Alcohol played an integral part in Norse culture. People drank ale more than water because the brew had to be boiled as part of the process and so was safer to drink. The Norse of Scandinavia had four main types of fermented beverage: ale, mead, fruit wine, and syra (basically fermented milk). These were all initially made and served by women and were brewed in the home until men involved themselves in the process and it became a commercial and, finally, religious endeavor once monks became brewers.

Fruit-wine was made from any type of fruit found at hand; wine made from grapes was imported from Germania or Francia and was very expensive. Odin, the king of the gods, drank only wine and was the god of alcohol among his other attributes, but mead was considered the drink of the gods which made anyone who partook a poet or a scholar. Alcohol was so important to the Norse that it was a necessary aspect of formalizing treaties, land deals, marriages, and finalizing the will of the deceased at funerals. Even after the Christianization of Scandinavia, alcohol continued as an important cultural value.

The Brewers

Brewing and serving alcohol was initially women's work and any master brewer would have been female. Eventually, at some point prior to the 11th century CE (when documentary evidence starts appearing on this) men were also brewers. Women, however, were still engaged in brewing and especially in serving alcohol. Historian Mark Forsyth notes:

Serving the drinks was the defining role of women in the Viking Age. In poetry, you didn't call a woman a woman, you just called her a drink-server. There's a thirteenth-century manual on poetry for the aspiring bard. It lays down that: A woman should be referred to in terms of all the types of female attire, gold and precious stones, and ale, wine, and other beverages she pours and serves; likewise in terms of receptacles for ale and all the things that is fitting for her to do or provide. (123)

Mead, ale, and wine were all made in the same way. One would fill a vat with water and set it over a fire and would then add honey and yeast (for mead), bring the mixture to a boil, and then place the open vat beneath some sort of fruit-bearing tree to catch the wild yeast. If one wanted to make ale, one left out the honey and substituted malted barley and, to make wine, one used fruit instead of barley. Alcohol content was regulated by the amount of sugar added which took the form of sap from the trees.

The vat was not air-tight so there was no carbonization. The brew would be left to sit for an unspecified amount of time and then strained into ceramic jugs and stored for later use or sale. The dregs of barley or honey-herb mash left in the vat were then used to make the weaker (less alcoholic) barneol, ale for children. All of these brews were sour because they were fermented in the open air which allowed for bacterial contamination but none seem to have been as sour and bad-tasting as syra.

Syra was made from skimmed milk and rennet (curdled milk from the stomach of a newborn calf). The calf was killed before it had ingested anything other than its mother's milk and the stomach removed and hung up to dry with the milk still in it. Once dried, it was placed in a vat of salt water or whey for two weeks. It was then removed to another vat and mixed with boiled skimmed milk and left to cool (Fernando-Guerro-Rodriguez, 19-20).

This mixture was known as misa (alternately defined as a kind of buttermilk or as curdled milk), which was a popular food, and a by-product of the process of making misa was syra, the liquid skimmed off the misa after it had cooled. The syra was left to ferment for upwards of two years before it could be served. It is said to have been highly acidic and although frequently consumed it does not seem to have been very popular. One would not serve syra to an honored guest, for example, because it was considered the drink of the lower classes who could not afford mead or ale.

Everyone drank ale and, seemingly, every day. Alcohol was the gift of the gods and, just as the gods had shared it with humans, people were expected to share it with each other. The most famous example of this is the party known as the sumbl, a drinking party held by a chieftain in his mead hall, exemplified in the poem Beowulf (c. 700-1000 CE) where Hrothgar hosts a sumbl for his warriors.

Drinking & Social Gatherings

The mead hall was more than just a gathering place; it was a symbol of prestige and power. Any would-be chieftain who wanted the respect of his followers would need to build a mead hall and stock it with the best drink. The yeasty dregs of a good brew were quite valuable and reused to make another batch. The sumbl would be the occasion to show off such a fine ale or mead.

At a sumbl, the chieftain's lady began the festivities by serving a drink to her husband. She would then serve the highest-ranking warriors and then the other guests. Forsyth writes:

You needed a queen because women were a rather important part of the mead hall feast. Women – or peace-weavers as the Vikings called them – were the ones who kept the formal footing of the feast going, who lubricated the rowdy atmosphere and provided a healthy dose of womanly calm. They were in charge of the logistics of the sumbl. (122-123)

The first three drinks of the evening were in honor of the gods and always Odin first, no matter which others then followed. Toasts would have been made to Odin, Thor, and Freyr although Forsyth offers another combination of Odin (in his role as All-Father and as god of alcohol), Njord (god of the sea) and Freyja (goddess of fertility) which is certainly probable considering how important alcohol, sea-faring, and agriculture were to the Norse.

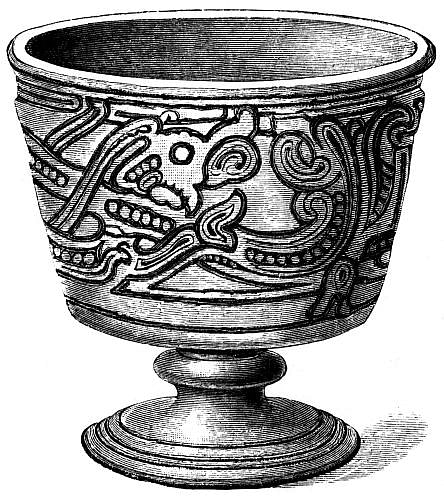

As the evening wore on and people drank more, stories were told which included boasts of great deeds done. The bragarfull was a special cup which one swore oaths on and these oaths were binding. Forsyth notes how, “There was no possibility of excusing yourself the next morning by saying, as we would, that that was just the drink talking. In fact, the reverse was the case” (126). Since drink came from the gods, what one said while drunk was considered true, sacred, and taken completely seriously. Whatever one swore to do while drinking from the bragarfull had to be done within a reasonable amount of time once one was sober.

The sumbl also included gift-giving by the chief to his warriors and guests and then everyone would fall asleep in the hall. The sumbl in Beowulf provides the opportunity for Grendel to murder the warriors with ease because he knows they will all be in a drunken sleep and will offer no challenge. Beowulf is able to defeat Grendel only by remaining sober at the sumbl and feigning sleep.

Besides the sumbl, there were many other occasions for drinking heavily. Marriages were celebrated with alcohol, just as they are today, and ale played an important part in funerals. The funeral feast was known as the Erfi or, more popularly, the Sjaund (which was also the name of the ale served). The family of the deceased would meet with the dead person's creditors and take care of any debts. The deceased's personal property would then be dispersed to the heirs.

There might be arguments, however, over who was supposed to receive what and having ale at hand was thought to be the best solution to this as it would make people merrier and more easy-going. Still, as scholar Martin J. Dougherty points out, ale did not always work and the sjaund “was not always a particularly amicable business and feuds could result” (43). Ale, it seems, could also have the unwanted – but predictable – effect of encouraging arguments.

Business contracts, land deals, and treaties were all concluded with drinks – and the evidence seems to support multiple drinks, not just a symbolic one-cup gesture – and this was to show mutual trust and respect. Wine was used by kings and nobles who could afford it but the most popular and respectful brew to offer at a gathering was mead which was considered so important that it formed the basis of one of the most popular tales of Odin and his adventures.

The Mead of Poetry

Mead is mentioned frequently in the Norse myths. In Valhalla, which is one perpetual sumbl presided over by Odin, the einherjar (Old Norse term for “those who fight alone”, the souls of warriors killed in battle) drink mead continuously as they fight each other in preparation for the great battle of Ragnarok at the end of the world. The mead of Valhalla flows from the udders of the goat Heidrun who eats of the mystical leaves of the tree Laeraor and produces the finest mead, clear and without any residue.

The most famous story about mead, however, is that of the Mead of Poetry. This tale begins at the close of the war between the gods known as the Aesir of Asgard and the Vanir of Vanaheim. To conclude the peace, the gods of both sides spat into a vat and then, not wanting to lose this gesture of goodwill, they take the spittle and create a man named Kvasir. Kvasir was so wise that he could answer any question on any subject whatsoever.

Kvasir left the realm of the gods and went into the world teaching people and answering their questions. He came to the home of two dwarves, Fjalar and Galar, who said they had a question for him but then killed him and drained his blood into two vats (known as Son and Bodn) and a kettle named Odrerir. They then blended honey with the blood and made a magical mead which granted anyone who drank of it the gift of poetry and scholarship (since poetry was associated with wisdom and intellect in Norse culture). When the Aesir came looking for Kvasir, the dwarves told them he had choked to death on his own knowledge because there was no one around to ask him any questions.

The dwarves, who enjoyed mischief more than anything else, later invited the giant Gilling to go boating with them. Once they were out on the water, they tipped the boat so he fell in and, since he could not swim, he drowned. Fjalar and Galar then rowed back home and told Gilling's wife he had died. She cried so loudly that it annoyed Fjalar who had Galar drop a millstone on her head, killing her. Gilling's son, Suttung, heard of his parents' death and went to the dwarves' home, grabbed them both, and stranded them on a stretch of rocks which would be covered at high tide. The dwarves begged for their lives and promised him the magical mead if he would spare them. Suttung agreed, took the mead to his mountain home, and hid it in his daughter Gunnlod's room.

Odin hears of the mead and goes in search of it. He comes to a place where he finds nine slaves cutting hay with dull scythes and offers to sharpen them for him with his whetstone. The slaves are overjoyed afterwards and want to buy the stone but Odin tosses it up in the air and, when the slaves with their now razor-sharp scythes run to grab it, they accidentally slit each other's throats.

The slaves belonged to the giant Baugi, Suttung's brother, and when Odin comes to his home and requests lodging for the night, Baugi is lamenting the loss of his slaves who mysteriously all killed each other. Odin, who is traveling under the name Bolverk (meaning “evil deed”) and is disguised, tells Baugi he can do the work of the nine slaves but will only accept a taste of Suttung's mead as payment. Throughout the summer Bolverk-Odin performs the tasks of the nine slaves and in the fall asks Baugi for his payment.

The two of them go to Suttung's where Baugi presents his case but Suttung will not part with even a drop of the mead. Bolverk-Odin refuses to be turned away so easily and, after pretending to leave, takes out the magical auger Rati and tells Baugi to drill into Suttung's mountain home. Baugi tries to deceive Bolverk-Odin but fails and the god turns himself into a snake and slithers through the hole to Gunnlod's bedroom. He seduces her and stays with her for three nights, gently coaxing her into giving him a taste of the mead. She finally agrees he can have three drinks, one for each night they have been together.

Bolverk-Odin is presented with the two vats and kettle and first drinks the whole kettle and then empties the two vats. Before Gunnlod can do anything to stop him, he turns himself into an eagle and flies swiftly away toward Asgard. Suttung sees him, realizes what has happened, and changes himself into an eagle as well to pursue. Odin the eagle is flying for his life when he is seen by the Asgardians who know he must have succeeded in stealing the mead. They quickly assemble a number of vats in the courtyard of the city and, as Odin flies in, he spits the mead into the vats.

Suttung is close behind him, however, and Odin shoots some of the mead from his rear-end. Suttung flies away and this rear-mead becomes the bad poet's portion. Anyone who tries and fails at poetry (or intelligent conversation) has drunk of this mead. The mead in the vats is the mead of poetry and Odin gives this to the Aesir who then share it with the great poets of Midgard who will sing their praises.

This story is told in the Skaldskaparmal of the Prose Edda, a 13th century CE work which draws on older Nordic material. A version of the story is also told in the Eddic Havamal ('The Saying of the Wise One') and elements of it are depicted in carvings. Scholar Rudolf Simek notes that there are at least these two and possibly a third version of the myth, in addition to its depiction on stones in Scandinavia, and states, “thus, a continuity in the knowledge of this myth is documentarily evident over a period of 500 years and its popularity is evident in the numerous references in skaldic poetry” (209).

The popularity of mead, and the high regard it was given, gave rise to the myth and the myth then further popularized the drink. Mead, ale, and alcohol in general continued as such a vital aspect of Norse culture that not even the later attempts at prohibition by Norse-Christian kings could keep people from it.

Conclusion

In Norway, both King Olaf (later St. Olaf, r. 1014-c.1029 CE) and Eric Magnusson (Eric II, r. 1280-1299 CE) tried to control brewing and selling alcohol for their own purposes. Olaf banned the sale of grains, corn, and malt from the west of Norway to the north in an effort to subdue the northern lords. One of these lords, Asbjorn Siggurdson, went west to get around the embargo because he needed to brew ale for his father's funeral feast.

He was able to buy supplies from the slaves of his uncle Erling Skjalgsson but these were confiscated by Olaf's steward Sel-Thorir. Later, Asbjorn returned to Sel-Thorir's manor while Olaf was there and killed him (and so was afterwards known as Asbjorn Sel's Bane or Selsbani). This event in 1023 CE is thought to be directly linked to Olaf's loss of power and eventual death in 1030 CE. It is assumed that, after his revenge, Asbjorn went on to brew his ale.

Eric Magnusson issued a charter in 1295 CE prohibiting the brewing or sale of alcoholic beverages, as well as drinking parties, outside of established and recognized taverns. Although it is unknown how many people found ways to get around this law, one ingenious group became famous for it. The monks of Norway claimed they needed to be able to brew beer and ale for religious purposes and for the health of their communities; and so they were granted the right.

Beer and ale were both used for baptism and communion under various (unclear) circumstances and a certain priest was known as Thorinn the Keg for either his brewing or drinking skills (Fernando-Guerro-Rodriguez, 53-54). The people of Norway, therefore, continued enjoying alcohol at their weddings, funerals, business deals, and festivals even after the triumph of Christianity over Norse religion; the only difference was that now it was made and blessed by the Christian clergy.