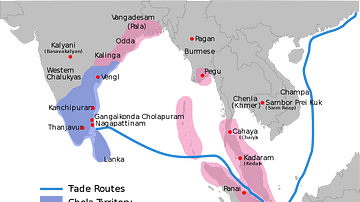

Like many great civilisations, the origins of the Chola, a Tamil Hindu dynasty in southern India, are shrouded in the temporal mists of uncertainty and obscurity. It is however known that they were influential from at least the 3rd century CE, emerging as a vassal state of the Pallava dynasty in the 9th century, holding sway over Tanjavur (in the modern state of Tamil Nadu) with respectful allegiance to Pallava supremacy. Around the middle of the 9th century, the situation changed, and the Cholas began to assert their authority, claiming Tanjavur, which became the capital city for the duration of their subsequent political dominance in the region. Under Aditya Chola (r. 871–907), a talented diplomat and general, the Chola Empire was effectively founded, and the Cholas swiftly established themselves as a dominant power in the area of Tanjavur and the Kaveri river. Further conquests followed in Tondai Nadu (Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu) taking territory from the Pallava and Pandaya kingdoms, as well as the Ganga dynasty to the north in a strategic alliance with the Chera dynasty who occupied parts of the adjoining areas (Kerala and Tamil Nadu).

In the early reign of Parantaka (907–955), the Chola domain extended to Chennai (Madras) on the east coast, and to Kalahasti (southern Andhra Pradesh), and the Pallava and Pandaya kingdoms were also subjugated during this time. With the establishment of the Chola-Mandalam (anglicised in the modern era as Coromandel), Chola territory extended along the eastern seaboard (from northern Andhra Pradesh to northern Tamil Nadu).

Chola Temples

Prior to Chola supremacy, the Pallavas had built a number of impressive temples, notably the rock-cut cave temples and sanctuaries at Mahabalipuram on the Coromandel Coast in the 6th century, and magnificent temples were built at Kanchipuram in north-eastern Tamil Nadu by Rajasimha I (r. 700–728) and his successors. To establish Chola dynastic legitimacy, the Chola kings sought to emulate and surpass these architectural achievements through a monumental building programme of granite temples, notably under Rajaraja Chola (r. 985–1014) under whose patronage the massive Brihadisvara temple at Tanjavur was built; and his son Rajendra Chola I (r. 1012–1044) who constructed the monumental Brihadisvara temple at Gangaikondacholisvaram in his new capital city (for a brief period) further to the north; and the smaller but nonetheless splendid temple of Airavatesvara at Darusaram built by Rajendra Chola II (r. 1143–1173). All three temples, dedicated to Shiva, whose impressive remains dominate the modern landscape, designated as the Great Living Chola Temples by UNESCO, were inscribed on the World List in 1987.

Shiva (‘Auspicious One’) the third of the triumvirate of Hindu gods (along with Vishnu, the principal Hindu god, and the goddess Devi), is a complex, multi-faceted deity, both a creator and destroyer, and thus dangerous as well as auspicious. Shiva’s extraordinary temples of course demanded representations of the god – both fixed and portable – to suit the necessary requirements of ritual, many produced in bronze, and their sensuous beauty represents the greatest artistic legacy of the Chola culture. These depict the god in several manifestations: as Nataraja (Lord of the Dance), Tripuravijaya (Victor of the Three Cities), Chandrashekhara (Lord Crowned with the Moon), Shrikantha (Lord of the Auspicious Neck), Vinadhara (Player of the Vina), Somaskanda (with Uma and Skanda), and others; forms that are examined in more of their beautiful detail after a necessary excursion in more depth to the architectural wonders that were briefly described above.

Tanjavur

Synonymous with the greatest architectural achievement of the Cholas, the Brihadisvara temple at Tanjavur is known from inscriptions as Dakshina Meru, inaugurated by Rajendra Chola I probably in 1003–1004. The huge edifice, square in plan, is encompassed by a massive colonnaded perimeter wall (prakara) with shrines dedicated to the deities of direction (ashatadikpalas) and a main entrance with a tower (gopura), an entrance porch, two adjoining prayer halls (mandapas), vestibule (antarala), and inner sanctum (garbhagriha) with many sculptures of Shiva and other personalities; the main temple tower (vimana) reaches the lofty height of 59.82m above ground level.

Gangaikondacholisvaram

At Gangaikondacholisvaram, the Brihadisvara temple built by Rajendra Chola I was completed in 1035, and is similar in design to the great temple built by his father at Tanjavur. Its main tower, at 53m in height, although lower than its predecessor, features recessed corners and a graceful upward curving form, contrasting with the straight and rather severe tower at Tanjavur. The inner sanctum is accessed through a beautiful pillared hall (subsequently rebuilt). Its three entrances are guarded by pairs of monumental guardian deities (dwarapalas), and the complex features many elaborate stone sculptures depicting Shiva in his various manifestations and other prominent figures, as at Tanjavur.

Darasuram

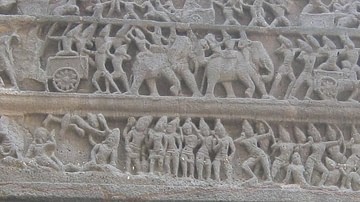

At Darasuram, the third of the great royal Chola temples dedicated to Shiva, the Airavatesvara, was completed by Rajendra Chola II in 1167, whose capital was at nearby Palaiyarai. Also square in plan, it is considerably smaller in scale compared to the Brihadisvara temples at Tanjavur and Gangaikondacholisvaram, and also differs from them in its highly ornate style, although the inner sanctum is not encircled by a circumambulatory path, unlike its predecessors. This contains a shiva-linga, an aniconic representation of the god. Its main tower is considerably lower than the two earlier temples at 24 m in height. The front pillared hall, the agra mandapa, is intriguing in that it is conceptualised as a horse-drawn chariot, a trait inspired by Pallava architecture; its columns are ornamented with representations of stories from the epics and Puranas, such as the burning of Manmatha, Parvati performing penance, Shiva’s marriage, the birth of Skanda/Kumara, Shiva’s fights with the asuras, and other narrative scenes. The base of the outer pillars of the agra mandapa represent gaja-yalis with curled trunks and tails, and this part of the temple has a great number of other representations. The base of the main temple is notable for its stone frieze of panels containing inscriptions of the stories associated with the 63 nayanmars (Shiva saints), and a number of these also depict women in yoga postures, and other scenes from everyday life. This temple also features a separate impressive Amman shrine, the Periya Nayaki, dedicated to Devi. The perimeter wall has pillared cloisters on the inside with cells in between for deities. Carved on a balustrade of a staircase leading to the pillared cloisters is the celebrated ‘Rishaba Kunjaram’, a stone sculpture featuring a conjoined bull and elephant.

Chola Sculptures

Many of the splendid sculptures that survive were cast in bronze and more modest in scale by comparison with the larger sculptures that were venerated in temples, designed instead to be portable, to enable the deity to be paraded away from the temple sanctuary both for the god’s pleasure and the spiritual benefit of worshippers. This practice still continues in the modern era, where the god is designed to be seen (darshan), and small-scale metal sculptures (utsavamurti) are empowered through rites to act on behalf of the immobile sculptures within temples. For this reason, many bronzes appear worn in their finer details, such as the eyes, as a result of bathing and anointing over centuries of worship, and are sometimes recut for aesthetic reasons. Chola bronzes were made using the lost-wax casting technique that is still practised today in India and elsewhere. This highly skilled process involves the modelling of the figure in wax resin which is then covered with layers of clay. The clay mould is heated, permitting the wax to melt and drain, the hollow space is then filled with molten bronze, and when cooled the clay casing is broken away. Figures are either cast solid – ‘direct-cast’ – or modelled over a clay core and ‘hollow-cast’.

Shiva Nataraja

Chola bronzes strike a special chord with the Western eye where Indian culture is concerned. Shiva Nataraja – Lord of Dance, is particularly evocative of this perception, appearing as divine yet elegant, exotic, fantastical, fluid, sensual, and spiritual – in essence an abstract rather than realistic artistic form. This is epitomised by a stunning bronze in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Shiva is poised dramatically on his right leg bent nearly at a right angle and resting on the small demonic figure of Mushalagan, his left leg raised gracefully above, holding fire in his left rear hand (symbolising destruction), a damaru drum in his rear right hand (its beat denotes creation), near a rearing cobra, his right front hand gesturing protection (abhaya), as does the left front hand. Nataraja stands supreme within a flaming aureole (prabha) representing the oscillating universe, his matted locks dramatically splayed out by his rhythmic dance, known as the ananda tandava. This is described in a poem:

When he playfully began his dance there proceeded from his twisted locks of hair as they beat against each other with increasing speed the water of the heavenly river breaking into spray.

(Kuncitanghristava, verse 111)

This figure defines the mastery of Chola bronzes – quintessentially oriental and its defining attributes – arguably the finest accomplishment of medieval metal sculpture in existence, admired by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin as the perfect example of rhythmic movement, and synonymous with Chola art. In 1913, praising the Shiva Nataraja from Tiruvalangadu, Rodin wrote: "Above all, there are things that other people do not see: unknown depths, the wellsprings of life. There is grace in elegance; above grace, there is modelling." (Rodin, 1921).

Shiva Tripuraavijaya

Shiva Tripuravijaya – Victor of the Three Cities, represents an especially potent form without detracting from the artistic sensitivities that characterise Chola bronzes as defined above, exemplified by a fine bronze in the National Museum, New Delhi (below). This majestic image of the god is one of the greatest embodiments of his regal form, conceived to express the majesty of kingship, this type was naturally revered by Chola rulers as both their spiritual protector and role model of imperial conquest. Shiva’s hands are poised to hold a bow and arrow (which are now missing), to destroy the cities of three demons. He stands serenely counterpoised (contrapposto) with a towering crown of matted hair. According to the tradition of a hymn by Sundarar, thought to have flourished in the early 9th century:

In a flash, taking the mountain as your bow, with a single arrow shot with a roar from the bowstring, you burnt the Three Cities with their banners to a charred ruin.

(Sundarar, Hymn 7, 9.4)

Shiva Chandrashekhara

Shiva Chandrashekhara – Lord Crowned with the Moon, appears rather more benevolent than some guises of Shiva, represented by a stunning figure in the Brooklyn Museum. In this case, the splendid bronze figure holds an antelope in his left rear arm and a battleaxe in his right rear arm, which emphasise his role as a protector, especially of the animal kingdom; the god’s front right hand is raised in the abhaya gesture of protection, while the front left hand holds the stem of a flower which is now lost; the crescent once adorning his crown of matted hair is not preserved. Shiva stands straight and still although his animated hand gestures suggest that he is ready to strike. Sandara says of Chandrashekhar:

That crescent moon brushing the top of the palaces with their great cool walls, circled by flowering groves, crowns your matted hair, lord of the great Ancient Hill.

(Sundarar, Hymn 7, 25.7)

Shiva Shrikantha

Shiva Shrikantha – Lord of the Auspicious Neck, also known as Nilakantha (Blue-Throated One), or Vishapaharana (One Who Captured the Poison), is essentialised by a fine bronze in the British Museum. These titles refer to the role of Shiva as imbiber of poison at the time of the universal deluge in Hindu mythology when the cosmic waters submerged the planet. Shiva is represented in this guise as tranquil, serene, noble, and richly adorned, with a matted towering crown of hair, depicted as the saviour of the world. He sits in the lalitsana, the position of repose, left leg crossed, right leg resting on a lotus, his front right hand raised in the abhaya gesture, in the rear right hand he holds a battleaxe, front left hand a cobra, rear left hand an antelope. According to a hymn of Sandara:

When the gods churned the ocean with the biting serpent and the mountain, and the kalakuta poison arose, you knew it would destroy the worlds: so you swallowed it as your elixir and haven’t yet spat it out.

(Sundarar, Hymn 7, 9.19)

Shiva Vinadhara

Vinadhara – Player of the Vina, portrays Shiva in an elegant poise as master of music, represented in a fine bronze in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Surmounted by the characteristic matted crown of hair Shiva stands in a relaxed pose, his two front hands hold the lute-like vina, while his left and right rear hands hold an antelope and battleaxe. This type is remarkably similar to representations of Shiva Tripuravijaya who carries a bow and arrow. Music was considered to be an essential component of sacred learning, its rhythms embody the structures of the creation of the universe and its ongoing process, and Shiva as lord of the world and master of music was hailed as the soul of nada (sound). In the seventh century the Tamil saint Appar sang of Shiva as Vinadhara in a temple at Valampuram on the coast of Tamil Nadu:

He came holding the vina, the smile upon his lips swept my heart away, he did not turn back to look at me, he spoke enchantingly, he came to Valampuram – there he abides.

(Appar, Hymn 6, 58.6)

Mention should also be made of Shiva as Somaskanda – with Uma and Skanda. Uma, the beautiful goddess and consort of Shiva was frequently represented with the god and their son Skanda. This group was regarded as the principal representation of grace and one of the most popular artistic pieces in Chola temples, as in a splendid bronze in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Typically, Shiva holds an antelope and a battleaxe in his left and right rear hands, a citron in his lower left hand, his lower right hand raised in the gesture of abhaya. Uma clasps a water lily in her right hand; both sit in the lalitsana position. Between them stands Skanda, adorned with jewellery, holding a lotus. In a hymn by Sundarar:

Why settle down here with the lady with the tiny waist! In this town of Murukanpunti...

(Sundarar, Hymn 7, 49.1–3)

These few Shiva types provide a beautiful snapshot of sublime artistic forms in bronze that encompassed a host of other subjects, especially deities, such as Devi Uma Parameshvari (Great Goddess Uma) sometimes in the guise of the fearsome Bhadrakali, the warrior goddess Durga, Ganesha the elephant god, Vishnu, and others; Shiva saints, such as Sambandar, Karaikkal Ammaiyar, Manikkavachakar, and other personalities. All are imbued with the same sensuous elegance, exoticism, spirituality, and a marked femininity that is encapsulated in this abstract artistic genre par excellence. This mastery of the perfect form runs as a common thread through to the larger stone sculptures and the monumental temples that housed them; which were not only treasure houses of artistic wonder, but fused with their venerated subjects as collective wonders of Asian civilisation that was perhaps unprecedented in the realisation of perfection in the realm of art and architecture.