The history of the second Persian war as presented in most of the modern literature is solely based on Herodotus' Histories. However, Herodotus' narration seems to contain several unrealistic elements which raise doubts about the actual strategy of the Greek alliance. In this article we present an alternative interpretation of Herodotus' story by using the information derived from an inscription found on a marble tablet of the 3rd century BCE. This inscription is known as the “Decree of Themistocles” or the “Decree of Troezen” from the name of the small city in Argolis, Greece, where it was discovered.

The most striking weaknesses in Herodotus' story are the following:

- Athens which was a city of about 100,000 inhabitants was evacuated in just one week.

- Similarly, the Peloponnesians were able to build a wall about 6km long along the Isthmus in just one month following the battle of Thermopylae.

- The Spartan king Leonidas was sent to Thermopylae commanding a small army of about 6,000 hoplites including 300 Spartans to stop the Persian advance. This mission appeared almost suicidal if the size of the two armies were compared (the Persian army was at least 300,000 strong). This would be very unusual for the Spartan mentality since Spartans were very cautious to avoid unnecessary casualties and never attempted hopeless missions.

These difficulties in the historical analysis indicate that the Greek strategy as presented by Herodotus is not exact. However, there was no other alternative historical source to contradict Herodotus, so his story of the Greco-Persian wars was widely accepted without doubts.

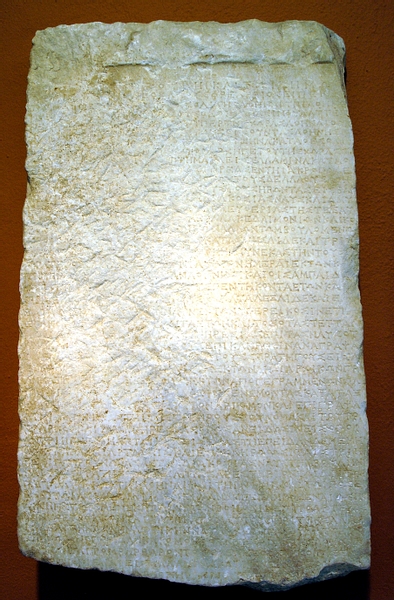

Recently another possible source of information on the Greek strategy was discovered. In 1959, at the small city of Troezen at the Argolic coast, South of Athens across the Saronic Bay, M.H. Jameson, who was an archaeologist working in the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, discovered a marble tablet on which the following Decree of the Athenian Assembly was carved (Jameson, 1960):

Gods.

Resolved by the Vouli and the People.

Themistocles son of Neocles of Phrearrhioi made the motion.

The city shall be entrusted to Athena, Athens' protectress, and to the other gods, all of them, for protection and defense against the Barbarian on behalf of the country.

The Athenians in their entirety and the aliens who live in Athens shall place their children and their women in Troezen, [to be entrusted to Theseus ?] the founder of the land. The elderly and movable property shall for safety be deposited at Salamis. The treasurers and the priestesses are to remain on the Acropolis and guard the possessions of the gods.

The rest of the Athenians in their entirety and those aliens who have reached young manhood shall embark on the readied two hundred ships and they shall repulse the Barbarian for the sake of liberty, both their own and that of the other Greeks, in common with the Lacedaemonians, Corinthians, Aeginetans and the others who wish to have a share in the danger.

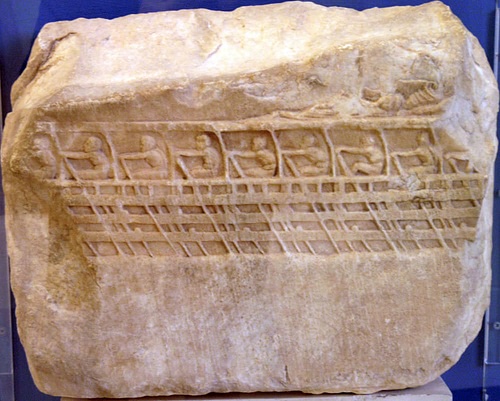

Appointment will also be made of trierarchs, two hundred in number, one for each ship, by the generals, beginning tomorrow, from those who are owners of both land and home in Athens and who have children who are legitimate. They shall not be more than fifty years old and the lot shall determine each man's ship. The generals shall also enlist marines, ten for each ship, from men over twenty years of age up to thirty, and archers, four in number. They shall also by lot appoint the specialist officers for each ship when they appoint the captains by lot. A list shall be made also of the rowers, ship by ship, by the generals, on notice boards, with the Athenians to be selected from the lexiarchic registers, the aliens from the list of names registered with the Polemarch. They shall write them up, assigning them by divisions, up to two hundred divisions, each of up to one hundred rowers, and they shall append to each division the name of the warship and the captain and the specialist officers, so that they may know on what warship each division shall embark.

When assignment of all the divisions has been made and they have been allotted to the warships, all the two hundred shall be manned by order of the Vouli and the generals, after they have sacrificed to appease Zeus the All-powerful and Athena and Victory and Poseidon the Securer. When they have completed the manning of the ships, with one hundred they shall bring assistance to the Artemision in Euboea, while the other hundred shall, all around Salamis and the rest of Attica, lie at anchor and guard the country.

To ensure that in a spirit of concord all Athenians will ward off the Barbarian, those banished for the ten year span shall leave for Salamis and they are to remain there until the people decide about them. Those who have been deprived of citizen rights are to have their rights restored.

The marble tablet was dated to be Hellenistic. Therefore, if genuine, it was copied from an original papyrus about 200 years after the Decree was approved by the Assembly of the People of Athens. The inscription clearly states that the Athenians abandoned their city before the battle of Artemision. Specifically, it is stated that Athens was evacuated at about the same time as the navy sailed out of Athens to get its position in Artemision. This probably means May 480 BCE.

There are many arguments against the validity of this inscription based on some differences between the strategic plan described in the Decree and the one which is supposed to be presented by Herodotus in the Histories. However, if the discrepancies of Herodotus' narration are carefully analysed, the Decree can be shown to be helpful in resolving them in a consistent and logical way. More specifically Herodotus indirectly gives information about a strategic plan similar to the one described in the Decree through the Delphi oracles he reports:

For when some emissaries sent from Athens to Delphi entered the temple and took their places (after having performed the prescribed rites in the sanctuary and generally prepared themselves to consult the oracle), the Pythia, whose name was Aristonice, gave them the following prophecy:

Fools, why sit you here? Fly to the ends of the earth,

Leave your homes and the lofty heights girded by your city.

The head is unstable, the trunk totters; nothing—

Not the feet below, nor the hands, nor anything in between—

Nothing endures; all is doomed. Fire will bring it down,

Fire and bitter War, hastening in a Syrian chariot.

Many are the strongholds he will destroy, not yours alone;

Many the temples of the gods he will gift with raging fire,

Temples which even now stand streaming with sweat

And quivering with fear, and down from the roof-tops

Dark blood pours, foreseeing the straits of woe.

Go! Leave my temple! Shroud your hearts in misery!

These words completely disheartened the Athenian emissaries. The doom foretold for them plunged them into utter despair, but then Timon the son of Androbulus, who was one of the most distinguished men in Delphi, suggested that they should go back, this time with branches of supplication, and consult the oracle again, as suppliants. The Athenians took his advice and said to the god, 'Lord, please respect these branches with which we come before you as suppliants, and grant us a more favorable prediction for our country. Otherwise we will never leave your temple, but will stay right here until we die.' At this request of theirs the oracle's prophetess gave them a second prophecy, which went as follows:

No, Pallas Athena cannot placate Olympian Zeus,

Though she begs him with many words and cunning arguments.

I shall tell you once more, and endue my words with adamant:

While all else that lies within the borders of Cecrops' land

And the vale of holy Cithaeron is falling to the enemy,

Far-seeing Zeus gives you, Tritogeneia, a wall of wood.

Only this will stand intact and help you and your children.

You should not abide and await the advance of the vast host

Of horse and foot from the mainland, but turn your back

And yield. The time will come for you to confront them.

Blessed Salamis, you will be the death of mothers' sons

Either when the seed is scattered or when it is gathered in.

This oracle was less harsh than the previous one, and that is certainly what the emissaries thought, so they had it written down and then returned to Athens. (Herodotus VII.140-142)

The two oracles were fundamentally different. The first one was a general comment confirming the unquestionable superiority of the Persian forces. The second one contained interesting details of the Athenian strategy, which was finally implemented. In particular, it specified the main weapon of the final battle, the navy (“a wall of wood”), its place, Salamis, and its time, late September (“when the seed is scattered”). Interestingly, a second option for the time is specified but with a smaller probability (“or when it is gathered in”) meaning the following spring. Modern historians expressed the theory that the second oracle was invented retrospectively by Herodotus, who was a warm supporter of Delphi and their oracles.

How was it possible that the Delphi priests knew Themistocles' strategy? The most reasonable explanation lies with the procedure the Athenian envoys followed after the first oracle. It is certain that the Athenians as suppliants requested to present their arguments against the first oracle. This could only be done if at least some key elements of the Athenian strategy were revealed to the priests; although it is expected that critical details were kept secret. The second oracle was a result of negotiations and consultations between the Athenian envoys and the priests. After all, the Delphi priests were interested in issuing oracles not far from reality, so they were open to such negotiations, which would help them to have a more complete view of the plans of the parties involved. Therefore, the second oracle included elements of the actual Athenian strategy which roughly agree with the strategy declared in the Decree.

Moreover, there is an additional excerpt from Aristotle' “Athens Constitution”, which further confirms the validity of the Decree:

Three years later, however, in the archonship of Hypsichides, all the ostracized persons were recalled, because of the advance of Xerxes' army; (Aristotle 22)

Therefore, Athens Constitution agrees with the text of the Decree that the ostracized persons were recalled when Archon was still Hypsichides, well before the battle of Salamis, which took place in the archonship of Calliades.

Another argument in support of the Decree concerns the expedition of the Greek forces to Tempe presumably to defend Thessaly. As Herodotus narrates, the Greeks army under the command of the Spartan Euaenetus and Themistocles landed in the harbour of the small Thessalian city Alos in the Pagasae Bay and then marched to Tempe abandoning their ships there. Such an expedition would require a second Greek force to protect the ships. Looking at the map, Alos is just 16 nautical miles (about 30 kilometres) away from Artemision. Therefore the army which took part in the expedition to Tempe was dispatched from the Artemision camp. It was probably half of the Greek force which marched to Tempe, while the other half remained in Artemision guarding the entrance of the Pagasae Bay and the ships which were left at Alos. If the expedition to Tempe took place in June, then the establishment of the Artemision camp took place in May. Therefore Athens was evacuated at about the same time.

Hence, the Decree of Troezen was probably voted by the Assembly in the spring of 480 BCE, not in the summer. All this information converges to substantiate the fact that the Athenian strategy was developed very early in the war. This gave the Greeks a great strategic advantage.

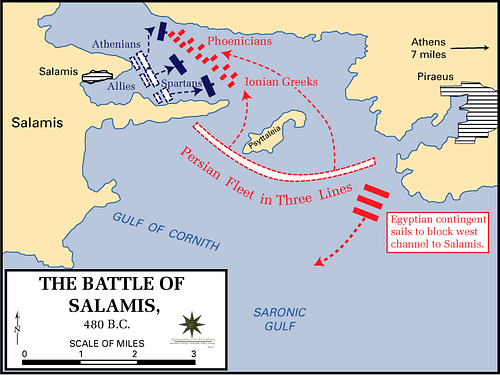

Which exactly was the Athenian strategy designed by Themistocles? The main elements of Themistocles' strategy are summarized as follows: All Athenians would go onboard the ships to fight in the sea. The navy would be divided into two fleets. One would remain in Attica to protect Salamis, and the second would engage the enemy at Artemision. The main battle was planned to take place in Salamis toward the end of September.

Therefore, the Decree of Troezen is not only compatible with several elements of Herodotus' narration but also helps to interpret the Histories in a more realistic and plausible way.