The Battle of Britain, dated 10 July to 31 October by the UK Air Ministry, was an air battle between the German Luftwaffe and British Royal Air Force and allies during the Second World War (1939-45). The Luftwaffe failed to achieve air superiority, necessary for any future invasion of Britain, and so the RAF won a precious victory that finally stopped the westward expansion of Nazi Germany.

The Fall of France

Germany attacked Poland on 1 September 1939, and so World War II began. German forces swept through the Low Countries and France in 1940. The British Expeditionary Force in France, cut off from the south of the country, was obliged to withdraw 340,000 men in the Dunkirk Evacuation of May-June. Paris was occupied on 14 June. The French government surrendered on 22 June. The unthinkable had happened, France had fallen, and it was now expected that the German leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) would next invade Britain in Operation Sea Lion. First, it was essential to establish air superiority if the invasion fleet was to safely cross the English Channel. The commander-in-chief of the German Air Force Hermann Göring (1893-1946) promised Hitler that his Luftwaffe would destroy Britain's air power by directly engaging fighter planes and bombing airfields and aircraft factories. As the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) told Parliament on 18 June: "The Battle of France is over. I expect the battle of Britain is about to begin" (Overy, 9).

Britain was hardly ready for the war that so swiftly came to its shores. In total, the RAF had lost 931 aircraft and suffered over 1,500 casualties in the defence of France, including the loss of over 500 pilots. The RAF desperately needed more pilots and aircraft to defend Britain in the coming months, which would prove to be a pivotal period of the entire five-year conflict. According to the secretary of Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding (1882-1970), the Commander-in-Chief of RAF Fighter Command, Dowding "said he knew full well he could never win the war but he was very conscious of the fact that he was the one man who could easily lose it" (Holmes, 132). The British people were already prepared for the worst. Thousands of children had been evacuated from cities, air raid shelters were being built in people's gardens, the blackout (where no non-essential lights were to show at night) was being enforced, and everyone carried gas masks. The question was where, when, and how would the Germans strike?

The Fighters

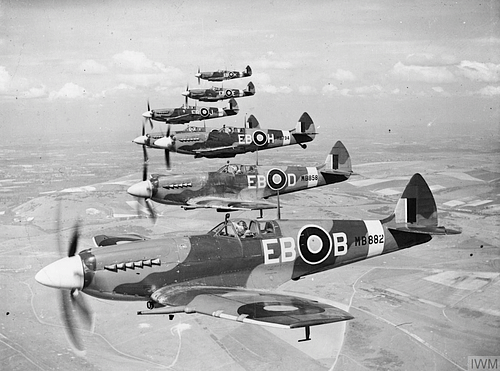

The two main fighters of the RAF in the summer of 1940 were the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane, both powered by Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. The Spitfire was the superior plane in terms of manoeuvrability and its top speed of 448 mph (721 km/h). The standard Spitfire armament was two machine guns (0.5 in / 12.7 mm) and two Hispano cannons (0.8 in / 20 mm). The Spitfire carried ammunition drums of 300-350 rounds for each machine gun, which meant that a pilot could only fire these for a total of 15 seconds. The RAF's second-best fighter was the Hurricane, but it had more of them than Spitfires. The Hurricane was reliable and well-armed with 8-12 machine guns.

The RAF had 19 Spitfire squadrons and 32 Hurricane squadrons in June 1940. These fighters and others like the Boulton Paul Defiant made a total operational force of around 600 fighters, pitifully few to defend Britain. Some thought that 120 squadrons were required, but this was impossible. In addition, Dowding was a cautious commander and rarely committed more than half of his force at any one time. Fortunately for Dowding, 300 new fighters were coming off the production lines each week. In addition, during the battle, 250 damaged planes were repaired back into service each week, a crucial statistic since up to 30% of planes were damaged by accidents as opposed to enemy fire. The Luftwaffe had a similar problem but was seriously disadvantaged here because their repair factories were far away in Central Europe.

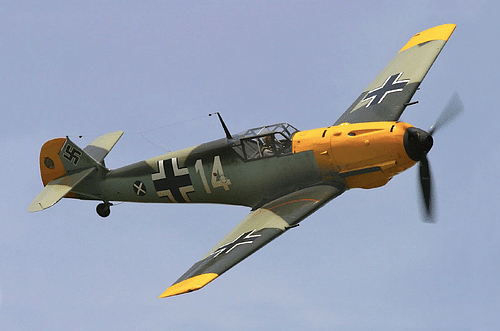

The Luftwaffe's main fighter was the Messerschmitt Bf 109 (Me 109), powered by a Daimler-Benz 12-cylinder engine. The Spitfire was more manoeuvrable than the Me 109, but the latter could dive better thanks to its fuel-injection engine. Both planes had a similar top speed. The German fighter was armed with a cannon and two machine guns. The Me 109 carried more ammunition than their RAF counterparts so the pilot could fire for 55 seconds in total. By 1940, over 150 of these fighters, known to their pilots as "Emils", were rolling off the production line each month. The Luftwaffe's second-choice aircraft was the slower Messerschmitt Bf 110 (Me 110) fighter-bomber. German fighters adopted the Schwarme formation where there were always two pairs of fighters together. All four planes were relatively spread out, which made the group much less visible than the tighter formation RAF fighters adopted early in the battle.

The Luftwaffe was numerically far superior to the RAF, but the historian M. Smith notes that the three Luftwaffe air fleets involved in the battle (Luftflotten 2, 3, and 5) could not, because of the distance involved, deploy all their strength: "In practice…the Luftwaffe would rely on a core of some 750 long-range bombers, about 250 dive-bombers, rather more than 600 single-engined, and 150 twin-engined fighters" (Dear, 124).

Home advantage was an important factor since the German fighters had far less time in the skies above Britain before their fuel ran out. The Germans could concentrate all their aircraft to the southeast of England, but, holding the tactical initiative, they could also keep the British guessing by continuously switching targets, both in terms of geography and type, such as Channel shipping, coastal towns, airfields, radar stations, and cities. In short, the RAF had to station fighters across Britain. A disadvantage for the Luftwaffe was that German airmen obliged to bail out and use their parachutes became prisoners of war. This was a battle where men were just as vital as machines, and training pilots and replacing losses became problematic for both sides, not so much in terms of bodies, but certainly in terms of experience flying the aircraft.

The Bombers

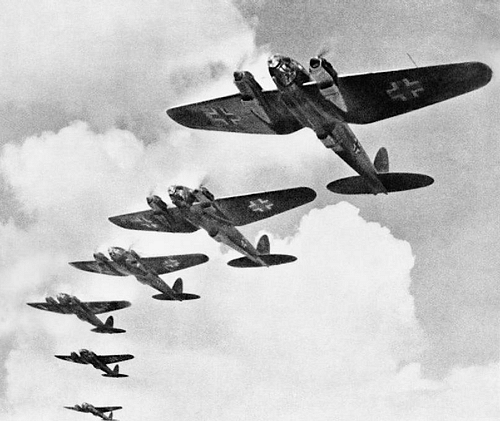

As the Luftwaffe sought to destroy the RAF on the ground, medium-sized bombers were deployed in the Battle of Britain. The Luftwaffe had rather ponderous bombers like the Dornier Do 17 and Do 215, but the Heinkel He 111 bomber was faster and more versatile. All German bombers were armed with machine guns, but they proved highly vulnerable to attacks from much faster enemy fighters, so much so that they needed a fighter escort and, in the end, were restricted to night flying. A major disadvantage for the Luftwaffe was the small bomb loads of these aircraft. The best bomber, the Junkers Ju 88, could only carry a maximum bomb load of 5,500 lbs / 2,500 kg (an RAF Lancaster bomber carried 14,000 lbs / 6,350 kg). A hybrid bomber was the Ju 87 Stuka, which had excelled at bombing specific targets during Germany's Blitzkrieg tactics in Western Europe so far in the war.

Luftwaffe bombers were guided to their targets by radar navigational aids. Knickebein ('Crooked Leg') sent two navigation-beam radio signals from Continental Europe, which the bombers could track. Where the two beams crossed marked where the bombs should be dropped. By August, the British knew of the system and sent jamming signals. An improvement to Knickebein was X-Gerät (X-apparatus) radar equipment, which followed several beams sent by transmitters in Continental Europe. Despite these aids, the bombing was often hopelessly inaccurate.

Pilots on both sides were young men, anyone in their thirties often got the nickname 'grandad'. The RAF fighter pilots included many from the British Empire nations and allies such as Poland and France. Many of these pilots had gained valuable experience in the Battle of France. The Luftwaffe pilots had greater experience since many had participated in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) as part of the Condor Legion. The Luftwaffe had also gained operational know-how with its attacks on Poland, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France.

A Total Defence System

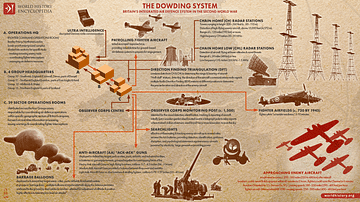

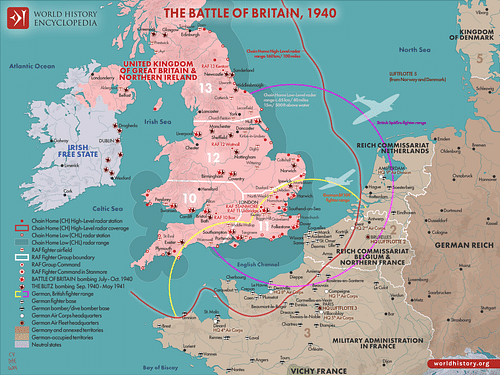

The British had prepared long before the battle by establishing the Dowding System, an integrated air defence system that allowed a speedy response to air attacks. The system involved Ultra intelligence code-breakers listening in to Germany's secret communications, RAF reconnaissance aircraft, and 30,000 volunteers of the Royal Observer Corps providing real-time updates on aircraft movements. Key to the system was radar (Radio Detection and Ranging), then called Radio Direction Finding (RDF). Radar consisted of towers built along the southern and southeast coast of England, with some located inland, too. There were three types: 20 Chain Home (CH) stations which could detect aircraft up to 100 miles (160 km) away, 30 Chain Home Low (CHL) stations which detected aircraft below 1,000 feet (300 m), and 24 MB2 mobile radar units. Radar permitted RAF HQ to know where and when the Luftwaffe were attacking. These radar towers proved difficult to bomb and relatively easy to repair, but the Luftwaffe never went for a concentrated attack on these vital structures.

Fighter HQ collected data and then sent signals to scramble fighter squadrons, alert searchlight, barrage balloon, and anti-aircraft crews around the country, and warn civilians in the way of harm via the police and Air Raid Precaution volunteers.

The Dowding System depended on speed to be useful. German fighters could cross the Channel in six minutes and bombers could reach the closest airfields in 11 minutes. Britain would also be attacked from Luftwaffe bases in Scandinavia. It took the British fighters up to 20 minutes to assemble and reach the necessary altitude, meaning that the German fighters were often ready and waiting for them. The Luftwaffe also made frequent use of diversionary raids, which drew off fighters from the main raiding force. The battle would be finely balanced, with both sides never sure of the enemy's losses.

Eagle Day

The battle began in June, with the Luftwaffe concentrating on raids on merchant shipping in the English Channel, hoping to tempt out the enemy fighters and then hit them in numbers. There were, too, a few raids on coastal ports through July, but most of these engagements were small-scale.

13 August was Adlertag ("Eagle Day"), the first day of Unternehmen Adlerangriff ("Operation Eagle Attack"). This is when the Luftwaffe began what Göring promised to be a two-week obliteration of the RAF by systematically attacking airfields and installations and overwhelming aircraft in the air. For German historians, this day is the beginning of the Battle of Britain. Around 1,800 bomber and fighter sorties were launched in two days along the entire coast of England from Northumbria to Dorset. The weather was not helpful to the attackers, and on 15 August, the Luftwaffe felt the robustness of the British defence, losing 75 aircraft compared to the RAF's 34 losses. From 19 August, Göring ordered his fighters to concentrate on engaging their RAF counterparts in the air. As a result, in this phase of the battle, and perhaps uniquely in the entire war, a few hundred young men on each side were determining the course of the conflict while the world looked on.

The Tide Turns

Britain's skies were sometimes saturated with aircraft, but the battle between fighters remained a series of one-on-one duels, as described by Wing Commander 'Max' Aitken:

Although there were a lot of aircraft about suddenly, when you were fighting a particular man, him in his machine and you in your machine, the sky became empty and you didn't see anyone else, you saw nothing except this one man you were trying to shoot down and he was trying to shoot you.

(Holmes, 136)

In the latter stages of the Battle of Britain, Spitfires and Hurricanes were used as a single tactical unit of 60 aircraft, a formation known as a 'Big Wing'. The idea was championed by Trafford Leigh-Mallory (1892-1944), who commanded the No. 12 Fighter Group protecting the industries of the Midlands. The blow a 'Big Wing' could produce was much greater than that of scrambling a single squadron, but it took time to assemble the formation, and so, typically, enemy bombers had already hit their targets before the fighters got to them. Another disadvantage was that having fighters involved in a 'Big Wing' meant none were defending the airfields of other fighter squadrons that had scrambled.

Luftwaffe bombers continued to strike but were often let down by the quality of the bombs. Incendiary bombs could help mark a target for other bombers, but these were so light they often drifted badly. This meant that bombers following in on the attack continued to hit wayward of the mission target. In addition, the decision by the Luftwaffe back in the 1930s not to develop four-engined heavy bombers now proved significant. Even the famed Stuka dive-bomber turned out to be a huge disappointment when it was shown to be highly vulnerable to enemy fighters. Eventually, the Stuka was withdrawn from the battle. In short, the bombers were not delivering the knock-out blows Göring had hoped for.

German bombers might have been on the light side, but they could still cause carnage. A small group of He 111s bombed London on the night of 24 August 1940. They had been sent to hit an oil terminal but mistakenly hit the city, thus beginning a tit-for-tat bombing of civilian areas that escalated for the remainder of the war. The RAF bombed Berlin on the night of 25 August, and the Luftwaffe sent 300 bombers to hit London on 7 September. A significant downside of the Luftwaffe's increased use of bombers was that their fighters had to escort them, and this reduced their great strengths of speed and manoeuvrability. RAF bombers were active during the battle, attacking the barges accumulated in France ready for an invasion and hitting German airfields.

The battle became one of attrition, with neither side achieving total domination and both overestimating their enemy's losses. The latter failure particularly affected the Luftwaffe since, believing Fighter Command was at the very limit of its resources, Göring ordered bomber groups to attack day and night, but in doing so, he committed too many of his own aircraft against an enemy that was, in fact, as strong as at any point in the battle. The Germans also suffered from not having a clear strategy of just how and where to attack the enemy. Both sides lost an alarming amount of aircraft and men in the closing days of August and the first week of September. It now became a question of who could replace their resources better, and here the British had a strong advantage.

At the end of August, RAF airfields were mercilessly bombarded. From the second week of September, the Luftwaffe made the fateful decision to switch targets again, this time to cities, perhaps in the mistaken belief that the RAF was down to its last few hundred aircraft and that, by crushing civilian morale, the battle and even the Western war might be ended. In the end, the Luftwaffe launched over 3,000 bombing raids against Britain killing 27,000 civilians.

Victory

The decision to bomb cities was a heavy blow for civilians, but it was a strategically unimportant target in terms of gaining air superiority, the original aim of the battle. The decision ensured the RAF had a clear target: the bomber squadrons, especially since the diversionary raids were halted. On 15 September, often called 'Battle of Britain Day', the RAF shot down around 60 aircraft. That made 175 German aircraft losses in eight days. The losses were unsustainable, especially as aircraft would be needed to protect an invasion fleet and for use elsewhere in the war such as Hitler's planned attack on the USSR. On 17 September, Hitler postponed Operation Sea Lion.

The RAF's total aircraft losses in the Battle of Britain were 788 compared to the Luftwaffe's 1,294 (Dear, 127). The general proportional difference in losses was around 6:10 in favour of the RAF (the difference being Luftwaffe bombers). In the battle, Spitfires shot down 529 enemy aircraft while 361 Spitfires were lost (Saunders, 27). It was the old warhorse the Hurricane that contributed more to the victory, though: "Hurricanes destroyed more enemy aircraft than all other defences, air or ground, combined" (Mondey, 152). Britain had won, and the RAF had maintained air superiority, but the price was high. 2,927 RAF pilots participated in the battle; 554 were killed. As Churchill famously stated, "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few" (Overy, 74).

Crucially, the RAF ended the battle stronger overall than it had started. The Luftwaffe more or less maintained its aircraft strength, but the price for air superiority had proved too high to pay, and the number of pilots it could call upon was a third less than at the start of the battle. The Luftwaffe continued to attack Britain, focussing on night-bombing British cities, including the London Blitz. The RAF gained revenge for these attacks when they conducted the Allied strategic bombing of Germany, a strategy maintained for the rest of the war until Germany was finally defeated in 1945.