Roman Philosophy played a significant role in the growth and development of Western thought. While not involved directly in the development of original philosophical thought, Rome made significant contributions in two ways: by conveying Greek philosophy to the people of the Roman Empire and developing the Latin terminology that formed the basis for the spreading of philosophy into the Middle Ages.

Rome was the home of a number of great writers and thinkers: Cicero, Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, among others. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, religion and philosophy became one, and the relationship between faith and knowledge came into question.

From Greek to Latin

Initially, Greek and Latin were the languages of Roman writing: history, poetry, drama, and philosophy. Greek was a second language to most educated Romans, and their sons were still sent to Athens to study both rhetoric and philosophy; most of which was taught in Greek. However, change was on the horizon. In the 1st century BCE, the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius wrote his De rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) in Latin. Both Saint Augustine of Hippo, author of City of God, and Boethius, translator of Plato and Aristotle in the 4th and 5th centuries CE wrote in Latin. The Roman orator and statesman Cicero (106-43 BCE), a Stoic philosopher, translated Greek philosophy into Latin, bringing both its ethics and political theory to Rome. The vocabulary he created was responsible for Latin becoming the primary language over Greek; it remained such until the Renaissance.

According to historian Sara Appel-Rappe ”philosophical development in the Roman Empire deeply influenced how we conceive of Ancient Greek philosophy today” (Companion, 524). She added that in the final years of the Roman Republic, people still studied in Athens, but after the Mithridatic Wars (87-86 BCE), Greek philosophers began to arrive in Rome. However, at that time, Rome still embraced a world "where intellectual aspirations always returned to Greek as the language of choice." The philosophers Calcidius and Apuleius (both Platonists) chose to write in Latin, and gradually, Latin became the chosen language. There were exceptions, of course – in the late 2nd century CE, the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE) wrote his Meditations in Greek because he had been taught in Greek – but Appel-Rappe maintained that philosophy by the 1st century CE, such as the works of the Stoics and the Epicureans, had come to be Latinized.

Although there were adherents to Platonism and Epicureanism – the poet Horace (65-8 BCE) was one – the majority of Roman philosophers, such as Cicero, Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius were followers of Stoicism, a school of philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in the early 3rd century BCE. The Stoics focused their beliefs on the concepts of nature and reason, repressing their emotions and desires, indifferent to pleasure and pain.

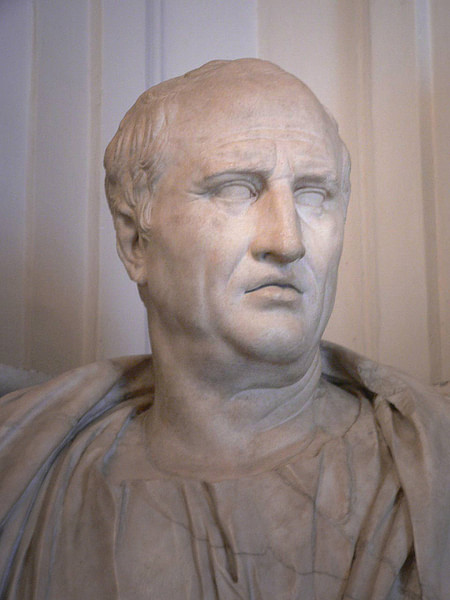

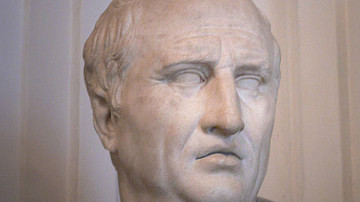

Cicero

In the final days of the old Republic, the Stoic philosopher, orator, and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE) fought for his principles, which would bring a dramatic end to his life. He was born in the small town of Arpinum south of Rome. Early in his career, while practicing law, the outspoken Cicero incurred the wrath of the Roman dictator Sulla (138-78 BCE) and decided for his own self-interest to leave town and study philosophy in Athens. It was there that he was exposed to the tenets of Stoicism. A student of ancient Greek philosophy, much of what is known of Greek thought is due to Cicero's translations of Plato and Aristotle. Stoicism would become the basis of much of his thoughts and writings. He admired the Stoic doctrine of virtue, order, and divine providence. He applied his knowledge of Greek philosophy and its ethical beliefs to both Roman politics and behavior.

Among his many works are the Academica, the De Officiis, and the Tusculanae Quaestiones – the last one was written on Greek philosophy and Stoicism. Lastly, his On the Nature of the Gods (De Natura Deorum) and On Divination (De Divinatione) were concerned with theological issues. While he was critical of some Stoic principles, he considered the Epicureans to be self-indulgent. In a letter to his son, he wrote that they had an advantage when it came to the virtues of wisdom, fortitude, and self-control but failed in the areas of justice and the principles of integrity, generosity, friendship, and courtesy.

After returning to Rome following the death of Sulla, Cicero held various Roman government offices, but he could not support Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) after he assumed the title of dictator. He retired instead to his estate where he began to write his philosophical works. He later justified the assassination of Julius Caesar by calling it a legitimate act of tyrannicide. Having spoken out against Mark Antony (83-30 BCE in his Philippics, Cicero sealed his fate – he was dragged from his home and executed before he could escape. His head and hands were presented to Antony and later displayed on the rostra at the Roman Forum. Like many Stoics, he wrote that one must not fear death: "Wretched is the man to in the course of a long life, he's not learned that death is nothing to be feared.” (On Old Age, 139) He added, "The best end of life comes with a clear mind and sound body when nature itself dissolves the work she has created.” (151)

Seneca

The Stoic philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 BCE to 65 CE) was born in Cordoba, Spain, and lived and died by Stoic principles. He had studied philosophy in Rome but was more interested in Stoic theory than in the political application of its principles – especially when they overlapped old-fashioned republican values. According to historian Anthony Everitt, Seneca's values were expressed in two Latin words: pietas (loyalty and duty) and virtus (bravery and character). Seneca stood in awe of the Greeks, even writing a number of Greek tragedies in Latin, such as Agamemnon, Oedipus, Thyestes, and Medea. At the heart of his personal philosophy was the belief in a simple life and one's devotion to both virtue and reason.

He wrote a number of philosophical essays, such as De Clementia, De Beneficiis, the De Providentia, and 124 letters (Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium). He contended that the only good is virtue and a person can only attain true happiness by acting in accordance with his true nature and must be content with one's lot in life. According to Seneca, the problem with life is not its being short but that a person squanders it. One must not be concerned about the future. Like other Stoics, he spoke of death: "He who fears death will never do anything to help the living. But he who knows that this was decreed the moment he was conceived will live by principle....” (How to Die, 15) In a letter, he said, "Nothing can be of such great benefit to you, in your quest for moderation in all things, than to frequently contemplate the brevity of one's life span and its uncertainty” (11). One must enjoy life and not worry about its being short: "I enjoy my life thus far because I don't spend too much time measuring how long all this will remain ... Death is the undoing of all our sorrows, an end beyond which our ills cannot go: it returns to that peace in which reposed before we were born” (37).

Seneca, the former tutor and advisor to Emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE), was accused of being part of a conspiracy. Although there is no evidence that he was involved, in obeyance to Nero's command, Seneca prepared for his suicide. After contemplating the best methods of committing suicide, he tried bleeding but failed, he tried poison but failed, and so finally his servants put him in a hot bath, and the steam suffocated him.

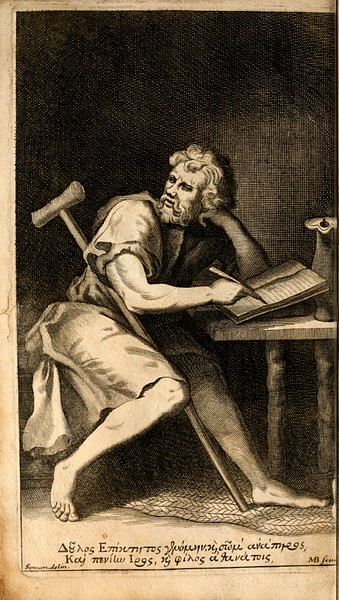

Epictetus

Another Roman Stoic philosopher – one who later influenced Marcus Aurelius – was Epictetus (c. 50 to c. 130 CE). His writings – the Discourses and the Enchiridion – were published posthumously by his student Arrian, the future author and historian of Alexander the Great's campaigns. Born as a slave in Hierapolis, Phrygia, he was made lame by his master Epaphroditus, Emperor Nero's personal secretary. Epictetus was freed upon the death of Nero in 68 CE. While still a slave, he had studied philosophy in Rome with the Stoic Musonius Rufus. Along with other philosophers in Rome, he was banished by the emperor Domitian (r. 81-96 CE); the insecure emperor felt threatened by the growing influence of Rome's philosophers. Epictetus would never return to Rome; instead, he settled in the city of Nicopolis in Epirus where he taught philosophy.

To him, philosophy was a way of life, not just a theoretical discipline. He led a life of simplicity, preferring to live in a hut. "Virtue is our aim and purpose,” he wrote (103). He believed that a philosopher's duty was to help people meet the daily challenges and deal with their inevitability. He encouraged self-control and tolerance of all things. He believed that "Freedom is the only worthy good in life. It is won by disregarding things that be beyond our control” (26). He understood that some things are in one's control and some are not. In one's control are the individual's opinions, aspirations, desires, and the things that repel us.

He taught that a life lived according to Stoic principles was not easy, "for those who pursue the higher life of wisdom, who seek to live by spiritual principles, must be prepared to be laughed at and condemned” (30). However, a life of wisdom is a life of reason where one must learn to think clearly, letting one's reason be supreme: "Conduct yourself in all great and public or small and domestic in accordance with the laws of nature.” (9) To Epictetus, the purpose of philosophy was to "illuminate the way our soul has been infected by unsound beliefs, untamed tumultuous desires, and dubious life choices and preferences that are unworthy of us” (84). The antidote is self-scrutiny applied with kindness. To Epictetus, a happy life is a virtuous life; happiness and personal fulfillment are the result of doing the right thing, as one must bring action and duties into harmony with nature.

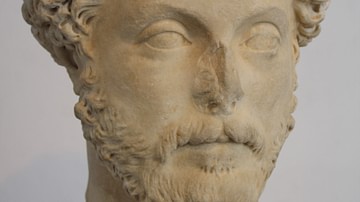

Marcus Aurelius

With little doubt, one of the most prominent adherents to Stoicism was the 2nd-century Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius (l. 121-180 CE), the adopted son of Emperor Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE). A true Stoic, Aurelius wrote in his book Meditations that he sought the truth, "a concept that never harmed anyone; the harm is to persist in one's own self-deception and ignorance” (50). He added that if anyone could prove him wrong and show him his mistake, he would gladly change.

Although it contains a hint of Platonism, Meditations – the last of the Stoic writings – was written while he was on campaign across the Danube. It was a dire time for the empire: natural disasters, famine, floods, and the Antonine Plague, which would ultimately claim the emperor's life. As the last of the five good emperors, some saw Marcus Aurelius as the fulfillment of Plato's philosopher-king. In one of his reflections, he made reference to Plato's four cardinal virtues, a concept that summarized basic Stoic principles:

If you discover in human life something better than justice, truth, self-control and courage, in short, something better than the self-suffering of your own mind which keeps you acting in accord with true reason … then turn to it with all your heart. (14)

Death was a topic explored by both the Stoics and Epicureans: both concluded that one should not fear death, for it was inevitable. "All that exists will soon change. Either it will be turned into vapor, if all matter in unity, or it will be scattered in atoms.” (46) The Stoics believed that death and adversity are out of one's control and come to everyone – one must meet them with dignified acceptance. It is just like birth, a mystery of nature, and one must live in harmony with nature. To Aurelius, "Death is a relief from reaction to the senses, from the puppet-strings of impulse, from the analytical mind, and from services to the flesh” (51).

Like a true Stoic, he realized there was an internal struggle between reason and impulses: appetite, passion, and ambition, but one must pursue them and repel them. He wrote: "Will you ever be complete and free of need, missing nothing, desiring nothing live or lifeless for the enjoyment of pleasure?” (94) Before his own death, he asked himself what he had to fear, writing, "the god who lets you go is at peace with you” (122).