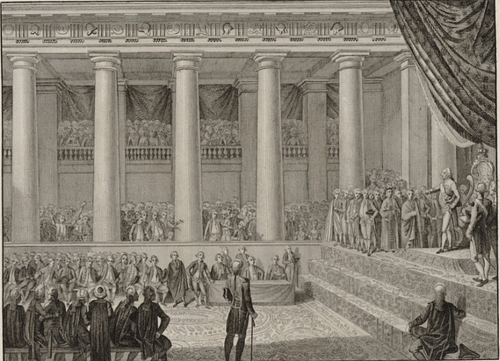

On 20 April 1792, King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) stood before the Legislative Assembly and, with a faltering voice, read a declaration of war against Austria, to the ecstatic delight of the gathered deputies. This declaration sealed his own fate, the fates of the Girondins who pushed for it, and catapulted Europe into 23 years of perpetual, bloody warfare.

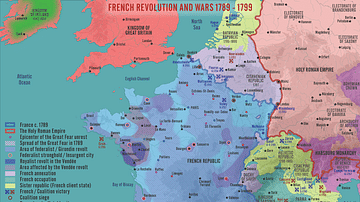

The French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) and the successive Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) ended with a Bourbon Restoration and the reversal of much of the progress made during the French Revolution (1789-99). Some historians have viewed the outbreak of the Revolutionary Wars as nothing more than a power grab by the Girondins and a secret ploy by Louis XVI to regain power. However, many in the Legislative Assembly and, indeed, many in France believed that a war was necessary to unmask the Revolution's enemies, destroy the threat of the émigrés, and bring liberty to all the oppressed peoples of Europe. Ignoring Robespierre's warning that no one loves armed missionaries, the French instead embraced the concept of a 'universal crusade', viewing war as the logical next step in their Revolution.

A Clean Slate

On 30 September 1791, the National Constituent Assembly met for the last time. After two long years, it had fulfilled its purpose and had given France a new constitution which supposedly reconciled the king with the revolutionary reforms, officially transforming the country into a constitutional monarchy. For many, this should have been the final day of the Revolution, the restoration of stability to a country of newly liberated citizens, but the Revolution was more divided than ever before. Scarred by Louis XVI's abortive escape attempt from France last June, known as the Flight to Varennes, many questioned whether Louis could be trusted at all, with some extremists calling for his abdication and the creation of a republic. Citizens were also put on edge by the Declaration of Pillnitz, a joint statement by the monarchs of Austria and Prussia that seemed to threaten France with invasion and reverse the gains of the Revolution.

The divisions manifested themselves in two opposing factions. The Feuillant Club was the Assembly's conservative faction, advocating for a stable constitutional monarchy and an end to the Revolution. Having arisen in response to calls for a republic, the Feuillants had scored a major victory by successfully pushing the constitution through the Assembly and restoring some of the king's authority. Opposing them was the Jacobin Club, the increasingly radical group that believed the king had betrayed France and should be punished. While not yet a republican faction, some Jacobins associated with extremist parties such as the Cordeliers. Once the dominant political force in the Revolution, the Jacobins had lost ground to the Feuillants, who exerted the most influence in the Constituent Assembly in its final months.

When the Constituent Assembly's succeeding body, the Legislative Assembly, met in Paris on 1 October, it represented a politically clean slate. Due to a self-denying ordinance proposed by Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794), none of the members of the Constituent Assembly was eligible to stand for election to the Legislative; therefore, the 745 Legislative deputies were a much different sample of the population. While the Constituent had been comprised of men with varying backgrounds and pedigrees, the Legislative was almost entirely bourgeois, with a few notable exceptions such as Marquis de Condorcet. On average, the new legislators were also spectacularly young, with a good portion of them under the age of 30. Additionally, they were mostly politically inexperienced.

Immediately, these new deputies were courted by the powerful political clubs. By November, half of the deputies had chosen a side; 334 had gone to the Feuillants, while only 136 had signed up with the Jacobins. When the Assembly met, the Feuillants sat together on the right side of the hall, while the Jacobins clumped together on the left. This seating arrangement gave rise to the political terms 'right' and 'left' which are still used today. The roughly 300 undecided deputies sat in the center, earning them the nickname 'the Plain' or, more derisively, 'the Swamp'. At first, the Plain tended to support existing constitutional arrangements, and voted in step with the Feuillants. However, as time went on and tensions rose, the Plain found their attentions were being diverted by some extraordinarily persuasive voices on the political (and literal) left.

Rise of the Girondins

These gifted orators were soon to be known as Brissotins, after their leader Jacques-Pierre Brissot (1754-1793), although they would later be more commonly referred to as Girondins, since many of them hailed from the Gironde department of France. The Girondins were not a political party in the modern sense of the term, but rather a close-knit group of friends who often dined together and spoke on the same issues on the Assembly floor.

They made use of their numbers by brilliantly playing off one another, so that their impassioned speeches resembled "a string quartet" in the words of historian Simon Schama (584). Unlike Robespierre, the austere lone wolf of the Jacobins, the Girondins recognized the power of their cohesiveness and knew how to use it to put on a performance. Both Schama and historian T. C. W. Blanning mention how electrifying their speeches were, even when read from the dusty, yellowed pages of the Archives Parlementaires (Schama, 584; Blanning, 60).

Aside from Brissot, a journalist from Chartres, the Girondins consisted of Pierre Vergniaud, a 34-year-old lawyer from Bordeaux; Jean-François Ducos, a 26-year-old merchant; and Marguerite-Elie Guadet, a 33-year-old barrister who would become one of Robespierre's most formidable opponents, among others. The Girondins had republican sympathies; Brissot had been one of the authors of the petition to replace the king that had been the cause of the Champ de Mars Massacre. They wished to curtail the influence of the Feuillants and limit Louis XVI's power. In order for this to be accomplished, the Revolution not only had to continue but expand in scale.

In his first major speech on 20 October, Brissot denounced the émigrés, namely the clergymen, aristocrats, and military officers who had fled France in droves during the Revolution and threateningly settled just beyond the border in cities like Trier, Mainz, and Koblenz. He blamed the émigrés for the recent depreciation of the assignat (ignoring the true culprit, inflation), alleging that their presence had made speculators lose confidence in the currency. Moreover, the Declaration of Pillnitz showed the hostility of the émigrés who appeared to be working in concert with the devious Austrians. With great efficiency, Brissot and his allies convinced the Assembly to act against the émigrés.

On 31 October, it decreed that all émigrés who had not returned to France by 1 January 1792 would be guilty of conspiracy and sentenced to death. On 29 November, the Assembly announced the confiscation of all émigré property, including that owned by family members who had remained in France. The same day, the Girondins also passed legislation attacking refractory priests: Catholic clergymen who had not sworn oaths of loyalty to the state as required by the 1790 Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Refractory priests would henceforth also be considered guilty of conspiracy.

King Louis XVI used his royal veto on these draconian measures, but the growing influence of the Girondins could not be denied. Hostility to the émigrés resulted in calls for war against the Prince-Bishop of Trier, who was hosting them. Louis XVI's Feuillant advisors begged him to follow an anti-war policy, but surprising everyone, the king sided with the Girondins, who were now being referred to as the war party. On 7 December, he appointed the Comte de Narbonne-Lara as his minister of war, who immediately began to plan for war with the Electorate of Trier.

Clamor for War

Louis XVI had very different motivations for wanting war than the Girondins. Since the start of the Revolution, he had been made a virtual prisoner by his own people and had watched as his powers were gradually stripped out from beneath him. In his mind, he had nothing to lose and everything to gain from a conflict. If the war went well, he could use his status as commander-in-chief of the military, guaranteed to him by the constitution, to claim credit for the victory, and could use that popularity to regain some authority. If it went poorly, the foreign armies would likely dismantle the revolutionary government and restore him to his full powers. His wife, Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), hoped for the second option and began secretly sending French military secrets to her contacts in Austria. "I do believe we are about to declare war on the Electors [of Mainz and Trier]," she wrote to her friend and former lover, Count Axel von Fersen. "The imbeciles! They cannot see that it will serve us well." (Schama, 587)

Another unlikely supporter of war was none other than Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), who had retired to his estates in Auvergne after his fall from grace the previous summer. Lafayette saw a limited war with Trier as a perfect opportunity to regain his lost popularity and began lobbying the Comte de Narbonne for command of the army. Still an influential Feuillant voice, Lafayette's support convinced many on the right that war might be the best option, and even more deputies rallied behind the Brissotin call to arms.

On 14 December, the king appeared before the Assembly, announcing that he had issued an ultimatum to the Prince-Bishop of Trier: put a stop to all émigré activity within his lands, or prepare for war. Aside from some of the Feuillants, the Assembly uproariously applauded the king for minutes on end. Meanwhile, Narbonne began mobilizing three armies, totaling 150,000 men. As France braced for war, news reached Paris that the electors of Trier and Mainz had adhered to the king's ultimatum, and had exiled all émigrés from their territories. Although the casus belli was removed, France was no less desirous for war, and now turned to the one foe who many believed had been the true enemy all along: Austria.

Universal Crusaders

France's rivalry with the Habsburg monarchy was deeply rooted, stretching back to at least the period of the Thirty Years' War. Several conflicts in the early 1700s had intensified this hatred, a loathing second only to France's great tradition of Anglophobia. So it was quite shocking when, in 1756, King Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774) entered into a formal alliance with Austria, which would be sealed 14 years later when the Austrian archduchess Marie Antoinette was wed to Louis XVI, then dauphin.

For many French citizens, the alliance of 1756 was nothing short of catastrophic and was the primary cause of France's diminishment on the world stage. As many saw it, the alliance had forced France to sit meekly by as the Austrians pursued their interests, which were often in conflict with France's. By 1791, the alliance was still technically in effect, although Girondin politicians railed against it; Pierre Vergniaud claimed that the destruction of the 1756 alliance was as vital to the recovery of French liberty as the Storming of the Bastille had been.

It was not a difficult task to present the Austrians as boogeymen, as many French citizens had been fearing an Austrian invasion since the earliest days of the Revolution. Habsburg emperor Leopold II (r. 1790-1792) was Marie Antoinette's brother and had openly declared himself in opposition to the Revolution with the Declaration of Pillnitz. Additionally, he was seen to be harboring émigrés. As far as the French knew, he could strike at any moment. It was critical, argued the Girondins, that France strike first. It was not only a matter of defending France but also of extending the Revolution, of carrying its principles to all the peoples of Europe on the point of a bayonet. Brissot termed this a 'universal crusade', playing on his countrymen's passions for liberty that had been stirred up by the French Revolution and by the American Revolution before it.

For the Girondins, the armies of Europe were comprised of slaves, men oppressed by despots and forced to fight the wars of kings. Naturally, they would throw down their weapons at the sight of the French citizen armies, who had come to liberate them. Why should revolutionary progress be limited to France, when the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen had proclaimed natural rights for all men? "If the Revolution has already marked 1789 as the first year of French liberty," said Elie Guadet, "the date of 1 January 1792 will mark this year as the first of universal liberty" (Schama, 594). Guadet's speech was followed by Vergniaud, who urged French citizens to

Follow the course of your great destiny that beckons you on to the punishment of tyrants…Glory awaits you. Hitherto kings have aspired to the title of Roman citizens; it now depends on you to make them envy that of Citizens of France! (Schama, 595).

While it is true that the Girondins wished to gain power for themselves, they likely believed their own impassioned propaganda and thought that Europe longed to be free just as much as they did. Such rousing, patriotic rhetoric did not appeal to everyone. Amidst the clamor for war and glory, Robespierre stood alone, warning that war would bring only harm and destruction to France. Rather prophetically, he cautioned that a war would either return power to the royal court or result in a military dictatorship. Robespierre knew that all talk of enslaved soldiers welcoming the Revolution with open arms was wishful thinking, famously stating, "No one loves armed missionaries" (Schama, 595). Robespierre's opposition was the first sign of the bloody rift that would develop between the Robespierrist Jacobins and the Brissotist Girondins.

The Road to War

In January 1792, France declared that by plotting with Europe's monarchs to overthrow the Revolution, Austrian Emperor Leopold II had invalidated the 1756 alliance. Louis XVI declared that his brother-in-law was to renounce all treaties hostile to France and publicly declare his peaceful intentions by 1 March. Failing this, war would ensue. The Austrians were undeterred by this threat, as they had recently entered a defensive alliance with Prussia. Prince Kaunitz, Austria's 81-year-old chancellor, replied by warning that if any French army crossed into Germany for any reason, retribution would swiftly follow from "the other sovereigns who have united in a concert for the maintenance of public order and for the security and honor of monarchs" (Blanning, 61).

Having falsely believed the Declaration of Pillnitz had been a successful deterrent, Kaunitz thought that a follow-up threat would be sufficient to make the French back down. His response unwittingly played into the hands of the Girondins; if it had not appeared to have been a struggle between liberated and oppressed peoples before, Kaunitz's letter was all the proof the Girondins needed. The call for war intensified, as Assembly deputies swore oaths to live free or die, a veritable reenactment of the Tennis Court Oath of 1789.

On 1 March, the deadline of the French ultimatum, Leopold II unexpectedly died and was succeeded by his 24-year-old son, Francis II. No one could guess the intentions of this new emperor, but the fervor in the Assembly continued to grow. On 10 March, Louis XVI dismissed his entire ministry and replaced them with allies of Brissot, much to the Feuillants' shock.

His new minister of foreign affairs was Charles François Dumouriez (1739-1823), a career soldier and committed Austrophobe. Dumouriez appeared at the Jacobins sporting a red cap of liberty and championing the cause for war, a popular show despite Robespierre's condemnation. In April, Dumouriez tried and failed to secure Prussian support, appealing to the memory of King Frederick II the Great (r. 1740-1786), who was widely viewed as an enlightened ruler.

Meanwhile, Francis II showed what kind of ruler he would be when he ordered the mobilization of Austrian troops on the French border in mid-April. The time had come to act. On 20 April 1792, Dumouriez gave an official report on the situation. He and the Girondins claimed that the House of Habsburg had made France a slave to its ambitions since 1756, and urged an immediate declaration of war. After the enraptured applause, a vote was held; all but seven deputies voted in favor of war. Later that day, Louis XVI read out the declaration of war against the king of Hungary and Bohemia, Francis II, who had not yet officially been elected Holy Roman Emperor. For better or worse, the French Revolutionary Wars had begun.

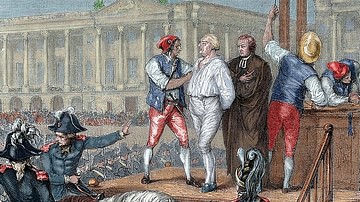

The war would have significant consequences for the Revolution. Early defeats would lead to mass hysteria and bloody incidents like the Storming of the Tuileries Palace, which marked the end of French monarchy. The victory at Valmy on 20 September would be the catalyst for the establishment of the Republic, and the eventual execution of the king.

Despite enjoying the height of their influence in 1792, Brissot and his Girondist friends would be some of the first victims of the Reign of Terror, executed in October 1793. As for the war, it turned out Robespierre was right; no one loved armed missionaries. The conflict would survive the Revolution and many of the revolutionaries themselves, blossoming into a worldwide conflict that would shake Europe to its core, and end 23 years later, at the Battle of Waterloo.