Gela (Greek: Ghélas), in southern Sicily, was a Greek colony founded c. 689 BCE and it remained an important cultural centre throughout antiquity. Prospering on trade and expanding its territory, the city-state founded Agrigento. In the 5th century BCE the tyrant Gelon reigned with success but the end of that century brought attacks and destruction by Carthage. The city revived thanks to the Corinthian general Timoleon but was destroyed in 282 BCE by Phintias, ironically the tyrant of Agrigento.

Foundation

Gela is located on a long and low hill running parallel to the Mediterranean sea on the southern coast of Sicily. The first settlements in the area date back to the copper age (2800-2170 BCE) with the town of Gela being founded c. 689 BCE by Greek colonists from Rhodes and Crete, amongst whom were Antifemo of Rhodes and Entimo of Crete. The town was initially called Lindioi and then changed to Gela shortly afterwards after the nearby river.

The foundation of Gela was one of the most daring enterprises of Greek colonization in Sicily because it took possession of the island's southern coast, dangerous for the presence of the important indigenous Sicanian and Siculis centres. When the Rhodium-Cretans landed they reduced the local people to the servile state (except perhaps the women they took as wives in the first two generations), occupied the plains and the surrounding hills, and merged the indigenous culture with their own.

Early Government

It is documented that the new community followed the Greek social model but with their own independent government. From the start, power was concentrated in the hands of a few families, gathered in clans, who they awarded themselves political, judiciary and religious control. Around 600 BCE, this led to the first incident of stasis or civil war in Western history. In this case it was limited to the mutiny of the poor who had no political rights. This marginalised group, surely the majority, at some point abandoned the polis or city-state and took refuge in Maktorion, a few kilometres north of Gela. It was then that Teline, the ancestor of the tyrant Gelon, went to the rebels and persuaded them to return to Gela. Teline, as a reward for saving the city, was awarded the priesthood of Demeter and Kore who, he said, had suggested to him the best way to prevent a civil war. The two goddesses' cult spread like wildfire throughout Sicily, and Gela became the centre of the religious initiatives undertaken by Teline and his descendants (including the tyrant Gelon).

Territorial Expansion

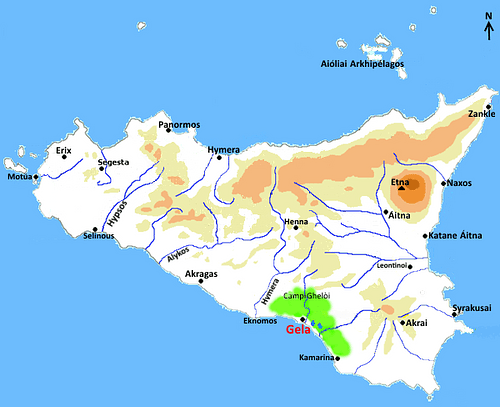

In 580 BCE, about 108 years after its birth, Gela founded Akragas (Agrigento). The Hellenization of the Akragas by the Ghelòi (the Greek name for the inhabitants of Gela), reveals a common strategy pursued by the Siceliots (the Greek settlers in Sicily) for the conquest of western Sicily; this is proved by the fact that the Megarenses, 50 years before, had founded Selinunte (628 BCE), about 100 kilometres further west of Agrigento, already the site of a Ghelòan emporium. With the founding of Agrigento, a base was created which permitted the conquest of the western Sicilian hinterland, between the southern Imera River and the Alycos (modern Platani) River. This policy brought an expansion of Gelan territory to about 80 kilometres to the north, until Sabucina, Gibil Gabib, Monte San Giuliano; to the east, as far as Kamarina, and to the west, as said above, as far as Agrigento. Just 120 years after its foundation, the area under Gelan control reached 10,000 square kilometres.

A Prospering Polis

At the beginning of the 5th century BCE, Sicily was heading towards a golden period of prosperity and its city-states would play a crucial role in the Western history. Gela, thanks in particular to its skilled craft workers, had developed a rich trade network which is well documented by archaeological excavations. In the mid-sixth century BCE, the city ceased importing from Greece and acquired a degree of autonomy and expertise so that it would become famous in its own right throughout the fifth century BCE. Particularly noteworthy were the city's temple decorations, the production of painted vases, and the making of majestic fictile (terra cotta) sarcophagi whose decoration and beauty was unparalleled in the ancient world. One splendid example of Gelan artwork is a thymiatérion or incense burner in the form of a female figurine with a bowl on her head. Although imitating other similar Aegean artifacts, in this case, the Gelan master exceeds the now frequent banality of the object, imprinting original somatic traits which make the piece unique.

The Tyrants

Gela became famous for its tyrants and the first was Cleandro. The historical information about him, unfortunately, is fragmentary. A winner a the Olympic Games of 512/508 BCE, he came to power through a coup, overthrowing an oligarchic regime whose members declared themselves descendants of the ancient colonisers. Cleandro maintained his rule over the city with mercenaries, many of whom were Siculis, and he was killed for an unknown reason by the Ghelòan Sabillo.

![Charioteer of Delphi [Illustration]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/7778.jpg?v=1619702102)

Cleandro was followed by his brother Hippocrates, who carried out a far-sighted expansionist policy and led the city of Gela to a level of wealth which made it the most powerful city in Sicily. He died in 491 BCE, during the siege of Hybla, the stronghold of the Siculis resistance. The ambitious program of Hippocrates was continued by one of his generals, Gelon, son of Deinomenes, who will go down in history as a magnanimous and fair tyrant. Married to Demarete, daughter of Theron, the tyrant of Agrigento, Gelon was also able to make himself tyrant of Syracuse after resolving there a dispute between the rich (gamòroi) and poor (kyllýrioi). In 480 BCE Gelon defeated the Carthaginians in a memorable battle fought in Imera (today's Termini Imerese), following their attempt to conquer Sicily. Pindar, the Greek poet from Thebes who spent several years in Sicily, particularly in Syracuse and Akragas, became the lyrical spokesman of that win and its glorious victor, Gelon. The tyrant was appreciated by his people who recognised him as the "second founder" of Syracuse.

When Gelon died, in 478 BCE, his place was taken by the second brother Hieron, who was in turn replaced by the third brother, Polyzelos. In 476 BCE Hieron founded Aitna (Catania) and in 472 BCE he won a great battle at Cuma against the Etruscans who had threatened the trade between Sicily and southern Italy. With the death of Hieron, which occurred in 467 BCE, power passed to the fourth brother, Thrasybulus, who was overthrown just a year later by his own family for convincing Gelon's son to give up his claim to become tyrant of Syracuse. From this moment forward, the city's history becomes unclear.

It seems that, thereafter, there were no more tyrants at Gela and some form of democratic government was adopted. Certainly, the town must have remained an important cultural centre if, in 459 BCE, the great tragedian Aeschylus, who had left with disgust his native Athens, settled there. The playwright died in the city three years later at the age of 63. The Ghelòan people raised a monument to him on which, according to tradition (Paus. I, 14; Aten. XIV, 627), these words were engraved:

Αἰσχύλον Εὐφορίωνος Ἀθηναῖον τόδε κεύθει

μνῆμα καταφθίμενον πυροφόροιο Γέλας·

ἀλκὴν δ'εὐδόκιμον Μαραθώνιον ἄλσος ἂν εἴποι

καὶ βαθυχαιτήεις Μῆδος ἐπιστάμενοςThis memorial stone covers Aeschylus Euphorion's (son),

Athenian, died in the fertile Gela: his glorious valor

the wood of Marathon could testify to it and

the long-haired Mede who knows it well.

Athens & Carthage

In 424 BCE, Gela was still a leading city, so much so that it organised a "Peace Congress" which aimed to encourage an understanding between the forever-fighting cities of Sicily so that they could unite against a common enemy, the Athenians, who threatened to invade the whole island. The results of the congress were positive, and the Greeks, seeing that trouble was brewing, thought it appropriate to withdraw and return to their country. The Athenians launched an attack nine years later but were definitively defeated by a Siceliotic army in 412 BCE.

In the spring of 406 BCE the Carthaginians launched a new attack to control Sicily. An army of 300,000 men under the command of Hannibal (not the famous one) and the young Imilcone, conquered Agrigento after eight months of fighting, devastating the city and stripping it of its treasures, including the famous "brazen bull” of Phalaris that was transferred to Carthage. Agrigento's downfall was a disaster for the Siceliotic cause because it triggered dangerous destabilising effects that culminated in many betrayals of allies, who were quick to climb on the African bandwagon. When spring of 406 BCE came, Imilcone, with an army of 120,000 men and 4,000 horsemen marched to Gela and Kamarina. The Ghelòi, confident in Syracusan assistance and in their tyrant Dionysius, prepared themselves for the battle which, unfortunately, was lost. We do not know why Dionysius decided to withdraw, permitting the destruction of Gela and causing the evacuating its population to Syracuse.

Hellenistic Revival

Gela, left uninhabited until 339 BCE, was rebuilt by Timoleon, a Corinthian general sent to Sicily to extract it out of the anarchic swamp in which it was bogged down. Under the leadership of the Greek commander, Gela received a new architectural and artistic impetus. The city rose in the western hill zone this time, utilising the ruins of the old city. Public and private buildings were reconstructed, the defensive walls were enlarged and the eastern part was used for workshops. The walls of "Caposoprano", well-known for their construction technique using squared block stones in the lower and mudbricks in the upper courses, were an enlargement of the existing defence circuit, inside which the new polis was protected. At this time a famous resident was Apollodorus, the comic poet and playwright of the "new comedy", and Archestratus, poet, philosopher and father of gastronomy, whose works reflect the well-being of the re-established Gela.

Destruction by Phintias

In 282 BCE, unfortunately, the city was definitively destroyed by Phintias, the tyrant of Agrigento, who found a new city to which he gave his own name Phintiade (today's city of Licata) and where he moved the inhabitants of Gela. This interpretation, perhaps rather too simplistic and contradictory, is reported in Diodorus Siculus' Bibliotheca historica (XXII, 2,4). The tale of Phintias' heartless attitude towards Gela seems to be simple war propaganda.

In Diodorus' account, which refers to an earlier destruction of Gela just a few years before by the Mamertines, there are obvious contradictions. One wonders why Phintias should have raged on the just collapsed city. At that moment, it could not have constituted a danger to Agrigento, if it ever had been. Akragantìnoi and Ghelòi had enjoyed a long-lasting relationship based on their common origins (let us remember that Gela had founded Akragas), but also by the continuous close family bonds between the two cities 'inhabitants. It is also unthinkable that the tyrant opened a second war front and so jeopardised the chances of victory against Syracuse. The belief that Phintias was guilty of such a hateful crime, committed against his own motherland, made him an unpopular tyrant and explained his loss of support from the other Sicilian cities (Diod., XXII, 2,6).

Later History

Gela was not definitively abandoned, rather, in Roman times it was reduced to a modest farmer's village. However Gela continued to be remembered for its great history: Virgil, in the Aeneid, mentions its "Campi Ghelòi" (the vast high wheat plain which was very famous in ancient times), and Cicero, Strabo and Pliny cite it in their works. The city was reborn 1,500 years later, for, in 1239 CE, Frederick II of Swabia rebuilt a new town on the same spot as the ancient settlement.