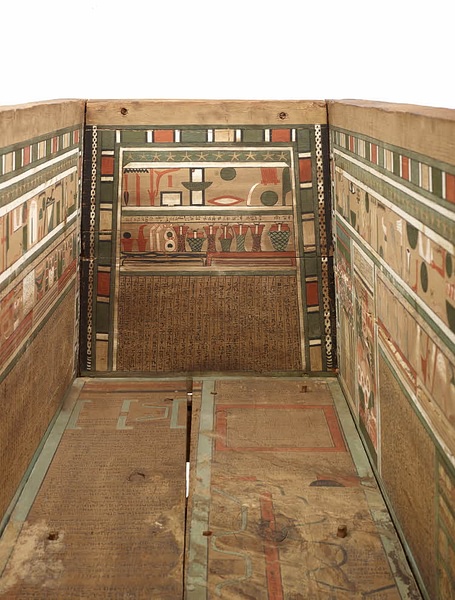

The Coffin Texts (c. 2134-2040 BCE) are 1,185 spells, incantations, and other forms of religious writing inscribed on coffins to help the deceased navigate the afterlife. They include the text known as the Book of Two Ways which is the first example of cosmography in ancient Egypt, providing maps of the afterlife and the best way to avoid dangers on one's way to paradise. Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch notes how "these maps, which were usually painted on the floor of the coffins, are the earliest known maps from any culture" and that the Book of Two Ways "was nothing less than an illustrated guidebook to the afterlife" (15). The Book of Two Ways was not a separate work, nor even a book, but detailed maps which corresponded to the rest of the text painted inside the coffin.

The texts were derived, in part, from the earlier Pyramid Texts (c. 2400-2300 BCE) and inspired the later work known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead (c. 1550-1070 BCE). They were written primarily during the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) although there is evidence they began to be composed toward the end of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) and would continue through the early Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE). In the time of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), they would be replaced by the Book of the Dead which would sometimes be included among one's grave goods.

The Coffin Texts are significant on a number of levels but, primarily, because they illustrate the cultural and religious shift between the Old Kingdom and the First Intermediate Period of Egypt and clarify the development of the religious beliefs of the people.

The Old Kingdom & First Intermediate Period

The Old Kingdom of Egypt is well known as the 'Age of the Pyramid Builders.' King Sneferu (c. 2613-2589 BCE) perfected the art of pyramid building and his son, Khufu (2589-2566 BCE), created the grandest of these with his Great Pyramid at Giza. Khufu was followed by Khafre (2558-2532 BCE) and then Menkaure (2532-2503 BCE), both of whom also erected pyramids at the site. All three of these monuments were surrounded by complexes which included temples staffed by clergy and, additionally, there was housing for the state workers who labored at the site. Although the pyramids are universally admired in the present day, few are aware of the enormous cost of these monuments.

Throughout the period of the Old Kingdom, the rulers not only needed to build their own grand tombs but also maintain those of their predecessors. Giza was the royal necropolis of the Old Kingdom monarchs but there was also the pyramid complex at Saqqara, another at Abusir, and others in between. All of these had to be staffed by priests who performed the rituals to honor the dead kings and aid them in their journey in the afterlife.

The priests were given endowments by the king to recite the spells and perform the rituals but, further, were exempt from paying taxes. As the priests owned a great amount of land, this was a significant loss in revenue to the king. During the 5th Dynasty, the king Djedkare Isesi (2414-2375 BCE) decentralized the government and gave more power to the regional governors (nomarchs), who were now able to enrich themselves at the central government's expense. These factors contributed to the collapse of the Old Kingdom toward the end of the 6th Dynasty and initiated the First Intermediate Period.

During this era, the old paradigm of a strong king heading a stable central government was replaced by individual nomarchs ruling over their separate provinces. The king still was respected and taxes sent to the capital at Memphis, but there was greater autonomy for the nomarchs, and the people generally, than before. This change in the model of government allowed for more freedom of expression in art, architecture, and crafts because there was no longer a state-mandated ideal of how the gods or kings or animals should be represented; each region was free to create any kind of art they pleased.

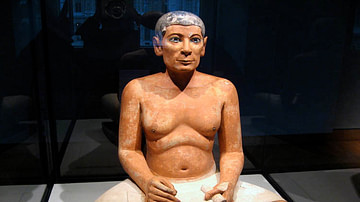

The change also resulted in a democratization of goods and services. Whereas before only the king could afford certain luxuries, now they were available to lesser nobility, court officials, bureaucrats, and ordinary people. Mass production of goods such as statuary and ceramics began and those who could not have afforded the luxury of a fine tomb with inscriptions during the Old Kingdom now found they could. Just as the king once had his tomb adorned with the Pyramid Texts, now anyone could have the same through the Coffin Texts.

The Democratization of the Afterlife

The Coffin Texts were developed to meet the need of a new understanding of the afterlife and the common people's place in it. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick explains their purpose:

The texts, a collection of ritual texts, hymns, prayers, and magic spells, which were meant to help the deceased in his journey to the afterlife, originated from the Pyramid Texts, a sequence of mainly obscure spells carved on the internal walls of the pyramids of the Old Kingdom. The Pyramid Texts were exclusively for the king and his family, but the Coffin Texts were used mainly by the nobility and high-ranking officials, and by ordinary people who could afford to have them copied. The Coffin Texts meant that anyone, regardless of rank and with the help of various spells, could now have access to the afterlife. (502)

During the Old Kingdom, only the king was guaranteed continued existence in the next world. Beginning in the First Intermediate Period, however, ordinary individuals were now thought just as worthy of eternal life as royalty. This era has consistently been misrepresented as a time of chaos and strife, but actually, it was a period of enormous cultural and artistic growth. Scholars who claim it was a 'dark age' following a monumental collapse of the government often cite the lack of impressive building projects and the poorer quality of the arts and crafts as proof.

Actually, there were no great pyramids and temples raised simply because there was no money to build them and no strong central government to commission and organize them, and the difference in the quality of crafts is due to the practice of mass production of goods. There is ample evidence during this time of elaborate tombs and beautiful works of art which show how those who were once thought 'common people' now could afford the luxuries of royalty and could also journey on to paradise just as the king was able to.

The Osiris Myth

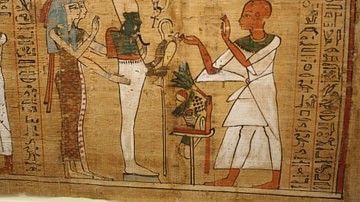

The democratization of the afterlife was due largely to the popularity of the myth of Osiris. Osiris was the first-born of the gods after the act of creation, and with his sister-wife Isis he was the first king of Egypt until his murder by his jealous brother Set. Isis was able to bring Osiris back to life, but he was incomplete and so descended to rule in the underworld as Lord and Judge of the Dead.

The cult of Osiris became increasingly popular during the First Intermediate Period as he was seen as the 'First of the Westerners,' the foremost among the dead, who promised eternal life to those who believed in him. When Isis brought him back from the dead, she enlisted the help of her sister, Nephthys, to chant the magical incantations, and this part of the myth was re-enacted during the festivals of Osiris (and also at funerals) through The Lamentations of Isis and Nephthys, a call-and-response performance of two women playing the parts of the deities to call Osiris to the event. The festival was a ritual re-enactment of the resurrection and anyone attending would spiritually be taking part in this rebirth.

The Spells

The Coffin Text spells and incantations reference many gods (most notably Amun-Ra, Shu, Tefnut, and Thoth) but draw on the Osiris Myth consistently. Spell 74 (A Spell for the Revival of Osiris) re-creates the part of the story in which Isis and Nephthys bring Osiris back to life:

Ah Helpless One!

Ah Helpless One Asleep!

Ah Helpless One in this place

which you know not; yet I know it!

Behold, I have found you lying on your side

the great Listless One.

'Ah, Sister!' says Isis to Nephthys,

'This is our brother,

Come, let us lift up his head,

Come, let us rejoin his bones,

Come, let us reassemble his limbs,

Come, let us put an end to all his woe,

that, as far as we can help, he will weary no more. (Lewis, 46)

Although the words are spoken to Osiris, they were now thought to equally apply to the soul of the deceased. Just as Osiris returned to life through the incantations of the sisters, so would the soul awake after death and continue on to, hopefully, be justified and allowed entrance to paradise.

The soul of the dead participated in Osiris' resurrection because Osiris had been a part of the soul's journey on earth, infused the soul with life, and was also part of the ground, the crops, the river, the home which the person knew in life. Spell 330 states,

Whether I live or die I am Osiris

I enter in and reappear through you

I decay in you

I grow in you...I cover the earth...I am not destroyed" (Lewis, 47).

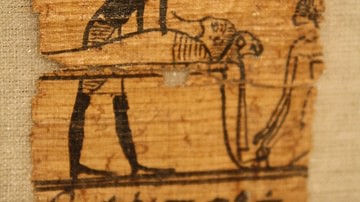

Empowered by Osiris, the soul could begin its journey through the afterlife. As on any trip to a land one has never visited, however, a map and directions were considered helpful. The Book of Two Ways (so called because it gave two routes, by land and water, to the afterlife) showed maps, rivers, canals, and the best ways to take to avoid the Lake of Fire and other pitfalls in the journey. The path through the underworld was perilous and it would be difficult for a soul, newly arrived, to recognize where to go. The Coffin Texts assured the soul that it could reach its destination safely. Strudwick writes, "Knowledge of the spells and possession of the map meant that the deceased, like the pharaohs in times past, could negotiate the dangers of the underworld and achieve eternal life" (504).

The soul was expected to have lived a life worthy of continuance, without sin, and to be justified by Osiris. Directions throughout the text assume that the soul will be judged worthy and that it will recognize friends as well as threats. Spell 404 reads:

He (the soul) will arrive at another doorway. He will find the sisterly companions standing there and they will say to him, "Come, we wish to kiss you." And they will cut off the nose and lips of whoever does not know their names. (Lewis, 48)

If the soul failed to recognize Isis and Nephthys, then it clearly had not been justified and so would meet one of a number of possible punishments. Spell 404 references the soul arriving at a doorway and there would be many of these along one's path as well as various deities one would want to avoid or appease.

Writing & Replacement

Just as the texts themselves represent the democratization of the afterlife, so do the canvases they were painted on. The large sarcophagi of the Old Kingdom were generally replaced by simpler coffins during the First Intermediate Period. These would be more or less elaborate depending on the wealth and status of the deceased. Egyptologist Rosalie David notes:

The earliest body coffins were made of cartonnage (a kind of papier-mache made from papyrus and gum) or wood but, by the Middle Kingdom, wooden coffins became increasingly commonplace. Later, some body coffins were made of stone or pottery and even (usually for royalty) of gold or silver. (151-152)

Scribes would carefully paint these coffins with the text, including illustrations of the person's life on earth. One of the primary functions of the Pyramid Texts was to remind the king of who he had been while alive and what he had achieved. When his soul woke in the tomb, he would see these images and the accompanying text and be able to recognize himself; this same paradigm was adhered to in the Coffin Texts.

Every available space of the coffin was used for the texts but what was written differed from person to person. There were usually, but not always, the illustrations depicting one's life, horizontal friezes of various offerings, vertical text describing the objects needed in the afterlife, and the instructions on how the soul should travel. The texts were written in black ink, but red was used for emphasis or in describing demonic and dangerous forces. Geraldine Pinch describes a part of this journey:

The deceased had to pass through the mysterious region of Rosetau where the body of Osiris lay surrounded by walls of flame. If the deceased man or woman proved worthy, he or she might be granted a new life in paradise. (15)

In later eras, this new life would be granted if one were justified in the Hall of Truth, but when the Coffin Texts were written, it seems one passed through a redeeming fire around Osiris' body. The cult of Osiris became the cult of Isis by the time of the New Kingdom of Egypt and her role as the power behind his resurrection was emphasized. The Egyptian Book of the Dead then replaced the Coffin Texts as the guide to the afterlife. Although tombs and coffins were still inscribed with spells, The Egyptian Book of the Dead would serve to direct the soul to paradise for the rest of Egypt's history.