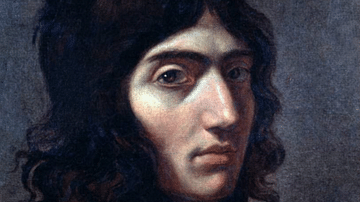

The Cult of the Supreme Being was a deistic cult established by Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794) during the French Revolution (1789-1799). Its purpose was to replace Roman Catholicism as the state religion of France and to undermine the atheistic Cult of Reason which had recently gained popularity. It represented the peak of Robespierre's power and went unsupported after his downfall.

In establishing the Cult of the Supreme Being, Robespierre intended to shepherd the French Republic toward a state of absolute virtue, or moral excellence. He meant to use the idea of an abstract godhead, or Supreme Being, to educate the French people on the relationship between virtue and republican government, thereby creating a perfectly just society. According to the decree of 18 Floréal (7 May), the cult acknowledged the existence of a Supreme Being as well as the immortality of the human soul. Worship of the Supreme Being was to be done through acts of civic duty.

On 8 June 1794, a Festival of the Supreme Being was held on the Champ de Mars. Robespierre, who was then at the apex of his dictatorial powers, took on a central role in the festivities, giving him the appearance of pontiff to the new religion. It is thought that distaste for the cult, and for Robespierre's central position in it, helped lead to his downfall a little over a month later. According to historian Mona Ozouf, the Festival represented a certain revolutionary stiffness that foreshadowed the "sclerosis of the Revolution" (Ozouf, 24).

The Church & the Revolution

The French Revolution had been at odds with the Catholic Church since its beginning. A fundamental pillar of the oppressive Ancien Régime, the institution of the Church seemed to stand for corruption, superstition, and backwardness, all contrary to revolutionary values. In November 1789, Church lands were seized and nationalized to bolster France's withering economy, while the Civil Constitution of the Clergy forced all practicing clergymen to swear oaths to the new constitution and pledge that their loyalty to the French state would supersede their loyalty to the Pope in Rome.

Yet in this early phase of the Revolution, it was the institution of the church that was under attack rather than Christianity itself. Many citizens would still consider themselves Catholic, and many even sought to reconcile the Gallican Church with the Revolution; most early revolutionary festivals included sermons from constitutional priests, who made sure to draw parallels between revolutionary values and the Gospels and to refer to Jesus Christ as the ideal sans-culotte. Infants would be baptized with a tri-color cockade pinned to their diapers, being simultaneously given over to both Christ and the fatherland.

But before long, the differences between the Church and the Revolution became too vast to ignore. The Pope condemned the Revolution and excommunicated certain clergymen who had supported the new constitution. King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792), after his failed flight to Varennes, made clear his disgust at the Revolution's treatment of the Church, further helping to associate it with corrupt aristocracy. In late 1791, the French Legislative Assembly declared that all clergymen who had not yet sworn oaths to the constitution were guilty of conspiracy and sentenced to deportation. The Assembly also legalized divorce and declared that all records of births, deaths, and marriages would henceforth be handled by secular officials only, removing an important function from the Church.

Rise of Atheism: The Cult of Reason

Of course, the most fervent attempts at de-Christianization would not come until around the time of the Reign of Terror in September 1793. An anti-clerical, atheistic movement known as the Cult of Reason had arisen around Paris, propped up by an extremist, 'ultra-revolutionary' faction known as the Hébertists. The Cult of Reason rejected the existence of God in any form, instead dedicating itself to the celebration of Enlightenment values such as liberty and rationalism. While it still had ceremonies that resembled religious traditions, this was mainly done in mockery of organized religion, causing some historians to regard the cult as a "crude caricature of Catholic ceremonies" (Furet 564).

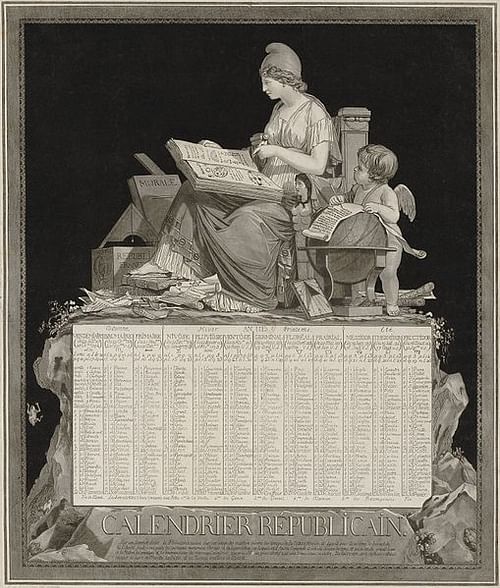

The Hébertists, who had come to power in the Paris Commune, sought to make de-Christianization an official policy of the Revolution and to make the Cult of Reason its official religion. They were instrumental in replacing many Christian symbols and statues with revolutionary iconographies, while the National Convention adopted the French Republican calendar, which erased all references to Christianity from the French year. Hébertist-aligned representatives brought this attitude into the provinces, having church properties vandalized and stripped of their valuables to fund the war effort. One representative, Joseph Fouché, robbed a cemetery of religious symbols and posted a sign on its gate that read, "Death is but an eternal sleep," which became a tenet of the Cult of Reason (Schama, 777).

The Cult of Reason was especially hostile to clerics themselves, who were humiliatingly forced to abjure their vows by getting married or to declare themselves to be charlatans, under threat of the guillotine. Outright violence against Catholics became increasingly common; Jean-Baptiste Carrier made a name for himself by submerging thousands of clergymen and religious Vendean rebels in the Loire River in the drownings at Nantes. On 7 November 1793, the Archbishop of Paris was forced to resign his duties and was made to replace his mitre with a red cap of liberty. To celebrate the archbishop's humiliation, the Hébertists organized a Festival of Reason to be held at the Notre-Dame Cathedral, which had been rededicated as the Temple of Reason.

The Festival of Reason, held on 10 November, was long the subject of scandalous rumor. It was true that Sophie Momoro, wife of one of the leading Hébertists, played a central role as the scantily clad goddess of Reason, and that the Christian altar was dismantled in favor of an altar to 'Philosophy'. Yet rumors persisted of acts of licentiousness, such as depraved orgies, that took place. True or not, these rumors finally forced the hand of Robespierre and the moralizing Jacobins.

Robespierre & Religion

By the end of 1793, Robespierre was reaching the summit of his dictatorial powers. Although all members of the Committee of Public Safety were theoretically equal, Robespierre controlled it in all but name, which made him the veritable master of France. Famously self-righteous and borderline puritanical, Robespierre had never been closer to achieving his vision of a perfectly virtuous Republic, consisting of citizens who thought of the greater good above all else. Standing in his way were the Hébertists and their seemingly hedonistic Cult of Reason. On a pragmatic level, Robespierre knew that their outspoken aversion to Christianity would further alienate the Republic from potential supporters and allies. On a personal level, he was offended by the cult's atheism and its rumored depravity, traits that were antithetical to his idealistic, moral society. Either way, he knew it had to go.

Not long after the Festival of Reason, Robespierre gave a speech in the Jacobin Club, denouncing atheism as 'aristocratic'. In March 1794, he arranged for the arrests and executions of nineteen leading Hébertists; their deaths also ensured the diminishment of the Cult of Reason. Immediately, Robespierre sought to undo the damage they had done, with his ally Georges Couthon announcing on 7 April that new proposals would shortly be brought forward for "channeling the spiritual leanings of the nation in more patriotic directions" (Doyle, 277).

But the question remained as to what exactly this new spirituality would look like. Despite his hatred of atheism, Robespierre was no fan of Roman Catholicism either, an institution that he largely viewed as corrupt. Instead, it was necessary to introduce a new god, one that personified the revolutionary values of truth, liberty, and virtue. Only through a shared faith in a higher power, Robespierre believed, could French society achieve its destiny and reach the pinnacle of virtue; clearly, he agreed with Voltaire that, "if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him" (Scurr, 294).

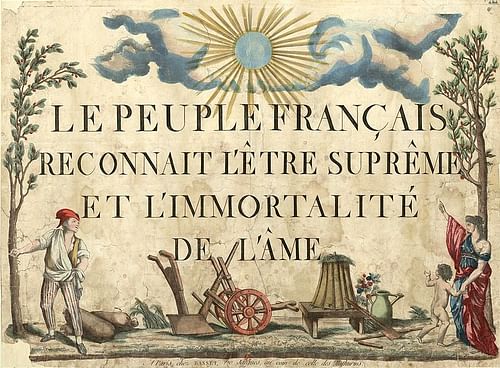

So, Robespierre set out to do exactly that. He established the Cult of the Supreme Being, which was centered around deism, the belief that a creator exists but refrains from interfering in the universe. Robespierre professed to believe in a Supreme Being as well as in the immortality of the human soul, preaching such doctrines before both the National Convention and the Jacobin Club. On 18 Floréal Year II (7 May 1794), he persuaded the Convention to officially establish the Worship of the Supreme Being; the opening lines of their decree proclaimed that:

1. The French people recognize the existence of the Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul.

2. They recognize that the worship worthy of the Supreme Being is the practice of the duties of man.

3. They place in the first rank of these duties [the obligation] to detest bad faith and tyranny, to punish tyrants and traitors, to rescue the unfortunate, to respect the weak, to defend the oppressed, [and] to do to others all the good that one can and not to be unjust toward anyone.

(Decree Establishing the Worship of the Supreme Being, from Alphahistory.com)

Republican celebrations were to be held every tenth day, or décadi in the new calendar, with the first large festival to be held on 20 Prairial (8 June), which also happened to be Whit Sunday in the old Christian calendar; whether this was merely a coincidence or a subtle challenge to the old religion is not known. In any case, the instructions the Convention sent out to the localities on how to prepare for the coming Festival were vague. Some areas adapted the props used in the recently proscribed festivals of Reason, simply painting over the atheistic slogans with the new deistic ones. Other religiously conservative areas used it as an opportunity to publicly perform Christian Mass for the first time since the start of the Terror, without fear of repercussion. But the focal point of celebration would take place just outside Paris itself, on the Champ de Mars.

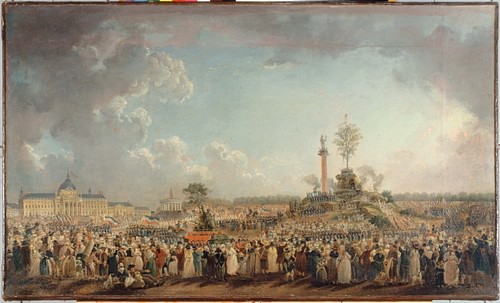

Festival of the Supreme Being

As the day of the festival approached, the renowned painter and fanatical Jacobin Jacques-Louis David was entrusted to organize the event. He constructed an artificial mountain on the Champ de Mars as the festival's centerpiece; it was a metaphor celebrating the triumph of the Mountain, the Jacobin's political party, over its enemies. David ensured that each celebration was meticulously choreographed, taking great pains to organize everything as efficiently as possible. The guillotine, which had been particularly busy as of late, was relocated from the Place de la Revolution to the site of the demolished Bastille, where the sound of the falling blade would be well out of earshot of the celebrating Parisians.

8 June 1794 proved to be a beautifully sunny day, as if the Supreme Being itself was smiling on the French people. Across Paris, citizens had decorated their homes with wreaths of oak and laurel, with tricolor ribbons and flowers. In the morning, they dutifully made their way to the gardens of the Tuileries Palace where the first of the day's celebrations and speeches were to be held. Watching the congregating masses from a room in the palace was Robespierre himself, dressed ostentatiously in a sky-blue coat, gold trousers, and a tricolor sash.

Since Robespierre had rather conveniently been elected president of the National Convention four days before, the responsibility fell to him to officiate the ceremonies and perform the duties of a high priest. He was much too excited to eat his breakfast, and according to his companion Joachim Vilate, he could hardly be drawn from the window, where he stood watching the assembly of laughing children, women wearing roses in their hair, and men with oak leaves in their hats. Marveling at this crowd that had gathered to celebrate a religion he had created, Robespierre mused to Vilate:

Behold the most interesting part of humanity! Here is the universe assembled before us! Nature, how sublime, how delightful thy power! How the tyrants must turn pale at the thought of this festival. (Scurr, 316)

At midday, Robespierre went out into the garden and joined his fellow deputies of the Convention. After quieting the crowd, Robespierre delivered his first speech of the day, which he began by announcing: "the day forever fortunate has arrived that the French people have consecrated to the Supreme Being" (ibid). Upon finishing his speech, he turned toward an ugly, misshapen cardboard statue that was supposed to represent Atheism, and lit it on fire. As it burned, it revealed another statue, this one beautiful and majestic, that represented Wisdom. Afterwards, Robespierre gave another speech during which he could hear the Convention deputies whispering and snickering behind his back. He would not forget the insult.

In the early afternoon, Robespierre led the crowd of singing citizens through the streets of Paris and to the Champ de Mars, where David's immense monument to Jacobinism loomed before them. Over half a million people were said to have gathered around it, shouting “Vive la Republique!” and “Vive Robespierre!” as the deputies took their seats at the summit of the mountain, next to a grand liberty tree. From on high, they led the assembled throngs in singing La Marseillaise and swearing the now customary revolutionary oaths. The rest of the day was filled with athletic competitions, in the spirit of ancient Greece. By most accounts, the Festival of the Supreme Being was the happiest day of Robespierre's life.

Reaction to the Festival

The Festival of the Supreme Being was well received by ordinary Parisians, who had become used to the flashy theatrics of revolutionary celebrations and enjoyed the excuse to let loose and forget the grim realities of France in 1794. Jacobin newspapers praised the festival as the finest day in the life of virtuous man, while in Orléans, another festival was held in which similarly jubilated crowds cried out, “Vive Robespierre!”

Of course, not everyone was happy with the festival, and many revolutionary leaders felt threatened by Robespierre's central role. By consolidating his power the previous winter and spring, Robespierre had already opened himself up to rumors that he aspired to total dictatorship; his role as chief pontiff of this strange new religion only seemed to confirm this speculation. One deputy of the National Convention, Jacques-Alexis Thuriot, thought as much. During Robespierre's grandiose speech in the Tuileries gardens, Thuriot whispered to a companion, "Look at the bugger. It's not enough for him to be master, he has to be God" (Doyle, 278).

Perhaps Thuriot and those who shared his thoughts were right to be worried; a mere two days after the Festival of the Supreme Being, Robespierre and his allies introduced a law to the Convention without prior consultation. This law, infamously known as the Law of 22 Prairial, was meant to solve the problem of Paris' overcrowded prisons by accelerating trials. Resulting from this was the month-long period of the Great Terror, during which over 1,400 people were rapidly guillotined in Paris.

Robespierre began to hint that he had a list of treacherous conspirators in the National Convention but kept refusing to name names, watching as the deputies squirmed beneath his shadow of Terror. Afraid that they had made the list, many deputies refused to sleep in their own beds, lest they be arrested in the dead of night. Finally, on 27 July 1794, members of the Convention rose up and overthrew Robespierre, who was executed the next day.

End of the Cult

With the fall of Maximilien Robespierre, the Cult of the Supreme Being largely fell into obscurity. Robespierre's central role in both the cult's creation and in the festival on 8 June meant that the cult was associated with him and his Jacobin movement. With his death, no one bothered to pick up the mantle. During the Thermidorian Reaction, the period that followed the Reign of Terror, the French government distanced itself from many Jacobin policies and customs, including the Cult of the Supreme Being. It was not until 1802 when Napoleon Bonaparte delivered the final death blow, officially banning both the Cult of the Supreme Being and the Cult of Reason with his Law on Cults of 18 Germinal Year X.

Robespierre had created the Cult of the Supreme Being to help bring about the virtuous society he had long envisioned. Yet the ideas surrounding the cult were much too vague to have any lasting effect, and Robespierre himself lacked the eloquence and charisma needed to attract followers to the religion. The Cult also failed because many associated it with Robespierre's personal ambitions and saw it as his attempt to claim divine, or at least dictatorial, status. The short life of the cult makes it impossible to know what Robespierre's long-term plans were for it, and leaves scholars to speculate whether it was meant to be just a political tool or a true deist religion.