Islam arose as a religious and socio-political force in Arabia in the 7th century CE (610 CE onwards). The Islamic Prophet Muhammad (l. 570-632 CE), despite facing resistance and persecution, amassed a huge following and started building an empire. The tenets of this empire were to be humanitarian and its military might uncontestable. After he died in 632 CE, his friend Abu Bakr (l. 573-634 CE) laid the foundation of the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE), which continued the imperial expansion. Though a feeble force at first, the Islamic Empire soon became the most important influencer in the Middle East and the Mediterranean. Within a few decades, the empire expanded from the city of Medina in Hejaz to engulf all of Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Levant, Iran, Egypt, parts of North Africa, and several islands in the Mediterranean. Internal conflict during the First Fitna (656-661 CE), or the first Islamic civil war, stagnated the empire's borders temporarily but the conquests were resumed afterward by the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE).

The Prophet's Empire

The Islamic Prophet Muhammad started preaching a monotheistic faith called Islam in his hometown of Mecca from 610 CE onwards. Prophet Muhammad was a charismatic and talented person, these qualities augmented by his reputation for honesty allowed him to gather quite a following. Equality, egalitarianism, equal rights for women (who had been hitherto considered “property” by the Meccans), and the prospect of heaven attracted many towards Islam. This change, however, was unacceptable to the Meccans who considered it a serious threat to their economic framework and unfair social stratification.

Despite putting forth strict persecution of the new religion and its preacher, Meccans failed to contain the Muslim community. As the Meccan atrocities became unbearable, Muslims migrated to the city of Medina, in 621 CE, where they had been invited. The Prophet himself arrived in 622 CE alongside his close friend Abu Bakr. Medina offered Prophet Muhammad sovereignty over the city, making him the first ruler and king (r. 622-632 CE) of what was later to become the Islamic or Muslim Empire. The city-state of Medina soon came into conflict with Mecca, and the latter was conquered, after years of warfare, in 629/630 CE.

The fall of Mecca started a snowball event and one after the other, major Arabian cities began submitting to the Prophet's authority as exemplified by Taif, the city that had once mistreated the Prophet for preaching his faith, surrendering in 631 CE. Seeking to retain their autonomy, opposing forces and confederacies made vehement attempts to crush the Muslim forces but were all defeated; a Jewish confederacy was crushed in 628 CE at the Battle of Khaybar, while a Bedouin confederacy was vanquished in 630 CE at the Battle of Hunayn. By the time of his death in 632 CE, the Prophet ruled over an empire in its cradle which was to be further expanded and aggrandized by subsequent rulers.

Dawn of the Caliphate & Ridda Wars

At the morrow of Prophet Muhammad's death, the Islamic Empire slid to the brink of disintegration, as many advocated pre-Islamic home-rule system. This threat, however, was averted when Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE) proclaimed himself the Caliph of the Prophet and the first supreme ruler of the Islamic realm. Back in the days of the Prophet, the Byzantine governor of Syria had murdered a Muslim envoy in cold blood, prompting the Prophet to send an expeditionary force to avenge this injustice and dishonor, however, the force was defeated with severe losses at the Battle of Mu'tah (629 CE). Caliph Abu Bakr's first action was to dispatch another force to avenge the defeat at Mu'tah, as had been planned by the Prophet.

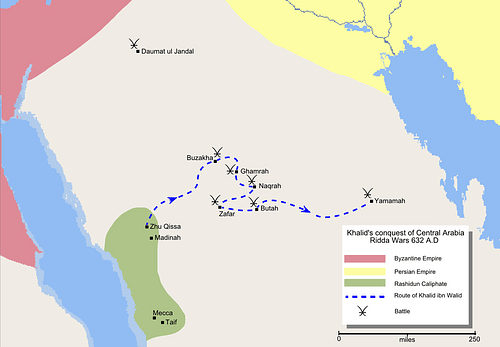

As this force left, the Arabian Peninsula broke into an open rebellion. The Caliph cleverly exploited his foes' disunity and subjugated their forces within a year in what was later termed as the Ridda Wars (632-633 CE). Khalid ibn al-Walid (d. 642 CE), a prominent Muslim strategist, played a pivotal role in this fight by crushing the strongest opposition force under an imposter (false prophet) named Musaylimah in December, 632 CE, at the Battle of al-Yamama. After the defeat at al-Yamama, the rebels could no longer pose a threat equal to what they had in the beginning, and by March 633 CE, order was restored. Abu Bakr had saved his Prophet's empire and religion; for this, he was hailed as a hero and his authority became unquestionable.

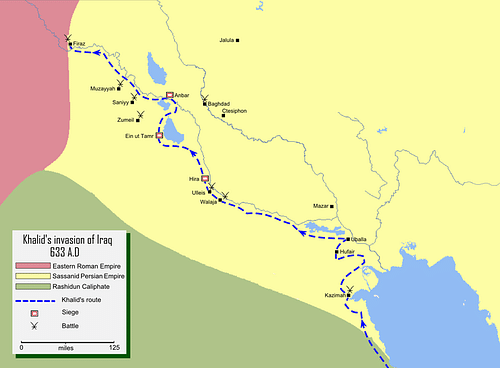

Invasion of Sassanian Persia (Iraq & Khorasan)

During the Ridda Wars, an Arab chieftain named Muthanna ibn al-Haritha approached Abu Bakr and informed him of the vulnerability of Sassanian Iraq. Never content with wasting an opportunity, the Caliph sent Khalid, who had now distinguished himself as a war hero, to raid Iraq (633 CE). The duo stuck to the western side of the Euphrates, where they enjoyed much success, employed eager locals in their ranks, and countered Sassanian advances towards the conquered territory.

Abu Bakr died in 634 CE, and his successor Umar ibn al-Khattab (r. 634-644 CE) took charge as the second caliph of the Islamic Empire and the "commander of the faithful". Caliph Umar reinforced the Iraqi front with fresh troops under the command of a reputable companion of the Prophet: Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas (l. 595-674 CE). Meanwhile, the Sassanians sought to restore their authority over lost Iraqi regions.

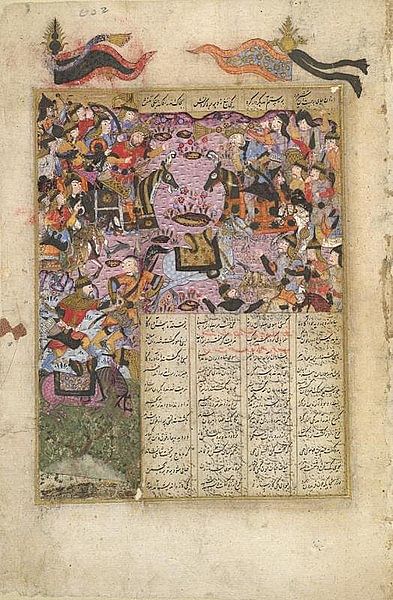

Rustam Farrokhzad, a legendary warrior and a cunning strategist, came out of his respite to face the ever-growing Muslim army. The year was 636 CE, and Sa'd's army was reinforced by victorious troops from Syria. Despite the reinforcements, the Rashidun army was heavily outnumbered and their foe had the advantage in equipment, but the Muslims made up for it with their unparalleled skill in hand-to-hand combat. Rustam thought that his numbers guaranteed him victory and for the first few days of the Battle of al-Qadisiyya (636 CE), it certainly did seem so.

The last Sassanian king, Yazdegerd III (l. 624-651 CE) raised another mighty army to face the Muslims, but this titanic force too was shattered in the Battle of Nahavand (642 CE). Despite this victory, Umar instructed the corps to hold their gains and not to advance further into Iran; he was cautious in this matter and wished not to risk a major setback. The victory at Nahavand brought heaps of war booty to Medina, but with it also came retribution, Caliph Umar was assassinated in 644 CE by a Persian slave named Lu'lu who wished to avenge the losses of his kingdom.

Umar's successor Uthman (r. 644-656 CE) continued the military expansion undertaken by his predecessors. Yazdegerd III, who had escaped to the eastern parts of his kingdom, was murdered by a local at Merv in 651 CE. The last king of the once glorious Sassanian Empire lost his life to treachery, and with his death, died any hope of fighting the Muslim advance. Khurasan was subjugated in a campaign lasting from 651 to 653 CE, and the remainder of the Sassanian lands fell swiftly. The Rashidun Empire spread as far as Sindh, located in present-day Pakistan, to the East.

Invasion of Syria & Levant

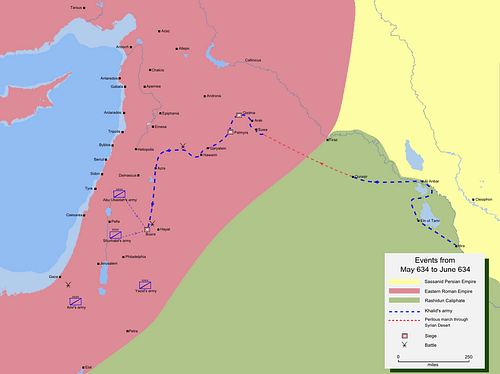

Abu Bakr sent four divisions under Shurahbil ibn Hasana (l. 583-639 CE), Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan (d. 640 CE), Amr ibn al-As (l. c. 573-664 CE), and Abu Ubaidah (l. 583-639 CE) to raid Syria and the Levant. These corps were instructed not to face the Byzantine army in the open or to attack any major cities and castles. Initially successful, these corps soon faced the threat of a major Byzantine force mustered by the ailing Byzantine emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641 CE) and led by his brother Theodore. Not wishing to leave anything to fate alone, Abu Bakr ordered Khalid to advance to Syria.

Khalid handpicked his best men and moved through the trackless desert, using camels as water reservoirs, and appeared on the fringes of Syria. There he united the four divisions and defeated the Byzantine army at the Battle of Ajnadayn (634 CE). When Umar ascended to the office, he dismissed Khalid from his post and placed Abu Ubaidah in charge, probably seeking to assert more control over the campaign.

Khalid, who was not officially in command, was given charge owing to his skill in warfare. The notorious general retreated southwards beyond the Yarmouk river and confronted the imperial army there. The Battle of Yarmouk (August 636 CE) raged on for six days, with the Muslim forces on the back foot initially, but on the climactic dawn of 20 August 636 CE, Khalid ordered an advance and enveloped his foes with his cavalry. The imperial troops routed in panic and faced severe casualties; their field commander probably died in the battle. After this victory, the Muslims swept over Syria, Jordan, and Palestine. Since the Byzantines had given up on the region thereafter, victorious troops were sent to the Iraqi front to reinforce the campaign there.

Before his dismissal, Khalid had led expeditions into Anatolia and Armenia in 638 CE; he died in 642 CE and was buried in Emesa. Abu Ubaidah, who had been placed as the governor of Syria, died in 639 CE in the wake of the plague that devastated the region. In his stead, Muawiya (l. 602-680 CE), the son of Abu Sufyan, a prominent pre-Islamic Meccan aristocrat from the Umayya clan who had later converted, was sent as a replacement. Muawiya effectively took hold of the region and solidified Muslim control over it, and later on, during the reign of Uthman, his cousin and the third caliph (r. 644-656 CE), he conquered all of Armenia (653-655 CE).

Invasion of Egypt & North Africa

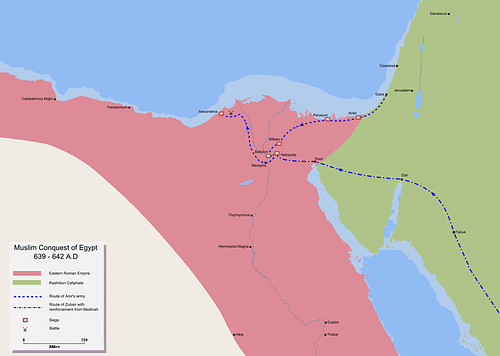

Amr ibn al-As, one of the four commanders originally sent to the Byzantine frontier by Abu Bakr, appeared before Umar with the proposition of another conquest. Egypt had long rested in the hands of the Eastern Roman Empire, but the condition of the people was no different here than it was in the Levant and Syria. Repressive Byzantine policies ensured that an invasion would not be met with stiff resistance.

Umar, however, was not inclined to order an advance, and it took great persuasion on the part of Amr to convince him otherwise. From Egypt, the Byzantines threatened Muslim lands to the north, and with this section cut off from the core of the empire, an invasion would be very effective. Amr, reinforced by Zubayr ibn al-Awamm (l. 594-656 CE), took on an imperial army at Heliopolis (640 CE) and secured a decisive victory.

Naval Operations in the Mediterranean Sea

Honed for their shipbuilding skills, the Syrians were employed to create a formidable Rashidun fleet to challenge Byzantine authority in the Mediterranean. After defeating the Byzantine fleet attempting to retake Alexandria (646 CE), the Muslims went on the offensive. Cyprus fell in 649 CE, followed by Rhodes in 654 CE, and in 655 CE, the Byzantine naval authority was crushed with a victory at the Battle of the Masts. Muslims held uncontested control over the Mediterranean and sent raiding parties as far as Crete and Sicily.

Aftermath & Conclusion

At its peak, the realm of the Rashidun Caliphate spread from parts of North Africa in the west to parts of modern-day Pakistan in the east; several islands of the Mediterranean had also come under their sway. They were a force to be reckoned with and the most important influencer in the region. This initial expansion halted in 656 CE with the cold-blooded murder of Caliph Uthman by renegade soldiers. His successor Ali ibn Abi Talib (r. 656-661 CE) spent his entire reign attempting to restore order to a realm plunged into tumult known as the First Fitna (656-661 CE). Caliph Ali was later murdered by a radical group named the Kharijites in 661 CE, and upon his death, the governor of Syria and his rival, Muawiya, assumed power and gave rise to the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE), who, after facing some initial tumult, resumed the initial conquests.

The Byzantines and Sassanians were superpowers of their time but years of warfare had weakened the two colossal titans. Moreover, Arabs were never expected to pose any threat to them, these disunited desert dwellers did not have the numbers or the will to face an empire. This, however, changed as the Arabian Peninsula was united under the banner of Islam by 633 CE. Freed from the infighting that had plagued them for centuries, the Arabs directed their potential towards their neighbors. They considered a just war as a holy struggle and if death was to embrace them, they would be immortalized as martyrs.

Such a strong resolve, however, was lacking in their foes. Both empires employed mercenaries, and these men did not feel similar passion for their client state as the Arabs did for the Caliphate. Moreover, a multiethnic army lacked the coherence imparted by a single faith and unified national sentiment, but perhaps the most destructive penalty that these empires faced was because of how they treated their people in their provinces. As the Rashidun armies swept over these areas, their numbers swelled with eager volunteers, and many of those who did not fight supported them indirectly. It was also nothing short of a miraculous fortune for the Arabs to have capable military leaders like Khalid ibn al-Walid in their ranks. The early Muslim expansion was ensured by both the strength the Arabs found in Islam and the circumstances under which it happened.