Society in the Kingdom of France in the period of the Ancien Regime was broken up into three separate estates, or social classes: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. These classes and their accompanying power dynamics, originating from the feudal tripartite social orders of the Middle Ages, was the fabric in which the kingdom was woven.

During the reign of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792), the first two estates enjoyed a significantly greater degree of privilege than the third, despite the Third Estate representing more than 90% of the French population and paying almost all taxes. The Third Estate itself was divided between the rising middle class known as the bourgeoisie and the increasingly impoverished working class that came to be known as sans-culottes. As social inequality worsened, tensions between the estates and the Crown, as well as each other, would be one of the most significant causes of the French Revolution (1789-1799). From the meeting of the Estates-General in May 1789 onward, the issue of social classes would remain a dominating theme throughout the Revolution.

Background: The Tripartite Order

Following the final collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, the resultant vacuum in Europe gave rise to feudalism, the hierarchical system that relied on landholdings, or fiefdoms, as sources of power. By 900 CE, around 80% of Europe's arable land was ruled by lords and their families, who had obtained ownership through hereditary claims or military might. This ruling class of landlords, known as the nobility or aristocracy, would rule over serfs, who worked the lords' lands in exchange for military protection. These serfs were usually bound to the lands they worked. The medieval Church held influence over both these groups, with members of the clergy coming from either of the other two orders. At least three-quarters of the bishops and upper echelons of the medieval clergy came from the nobility, while most of the lower parish clergy came from peasant families.

Known as the tripartite order, the three social groups were referred to in Latin as:

- Oratores – those who pray

- Bellatores – those who fight

- Laboratores – those who work

Many 11th- and 12th-century thinkers believed that this was the natural hierarchy of humanity; those who prayed deserved their place of privilege and influence as the protectors of the souls of the community, while those who fought deserved their place as the ruling class by offering stability and protection. The laboring serfs worked the fields of their lords and paid their taxes, completing the final side of this feudal triangle of mutual dependencies.

This tripartite order is not entirely accurate, as it fails to take into account wealthier commoners such as master artisans and merchants, and those who worked in cities. As this outlier group expanded over time to include financiers, entrepreneurs, lay professionals, and lawyers, the gap between these wealthier Laboratores and those still living as serfs widened, and a subgroup of the Laboratores, the burghers, or bourgeois, eventually came into being.

The First & Second Estates: Clergy & Nobility

By 1789, the eve of revolution, the three estates of the realm still constituted the fabric of French society. Aside from the king himself, who was known as "the first gentleman of the realm," every Frenchman was organized into one of the three orders (Doyle, 28). According to French historian Georges Lefebvre, out of the 27 million people who lived in France in 1789, no more than 100,000 belonged to the First Estate, while approximately 400,000 belonged to the Second. That left an overwhelming majority, roughly 26.5 million people, to the Third Estate.

The First Estate wielded a significant amount of power and privilege in Ancien Regime France. Since the king claimed that his authority was derived from a divine right to rule, the Church was closely linked to the Crown and the functions of government. The political and societal power of the Gallican Church was wide-reaching throughout the realm. Since the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, French people were automatically considered to be Catholics, and all records of birth, death, and marriage were kept in the hands of parish priests. Almost the entirety of France's educational system was controlled by the Church; it also had a monopoly on poor relief and hospital provision. The Church also retained powers of censorship over anything lawfully printed. Catholicism, as guaranteed by the Gallican Church of France, was so important that "without Catholic sacraments the king's subjects had no legal existence; his children were reputed bastards and had no rights of inheritance" (Lefebvre, 8). Only in the years immediately preceding the revolution did French Protestants finally begin to see their rights somewhat recognized.

French clergy had organized themselves into a formidable institution, creating a General Assembly, which met every five years to oversee the Church's interests. Such an assembly that represented an entire estate was unique to the First Estate at the time, providing the clergy with their own courts of law. This form of organization allowed the Church to fight off every attempt by the government to limit its financial freedoms, and as a result, clergymen were not obliged to pay any taxes to the state. Instead, the Church routinely gifted a certain amount of money to the Crown in the form of a free donation and sometimes borrowed money on behalf of the state, assuming the interest charges.

The First Estate collected tithes from its own landed property, which was very extensive in northern France. Altogether, the lands owned by the Church constituted about one-tenth of all territory within the kingdom. Additionally, bishops, abbots, and chapters were also lords over some villages and collected manorial taxes.

The Second Estate also enjoyed many privileges. Some were purely honorific, such as the right of the nobility to wear a sword, while other privileges were much more useful, such as the exemption of the nobility from the basic direct tax known as the taille. The justification for this immunity was that the nobles' ancestors had risked their lives to defend the kingdom, paying what was called the 'blood tax' and therefore were not expected to contribute money as well. Yet unlike the clergy, the nobility was not exempted from all taxes, as by the reign of Louis XVI (r. 1774–1792), they were expected to pay poll-taxes and the vingtième (or "twentieth"), the latter of which required every French subject outside clergymen to pay 5% of all net earnings. But even these tax obligations, Lefebvre argues, were watered down by the privileges of the nobility as to not constitute much of a financial burden.

Under the Ancien Regime, the nobility still constituted the ruling class, despite some of their influence and powers having been eroded as the Crown centralized authority during the reign of King Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715). In 1789, the nobility personally controlled one-fifth of all territory in the kingdom, from which they collected their feudal dues. Considered to have been imbued with a natural right to rule on account of their births, aristocrats accounted for all senior administrative ministers, all senior military officers, and almost the entirety of the king's cabinet; the notable exception being Jacques Necker (1732-1804), a Swiss Protestant commoner, who raised quite a stir when he was named Louis XVI's finance minister.

Yet during the reign of Louis XVI, many members of this ruling class of old nobility found themselves drifting away from power. In a society where power was determined by proximity to the king, it became important for those who desired high office to maintain a presence at court in the Palace of Versailles, which constituted a considerable expense. Furthermore, the rise of the wealthy bourgeois class created a wave of new nobility, as rich bourgeois purchased venal offices that ennobled their holders and married their daughters into noble families. Half of the nobility were no better off than the average middle-class bourgeois, and many were much poorer. Some of the old nobility, styled as the nobility of the sword, became envious of the new, wealthy, administrative class of nobles referred to as the nobility of the robe, who they saw as nothing more than jumped-up bourgeois commoners.

To protect the prospects of the nobility of the sword, the French government passed the Ségur Ordinance in 1781, which barred anyone from signing on as a military officer who could not trace noble lineage back at least four generations. Since a military career was a popular path to prestige and esteem, this caused outrage amongst the upper echelons of the Third Estate. At the same time, the old nobility began taking cues from the rising bourgeoisie and some became involved in business, buying shares of industries, granting mining concessions on their properties, or speculating in real estate.

The Third Estate: The Bourgeois & Working Classes

Far from the neatly packaged term of "those who work" that described the third feudal order, the Third Estate of Bourbon France was a messy collection of everyone from the wealthiest non-nobles in the kingdom to the most impoverished beggars. It represented over 90% of the population, but the experiences of those in the upper tiers of the estate were vastly different from those in the bottom tiers. The first subgroup comprised the upper and middle classes known as the bourgeoisie, while the second refers to the working class and the unemployed. During the Revolution, this latter group became known as the sans-culottes (literally "without culottes"), a name denoting their poverty, since only the nobility and wealthy bourgeois wore culottes, fashionable silk knee-breeches.

The bourgeoisie was a steadily growing class. By 1789, about 2 million people could fall into this category, more than double the amount that there had been half a century prior. They controlled a massive share of national wealth; most industrial and commercial capital, almost one-fifth of all French private wealth, was bourgeois-owned, as was a quarter of land and a significant portion of government stock. The wealthiest bourgeois lived lives of luxury, not too dissimilar to the lifestyles of nobles. It was in vogue for a bourgeois family hoping to climb the social ladder to dress in silks, drink coffee imported from the West Indies, and decorate their homes with prints and wallpaper. According to scholar William Doyle, it was primarily bourgeois capital that built theatres in Paris and Bordeaux, just as it was the bourgeois who funded newspapers, colleges, and public libraries.

Doyle credits the rise of the bourgeois in the 18th century to the sudden "extraordinary commercial and industrial expansion” of that period (Doyle, 23). The fortunes of bourgeois families mostly originated from business and were secured through safe investments such as land. Besides Protestants and Jews, to whom social mobility was limited, bourgeois families rarely stayed in the business that enriched them for more than one generation, and money not invested in land would go toward superior education for their children. With this education, "the way was open to the professions, where mercantile origins could be forgotten" (Doyle, 24).

Reaching this status was seen as the goal for many bourgeois families, who would often stagnate on this comfortable, middle-class social rung. Yet not all bourgeois families were satisfied stopping at a middle-class status and, for those who had the money, higher ambitions were indeed attainable. As the financial crisis was becoming increasingly dire during the reign of Louis XVI, the government sold about 70,000 public offices, representing a combined worth of 900 million livres. Some of these venal offices were ennobling, others were hereditary once purchased, but all of them dramatically increased one's social standing. By the means of purchasing ennobling offices, over 10,000 bourgeois bought their way into the nobility during the 18th century.

As the bourgeois grew richer, the poor were getting poorer. Peasants made up 80% of the French population, and many of them lived in the countryside. Poverty and unemployment were rampant amongst this group; even in the best of times, it is estimated that 8 million people were unemployed, and in bad times 2-3 million more might join them. France's fast-growing population meant jobs were becoming scarcer. Wages remained stagnant throughout the century while prices tripled. The unlucky string of bad harvests that struck France during the 1770s and 80s also contributed to the economic woes of farmers, whose financial security was tied directly to the success of harvests. This came on top of the working class already being responsible for most of the taxes.

An influx of peasants moved to cities looking for work. By 1789, 600,000 people lived in Paris, resulting in a rise of thievery, begging, smuggling, and prostitution in the city, as there were not enough unskilled jobs to go around. Many people had no hope of breaking into skilled trades where they had no experience, as these trades tended to be tightly organized. Jobs as domestic servants were especially sought after, since this occupation often came with shelter, food, and clothing, although the popularity of these positions made them exceedingly hard to find.

The sans-culottes were looked down upon by the well-off, who saw the begging and prostitution of the lower classes as a sign of their moral depravity. Monasteries cut back on bread doles given to the needy, on the basis that such handouts encouraged idleness, while hospitals and poor houses began receiving less funding. In 1783, Louis-Sébastien Mercier described the growing divide between the haves and have-nots as such:

The distance which separates the rich from other citizens is growing daily…hatred grows more bitter and the state is divided into two classes: the greedy and insensitive, and murmuring malcontents. (Doyle, 23)

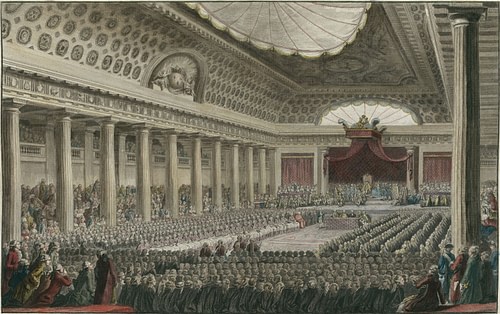

The Estates-General

The Estates-General was a legislative and consultative assembly comprised of the three estates. Although it had no true power on its own and could be called and dismissed by the king at will, the Estates-General allowed the voices of the estates to be heard by presenting grievances and petitions to the king and advising the Crown on fiscal matters. First summoned in 1302 by King Philip IV of France (r.1285-1314), the Estates-General would be intermittently called until 1614, after which it would not sit for 175 years, a period coinciding with the push of the Bourbon kings for centralization of power and absolute monarchy.

In the absence of the Estates-General, the estates were not entirely at the king’s mercy. The First Estate had their own assemblies that they used to protect their interests, while the nobility and the bourgeois relied on the thirteen French parlements, which were appellate courts that oversaw the provinces. Although they had no official legislative powers, these courts did have methods to check and undermine royal power. A royal edict had to be validated by a parlement before it could go into effect in that parlement's jurisdiction, and they also retained a right to protest certain edicts they found unfavorable. The king could circumvent this by issuing a lit de justice which demanded his edicts go into effect regardless of validation by the parlements, but during the 18th century, parlements declared this power to be illegitimate and would suspend all functions of the courts whenever the king attempted to use it. The edict would therefore remain unenforceable until some compromise was reached between Crown and parlement.

The parlements were especially hostile toward financial reform. Under the pretense of protecting the taxpayer, they halted any reform that would limit the financial privileges of the nobility and the wealthier bourgeois. In 1770, Maupeau, the chancellor of France, tried to completely destroy the parlements in order to achieve some financial reform. This did not last long, for when Louis XVI became king in 1774, he restored power to the parlements, and Maupeau was fired.

In 1788, as a financial crisis gripped France, Louis XVI was forced to announce that the Estates-General would convene the following year to discuss tax reform. The announcement caused much excitement, especially after it was revealed that each estate would be represented by an equal number of delegates, as they had been in the 1614 meeting. When the Third Estate demanded double representation due to its much greater population, it was granted this concession. This ended up not mattering, however, as it was announced that each estate would receive only one collective vote each, meaning that the single vote of the 578 representatives of the Third Estate would count the same as the other two estates.

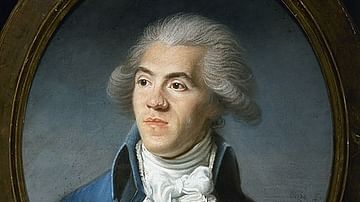

This shifted the discussion away from financial reform and toward the imbalance of societal power. In January 1789, months before the Estates-General was to meet, Abbé Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748-1836) published a pamphlet called What is the Third Estate? In this pamphlet, Sieyès argues that the Third Estate was the only legitimate estate since it made up almost the entirety of France's population and paid most of the taxes. The First and Second Estates, therefore, were dead weight and should be abolished. Sieyès' pamphlet, very popular in the months leading up to the Estates-General, helped shift the conversation toward the rampant inequality in France.

The three estates of the realm, although making up one nation, were vastly different from one another in terms of privilege and power. This disparity, serving as the focus of discussion at the 1789 meeting of the Estates-General, would serve as one of the most significant factors in the French Revolution.