The French Directory, or Directorate (French: le Directoire), was the government of France from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, a period that spanned the last four years of the French Revolution (1789-1799). The Directory was unpopular, despite military successes, and faced economic crises and social unrest. It was ultimately toppled in the Coup of 18 Brumaire.

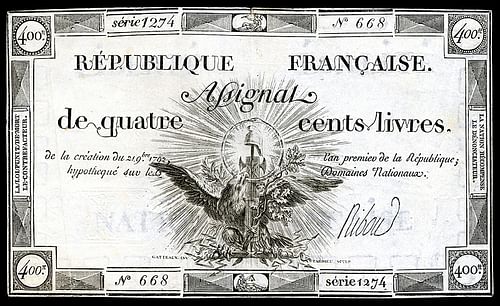

Established in response to the chaotic and bloody Reign of Terror (1793-94), the Directory sought to restore stability to France by resurrecting the initial revolutionary principles of 1789. This did little to please anyone besides the dominant bourgeois class; the leftwing Jacobins and conservative royalists both attempted to seize control of the government and engaged in a sort of political tug-of-war with the Directory in the middle. While it was fighting to survive attempted coups, the Directory also had to deal with France's economic troubles that stemmed from mountainous national debt and the depreciating value of the Revolution's paper currency, the assignat.

Meanwhile, French military victories in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) put more influence and power into the hands of generals like Lazare Hoche (1768-1797) and Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) who began interfering in national politics. Bonaparte eventually garnered enough popularity to be the face of the coup d'état that brought down the Directory and ended the Revolution itself in November 1799.

A New Constitution

On 28 July 1794, Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794) and 21 of his allies were guillotined in Paris, marking an end to the Jacobin-led Reign of Terror. The 15-month period that followed, the Thermidorian Reaction, saw a pivot away from Jacobin radicalism and back towards stable, more conservative policies that favored the bourgeois class. The Thermidorians sought a return to the revolutionary ideals of 1789 and began to dismantle radical Jacobin laws; the Jacobins themselves were being persecuted in the First White Terror, and the Jacobin Club itself was shut down for good in November 1794.

The Thermidorians promised that justice, not terror, would be the order of the day, and ended the persecution of the Catholic Church and of the aristocracy, both of which had been rampant under Jacobin rule. Yet none of their policies put food in the stomachs of starving French citizens, who were dying in droves during the bitter winter of 1794-95 due to the lack of affordable food and fuel. The Thermidorians attempted to solve the problem by issuing fresh batches of assignats, but this only served to further increase inflation. The steady stream of émigrés returning to the country caused a resurgence in royalism; citizens who favored life under a stable monarchy were no longer afraid to voice their thoughts now that the looming threat of the guillotine had largely subsided. Royalists began a well-funded propaganda campaign that disparaged the Republic and looked back at the old monarchy with rose-tinted glasses.

Although the Thermidorians had claimed to have saved France by overthrowing Robespierre, the Republic was clearly unwell. France's economic situation was scarcely better than it had been before the Revolution, and in 1795, social unrest manifested itself in the form of popular insurrections, first from the Jacobin left (Prairial Uprising) and then from the royalist right (revolt of 13 Vendémiaire). Such were symptoms of a dangerous disease, one that threatened to kill the Republic from within. The remedy, to the minds of the Thermidorians and others in France, was to adopt a new constitution.

The nation had effectively been without one since the king was overthrown in August 1792; of course, the Jacobins had written a constitution of their own, but it was deemed impractical and unrealistic by the Thermidorians. One deputy, Boissy d'Anglas, described the Jacobin constitution of 1793 as having been "drafted by schemers, dictated by tyranny, and accepted through terror" (Doyle, 319). The Thermidorians set up an 11-man committee to write a constitution more suitable to their agenda, which was finished in August 1795 and stipulated the creation of a new government. Such a government, known to history as the French Directory, was inaugurated on 2 November 1795 and governed France for four turbulent years.

The Directory

The Constitution of Year III (1795), as this new constitution was known, was faintly reminiscent of its two immediate predecessors; it included the seminal Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen as its preamble, albeit in an amended form. Yet, the Thermidorian constitution was less democratic than its Jacobin cousin, limiting the voting pool to male taxpayers over the age of 21; if residing in a town with a population greater than 6,000, eligible voters also had to own or rent land worth between 100 and 200 days' labor. This decreased the number of qualified voters from roughly 6 million to approximately 1 million. To foster stability, the new constitution was intentionally difficult to amend, a process supposed to take no less than nine years to complete. The constitution also replaced the 48 districts of Paris, notorious as breeding grounds for insurrection, with 12 arrondissements.

The government itself had a double-chambered legislature, the Corps Législatif, which consisted of an upper house, the Council of Ancients, and a lower house, the Council of 500. The Council of 500 was comprised of deputies 30 years of age or older who were responsible for proposing legislation; the Council of Ancients, comprised of 250 deputies over the age of 40, held the power of accepting or vetoing the legislation. Executive power rested in the hands of five Directors, men who were at least 40 years old and who had previously served in a ministerial or legislative office. Directors were chosen by the Council of Ancients, from a list provided to them by the Council of 500; every year, the Directors drew lots to determine which one would retire, and a new man would be chosen to replace him. The Directory was arranged this way to ensure a separation of powers.

Economic Troubles

One of the most pressing issues facing the new Directory was the matter of inflation. By December 1795, the value of the assignat currency had fallen to 1 percent of its face value; in Paris, bread was costing 50 livres, butter 100, and soap 170. Prices had also been driven up by a British blockade and a poor harvest season, forcing the government to strictly ration all foodstuffs, candles, and firewood. By this point, it was clear that the assignat was beyond saving, and it was finally discontinued in February 1796. A ceremony was held on the Place Vendôme to destroy the printing presses that had been used to print assignats.

In their place, the Directory introduced a new currency called the mandats territoriaux. The mandats were paper banknotes backed by the value of national lands that had been confiscated from the aristocracy or the church. This currency failed even quicker than the assignats; in February 1797, only a year after they were first issued, the mandats had become worthless and were demonetized. The failure of the mandat led to a return of metal currency and, begrudgingly, to the rise of a central bank by 1800.

Along with inflation, the Directory faced enormous national debt, the same issue which had started the Revolution. The Directory claimed bankruptcy on two-thirds of the debt, but promised to pay the last third; this managed to stabilize the situation. While the Directory sought to fill its coffers with new taxes on luxury goods, the treasury was largely sustained thanks to victorious French armies. Every time a city was captured, it was forced to send a large sum of money to Paris. French generals also raided conquered territories for their priceless works of art, which were used to fill the Louvre, only recently converted into a museum. Napoleon's Italian Campaign of 1796-97 was especially lucrative.

Social Unrest: 1796-1797

France's food scarcity and economic issues did nothing to ease the general suffering felt throughout the nation. As the winter of 1795-96 proved just as bad as the year before, citizens began to look back with nostalgia to earlier, better days; for Jacobins and impoverished sans-culottes, this referred to the days of the Terror, when bread had been affordable and the Constitution of 1793 had been a beacon of hope. In 1796, one woman lamented:

It's a fine bugger of a republic for robbers. First, they guillotine us, now they make us die of hunger. What's more, Robespierre didn't let us waste away, he only brought death to the rich; this lot are letting people die every day! (Doyle, 326)

Of course, times had not been that great under Robespierre, and more than just the rich had been killed during the Terror. But this sentiment reflected a longing for a time when the revolution had been a people's movement, not merely a bourgeois affair. In late 1795, like-minded radicals gathered at the Pantheon Club, which had replaced the Jacobin Club as the rallying place for Jacobins. There, they listened to staged readings of an extremist newspaper entitled Le Tribun du Peuple, written by an agitator called Gracchus Babeuf. Babeuf, going further than any Jacobin had before, called for the abolition of private property in favor of communal ownership, an idea that would later be associated with communism. This mini Jacobin renaissance disturbed the Directory, which ordered General Napoleon Bonaparte to close the Pantheon Club on 27 February 1796.

The closure did nothing to quell leftwing fervor. In the spring of 1796, Babeuf and his colleagues began to plot a coup to overthrow the Directory. Gracchus Babeuf and the Conspiracy of Equals never got very far; it was betrayed to the Directory, who ordered the arrests of Babeuf and his co-conspirators on 10 May, before it could even get off the ground. Babeuf and one other conspirator were guillotined on 27 May 1797 and seven others were deported, but the foiling of the plot did little to ease social unrest, which then took form among the political right.

Like the Jacobins, the royalists also looked fondly back to better days; but rather than wishing for a new Robespierre, the royalists longed for a new king. They were divided, of course, over what a restored monarchy might look like: some were constitutional monarchists, while others favored monarchical absolutism, some supported the claim of Louis XVIII of France, while others supported the junior Orleanist branch headed by future king Louis-Philippe. But the royalists put aside their differences and plotted to gain power. Unlike Babeuf, the royalists planned to obtain power through legal means, and set their sights on the Directory's first elections, in the spring of 1797.

From their headquarters in the rightwing Clichy Club, the royalists embarked on a vast propaganda campaign, emphasizing the poor quality of life in an unstable republic, and pointing to the corruption of the Directory. The Directory, unnerved by growing royalist support, attempted to fight back by revoking the right to vote from aristocrats who had not yet been removed from the émigré list. But it was too late, and the elections of 1797 proved the unpopularity of the Directory. Out of the 234 deputies who had been in power since the days of the Thermidorians, only 11 were re-elected. The royalists, by contrast, gained 182 seats in the legislature, and General Jean-Charles Pichegru, a Jacobin-turned-monarchist, became president of the Council of 500.

Coup of Fructidor

The rise of the royalists signaled trouble for the republic. Great Britain and Austria, the last of Europe's great powers to still be at war with France, immediately moved to start peace negotiations, in the hopes that they would get better terms from a divided France; likewise, the royalists hoped that conditions of peace could include a restoration of monarchy. This was resisted by the generals, including Lazare Hoche and Napoleon Bonaparte. Bonaparte sent secret letters to the Directors, providing evidence that Pichegru had met with agents of Louis XVIII and had plotted to restore the monarchy in a military coup.

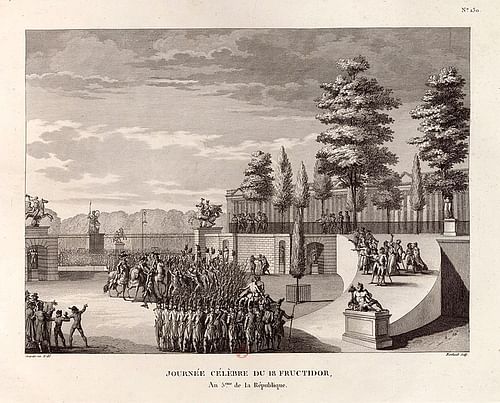

Three of the Directors, Paul Barras, Jean-François Rewbell, and Louis-Marie de La Révellière, hatched a plot to retake control of the government through a coup of their own. During the summer of 1797, soldiers commanded by General Hoche arrived in Paris, ostensibly on their way to Brest to prepare an invasion of Britain. They seemed in no hurry to leave the capital and were soon joined by soldiers under General Pierre Augereau, fresh from Bonaparte's army in Italy. At dawn on 4 September 1797 (18 Fructidor Year V in the French Republican Calendar), the conspirators pounced; the soldiers seized the city's strongholds and surrounded the legislative chambers. They shut down royalist newspapers, arrested royalist journalists, and covered the city with papers that disclosed Pichegru's treasons.

53 deputies were arrested, including Pichegru, who was deported; the two Directors who had not taken part in the coup, Lazare Carnot and François-Marie de Barthélemy, were ousted. With the support of the troops, the council annulled the recent elections, leaving 177 seats vacant. The Coup of 18 Fructidor, as it became known, was bloodless, but set a dangerous precedent for the military seizing power. The days that followed saw the implementation of anti-royalist legislation; émigrés who had returned to France with monarchist intentions were given 2 weeks to leave, on pain of death. 160 aristocrats were executed under this law. Likewise, the clergy were compelled to swear oaths denouncing royalism or else be deported. Churches were confiscated by the government and rededicated as Theophilanthropic temples, a new deistic sect.

These anti-aristocratic, anti-Catholic policies fostered a Jacobin resurgence; the elections of 1798, held between 9-18 April, saw a strong Jacobin turnout. The royalists had been barred from elections after Fructidor, and the moderates were still in disarray after losing the elections of 1797, leaving the Jacobins to claim a majority in the Corps Législatif.

Military Successes

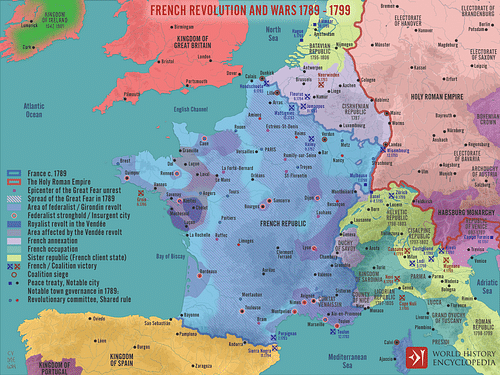

The era of the Directory was defined largely by French military victories, as the groundworks for the Napoleonic Wars were inadvertently being lain. In 1795, Prussia and Spain dropped out of the War of the First Coalition, and the Dutch Republic was turned into the Batavian Republic, a French client state and the first of many 'sister republics'. Lazare Hoche, the dashing young Republican general, put an end to the protracted War in the Vendée in 1796 and led the failed French Expedition to Ireland the same year. Hoche's hopes of another attempt at invading the British Isles were thwarted when he suddenly died on 19 September 1797 of tuberculosis.

Elsewhere, French armies appeared invincible, especially in Italy where Bonaparte stunned Europe with his boldness and military brilliance. In October 1797, after the Fructidor Coup dashed the Coalition's hopes of treating with sympathetic royalists, Austria signed the Treaty of Campo Formio, signaling the end of the War of the First Coalition; Great Britain was now the only major European state to remain at war with France. During the Congress of Rastadt in 1798, overconfident French diplomats bullied the German states into ceding the left bank of the Rhine. The French, who had also annexed Belgium, were intent on expansion.

This show of French aggression unnerved the European powers, who were further disturbed by France's subsequent actions. In January 1798, a French-backed coup overthrew the Swiss Confederation, which was replaced with a French sister republic, the Helvetic Republic, giving France free access to the Alpine passes. On 28 December 1797, a riot in Rome led to the death of a French general; Bonaparte used this pretext to invade the Papal States. On 15 February, he established another sister republic in Rome and dragged Pope Pius VI to Valence as a prisoner; the pope, who had once condemned the French Revolution, died a year later on French soil.

Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign, beginning in July 1798, was the final straw. The campaign was born from a plot hatched by Bonaparte and French foreign minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand to seize Egypt from the Ottomans. This blatant act of aggression was intolerable to the European powers, who began to form another alliance against France in 1798. This resulted in the War of the Second Coalition (1798-1802), which plunged Europe into total war once again, after barely a year's respite from the fighting.

End of the Directory

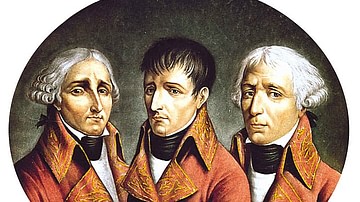

General Bonaparte returned from Egypt in October 1799 as a popular man. By this point, the 1799 elections had confirmed neo-Jacobin control of the legislature; Napoleon's own brother, Lucien, was a staunch Jacobin who was elected president of the Council of 500, although he was only 24. That same year, Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès became a Director; Sieyès, who disapproved of the Constitution of Year III, saw this as an opportunity to stage a coup of his own and create a new government. He garnered the support of influential figures like Talleyrand but knew he needed a popular general to be the face of the coup. After his first choice, General Joubert, was killed in battle, Sieyès settled on the immensely popular Napoleon Bonaparte.

The subsequent Coup of 18 Brumaire (9 November) was a success; with the help of Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon and his soldiers compelled the end of the Directory. In its place, a French Consulate was formed consisting of Sieyès, Roger Ducos, and Napoleon as the three consuls. Yet Napoleon had no intention of being the most junior partner in the trio; he outmaneuvered his fellow consuls and was the driving force behind the new Constitution of Year VIII. Before long, Napoleon was First Consul and well on his way to becoming emperor of the French. The Directory was over, and the French Revolution was finally at an end.