Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE) was a Puritan separatist who believed in and advocated for the separation of church and state, claiming that politics corrupted religion. He advocated for this policy in a number of his written works but, most succinctly, in his 1655 CE A Letter to the Town of Providence in which he compares a commonwealth or community to a ship on which many people of differing beliefs and lifestyles sail toward a common destination. As the captain of the ship may discipline the passengers and crew in the interests of order and common safety but not in matters of religion, so too a magistrate only had authority over civil, not religious, matters.

A Letter to the Town of Providence was written to answer charges by other colonies that Williams advocated a state of anarchy in stressing the ideal of an individual's liberty of conscience in religious belief. No government, he claimed, had the right to dictate the beliefs of the citizens nor to punish them for refusing to conform. Government had the responsibility to maintain order regarding civil matters but no authority to punish people for their relationship with God. His views further distanced him from the other colonies in which church and state were entwined but allowed Providence to flourish as an inclusive religious and cultural center, which became a model for the later government of the United States of America.

Williams' Early Life & Theology

Williams became interested in religion at a young age and initially studied at Cambridge to become a cleric of the Anglican Church. Many of the students at Cambridge at this time had embraced Puritanism – the belief that the Anglican Church was corrupted by the retention of Catholic practices and beliefs and needed to be 'purified' – and Williams followed this same course. The more radical Puritans were known as separatists – those who believed the Church was too corrupt to be saved and sought to separate themselves from it – and Williams eventually adopted this same view.

The Separatists wanted to form their own congregational churches – religious bodies wholly independent from one another, able to make and enforce their own rules apart from a larger church hierarchy – but this was against the law in England. The Anglican Church had replaced the pope as head of the church with the English monarch and so any dissent leveled against the church was treason against the crown. Many separatists fled England for the Netherlands where religious tolerance was practiced, and Williams heard or read of their lives there. He was especially influenced by the Dutch concept of the liberty of conscience – one's innate freedom to pursue whatever religious understanding seemed right to the individual – which was a foreign concept in the England of Williams' time when anyone who did not conform to the precepts of Anglicanism was persecuted.

To Williams, as to all separatists, the only true path a Christian should walk was modeled on the simplicity of the first Christian community as depicted in the biblical Book of Acts. Any additions to the biblical model were not of God and so had to be constructs of the devil. During his time at Cambridge, however, Williams was apprenticed to the great jurist Sir Edward Coke (l. 1552-1634 CE) who stressed the importance in society of equality before the law and just rulings based on empirical evidence. One's religious beliefs, to Coke, had no bearing on one's legal standing; a Catholic who broke the law should suffer the same penalty as an Anglican. Coke's views influenced Williams who, unlike most separatists, extended the concept of equality before the law to religious tolerance and acceptance to others who held non-separatist, and even non-Christian, beliefs.

New England & Banishment

Religious tolerance was not considered a virtue in England under King James I (r. 1603-1625 CE), however, and one of the congregations of separatists who fled to the Netherlands found that even relocating to the city of Leiden did not put them out of his reach. England had established the Jamestown Colony of Virginia in 1607 CE in North America and, by 1620 CE, it was thriving. The Leiden congregation, along with a number of Anglicans hoping to make a new start, sailed for the New World in 1620 CE and founded the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts. The success of Plymouth encouraged others to follow suit, especially Puritans, who continued to be persecuted under Charles I (r. 1625-1649 CE).

In 1630 CE, a fleet of four ships left England carrying 700 Puritan colonists under the leadership of John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE) who delivered a sermon, either just before embarking or en route, stressing the importance of the success of the colony they would establish. Winthrop's A Model of Christian Charity made clear that the colonists had made a covenant with God and needed to conform to a single understanding and act as one to keep their side of the agreement and receive God's blessings. If they failed to do so, they would be mocked by the world and considered deserving of God's wrath.

The government of Winthrop's Massachusetts Bay Colony, although seemingly a democratic Republic, was actually a theocracy in that officials needed to conform to the prevailing Puritan belief system to have any hope of election. Although the Puritans had left England to pursue religious freedom, it was a freedom to which only they felt entitled; those with differing beliefs were not tolerated because dissent threatened the covenant they had made with God.

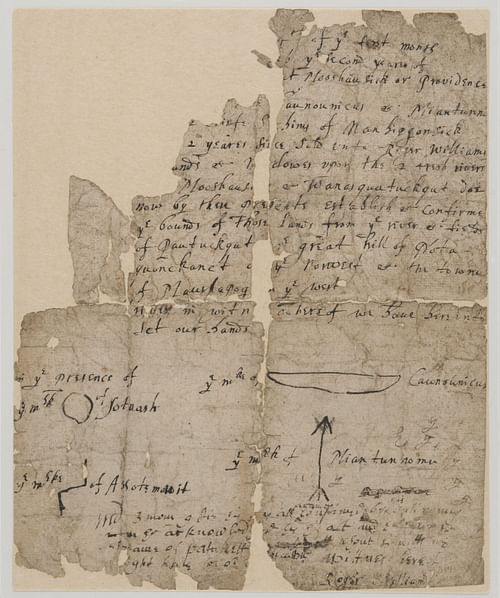

When Williams first arrived, he was welcomed by the magistrates until it became clear his vision did not match their own. He left Massachusetts Bay for Plymouth Colony in 1631 CE but found they were just as legalistic and, further, objected to their treatment of the Native Americans in that they had not paid the natives for the land they had settled. By 1633 CE, he was back in Massachusetts Bay, preaching at a church in Salem, and was called to court to answer charges for 'strange opinions' he was spreading to his congregation.

Williams refused to back down from his claim that the Puritan churches of the colony were intolerant, legalistic, and insisted on following the letter of religious law instead of pursuing the spirit of religious freedom. He was banished and left the colony in 1636 CE, first living among the natives of the Wampanoag Confederacy (whose language he had learned) and then purchasing land from the Narragansett tribe on which he founded his colony of Providence.

Providence Plantation & the Letter

Providence Plantation was informed by Williams' vision of religious freedom for all, a place in which one could follow one's own liberty of conscience wherever it might lead. After Massachusetts Bay Colony banished the religious visionary and dissenter Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643 CE) in 1638 CE, she and her followers were invited to join Providence but chose to settle nearby in what became Portsmouth, Rhode Island. One of Hutchinson's supporters, William Coddington (l. c. 1601-1678 CE), joined Williams at Providence, however, and initially helped develop the colony.

In time, Coddington came to disagree with a number of Williams' views and settled the colony of Newport, becoming its governor and uniting it with Portsmouth in 1640 CE. Coddington and Williams would remain at odds afterwards through disputes over the land and who had legal claim to which areas. Williams returned to England in 1643 CE to procure a legal charter for Providence when it was threatened by Massachusetts Bay Colony with a takeover. He returned with a land patent which united Providence with the other Rhode Island colonies, including Newport, in order to present a united front against any actions taken by Massachusetts Bay against them. Coddington objected to this patent in that he had never been consulted and neither had any of the other colonies.

Arguments and legal actions between Coddington and Williams went on for the next few years. Coddington wanted Newport to be joined to the New England Confederation of Connecticut, Massachusetts Bay, New Haven, and Plymouth which had excluded Providence on the grounds that it was an unruly, lawless, and chaotic community of malcontents, dissenters, and heathens. Williams eventually prevailed and was elected president of the united colonies of Rhode Island in 1654 CE. His letter was written to defend the vision of Providence against its critics, both Coddington and the magistrates of the New England Confederation.

Text of the Letter

The letter was written in 1655 CE after Williams' election. It reads:

That ever I should speak or write a tittle, that tends to such an infinite liberty of conscience, is a mistake, and which I have ever disclaimed and abhorred. To prevent such mistakes, I shall at present only propose this case: There goes many a ship to sea, with many hundred souls in one ship, whose weal and woe is common, and is a true picture of a commonwealth, or a human combination or society. It hath fallen out sometimes, that both papists and protestants, Jews and Turks, may be embarked in one ship; upon which supposal I affirm, that all the liberty of conscience, that ever I pleaded for, turns upon these two hinges–that none of the papists, protestants, Jews, or Turks, be forced to come to the ship's prayers of worship, nor compelled from their own particular prayers or worship, if they practice any. I further add, that I never denied, that notwithstanding this liberty, the commander of this ship ought to command the ship's course, yea, and also command that justice, peace and sobriety, be kept and practiced, both among the seamen and all the passengers. If any of the seamen refuse to perform their services, or passengers to pay their freight; if any refuse to help, in person or purse, towards the common charges or defence; if any refuse to obey the common laws and orders of the ship, concerning their common peace or preservation; if any shall mutiny and rise up against their commanders and officers; if any should preach or write that there ought to be no commanders or officers, because all are equal in Christ, therefore no masters nor officers, no laws nor orders, nor corrections nor punishments;–I say, I never denied, but in such cases, whatever is pretended, the commander or commanders may judge, resist, compel and punish such transgressors, according to their deserts and merits. This if seriously and honestly minded, may, if it so please the Father of lights, let in some light to such as willingly shut not their eyes.

I remain studious of your common peace and liberty.

Commentary

In the first line, Williams makes clear that he never intended liberty of conscience to be equated with licentiousness or neglect of one's civic responsibilities. In doing so, he was purposefully distancing himself from the earlier Merrymount Colony which had been condemned by both Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth Colony for licentiousness and heathenism. The leader of Merrymount, Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE), had been tried, convicted, and deported by Winthrop in 1630 CE. It was important, therefore, that Williams make sure his colony was not being judged as a second Merrymount and that liberty of conscience did not mean liberality in civic duty.

In order to clarify his meaning of the concept, he uses the metaphor of a commonwealth, a state, as a ship which might carry many – "papists and protestants, Jews and Turks" – on board toward a single destination. Throughout the course of their journey together, none of these passengers should be forced to abandon their own faith to conform with that of the ship's commander or officers. In as much as the passengers and crew of the ship cause no trouble to others, they should be left alone to worship and practice other aspects of their faith as they see fit.

Williams then insists that he never defined liberty of conscience as excusing neglect of civic duty or lawlessness. The commander of the ship - or the magistrates of a colony - has every right to punish those who break the law or refuse to work for the common good. Their authority, however, ends with civic matters and has no business with individual religious faith or its practice. He denies that he ever said there should be no magistrates – "no laws nor orders, nor corrections nor punishments" – only that there should be none as far as religion was concerned. He ends the letter in the hope that those who have opposed him and his colony's vision will be enlightened by God and allow themselves to see what he is saying truly rather than what they have been led to believe.

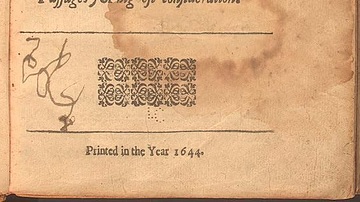

The letter builds on arguments Williams first set down in his most famous work The Bloody Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience in 1644 CE. In this book, Williams presents a dialogue between Truth and Peace over the question of religious practice and tolerance. The book was in answer to the theology and policies of the Massachusetts Bay Colony preacher John Cotton (l. 1585-1652 CE) who initially inspired Anne Hutchinson but then abandoned her during the latter part of her trial and sided with Winthrop and the other magistrates against her. Williams argued that Cotton and the others had no legal right to banish Hutchinson or anyone else for their religious faith and his works, as well as the colony he founded, are the first expressions of the separation of church and state in what would later become the United States of America.

Conclusion

Although his efforts are considered admirable in the present day, they were not received favorably by the other colonies of his time. Williams' claims regarding religious freedom could not be accepted by the leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony who had established their settlement on the understanding of a covenant with God which required conformity to a single interpretation of scripture and resulting practice. To John Winthrop and his magistrates, there was no difference between civil and religious law. Contrary to Coke's assertion regarding equality under the law, to Winthrop a heretic who spoke out against the colony's government was more dangerous than a Christian who had simply become confused or misguided. The Christian, in accordance with scripture, should be admonished and do penance and then be allowed to rejoin the community; the heretic should be banished.

Williams could not, or refused to, recognize Winthrop's understanding of government and Winthrop absolutely could not accept Williams' view without jeopardizing the cohesion of his colony. Winthrop's banishment of Williams, Hutchinson, and the other dissenters, as well as the later executions of Quakers such as Mary Dyer (l. c. 1611-1660 CE) and the other Boston Martyrs by the Puritans, were all to preserve the uniformity of a colony whose magistrates could not allow challenge or change to threaten what they saw as a commission from God. The refusal of the Puritan colonies to change or make any concessions to each other, eventually led to their loss of political power in New England. Williams' acceptance of other views, and the kind of change it inspired, would later encourage the Founding Fathers to base their government on his vision and reject that of the Puritans.