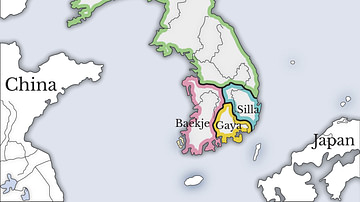

Choe Chiwon (857-915 CE) was a celebrated poet and scholar of the Unified Silla kingdom which ruled Korea from 668 to 935 CE. Choe Chiwon adopted the pseudonym or brush name 'Orphan Cloud' and he became the most celebrated scholar-official of his generation gaining valuable political experience in Tang China. Choe was a prolific writer, but unfortunately, only a small portion of his works survive. His poems are the oldest to survive in any great quantity from ancient Korea.

Early Life

Choe Chiwon was born into a reasonably well-to-do family of Head Rank 6 status in the Silla capital Gyeongju (Kyongju). He lived during the final decades of the Silla kingdom before it was replaced by Goryeo as the most powerful state in Korea. The Silla kingdom had long enjoyed close ties with the Tang dynasty of China (618-907 CE) and Choe, when he reached 12 years old, was sent to China to study, as was common practice at the time. At 18, Choe was given a post in the Tang provincial administration after he passed the extremely difficult civil service exam in 874 CE. Choe then, as was also typical of the time, kicked his heels for a few years while he awaited an official appointment. During this limbo, he received no pay but was still expected to perform menial clerk duties. He did, however, enjoy the impressive title which went with this waiting period of 'Gentleman for Rendering Service and General Purpose Censor Auxilliary.'

A Tang Official

Fortunately, the poet's early works gained the attention of the Tang court, and he was finally given a post in 879 CE. Choe was dispatched to act as a secretary to Gao Pian, a prominent official during the decade-long war to put down the rebellion led by Huang Chao. Choe's primary duty was to create posters to stir the public into condemning the rebels and assisting in their capture. In this task, he was able to show off his writing skills and ability to persuade. Choe also wrote poetry while in China, and in 886 CE a collection was published both in Korea and China. He made friends with contemporary Chinese writers like Ku Yun, Lo Yin, and Zhang Qiao but must have endured the difficulties of being a stranger in a foreign land for many of his poems from this period are concerned with sorrow, loss, and loneliness:

Don't think me strange gazing windward dispirited,

It's hard to meet a friend this far from home.

(Choe Chiwon, Seeing a Fellow Villager off in Shanyang)

He also produced a history on the founding of Balhae (Parhae), the Manchurian state, which he presented to the Tang court. The Huang Chao rebellion, though, would turn out to be the beginning of the end of the Tang dynasty and Choe returned to his native Korea in 885 CE as an official envoy of emperor Xizong.

Return to Silla & Retirement

Back at Silla Choe, now with valuable military and diplomatic experience, was made Vice-Minister of War. He also held the position of reader in attendance and appointed academic to the court. In 893 CE Choe was appointed envoy to China but did not go because dangerous rebellions had spread across the kingdom which meant he could not safely travel. In 894 CE he presented a memorial to the Silla queen Jinseong (r. 887-898 CE) formulating a set of administrative reforms, his 'Ten-Point Policy Recommendation,' but these were rejected. The Silla kingdom, like the Tang dynasty, was collapsing from within.

Choe then seems to have been frustrated by the rigid bone rank system of the Silla kingdom which limited the possibilities of promotion due to the status of his parents. Perhaps wisely, given the problems faced by the government to maintain its control over the state, Choe withdrew from public office at the capital and took up a position as local magistrate of Taesan prefecture in Chungcheong province. He then left administration altogether and dedicated himself to poetry, spending the rest of his days in the Buddhist temple retreat of Haeinsa in the mountains of Gyeongsang province. His body was enshrined in a Confucian temple, and in 1074 CE the state awarded him the honorary title of Marquis of Bright Culture.

Works

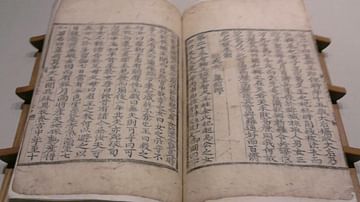

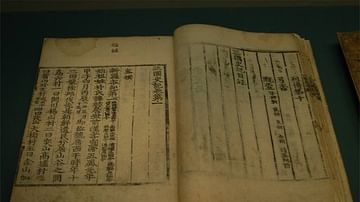

Choe Chiwon wrote a great number of essays on many themes, and his work displays a wide knowledge of Confucian principles, Buddhism, political administration, and poetry. Choe often wrote in the rich style of late Tang literature, something he was later criticised for, even if his works regularly appeared in anthologies printed after his death. He mostly wrote in 'parallel prose,' the highly stylised form of writing popular in China at the time, where lines are presented in couplets.

I only chant painfully in the autumn wind,

For I have few friends in the wide world.

At third watch, it rains outside,

By the lamp my heart flies myriad miles away.

(Choe Chiwon, On A Rainy Autmn Night)

Besides the 'Ten-Point Policy Recommendation' for Queen Jinseong, other known works include a historical chronology, the Chewang yondaeryok, the Chungsan igwe chip, a collection of essays, and the Sui chon, a collection of supernatural folktales from Silla. Besides those few printed volumes which survive by Choe, there are several long inscriptions made on stone. These latter are known as the 'four mountain inscriptions' and reflect the tradition of carving the achievements of great men on commemorative stones at temple and stupa sites. They were made by Choe himself and are, in addition to their historical content, an important record of Korean calligraphy. Choe's poems written while he was in China were collected into the 20-chapter, Kyewon-pilgyong ('Brush-pen Ploughings in Gardens of Cinnamon') and published in 1834 CE.

Dismounting on the sandbar I wait for a boat,

A stretch of smoke and waves, an endless sorrow.

Only when the hills are worn flat and the waters dried up,

Will there be no parting in the world of man.

(Choe Chiwon, At the Ugang Station)

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.