The Siege of Toulon (29 August to 19 December 1793) was a decisive military operation during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), conducted by a French Republican army to retake the port city of Toulon from rebels, who were supported by allied forces. The siege was a significant milestone in the career of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821).

A Republic in Danger

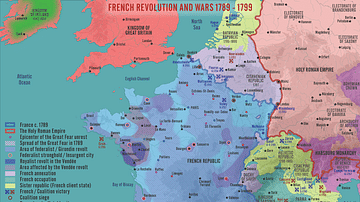

By the summer of 1793, the French Revolution (1789-1799) was moving in increasingly radical directions. The Kingdom of France had been abolished in favor of a French Republic, King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) had been deposed and executed, and the guillotine had become a permanent fixture on the Place de la Revolution in Paris. The fall of the Girondins on 2 June left the destiny of France solely in the hands of the extremist Jacobins, and those who did not share their radical views faced the prospect of being arrested and executed as suspected counter-revolutionaries.

This led to a rapid expansion of the list of France's enemies. Austria and Prussia, who had been at war with France since 1792, were joined the following February by Great Britain, Spain, and the Dutch Republic; these nations coalesced into an alliance later known as the First Coalition, their purpose being the destruction of France's insolent revolution. Internally, the Jacobins' radicalism had caused moderate parts of the country to rebel, as important cities like Lyon, Bordeaux, Marseille, and Toulon cast off their Jacobin administrations and renounced the authority of Paris. These federalist revolts threatened to unravel the infant French Republic from the inside even as the nations of Europe were slowly chipping away at France's frontier defenses. It was no exaggeration when the Republic's legislative body, the National Convention, announced that the patrie (fatherland) was in danger.

The Convention scraped together enough soldiers to put down the rebellions in the south and placed this force under the command of General Jean-François Carteaux, who had been a painter before the war. Carteaux advanced toward the federalist rebels of Marseille, who had seized the nearby city of Avignon. These rebels put up little opposition; Avignon fell to Carteaux on 25 July, and Marseille was recaptured a month later. The victorious Republicans flooded Marseille with Jacobin propaganda and guillotined the main perpetrators of the revolt. After pacifying Marseille, Carteaux prepared to march against Toulon, but before he left, he received dire news: the citizens of Toulon had handed over their city to the Coalition.

Revolt in Toulon

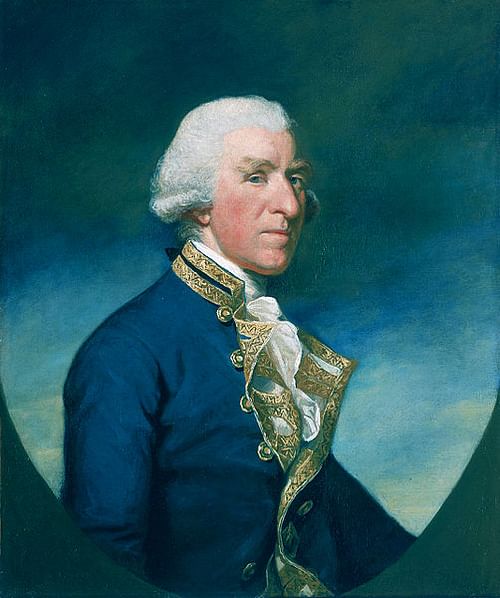

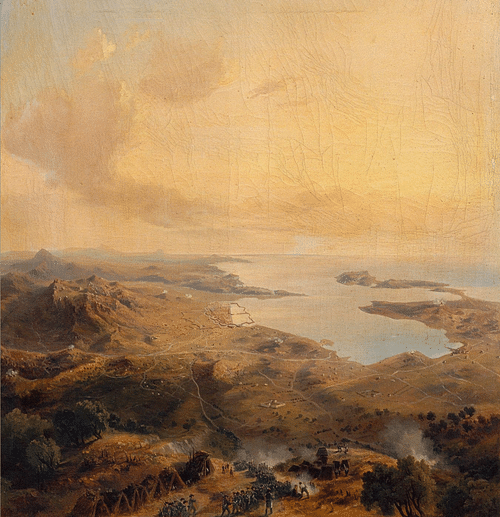

Toulon was a port city on the Mediterranean coast and home to around 28,000 people. It was also a significant naval port, and its harbors contained the entire French Mediterranean Fleet; this included 26 ships-of-the-line and numerous frigates and sloops, amounting to one-third of France's entire naval power. Outraged at the perceived tyranny of the Jacobins, Toulon's moderate republicans rebelled on 12 July, closing their local Jacobin Club and hanging 24 Jacobin administrators. Toulon had a large royalist population, however, and the royalists supplanted the moderates as leaders of the rebellion. When news reached Toulon that a Republican army was descending on Marseille, the Toulon rebels realized they could not withstand an attack on their own. In their desperation, they reached out to the British fleet that had been blockading their port commanded by Admiral Lord Samuel Hood and invited them into the harbor.

Hood was naturally suspicious of the offer and anticipated a trap. On the night of 24 August, he sent Lieutenant Edward Cooke into the city to meet with rebel leaders, deduce their true intentions, and potentially negotiate an alliance. Cooke had to sneak past the docked French fleet whose commander, Admiral Saint-Julien, had remained loyal to the Republic. After landing, Cooke was apprehended by a mob of Jacobin sympathizers but was freed by royalists before he could be harmed. The royalist leaders agreed to hand over both the city and the French ships to the British in return for protection and a promise that all would be returned when the war was over.

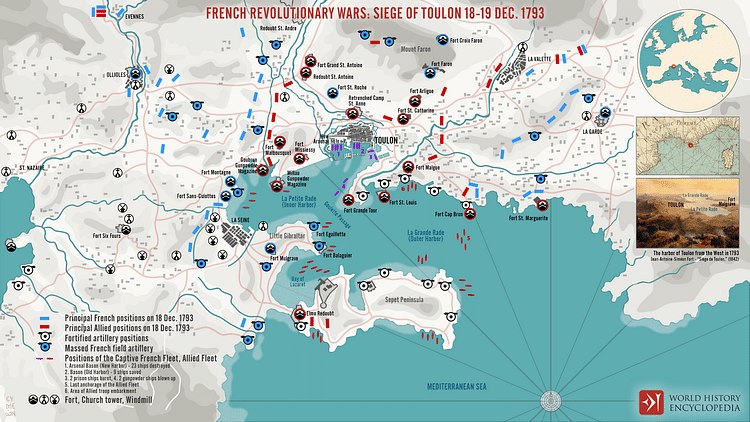

Cooke took these terms back to Lord Hood, who wasted no time in taking advantage of the offer. On 28 August, Hood sent soldiers to occupy the western heights that overlooked the city's harbor, particularly the strategically significant Point l'Eguilette. He then sailed into the harbor aboard his flagship, HMS Victory, accompanied by 19 ships-of-the-line. Saint-Julien and the other Republican sailors had snuck out of the city after realizing the royalists and allies had struck an accord, allowing Hood to capture both Toulon and the French fleet without firing a shot. He was joined by 17 Spanish ships commanded by Admiral Juan de Lángara, as well as Neapolitan and Piedmontese troops. Due to the spontaneity of the enterprise, the allies only had 16,000 soldiers with which to defend the city, and Hood desperately wrote to his allies for reinforcements. He would soon need them, as on 29 August, the French arrived outside Toulon and began to lay siege.

A New Artillery Commander

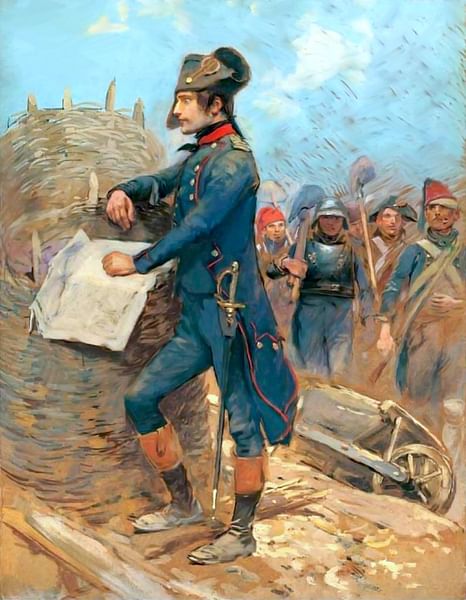

For the French Republic, the recovery of Toulon was top priority. To lose the city and the Mediterranean fleet would mean to surrender all hope of French control of the Mediterranean and would also encourage other parts of the country to rebel. Carteaux was aware of the immense burden placed on his shoulders. He commanded roughly 12,000 troops and was reinforced by an additional 5,000 under General Lapoype, who had been detached from the Army of Italy. This gave the Republicans a slight numerical advantage that would increase as more soldiers filtered in from other fronts. But Carteaux had a big problem: he had no artillery commander. During his push toward Toulon, his chief artillery officer, Captain Dommartin, had been seriously wounded in a skirmish with enemy scouts.

This would have to be quickly remedied, as it was clear the siege would rely heavily on artillery. However, the Republic was rather short on available well-trained officers; many who had not already fled the country had been arrested under suspicion of counter-revolutionary activity. Despite this difficulty, the Republican army would not have to wait long to find a suitable candidate. On 16 September, a young Corsican-born officer, Captain Napoleon Bonaparte, was escorting a convoy of powder wagons from Marseille to Nice. He stopped by Carteaux's headquarters to pay his respects to Antoine Saliceti, a Jacobin deputy of the National Convention who he had known since his days in the Corsican National Guard. Saliceti, who was attached to the army as a representative-on-mission, had been impressed with Bonaparte after the recent publication of his pro-Jacobin pamphlet Le Souper de Beaucaire. When Bonaparte stopped by to say hello, Saliceti gave him command of the Republican artillery on the spot.

Little Gibraltar

Bonaparte's new command was a meager one, consisting only of two 24-pounder cannons, two 6-pounders, a few mortars, and several smaller field guns, as well as an inadequate supply of ammunition. Despite these shortcomings, Bonaparte was determined not to waste this opportunity. He constructed two batteries on a hillside overlooking the western shore of Le Petite Rade, Toulon's inner harbor. On 20 September, these batteries – given the patriotic names of La Montagne and des Sans-Culottes – bombarded the allied ships in the harbor, forcing them to move closer to Toulon, effectively trapping them. Bonaparte noticed that the western heights overlooked Toulon's outer and inner harbors. If he could get a battery up there, he could shell the allied fleet from above. Hood would have no choice but to abandon the city lest he risk damage to his fleet, which would be defenseless beneath the French bombardment. Bonaparte took this plan to General Carteaux, who liked it; all that remained was to chase the allied soldiers from the heights.

Carteaux ordered an assault on 22 September but made the mistake of not sending enough troops. The French were repulsed with "great slaughter", having achieved nothing other than alerting the allies of their intentions (James, 79). Hood responded by sending more men and equipment to reinforce the heights. The allies strengthened their defenses at Point l'Eguilette and Point Balaguier with a formidable new earthwork that was outfitted with 20 heavy cannons and 4 mortars. This system of fortifications was dubbed Fort Mulgrave, nicknamed "Little Gibraltar" by the French. Now, for Bonaparte's plan to succeed, Little Gibraltar must first be taken.

Bonaparte Strengthens the Artillery

Bonaparte was not one for giving up. His next step after the allies constructed Little Gibraltar was to strengthen his own artillery forces so that he would have enough guns to take the fort. Over the next few weeks, he worked tirelessly, writing letters to nearby cities and towns to requisition guns, ammunition, and supplies. He blackmailed the recently rebellious towns around Marseille to give up their horses and sent messages to Lyon, Grenoble, and even to the Army of Italy to demand they send him any unused cannons. He even established an 80-man arsenal at Ollioules to begin making cannonballs. By late October, Bonaparte was in command of 64 officers, 1,500 men, and 100 cannons, howitzers, and mortars.

Bonaparte did all this without consulting his superiors, going over the head of Carteaux by writing directly to the Committee of Public Safety. Bonaparte's disdain for Carteaux, stemming from the bungled assault on the western heights, was shared by Saliceti, who conspired to get Carteaux dismissed in early November. As it turned out, Carteaux's replacement, General François Doppet, was no more competent. On 15 November, Doppet ordered an attack on Fort Mulgrave. The attack went well at first, and the French drove the Spanish troops from the right side of the fort, but Doppet panicked when his aide-de-camp was killed beside him and ordered a premature retreat. Bonaparte was furious, raging that "our blow at Toulon has missed, because a [expletive deleted in the 19th century] has beaten the retreat!" (Roberts, 49).

Doppet was replaced by General Jacques Dugommier on 17 November. Unlike his two predecessors, Dugommier was a veteran and a competent commander who had Bonaparte's respect; Dugommier likewise appreciated Bonaparte's conduct, referring to him as a "rare officer" (Roberts, 51). Dugommier brought with him fresh reinforcements, thereby swelling the attacking French force to 37,000 men. By contrast, Hood's available battle-ready soldiers had dwindled to 12,000; not only had the reinforcements he requested failed to arrive but the soldiers he already had were also being ravaged by disease.

Bonaparte began preparing for the final attack on Fort Mulgrave. Between 15 October and 30 November, he constructed a total of eleven batteries: eight of them were positioned to neutralize Fort Mulgrave itself with crossfire, two more to target Fort Malbousquet on the northern shore of the inner harbor, and the final one to shell the city of Toulon itself. One of these batteries, situated directly below Fort Mulgrave, had a particularly unlucky reputation, especially after the gunners sent to establish it were all killed or wounded. Bonaparte had trouble finding volunteers to man the battery until he named it "Batterie des hommes sans peur" ("Battery of the Men Without Fear"). Afterwards, there was no shortage of volunteers. In another instance, a gunner was killed beside Bonaparte, who immediately took up his blood-soaked ramrod to help finish loading the cannon himself. Such actions helped endear Bonaparte to his men.

Final Push

On 25 November, General Dugommier held a war council, where the decision was made to launch a final attack on Fort Mulgrave so that Bonaparte's plan could finally be implemented. But as the French prepared for their assault, the allies made one of their own; on 30 November, 2,200 allied soldiers launched a surprise sortie from Fort Malbousquet. Led by British General Charles O'Hara, British and Neapolitan troops swept the French from a nearby battery and spiked the cannons. When word reached Dugommier, he wasted no time organizing a counterattack, which he personally led.

The French crept along a trench that was concealed with olive branches until they were within range of the captured battery. Once the French began firing, the allied soldiers panicked and returned fire without aiming, unsure of where the enemy was hiding. After the allies had become sufficiently confused, Bonaparte led the French charge himself, recapturing the battery and sending the allies running back to Fort Malbousquet. General O'Hara, who had been wounded in the arm, was captured. Twelve years earlier, O'Hara had been the man designated to surrender Yorktown to the Americans; now he surrendered to Bonaparte as well, becoming the only officer to have personally surrendered to both George Washington and Napoleon.

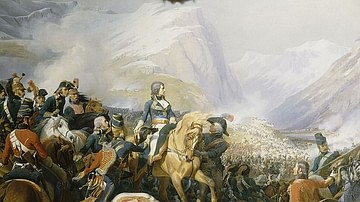

Dugommier decided the time to strike Fort Mulgrave was almost at hand. At 1 a.m. on 17 December, following an intense artillery bombardment, Dugommier ordered the attack. The French advanced amidst icy winds and pouring rain, taking heavy losses from enemy guns. This first column, under Claude Victor-Perrin (a future marshal of the empire) made it past Little Gibraltar's first line of defenses but was stopped at the second line. A second French assault began at 3 a.m., this one led by Bonaparte himself. Bonaparte had a horse killed from under him and received a nasty wound in the thigh from a British bayonet, but his men succeeded in capturing Fort Mulgrave, before carrying on to take the allied defenses at Point l'Eguilette and Point Balaguier.

Despite his wound, Bonaparte oversaw the construction of new batteries on Point l'Eguilette; by the afternoon of the 18th, ten guns were in position and ready to begin shelling the allied ships in the harbor below. Meanwhile, General Lapoype had successfully taken the allied fortifications on Mount Faron and Malbousquet and had positioned additional guns on those heights as well. The capture of these positions signaled the death blow to any hope of an allied victory; the siege of Toulon was over.

Destruction of the French Fleet

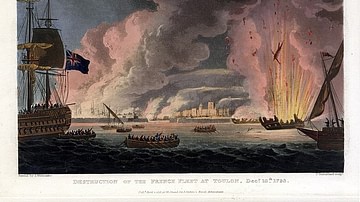

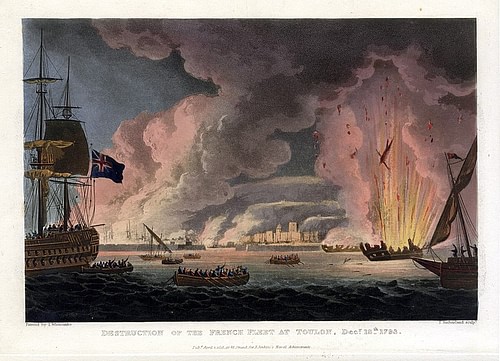

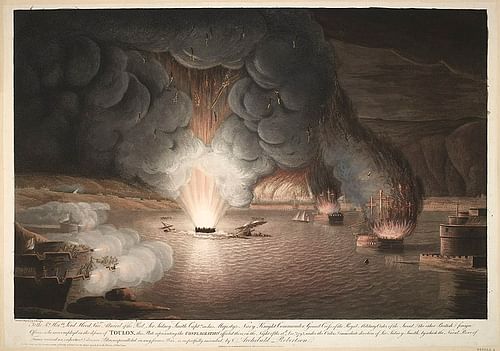

The day that Fort Mulgrave fell, Lord Hood held a war council aboard HMS Victory. It was decided to withdraw from the harbor to avoid risking the valuable ships-of-the-line, and to evacuate as many Toulon citizens as possible. Spanish Admiral Lángara, not wanting to see the French fleet fall back into Republican hands, ordered some of his men to take three boats into the arsenal to destroy as many French ships as possible. Sir William Sydney Smith, a British naval officer who had only recently arrived aboard his vessel Swallow, volunteered to assist. Smith and his team were tasked with destroying the French hulks, which contained the gunpowder stores for the entire fleet and were anchored in the outer roads, as well as entering the arsenal and destroying the ships anchored there.

On the night of 18 December, under the cover of darkness, Smith's team approached the dock gates of the arsenal, which were guarded by 800 freed galley slaves who were sympathetic toward the Republicans. Smith kept his gunboat trained on the galley slaves to ensure they did not interfere as his men went to work. They were spotted by Republican batteries who fired at them, although none of Smith's ships were hit; after Republican soldiers began firing from the shoreline, Smith kept them at bay by firing rounds of grapeshot.

After placing explosives on the anchored ships-of-the-line, Smith ordered the fuses to be lit at 10 p.m., sending parties to set fire to the warehouses on the shore. The light of the blazing inferno gave the French guns a clearer target, and as Smith sailed away, two of his boats were destroyed, and three men were killed. Before returning to the British fleet, Smith made for two disarmed French ships-of-the-line, Thémistocle and Héros, setting fire to them both. Meanwhile, Spanish boats had succeeded in destroying the French powder hulks, resulting in massive explosions. Smith had not destroyed as much of the French fleet as he would have liked, though he did manage to significantly damage it before rejoining Hood's fleet.

Evacuation

While the French were distracted by Smith's attack, Hood ordered three ships to evacuate allied soldiers still left by the waterfront. By the morning of 19 December, these ships had picked up every allied soldier left in the city. The British ships announced that they would be taking as many French royalists with them as possible; 14,877 citizens of Toulon, terrified of the Republic's wrath, packed the decks of these ships. At 9 a.m., as royalists were still being loaded onto the ships, Republican soldiers entered the city, causing a mass panic as citizens rushed toward the shore. Many were killed by the Republican cannonballs falling around them, others were bayoneted by the pursuing soldiers. William James writes that some royalists rushed into the sea and drowned themselves, "preferring instant death to infuriated vengeance" (89).

Indeed, those who did not make it out experienced the Jacobins' vengeance. Under the supervision of Jacobin representatives like Paul Barras, somewhere between 700-800 royalist prisoners were taken to the city's Champ de Mars where they were shot or bayoneted to death without trial. Bonaparte, who was being treated for his wound, did not participate in the massacre, but he was recognized for his instrumental role in the capture of Toulon and was promoted to brigadier general on 22 December, aged only 24. The Siege of Toulon not only saved the French Republic but was an important milestone in Bonaparte's career; shortly after, he achieved fame as the commander of the Army of Italy and was well on the road to becoming Emperor of the French.