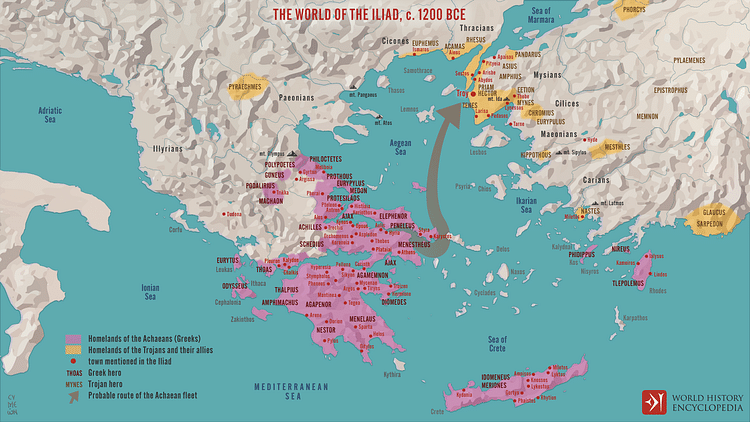

In his epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, the Greek poet Homer (c. 750 BCE) told the story of the Trojan War, a ten-year siege of the city of Troy by an alliance of Greek city-states. Troy was also known by its Latinised name of Ilium and was located on the northwest coast of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey).

The city was continuously inhabited from the Early Bronze Age (c. 3000-2200 BCE) for around 4,000 years until two major earthquakes destroyed Troy in 1300 CE, and it fell into decline. Archaeological finds suggest that a small Byzantine community lived at Troy in the 12th century CE, but the powerful kingdom of Homer's epics was lost to history, although it remained in the popular imagination.

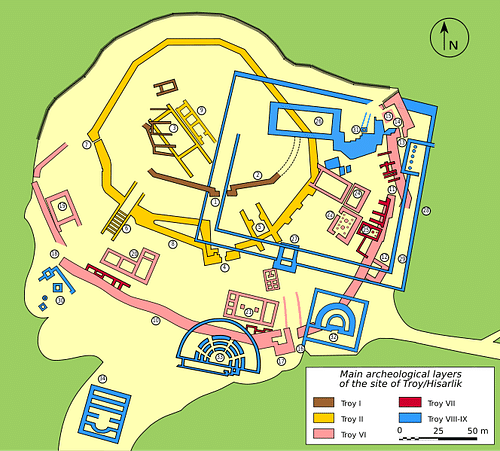

In the 19th century, Hisarlik was widely believed to be the site of ancient Troy. Its location on a hill near Tevfikiye in the Dardanelles, which connects the Aegean to the Black Sea, was a strategically important position because it commanded a major trading route. Archaeologists started to excavate the strata or layers of the different settlements, which, over time, had formed a mound or tell 20 m (65 ft) in height, and these layers are labelled Troy I to Troy IX. To date, nine cities and 46 levels of occupation have been unearthed, showing that there was no single Troy but a succession of civilisations that occupied the area.

Whether the Trojan War was a Late Bronze Age (c. 1700-1000 BCE) historical event or merely Greek mythology remains the subject of scholarly debate, but the city of Homer's Iliad is generally accepted to have been found and is associated with three famous archaeologists: Heinrich Schliemann, Wilhelm Dörpfeld, and Carl Blegen.

Heinrich Schliemann: Finding & Almost Losing Troy

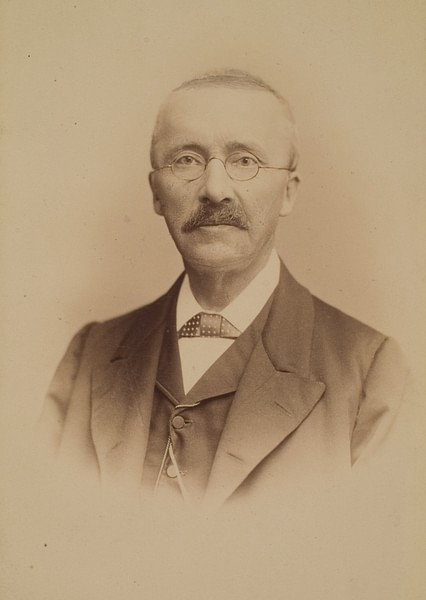

Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann (1822-1890) achieved worldwide fame in 1873 when he claimed to have discovered Troy. Schliemann was a German businessman and a pioneer archaeologist (although untrained) who was fascinated by the idea of Troy after seeing a picture of the city burning in a book entitled Weltgeschichte für Kinder ("World History for Children") when he was seven years old.

The son of an impoverished Lutheran pastor and the fifth of seven children, Schliemann was an extraordinarily gifted linguist who spoke more than 15 languages and started travelling at an early age. He wanted to emigrate to South America and took a position as a cabin boy on board a vessel bound for La Guajira, Colombia, that was wrecked off the Dutch coast in 1841. He stayed in Amsterdam and worked as a bookkeeper for a city merchant, learning French, Dutch, and English – the main trading languages.

In 1846, Heinrich Schliemann became an agent for the German trading house B. H. Schröder & Co. and was sent to Saint Petersburg because he was the only Russian-speaking employee. This was the start of Schliemann's accumulation of his fortune, trading in indigo dye and saltpetre before arriving in California in 1851 and turning a multimillion-dollar profit during the Gold Rush.

Heinrich Schliemann retired in 1858 at the age of 36, having returned to Europe and marrying his first wife, Russian-born Ekaterina Petrovna Lyschin (1826-1896). He spent his time touring classical archaeology sites, and in 1868, Schliemann met Frank Calvert (1828-1908), a British expatriate diplomat whose Levantine English family owned land in Hisarlik, which included the eastern half of the Hisarlik mound (the western half belonged to the Turkish government).

Calvert studied the site, excavated trenches, and was convinced he had found Homeric Troy, but he lacked the finances to conduct further digging seasons. Calvert invited Schliemann to dinner, recognising that the German businessman was backed by an enormous fortune and a fierce determination to find Troy. The two men embarked on a partnership, and Heinrich Schliemann began excavations in 1870, bringing along his much younger second wife, Greek-born Sophia Engastromenou (1852-1932), whom he married in 1869 after divorcing Ekaterina.

Schliemann's excavation methods have been called into question. Employing 80 to 160 unskilled workers daily, Schliemann and his team dug a 14 m (45 ft) trench through the centre of the tell, tossing aside earth and building rubble from layers he considered too late in time to be Troy. Schliemann assumed the lowest layer (Troy 1) was the city of Troy, so destroying the 'real Troy' that was later identified in the upper layers. Pickaxes, shovels, and dynamite were used, and the site was very nearly destroyed, leading many professional scholars to accuse Heinrich Schliemann of being more a treasure hunter than an archaeologist. Kenneth Harl, a classical scholar, said in his Asia Minor lecture series that Schliemann did what the Greeks could not: razed the city walls.

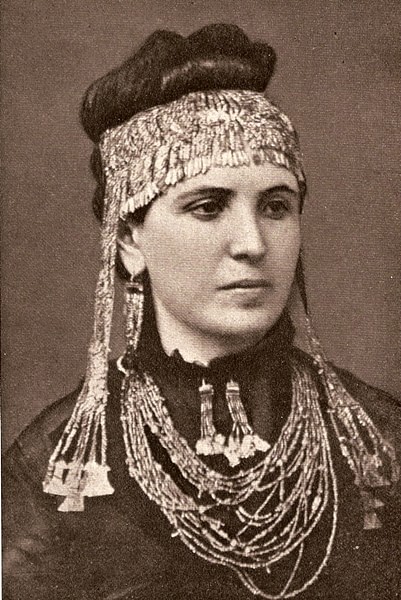

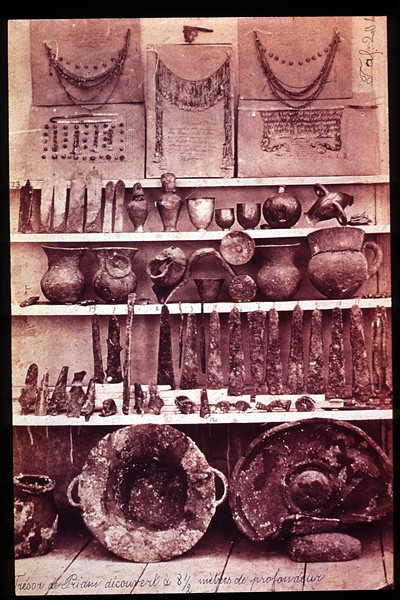

In May 1873, Schliemann claimed to have discovered "Priam's treasure," a hoard of gold, valuable artefacts, and jewellery, including the famed golden diadem (royal headdress) worn by his wife, Sophia, in a photograph taken in 1874. Schliemann equated Priam's Treasure with the riches mentioned in Book 24 of the Iliad. Priam's Treasure was found in Troy II – a layer showing evidence of fire – but Priam would have been the king of Troy during the time of Troy VI (1750-1300 BCE) or Troy VIIa (c. 1300-1180 BCE).

Controversy focused on Schliemann's diaries of the dig, which were incomplete. He also misidentified artefacts, and the dates when some of his discoveries were unearthed are vague. This led to accusations, among them being that Heinrich Schliemann did not tell the truth and combined his findings with artefacts found elsewhere on the site. Schliemann habitually drew any object he found, but Priam's Treasure was photographed instead, and not one of the artefacts was mentioned in early documentation. Did Schliemann's single-minded pursuit of legendary Troy lead him to falsify his discoveries? This is a question that has been asked ever since, and it was not helped by Schliemann later admitting that he had sensationalised the account of his wife, Sophia, being present when Priam's Treasure was found. She was, in fact, in Athens with her family following the death of her father.

Schliemann then smuggled Priam's Treasure (around 8,000 objects) out of Turkey. Most of the collection went to the Neues Museum in Berlin, and during World War II (1939-1945), it was hidden beneath the Berlin Zoo. Soviet soldiers discovered the bounty, and it was taken to Moscow and displayed at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, where the majority of the artefacts are still held. Priam's Treasure has been dated to 2200 BCE or earlier, and this is 1,000 years older than Homeric Troy. Schliemann also crated up pottery, gold jewellery, bronze kettles, and figurines and shipped them to Europe or sold artefacts to private collectors.

In 1876, the Turkish government brought a lawsuit against Schliemann, who promptly left the country and headed to Greece, where he began excavations at Mycenae. Here he discovered the Greek Bronze Age "Mask of Agamemnon," the gold leaf funeral mask of the famous king of ancient Mycenae who led the Greek army in the Trojan War of Homer's Iliad. This find has also met with controversy, with some critics accusing Schliemann of having the mask forged. Modern archaeological research suggests that the separated eyebrows of the mythological king of Mycenae are stylistically different from other death masks found at the site.

Nevertheless, Heinrich Schliemann became an international celebrity, spending over 20 years and seven digging seasons at Troy, deepening and widening what is known as Schliemann's Trench and destroying valuable material in the process. He never credited Frank Calvert, who perhaps may be considered the true discoverer of Homeric Troy.

Although Schliemann's archaeological methods were often brutal, he is considered the founder of modern field archaeology, but it took the work of another archaeologist, one who pioneered stratigraphic excavation, to shift Schliemann's focus from the lower to the upper layers of Troy.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld

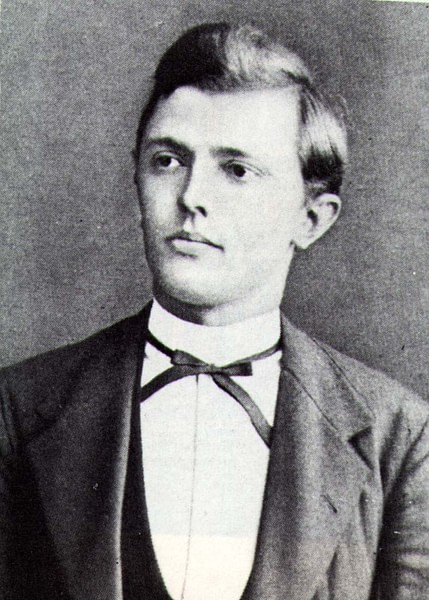

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940) was a German architect born in Prussia, who, like Schliemann, was a firm believer in the historical reality of places mentioned in Homer's epics. His final resting place is in Greece, on the island of Lefkada, overlooking a landscape he argued was Homeric Ithaca.

Dörpfeld studied at the Bauakademie (Academy of Architecture) in Berlin from 1873 to 1876, specialising in ancient Greek architecture. He also studied ancient Greek, and in 1877, was sent to Olympia in the Peloponnese to excavate the Temple of Hera. The young architect developed the "rotting wood" theory while on site, suggesting that the peristyle stone columns in situ were originally wooden. Wilhelm Dörpfeld also developed basic field techniques from observing and meticulously documenting to interpreting and dating historical buildings, a practice called Bauforschung.

Heinrich Schliemann visited Olympia in 1881 and met Wilhelm Dörpfeld, who took him on a tour of the excavations. Schliemann invited Dörpfeld to join him at Troy to assist with the next digging season in 1882. Schliemann had divided the site into nine layers, which he numbered from the lower layer upwards instead of the accepted technique of starting with the upper layers and working down.

Dörpfeld corrected Schliemann's identification of Troy II as being Homeric Troy. Troy II was an extensive early Bronze Age settlement with a fortification wall and evidence of destruction by fire, which prompted Schleimann, in his enthusiasm to find the city, to declare he had found Troy. Dörpfeld considered that it was in the layers of Troy VI or Troy VII where the legendary city lay, and he painstakingly excavated layer by layer.

The German architect was a pioneer of stratigraphic excavation, which meant he systematically identified artefacts in each layer of soil and sediment, thoroughly documented them, and studied the relationship between layers. In Troy VI, Dörpfeld revealed a city with a citadel surrounded by defensive walls, a megaron (large rectangular central hall), pottery, and jewellery, along with evidence of destruction by fire, which were all consistent with Homer's descriptions of King Priam's palace in the Iliad. Dörpfeld argued that Troy VI was the most likely candidate for the legendary city and that Heinrich Schliemann had dug right through it.

In 1890, Heinrich Schliemann collapsed and died on a street in Naples at age 68 as the result of an ear infection, and it was left to his wife, Sophia, to continue financing the Troy dig. Wilhelm Dörpfeld dug for two seasons, in 1893 and 1894, further revealing massive 5-metre-thick (16 ft) defensive stone walls surrounding the citadel with several large towers, public buildings such as workshops and storage rooms, gateways, and mud brick houses – all suggestive of a city with a complex social and economic structure.

Sophia devoted herself to promoting Heinrich Schliemann's work and legacy following her husband's death. She travelled widely, delivering lectures and publishing (with the help of archaeologist Alfred Brueckner) Heinrich Schliemann's Selbstbiographie (autobiography). Sophia Schliemann continued to fund excavations at Mycenae and is credited with the discovery of the tomb of Clytemnestra. Known for her philanthropic work in Greece, she lived out her life in Athens and died at the age of 80. Their son, Agamemnon Schliemann (1878-1954), was the Greek ambassador to the United States in 1914.

In 1887, Wilhelm Dörpfeld was appointed the director of the German Archaeological Institute in Athens, a position he held until 1912. He excavated or studied several sites in Greece: the foundations of the Hekatompedon Parthenon, the Temple of Apollo at Bassae, and the ancient theatre at Epidaurus.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld brought rigor and a more meticulous approach to archaeology, placing a strong emphasis on documenting his findings in detail. He helped to provide a more accurate account of the history of Troy and was – according to the British archaeologist, Sir Arthur John Evans (1851-1941) – Schliemann's greatest discovery.

Carl Blegen

The next major figure involved with Troy's excavations was Carl William Blegen (1887-1971), who was an American archaeologist of Norwegian descent. Blegen was the first professional archaeologist to manage work on the site between 1932 and 1938, leading seven annual expeditions to Troy. Educated at Yale and the University of Minnesota, he was professor of classical archaeology at the University of Cincinnati from 1927-1957, specialising in Greek prehistory.

Blegen was somewhat sympathetic towards Heinrich Schliemann's reckless methods, pointing out that in 1876, scientific excavation techniques were not known. Yet, he differed from Dörpfeld's view that Troy VI showed evidence of fire and destruction from warfare and concluded the city had been destroyed by a violent earthquake around 1300 CE. Working to refine Dörpfeld's stratigraphy, Blegen found compelling evidence to suggest that Troy VIIa (c. 1300-1180 BCE) had witnessed a lengthy siege and was ultimately sacked. His team found Greek-style arrowheads buried in walls, unburied skeletons, animal bones, scorched buildings, and other buildings divided into rooms that could accommodate families seeking shelter. Blegen dated the fall of Troy to c. 1250 BCE.

However, new evidence uncovered by an international team led by German-American archaeologist Manfred Korfmann (1942-2005) of the University of Tübingen suggested that Schliemann, Dörpfeld, and Blegen had merely been digging around the citadel area and a densely populated and far larger lower city existed outside the fortification walls.

The Troy VIIb layer was a demarcation point for Blegen between two very different phases in Troy's history. In that layer, he unearthed pottery showing influences from the southeast Balkans and new architecture such as simpler houses, leading him to consider the distinct possibility that Balkan migrants had replaced the previous inhabitants. This, of course, pointed to the human destruction of the city in the Troy VIIa layer and evidence for the tale of Homeric Troy.

One of Blegen's objectives was to search for cemeteries at Troy, and in 1932, he discovered "A Place of Burning," 90 m (295 ft) northwest of the citadel. This site contained burial urns and amphoras, as well as burnt bones. Blegen interpreted the site as evidence of cremations contemporary with Troy VIIa. Blegen's extensive work, which was continued by the University of Cincinnati's former classics professor Brian Rose in the 1980s, revealed a Late Bronze Age city with a population of 5,000-6,000, covering an area of approximately 35 hectares (86 acres), surrounded by a crenellated fortification wall and defensive U-shaped ditch.

Carl Blegen left Troy to excavate in Greece in 1939, where he found 600 clay tablets inscribed in Linear B script (an early form of Greek), dating from the late 14th-13th centuries BCE. Blegen also discovered the Mycenean Palace of Nestor at Pylos, described in Homer's Iliad.

From Myth to Reality

Despite Heinrich Schliemann's controversial methods, his smuggling of valuable artefacts, and his failure to give credit to Frank Calvert, he uncovered Homer's Troy, proving that the Iliad was based on historical fact. He destroyed the upper layers of Bronze Age Troy and was condemned by later archaeologists for being a flashy treasure hunter, yet his excavations popularised archaeology.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld and Carl Blegen brought scientific rigour and systemic excavation techniques to Troy, meticulously recording the location of every artefact unearthed and studying the context in which it was found. Blegen, in particular, discerned the possibility of a historic Trojan War when he found evidence of human destruction in Troy VIIa.