According to the Bible, Nehushtan was a metal serpent mounted on a staff that Moses had made, by God's command, to cure the Israelites of snake bites while wandering in the desert. The symbol of snakes on a staff or pole is a motif that is widespread in both the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean. This symbol held such cultural power that it is still around today in our modern world, like other ancient symbols we encounter almost daily, often without even realizing it. Humanity has a way of collecting images and holding onto them, subtly changing their context to fit the contemporary cultural system.

In our modern world, a staff with a snake wrapped around it is used as a symbol for medicine, a remnant of Greek and Roman mythology. It is the staff of an ancient healer god, known as Asklepios in Greece and Aesculapius in Rome. Another symbol from ancient Greece and Rome is the staff of Hermes/Mercury (respectively) which is seen on the back of ambulances. This symbol is a pole with two snakes wrapped around it and wings at the top. While both are often called a caduceus, technically only the staff of Hermes/Mercury is a caduceus. Additionally, both are often assumed to be medicinal in nature, but Hermes/Mercury was a messenger god known for speed and escorting the dead to the afterlife. One can easily see the connection between our modern use of these symbols with their sources from ancient Greece and Rome.

Moses & the Snake

The story of the biblical snake on a staff is first introduced in a brief couple of verses in Numbers 21, during the Exodus story. This passage is believed to have been written by the E source, in approximately 850 BCE. (For an explanation of biblical sources, see “Torah”.) The Israelites, while traveling to the Promised Land from Egypt, complained about the lack of food and water and, as punishment, God sent fiery serpents to bite and kill many of them. The people then pleaded with God for mercy and, deciding to grant it, God instructed Moses to create a serpent and put it on a pole. When people would look at it, it would cure them of their poison. Moses complied and made the serpent out of nechôsheth, which means bronze, brass, or copper in Hebrew. From here on, this text will use “copper” as the translation.

This narrative is reminiscent of ancient Canaanite sorcerers who would fight alongside serpents to protect people from snakes and scorpions, as described in texts found from Ugarit. These texts also included a large portion of spells which were used to cure snake bites. This incident in the exodus story is quickly passed over in the Bible, and this snake is not heard of again until 2 Kings 18 when King Hezekiah of Judah (who reigned from either 727-698 or 715-687 BCE) destroys it because it had by that time become a pagan cult object. It is also in this passage that it is given the name Nehushtan. Hezekiah destroyed many cult objects and places in an effort to reform the Israelites back to monotheism as they were slipping into idolatry and paganism. It is unknown how the object came to have a proper name.

Translation & Philology

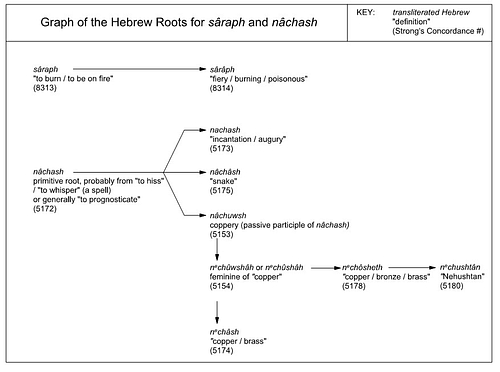

The philology and translation of some of the Hebrew words in this discussion is both fascinating and complicated, yet it is necessary to begin to decode the meaning of Nehushtan. (The Hebrew words in this article were extracted from the Interlinear Bible on BibleHub.com, which uses the Westminster Leningrad Codex.) In Numbers 21:8, God orders Moses to make a sârâph, which derives from sâraph, a verb meaning “to burn” or “to be on fire”. Technically, in this verse, God told Moses to create a “fiery (or burning) one”. It is often figuratively translated to mean “poisonous one”, as conveyed in Strong's Concordance. Although in all other contexts, aside from being paired with snakes, it is translated as “burning” or “fiery”. In verse 6, it was “fiery serpents” (nechâshim serâphim) which were plaguing the people, and in verse 9, Moses creates a copper serpent (nâchâsh nechôsheth). This makes the order of appearance: fiery (poisonous) serpents, a fiery one, and a copper serpent.

It is often assumed that, because according to the text the object did indeed heal people, Moses had created it according to God's specifications and therefore a “fiery one” was a serpent. However, that is a bit of an assumption, albeit a fairly common and accepted one. There are passages in Isaiah where the serâphim (standing alone without nechâshim) are also listed under “serpent” in Strong's Concordance. While the words do seem to correlate, it seems too simplistic to interchange them. As stated above, Numbers is believed to have been written roughly around 850 BCE. In Isaiah 6, 14, and 20, sârâph and serâphim are used with other mythological descriptions such as flying or with wings and feet. Isaiah 14 and 30 is believed to have been written no earlier than the mid-6th century BCE while Isaiah 6 may have been written as early as the late 8th or early 7th century BCE.

While we know that snake cults did exist in the ancient Near East, as of yet there does not seem to be an overwhelming amount of archaeological material to explain if there was a cultural reason why there is a linguistic connection between snake and augury. Two examples of material artifacts for such cults include an Iron Age ceramic stand with snakes slithering up it from Beth Shean and a copper snake with a gilded head from Timna. Perhaps there was a specific form of divination using snakes which made the two words inextricably linked.

It is important to note that the original Hebrew did not have written vowels. Nâchash (“to whisper”), nachash (“incantation”), and nâchâsh (“snake”) originally did not have any written difference. One could question whether there was a vocal difference, but the linguistics seem undoubtedly connected, so too there may have been a cultural context. Throughout the rest of the Hebrew Bible, both nâchash and nachash are heavily condemned and grouped with other evils such as child sacrifice and wizardry. (See Genesis 30:27, 44:5, and 44:15, Levicitus 19:26, Deuteronomy 18:10, 1 Kings 20:33, 2 Kings 17:17 and 21:6, and 2 Chronicles 33:6.)

Sea Monsters & Chaos

In addition to their association with “burning”, serpents were the monsters of the sea in the Bible, sometimes with multiple heads, and were great primordial fiends trampled on by God. A common polytheistic approach to dealing with primordial evil was a great cosmic battle in which a benevolent god fought and conquered over the monsters of chaos (often associated with water and/or the sea). While the Bible's view of inherent good in the cosmos differs from the surrounding pagan view of inherent evil and chaos, the Bible does borrow the cosmic battle motif from surrounding cultures. These verses contain some examples: Isaiah 27:1, Isaiah 51:9, Job 26:13, Psalm 74:13-14, Psalm 77:16, and Job 26:13.

Although the snake was often used in the ancient Near East as a symbol of fertility and blessing, it was also seen quite frequently as a monster being defeated by a god, often the storm god. In the ancient Ugaritic texts, supernatural entities could be largely divided into benevolent and destructive entities. Destructive deities were primarily animal gods, monsters, and undomesticated animal species which included snakes and serpents, while the benevolent deities were anthropomorphic and domesticated animals, such as the bull, calf, bird, and cow. This cosmic battle between a benevolent god and evil snake is seen throughout the ancient Near East, over thousands of years.

Another example of this cosmic battle from Babylonian mythology is hinted at in Genesis 1. In the Babylonian creation epic the Enuma Elish, Tiamat is the goddess of saltwater who wages war on the gods for killing her consort Apsu (god of freshwater). Marduk becomes the hero of the gods because he is the only one able to defeat Tiamat. Interestingly in Genesis 1:2, the Hebrew word for “deep” is tehom, a direct translation of “Tiamat”. Tehom is never used with a definitive article in the original Hebrew, suggesting a relationship to a proper name. This word is also used in mythological battle contexts in the Bible, such as in Habakkuk 3:10, where it is listed as one of the forces of nature fought by God. There can be almost no doubt that Genesis 1 contains remnants of the Enuma Elish.

The Garden of Eden

The story of the snake (nâchâsh) in the Garden of Eden in the 3rd chapter of Genesis hardly needs an introduction; however, there are some interesting things to point out. In verse 14, when God is cursing the snake, He says, “upon your belly you shall go, and dust you shall eat all the days of your life.” This implies that the snake was not on his belly and therefore, in one way or another, not on the ground. Perhaps the snake was in a tree. This interpretation fits in nicely with our snake-pole symbol, but it must be pointed out, that with the other connections to sea-serpents and to wings (as with the serâphim), being on the tree is not the only explanation for the snake not being on the ground. Although it does seem to be a reasonable explanation, as this particular nâchâsh does not have any other mythical descriptions attached to it, aside from it being able to speak.

Snakes on Staffs in Egypt

Before the poisonous snake incident in the desert with Moses, while the Israelites were still in Egypt in Exodus 7, Aaron threw his staff down before Pharaoh and it turned into a snake. This was a miracle given by God to show Moses and Aaron's authority to Pharaoh. (A test of this miracle was performed by Moses in Exodus 4, before returning to Egypt to free the Israelites.) The Pharaoh's sorcerers were capable of the same miraculous feat but Aaron's staff ate the others. In the text, it is technically the “staff” that ate the other “staffs”. We are not told when the snakes turned back into staffs or how this devouring occurs.

This event may appear to be a random act for those unfamiliar with Egyptian archaeology; however, the idea of a serpent staff was common throughout Egypt. Ancient Egyptian artwork contains presentations of serpent staffs, including the gods Thoth, Nehy, and Heka holding them. Snakes and other animals such as crocodiles and scorpions were used in ancient Egypt to protect against venomous animals. Serpent symbolism in ancient Egypt is very diverse and is also associated with the gods Apophis, Hathor, Isis, Mehen, Meretseger, Nehebkeu, Nephthys, Renenutet, Shay, Wadjet, Wenut, and Werethekau.

Snakes on Staffs in Mesopotamia

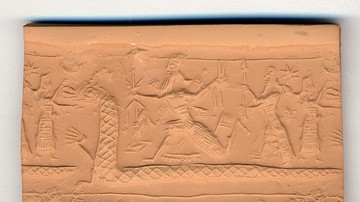

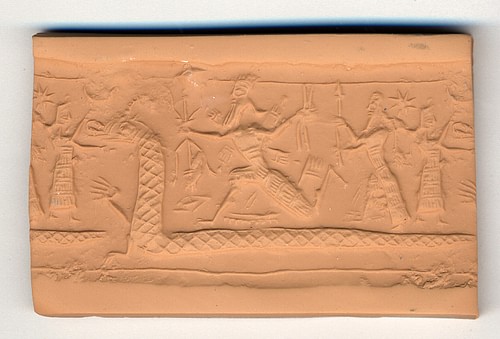

In ancient Mesopotamia, entwined serpents on poles were represented from early Sumerian and Neo-Sumerian times all the way through the 13th century BCE. A perfect example of this can be from the Sumerian city-state of Lagash where a vessel was found that was dedicated by King Gudea in the 21st century BCE to the Sumerian god Ningishzida. On this vessel is an image of two snakes wrapped around a pole.

Ningishzida was a chthonic god, associated with the cult center at Gishbanda in southern Sumer. In later Babylonian times, both Ereshkigal, queen of the netherworld, and Ningishzida were associated with the constellation of Hydra, which the Babylonians visualized as a snake having lion paws in front, wings, and a head reminiscent of a mušḫuššu dragon. Mušḫuššu dragons were long used as symbols for various gods and as protective agents from the Akkadian Period into Hellenistic times. The mušḫuššu dragon had the head and body of a snake with horns, lion feet in the front, and bird feet in the back.

Perhaps these representations of Ningishzida are the origin of Nehushtan. While separated by a large expanse of time, the common symbolism is uncannily striking. One more piece of evidence potentially connecting the two is the etymology of the name Ningishzida, which means “Lord of the Good Tree”. In addition to the visual similarities, there is also this linguistic connection between the snake god and a tree, as seen in Genesis. If it were proven that Ningishzida has a direct link to Nehushtan, we would still have to wonder whether this snake-staff motif in Numbers was used because of previous knowledge of Ningishzida at the time of Moses or if the evolution of the snake-staff into the deity Nehushtan in 2 Kings was influenced from the Ningishzida myth possibly known to the Israelites at that later time.

Conclusion

There is a patchwork of connectedness across the ancient Near East that gives context to the mystery of Nehushtan, although few definitive answers. The peoples of the ancient Near East were diverse, but they frequently embraced similar motifs. While correlations are easily presented, there may always be a mystery about how snakes, staffs, copper, fire, and sea monsters became intertwined.