on the eastern side were the amirs (high ranking nobles), Sayyids (descendants of Prophet Muhammad) occupied the western wing; ulama (doctors learned in religious law) were in the south, and Shaikhs (men of Muslim ascetic order) were in the north.

Nature of Discussions & Their Impact

Akbar was exposed to Greek philosophy by Shaikh Mubarak and his sons, Abu'l Fazl and Faizi in the early 1570s CE and was deeply influenced by Sufism (the mystical and ascetic form of Islam). It was in consequence of Akbar's growing interest in philosophy, and his inquisitiveness about religion, that the process of re-examining the aspects of Islamic theology and jurisprudence started in the Ibadat Khana. It began as a Sunni (major branch of Islam) assembly, which later became a pan-Muslim assembly and was then opened to other religions. The themes of discussions in the Ibadat Khana ranged from the nature of God in Catholicism and Islam, vegetarianism, or treatment of animals in Buddhism and Jainism, monogamy, and ancient philosophies of Hinduism to fire-worship in Zoroastrianism.

In 1579 CE, the emperor invited the first Jesuit mission to the Mughal court. The leader of the mission was an Italian, Father Rudolf Aquaviva, son of the Duke of Atri and nephew of the Society's fifth Father General. He had two companions, Father Antonio de Monserrate, a Catalan who chronicled the activities of the mission in the Mughal court, and lastly, Francisco Henriques, a Persian convert from Ormuz, in the capacity of an interpreter. The Jesuits presented the emperor with the Polyglot Bible, commissioned by Philip II of Spain. Akbar thereafter commissioned the court artists to produce the portraits of Jesus and Mary and allowed the missionaries to preach and convert in the city. The emperor spent the night discussing the Christian faith and donned Portuguese clothes and hats as a symbol of his interest in incorporating the priests into his court. The emperor's inclination towards the priests and the religious-political nature of their work attracted the critique of the chronicler Badauni and other conservative clergies of the Mughal court. Describing the impact of the presence of Jesuit priests at the court, Badaoni writes:

Learned monks also from Europe, who are called Padre, and have an infallible head, called Papa, who is able to change religious ordinances as he may deem advisable for the moment, and to whose authority kings must submit, brought the Gospel, and advanced proofs for the Trinity. His majesty firmly believed in the truth of the Christian religion, and wishing to spread the doctrines of Jesus, ordered Prince Murad to take a few lessons in Christianity under good auspices, and charged Abu'l Fazl to translate the Gospel. (Badaoni, 267)

Akbar had a keen interest in Zoroastrianism, the religion of the Parsees as well. His family's connections to Persia and his preference for Iranian rather than Mogul (Uzbeg and Chagatai) officers may have been the factors for his interest in the religious philosophy of Iran. In the latter part of 1578 CE, he invited Dastur Meherji Rana, the religious head of the Zoroastrians from Nausari, Gujarat. The Dastur taught Akbar about the rituals, ceremonies, and practices of the Parsees. Under the Parsee rules, a sacred fire was started in the palace which was not supposed to be extinguished. The Zoroastrian influence on the emperor can be seen in the practices of sun worship and fire worship. He further adopted Persian names for the calendar days and months and celebrated Persian festivals. Moreover, he gave a public appearance donning Hindu sectarian mark on the forehead.

In 1582 CE, the emperor invited Hirvijaya Suri, a Jain philosopher. He persuaded the emperor to prohibit the killing of animals on certain days. Influenced by the principles of Jainism, Akbar decreed to stop the slaughter of animals in certain periods and was personally inclined towards vegetarianism. The Suri was granted the title of 'world teacher' or 'Jagad guru'.

Some historians argue the above-mentioned measures undertaken by the emperor, including the abolition of jizya (tax on non-Muslims), could have been introduced to gain legitimacy amongst the non-Muslim subjects. Moreover, the discussions brought much discredit to the Muslim orthodoxy in the Mughal court.

Result of the Discussions

The discussions in the Ibadat Khana convinced Akbar that all religions had elements of truth, and they all led to the same Supreme Reality. This was an important phase in the development of his religious policies, which culminated in the development of the concept of sulh-i-kul (universal peace). Some historians also argue that Akbar used the debates in the Ibadat Khana to expose the bigotry and narrowness of the Muslim theologians at his court. This gave him the legitimacy to transgress the confines of orthodox Islam in his court. In a decree issued in 1579 CE, he declared himself the Imam-i Adil (the just ruler), hence transferring the ecclesiastical authority from the hands of the ulama to himself. He was thereafter proclaimed as the supreme arbiter and the highest legal authority in the empire. However, according to Badauni, he never renounced Islam. By 1582 CE, the Ibadat Khana discussions seemed to have been discontinued.

Location

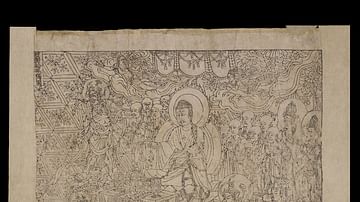

Various scholars at different points in time have identified seven to eight buildings as the Ibadat Khana. One of the buildings that have been identified is a square structure with the lotus pillar popularly known as the diwan-i-khas. The most prominent of these excavations conducted under the directorship of Professor R. C. Gaur brought to light the platforms, rooms, and walls, which resonate similarities with a structure depicted in a Mughal miniature painting of Ibadat Khana, now kept in the Chester Beatty Library. The miniature depicts Emperor Akbar seated on an elevated platform, holding a religious assembly with several scholars. Two Jesuit priests dressed in black robes identified as Rodolfo Acquaviva and Francisco Henriques can be seen participating in the religious assembly. Historian Rezavi's recent findings suggest that the structure called Daftarkhana may be identified as Ibadat Khana based on its proximity to Khwabgah (Akbar's residence), evidence from previously conducted excavations and references from contemporary historians. However, the exact location of Ibadat Khana at Fatehpur Sikri is still contentious and debatable.