Fortifications of one kind or another had been used in Japan since ancient times, but in the period from 1576 until 1639, a new and distinctive style of castle was constructed. Rather than being used for fighting, these were impressive structures intended to enhance the power and prestige of the person that built them. The most famous surviving example of this style of architecture is Himeji Castle in Hyogo Prefecture.

The Warring States Period

The period from the beginning of the Onin War in 1467 until the collapse of the Muromachi bakufu (military government) in 1573 is known as the Sengoku period (Warring States period). As the name suggests, it was a time of civil war. As central authority collapsed, powerful warrior families fought each other for land and power. In Japanese, these are referred to as sengoku daimyo.

As time progressed, the number of sengoku daimyo gradually declined as the more successful ones destroyed the weaker ones. In order for a daimyo to be successful, it was necessary not only to have a good army but also to have a well-organised administrative system that could successfully exploit both the human and natural resources under their control. In the 1560s, Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) emerged as the strongest daimyo in Japan, and in 1573 he entered Heiankyo (Kyoto) and overthrew the bakufu of the Muromachi period.

Oda Nobunaga & Azuchi Castle

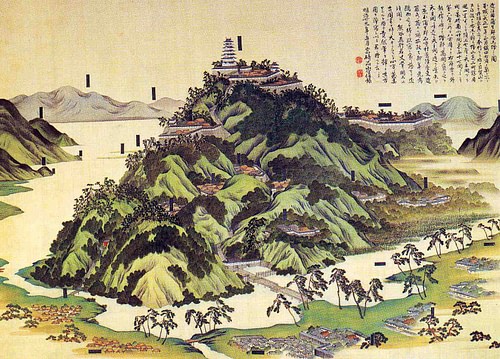

In order to enhance his power and prestige, Nobunaga had a large castle built at Azuchi near the shores of Lake Biwa in central Japan. It took three years to build and was completed in 1579. Azuchi Castle was unlike any fortification that had been built in Japan before. Previous forts had amounted to little more than stonewalls and palisades. These were typically located on remote, strategically advantageous mountaintops and were only occupied in times of war. In contrast, Azuchi Castle was located on the top of a small hill and was intended as a residence.

Azuchi Castle had several features that would later characterise all the castles built in this period. Firstly, it had massive walls five to six meters thick made from huge granite stones fitted carefully together without the use of mortar. The remains of these can still be seen today. Secondly, the main building was much higher than in any previous fortification. In Japanese, the main building in a castle is called a tenshu. This is usually translated into English as "castle keep" or "donjon". However, tenshu were very different to the structures in European castles. At Azuchi, the tenshu was a seven-story building made of wood with the exterior walls being covered in plaster. The uppermost story was octagonal. A series of overhanging eaves and gables sheltered the walls from the rain. There were alternating layers of rounded and pointed gables; cusped windows; pendants hanging from the eaves; and ornamental dolphins mounted on the roof as a charm against fire. The interior contained audience halls, private chambers, offices, and a treasury and was lavishly decorated including paintings by the renowned artist Kano Eitoku (1543-1590). Unfortunately, after Nobunaga was assassinated in 1582, the castle buildings were destroyed, and there has been considerable debate amongst modern historians as to what Azuchi Castle actually looked like.

It has often been argued that this new kind of castle was built because of the introduction of firearms to Japan from Europe in the 16th century. However, this seems not to be the case. The firearms available at the time were simply not effective enough on their own to change the nature of warfare. It seems Nobunaga built Azuchi Castle mainly for political reasons in order to bolster his aspirations to become the ruler of Japan. Although the castle had very extensive fortifications, these were not really for military use. They were intended to show his power. This purpose is also reflected in the positioning of the castle just to the east of Kyoto at a spot where three important roads linking the capital with eastern Japan were located.

Following Nobunaga's death, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), one of his subordinate daimyo, largely completed the reunification of Japan. Hideyoshi also built a number of large castles, including ones in Osaka and Fushimi (Momoyama) near Kyoto. In 1598, Hideyoshi died but, before his death, he appointed a Council of Five Elders to act as regent until his eight-year-old son Hideyori could come of age. Quickly, however, the council members split into two groups. One supported Hideyori, and the others supported a rival daimyo called Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616). In 1600, fighting broke out, and in the Battle of Sekigahara, Ieyasu emerged victorious. In 1603, he had the emperor appoint him as shogun and this allowed him to set up his own government. The period in Japanese history from 1573 to 1600 is called the Azuchi-Momoyama period. It takes its name from the castles that Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi built.

Tokugawa Ieyasu & Edo Castle

The second period in the history of Japanese castle construction began in 1600 with the Battle of Sekigahara and ended in 1615 with the death of Toyotomi Hideyori and the destruction of Osaka Castle.

In 1590, while he was still subordinate to Hideyoshi, Ieyasu had moved his headquarters from central Japan to the Kanto region. There he began the construction of a castle in a small fishing village called Edo (modern-day Tokyo). After he became shogun, he quickly expanded construction and built the largest castle in Japanese history. Edo Castle was not only large but it was also elaborate. The grounds were divided into various citadels surrounded by moats and large stonewalls. On these walls, various towers and watchhouses were built. Each citadel could be reached via wooden bridges with gates on either side. The circumference of the outer perimeter was around 16 kilometres (10 mi). The city of Edo grew up around the castle. After the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868, Edo Castle became the home of the imperial family and was renamed the Imperial Palace. The grounds of the present-day Imperial Palace are only about one-third the size of the original castle grounds. Its moats and stonewalls, however, are a reminder of how large Edo Castle must have been.

In addition to Edo Castle, Ieyasu also built a number of other castles, such as Nagoya Castle and Nijojo Castle in Kyoto. In this period, other daimyo also built castles. These included Kato Kiyomasa (1562-1611) who built Kumamoto Castle, Ikeda Terumasu (1565-1613) who built Himeji Castle and Mori Terumoto (1553-1625) who built Hagi Castle. Towns developed around castles, and 'castle towns' (jokamachi) became one of the distinctive features of urban development in the Edo period.

In the 1610s, Tokugawa Ieyasu had taken various steps to consolidate his control of the country. He felt, however, that Toyotomi Hideyori's continued survival posed a threat. In 1614, he decided to launch an attack on Osaka Castle with a view to killing him. The initial campaign was indecisive, but in the negotiations that followed, Hideyori agreed to the outer moat of the castle being filled in and part of the walls being dismantled in exchange for the siege being lifted and a promise of peace. In the following year, however, Ieyasu reneged on his agreement and renewed his attack. He destroyed the castle and finally wiped out the Toyotomi clan. This was the only occasion in which one of these large castles actually came under attack.

The End of Castle Construction

The last period of castle construction lasted from 1615 until 1638. Immediately after the destruction of Osaka Castle, Ieyasu implemented a number of policies aimed at strengthening the Tokugawa control of the country. Some of these had a direct impact on castle construction. Henceforward, daimyo were only allowed to have one castle in their territory and any others had to be dismantled. Existing castles could only be repaired with Tokugawa approval, and there was a ban on building new ones. This meant that in this period, the only castle construction that took place were projects conducted by the Tokugawa clan themselves. These included rebuilding Osaka Castle and the continued development of Edo Castle, which was finally completed in 1638.

The Decline of Castles

With the coming of peace and the ban on new construction, castles went into decline. During the Edo period, many daimyo experienced financial difficulty, and castles were costly to maintain and served little useful function. Over time, earthquakes, erosion, lightning strikes, typhoons, and fires destroyed dozens of tenshu and hundreds of gates and watchtowers. In 1657, for example, fire destroyed the tenshu of Edo Castle. In 1660, lightning ignited the gunpowder warehouse at Osaka Castle and the castle caught on fire. In 1665, lightning struck and burnt down the tenshu. The same thing happened at Nijojo Castle in 1750, and in 1788 a citywide fire destroyed many other buildings there. When castles were damaged in this way, mostly they were not rebuilt.

In the 1860s, a movement to overthrow the Tokugawa and re-establish direct imperial rule developed. This led to actual fighting in the Boshin War, but castles played only a minor role. As with Edo Castle, defenders mostly surrendered without a fight or after a brief resistance. The few regions where castles were seriously defended were generally far from the main conflict and only had to hold out against limited attacking forces. Despite this, some castles were destroyed in the fighting. For example, the tenshu of Osaka Castle was burnt down after it had been surrendered.

Castles After the Meiji Restoration

After the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa political system was abolished. Daimyo lost their positions, and ownership of many castles was handed over to the new central government. As castles no longer served any function, they came to be seen as a symbol of a bygone age, and many were demolished or simply abandoned. In 1872, the government undertook a survey to find out which were worth keeping and which could be done away with. The new Army Ministry took possession of quite a few castles in the belief that they could be used for military purposes in the future. Some regimental headquarters came to be located on castle grounds. This connection with castles was used for propaganda purposes because it helped promote the idea that the modern Japanese army had directly inherited the country's warrior traditions when this was not actually the case.

With the passage of time, people who had been born before the Meiji Restoration gradually died out, and the Edo period came to be seen as a historical period with little contemporary political significance. As this happened, castles came to be viewed as an important element in Japan's cultural heritage. Historians began to do research about them, and there was a movement to preserve the castles that remained. Reflecting this new spirit, in 1931, the tenshu of Osaka Castle was reconstructed in concrete.

The tenshu at both Hiroshima and Nagoya Castles were destroyed during World War II (1939-1945). As the Japanese economy recovered in the post-war period, however, there was a move to rebuild more tenshu. Also, castles, especially those that had original buildings, became sources of local pride and popular tourist attractions. For foreign tourists, no trip to Japan is complete without a visit to see a castle. The easiest ones to access are those in the large cities, but the tenshu in both Nagoya and Osaka castles are reconstructions. There are twelve castles with original tenshu. These are:

- Maruoka (1576, Fukui Prefecture)

- Matsumoto (1596, Nagano Prefecture)

- Inuyama (1601, 1620, Aichi Prefecture)

- Hikone (1606, Shiga Prefecture)

- Himeji (1609, Hyogo Prefecture)

- Matsue (1611, Shimane Prefecture)

- Marugame (1660, Kagawa Prefecture)

- Uwakima (1665, Ehime Prefecture)

- Bitchu-Matsuyama (1684, Ehime Prefecture)

- Kochi (1747, Kochi Prefecture)

- Hirosaki (1810, Aomori Prefecture)

- Matsuyama (1854, Ehime Prefecture)

Of these, Himeji and Matsumoto are generally regarded as being the most impressive.