The monastic orders of the Middle Ages developed from the desire to live a spiritual life without the distractions of the world. Men and women who took religious vows were seeking a purity of experience they found lacking as lay people. Their ultimate role model was Jesus Christ who owned nothing and devoted his energies toward others in articulating a vision of communal awareness and self-denial at odds with the human inclination toward self-interest and self-promotion.

Christ's apostles, according to the biblical Book of Acts, followed his example and provided a model for later adherents. The first Christian hermit is generally considered to be Paul of Thebes (also known as Paul the Hermit, l. c. 226-341 CE) who inspired Anthony the Great (also known as Saint Anthony of Egypt, l. 251-356 CE), one of whose epithets is 'The Father of All Monks'. Anthony's life was popularized by the bishop Athanasius of Alexandria (l. c. 296-373 CE) who wrote his biography. This work and others which followed introduced the concept of monasticism to medieval Europe.

Early Hermits & Foundation

Paul of Thebes was a Christian in Egypt who fled his home to avoid persecution and took up residence in a cave near the Red Sea. His initial troubles at home had to do with an inheritance he was supposed to receive which his brother-in-law sought to claim by denouncing Paul as a Christian to the authorities. Paul found the solitude brought him closer to communion with God and let go of his claims on his former life to pursue a new one with only the Divine as his companion.

Some years later, another Christian named Anthony was on his way to services when he thought of the example of Christ and his apostles, compared it to the way the Christians around him were living, and found he could not live that way any longer. He renounced his position, gave away his possessions, and went off to live alone in the desert. In 342 CE, hearing of Paul in his cave, Anthony went to visit him and the two of them ate together. When Anthony returned a few years later, Paul was dead and Anthony received his only garment, a hand-stitched tunic of leaves, which became his only possession.

Saint Anthony's piety attracted others who wanted to learn from him and, eventually, he yielded to their requests and emerged from solitude for six years. He instructed these early adherents in the solitary life of the monachos – those who live secluded from the world – which derives from the Greek mono ('one') and is the basis for the English word 'monk'. After organizing the monks, Anthony again retreated into seclusion until his death.

Constantine the Great (l. 272-337 CE) had legitimized Christianity in 313 CE. Prior to this, Christians were persecuted as the religious minority and many chose martyrdom as the ultimate means of expressing their devotion to God. After Christianity became the state religion of Rome, a Christian did not need to court physical death to prove commitment but the example of someone like Paul of Thebes of Anthony of Egypt was quite compelling: one could die to the world to draw closer to God. Athanasius of Alexandria traveled to Rome in c. 340 CE, bringing with him two of Anthony's disciples and his biography of the saint; and so monasticism was introduced to Europe. Saint Anthony's biography became quite popular and inspired many to follow his example.

Saint Pachomius (l. c. 290-346 CE) was an early founder of cenobitic monasticism ('cenobitic' meaning a community who lives by established rules) on an island in Upper Egypt and his precepts influenced others. The female hermit Amma Syncletica of Alexandria (l. c. 270 - c. 350 CE), who gave away all her riches to the poor to follow God, wrote guidelines for those who emulated her choice to distance herself from the world. She is known as a 'Desert Mother' just as Saint Anthony and others like him are referred to as 'Desert Fathers', early hermits whose example inspired later monastic movements. John Cassian (l. c. 360 - c. 430 CE) established a monastery in Gaul which then encouraged others to do likewise.

Monasteries in Europe

Monasteries in the Early Middle Ages (c. 476-1000 CE) already had rudimentary rules and guidelines set down by Anthony's disciples and other Desert Fathers. Saint Augustine of Hippo (l. 354-430 CE) had written a set of guidelines in a letter for an assembly of nuns in North Africa which became the basis for Augustinian Monasticism (Letter 211). As new orders developed, founders based their rules on Augustine's until the 6th century CE when Benedict of Nursia (l. c. 480-534 CE) wrote his own guidelines which would set the standard for monastic orders going forward. Benedict's guidelines were later advanced by Charlemagne (l. 742-814 CE) who approved the motto Ora et Labora (“Pray and Work”) as the defining characteristic of monastic life.

Benedict's rules emphasized the importance of manual labor and daily prayer as a means of worship and communion with God. Monks prayed eight times a day, beginning before dawn and ending in the evening, when they were not at work or communal activities. Members of a medieval monastery surrendered all their earthly possessions upon entrance, donating them to the order, and renounced any claims to lands, titles, or inheritance. Monks almost uniformly came from upper-class families of wealth as they were expected to make some form of donation to support themselves on entering the order.

Children under the age of ten were also sent to the order and, like their elders, were expected to arrive with a substantial donation. Hildegard of Bingen (l. 1098-1179 CE) was sent to the convent of Disibodenberg when she was seven years old, and the medieval historian-monk Orderic Vitalis (l. 1075-1142 CE) was ten years old when, as he writes, he was led weeping from his father's side in Shropshire to become an oblate (a minor dedicated by his parents to a religious order) at the monastery of Saint-Evroult in Normandy.

The reasons for parents sending their children to monasteries is not always given. Some, like Hildegard's parents, claimed they were simply tithing the ten percent they owed the Church by surrendering their tenth child. These children grew up knowing no other life than the monastery but, at least among those who have left a record of their lives, they thrived there in a way they felt they could never have done in the outside world. Women, especially, found far more opportunities as members of a religious order than in secular life.

The Different Orders

As monasticism flourished, different orders arose which addressed what they considered the most pressing concerns of their time, a certain demographic of the population they felt called to serve, or some different way of honoring God which did not quite fit with other orders. All of these venerated the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, to greater or lesser degrees but each had their own special focus. The best-known cenobitic orders are:

- Benedictines

- Cluniacs

- Cistercians

- Carthusians

- Premonstratensians

- Trinitarians

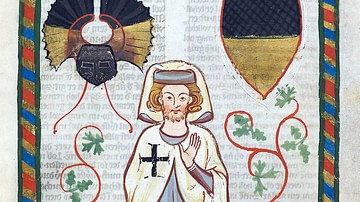

Benedictines were the order founded by Saint Benedict c. 529 CE, although whether he ever intended to found an order and how he intended his guidelines to be used is still debated. C. 580 CE, the Benedictine Abbey of Monte Cassino was sacked by the Lombards and the monks fled to Rome, bringing with them Benedict's rules, and this is how they became so widely disseminated. They are sometimes referred to as the Black Monks for the color of their habits (robes) and were devoted to work and prayer in accordance with Benedict's initial vision.

Cluniacs were a reformed order of Benedictines founded in France at the Abbey of Cluny in 910 CE. The Cluniac Reforms were a response to what was seen as too much interference from nobility in the lives of monks. Many nobles donated land to monasteries as their tithe to the Church or as a means of staking a claim to retire there but then inserted themselves into the lives of the monks and interfered with their daily schedules. The Cluniacs were especially devoted to caring for the poor and those who had been uprooted or left homeless by Viking raids. Their emphasis on art as a means of honoring God resulted in the creation and preservation of many significant works.

Cistercians were another Benedictine order formed in response to perceived abuses and laxity. The Cistercians were founded in 1098 CE at Citeaux Abbey in France by Benedictines who advocated a return to the time of Saint Benedict and a life of austerity. They rejected the Cluniac value of art-as-worship as well as overt patronage from the nobility and focused on manual labor, service to others, and prayer. Their insistence on simplicity in all things gave rise to the form of construction known as Cistercian Architecture which avoids ornamentation in favor of unassuming lines and form. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153 CE) was the most famous Cistercian and a great advocate for simplicity in worship and in one's daily life.

Carthusians were an order emphasizing the value of silence and contemplation. Monks lived in cells, emerging to take part in rituals and work primarily in silence. Certain days of the week were allowed for communal walks in which adherents could speak freely with each other but, for the most part, the monks lived in silence. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne (l. c. 1030-1101 CE) in 1084 CE and was open to both monks and nuns. The monasteries followed the same paradigm as Hilda of Whitby (l. 614-680 CE) at Whitby Abbey in Britain of men and women living separately but worshipping together. The name comes from the site of the first hermitage Bruno founded in the Chartreuse Mountains and the monks continue to be known for the alcoholic drink Chartreuse which they have been producing since the 18th century CE.

Premonstratensians were an order founded by Norbert of Xanten (l. c. 1075-1134 CE) in Premontre, France in 1120 CE. Adherents are not monks or nuns but canons of the Church involved in preaching, evangelical outreach, and teaching. Norbert of Xanten was a friend of Bernard of Clairvaux and Premonstratensian habits and architecture mirror that of the Cistercians in many ways. Their focus is on outreach to local communities through teaching and elevating the thoughts and behavior of others. Although they banned women as members during the Late Middle Ages (c. 1000-1500 CE), they later relented.

Trinitarians (also known as the Order of the Most Holy Trinity and of the Captives) are an order founded in 1198 CE by Saint John of Matha (l. 1160-1213 CE). Their primary function initially was to ransom Christians taken captive by Muslims during the Crusades or through piracy. John of Matha enlarged this vision to provide hospitality for pilgrims, care for the sick or infirm, restoration of church buildings, and evangelical outreach. The Trinitarians were always especially active in their local communities, encouraging education as a form of religious devotion.

Other Orders

In addition to monastic orders centered on a monastery, there were also mendicants (beggars) whose adherents lived lives of abject poverty, transience, and survived by relying on the kindness of others. The two best-known mendicant orders are the Franciscans (founded by Saint Francis of Assisi in 1209 CE) and the Dominicans (founded by Saint Dominic in 1216 CE). The Franciscans emphasized devotion and service to others through a life of simplicity mirroring Jesus' ministry and that of his apostles. The Dominicans emphasized the importance of education and scholarship in apprehending God's will and were also the order primarily involved in the medieval inquisition and suppressing heresy.

The Beguines were an unofficial order which developed in France in the 12th century CE comprised entirely of lay women who felt called to serve God and their neighbors. Their male counterparts were known as the Beghards. The Beguines took no vows and had nothing to do officially with the medieval Church but simply joined a community of like-minded women and devoted themselves to poverty, chastity, and service to others. Women could leave whenever they wanted to and return to their former lives. The Church suppressed and disbanded the order on the grounds they had never approved its existence.

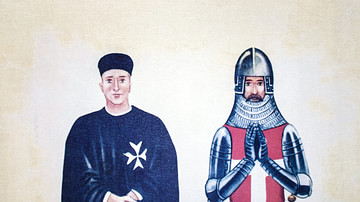

There were also military orders which combined piety with martial skill and combat. The most famous of these were the Knights Hospitaller, the Knights Templar, and the Teutonic Knights.

The Hospitallers (also known as the Order of the Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem) was founded by The Blessed Gerard (l. c. 1040-1120 CE) toward the close of the First Crusade (c. 1099 CE) to care for the wounded, sick, and infirm in Jerusalem. After the crusade, the organization became focused on caring for pilgrims to the Holy Land and, eventually, became a military arm of the Church operating from the island of Rhodes.

The Knights Templar, easily the most famous of the military orders, was founded in 1119 CE by Hughes de Payens (l. c. 1070-1136 CE) and Bernard of Clairvaux who co-wrote The Latin Rule, which defined the appropriate behavior of a Christian knight. The Knights Templar protected pilgrims to the Holy Land and developed financial practices (such as the check and credit) to enable pilgrims and crusaders ease in foreign travel. They were disbanded and systematically destroyed c. 1312 CE through the initiative of Philip IV of France (l. 1268-1314 CE) who was deeply in their debt.

The Teutonic Knights were an order established c. 1190 CE to assist pilgrims to the Holy Land. They established hospitals and cared for the sick while also acting as a military contingent based in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The knights later expanded their efforts into Europe, serving Christians and Christian nobility both as healers and mercenaries. They grew increasingly powerful, seizing lands for their own purposes throughout Eastern Europe, which brought them into conflict with the ruling class. Even so, they managed to not only survive but prosper until the 19th century CE.

Importance & Legacy of Monastic Orders

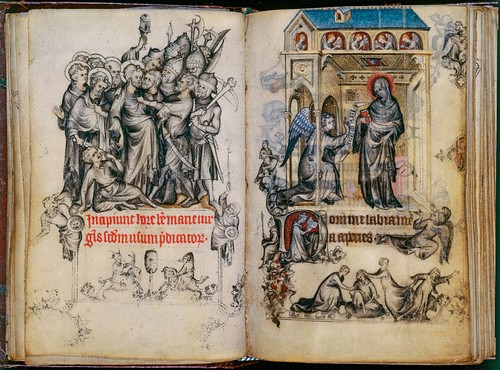

The monastic orders of the Middle Ages are well-known for the production of Illuminated Manuscripts, highly ornamented books on biblical themes or illustrated texts of biblical books, which were highly prized in their day and continued to be throughout the Renaissance and up to the present day. These monasteries also preserved classical works from antiquity by authors such as Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Lucretius, Homer, Sophocles, and other writers whose pieces would otherwise have been lost.

Celtic Monasticism, centered in Ireland, was responsible for the preservation of numerous works of lasting cultural value. Ireland was never conquered by the Roman legions and so was left to develop on its own and, further, was unaffected by the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE. Irish literacy and scholarship were so profoundly respected that Charlemagne consulted the Irish hermit Saint Denis on the meaning and definition of a solar eclipse. The monastic orders, though secluded from mainstream society, nevertheless informed it in many ways. Scholars Rosalind and Christopher Brooke comment:

The 9th and 10th centuries witnessed the beginning of a great revival of the religious life. The monastic cloister was the center of a deeply influential, deeply admired way of life – a ritual life with elaborate liturgy at its center – a life for relatively few dedicated monks, not in itself an expression of popular religion…[but] many of the devotions which flourished in monastic churches became more widely known and more widely diffused – cults of saints and relics, devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and the services in her honor. (48)

The modern-day concept of the hospital, especially in the United States, seems archaic when compared with the same sort of institution established by the monastic orders in which anyone in need was cared for whether they could pay for the service. The development of the Cult of Mary in the Middle Ages elevated women's status to a level previously unknown in Europe. Female monastics - nuns - took part in copying and illustrating manuscripts along with their male counterparts and initiated social programs to help their neighboring communities.

Even though the initial impulse of the monastic adherents was a withdrawal from the world, the monks who lived and worked and died in the monasteries of medieval Europe fundamentally affected society. They established social norms, religious rituals, and church liturgy which, though they seem commonplace in the present day, were entirely innovative in their own.