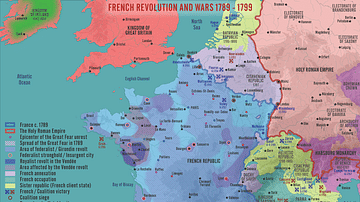

The Revolt of Lyon against the rule of the National Convention was a counter-revolutionary rebellion that played a role in both the Federalist Revolts and the Reign of Terror during the period of the French Revolution (1789-1799). Beginning in May 1793, the revolt ended in bloodshed five months later, when government officials subjected Lyon to a brutal punitive slaughter.

Stemming from concern over the amount of power being centralized in the city of Paris alone, and over the rising supremacy of the extremist Jacobins, the city of Lyon rebelled, imprisoning and executing its Jacobin leadership. In early August 1793, the city was besieged by an army of the First French Republic which began an incessant artillery bombardment that gradually wore down Lyon’s defenses and forced its surrender on 9 October. Upon achieving victory, the Jacobin government in Paris wished to make an example of Lyon and ordered its complete destruction; while this ultimately did not end up happening, close to 2,000 Lyonnais citizens were slaughtered between October and December 1793, as punishment for their city’s treason.

Lyon: Poverty & Insurrection

The Lyon of the late 18th century was a huge city for the time, with a population of well over 120,000. Widely recognized as France’s second city, behind only Paris in terms of population and importance, Lyon was unique in that it was dominated by a single advanced manufacturing industry; namely, that of silk production. For decades, the silk industry in Lyon had been booming, employing the vast majority of the city’s working class, and making Lyon, as well as Lyon’s merchant and bourgeois elite, very wealthy.

Yet, even before the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, Lyon’s silk industry was slowing down. By the time the Revolution was underway, it had practically ground to a halt. The widespread hatred and stigmatization of aristocracy had dealt a massive blow to the silk industry, since many of its potential customers had already fled the country, while the rest knew that it would be dangerous to dress so ostentatiously. Another serious blow to silk production was dealt with the start of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1792; as the list of France’s wartime enemies rapidly grew, the list of foreign markets where Lyon could feasibly sell its goods shrank just as fast.

Consequently, poverty, starvation and widespread suffering quickly became endemic in Lyon. As early as 1790, an estimated 25,000 Lyonnais workers were on public assistance, meaning that somewhere around half of the city’s entire workforce was already unemployed. This only worsened as the Revolution dragged on and inflation rose nationwide. Many Lyonnais factories were forced to shut down, and the cost of everyday goods skyrocketed; by 1793, the price of bread in Lyon was triple the price of bread in Paris.

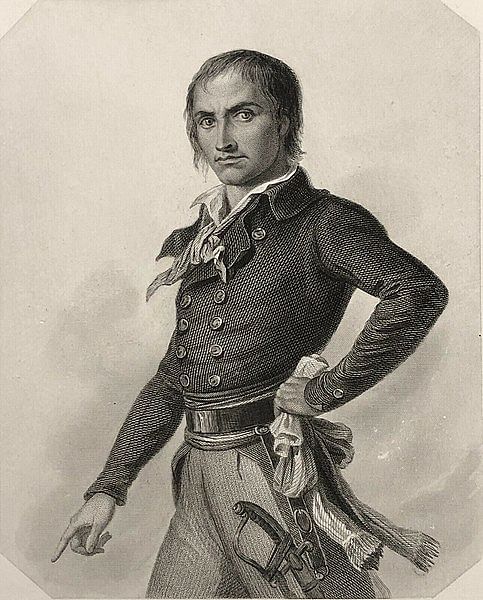

In early 1793, amidst this backdrop of severe hardship, the Jacobins came to power in Lyon, promising to alleviate poverty and help the working classes, now commonly referred to as sans-culottes. The Jacobin-controlled political party known as the Mountain had easily won the municipal elections, in no small part because the city’s established bourgeois elite had been reluctant to dirty themselves with involvement in electoral politics. The leader of these local Jacobins was the fanatical and melodramatic lawyer Joseph Chalier. A diehard revolutionary since the Storming of the Bastille, Chalier had become friends with such Jacobin heavyweights as Camille Desmoulins and Maximilien Robespierre during his time in the capital and was now determined to bring their brand of fiery Parisian Jacobinism to his hometown of Lyon.

It seemed that Chalier followed the example of his Parisian cohorts a little too closely, not realizing that the situations in Paris and Lyon were different. First, he promised to lower the price of bread, but soon found that he could not, since most of the city’s surplus bread had been set aside to provision the armies and his government lacked the funds to procure more. Next, he blamed the city’s silk merchants for the rampant economic depression and unemployment, threatening them with the guillotine if they could not employ more workers. Eventually, Chalier announced that he planned to set up a revolutionary tribunal, declaring that 900 victims were needed to ensure the safety of the patrie (“fatherland”), and that their bodies would be thrown into the Rhone.

Chalier, it seemed, was more adept at making enemies than he was at governing cities. On 24 May 1793, mobs of starving Lyonnais citizens ransacked a warehouse full of provisions meant for the armies. Crowds of women sold them off at what they deemed to be fair prices. To combat these riots, Chalier sent for a detachment of the nearby Army of the Alps to help pacify Lyon. This was the last straw for the city elite, who knew that Chalier could very well make good on his threats if he was backed up by soldiers. They decided to strike first, organizing an insurrection from the city’s working classes, who were angry that the Jacobins had failed to live up to their promises. On 29 May, these insurrectionists invaded the city hall and arrested the Jacobin leaders. Later, on 17 July, Chalier himself was guillotined.

The Siege

Following their coup, the new Lyonnais city government realized it was not enough to cast off the yoke of their local Jacobins alone; seeing as revolutionary power had become so concentrated in the hands of the Jacobins in Paris, it became necessary to cast off the authority of Paris as well. Lyon decided to do exactly that after the fall of the Girondins, the Jacobins’ moderate rivals, from the National Convention on 2 June. Throwing in its lot with the broader anti-Jacobin Federalist Revolts, Lyon declared itself in a state of rebellion and raised an army of 10,000 men. This force was placed under the command of Louis François Perrin, comte de Précy and his cabal of aristocratic officers. Although the federalist movement was still a republican one, Précy and his underlings were avowed royalists, as was a significant portion of the Lyonnais army. As the city’s federalist leaders were not in a position to turn away soldiers, particularly experienced soldiers like Précy, cooperation with royalists became a necessary evil.

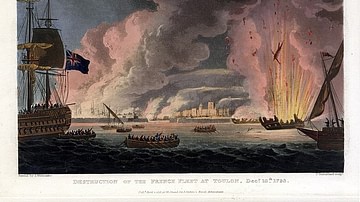

Throughout the city, it was obvious Jacobin retaliation was coming. Thousands of citizens fled into the surrounding hills; these were either Jacobin partisans or apolitical citizens who had no wish to be caught in the coming crossfire. In July, Paris sent detachments of the French Army of the Alps to pacify Lyon. The soldiers arrived on 9 August, encircling Lyon and laying siege. On 22 August, the besiegers began an incessant cannon bombardment that lasted for over a month, destroying most of Lyon’s outlying fortresses and causing much panic and destruction within the city itself. Lyon continued to hold out, relying on the success of a Piedmontese invasion force to push into southern France and relieve the siege. In early October, news reached Lyon that the Piedmontese had been defeated. Their final hopes dashed, it was now clear that the fall of Lyon was inevitable.

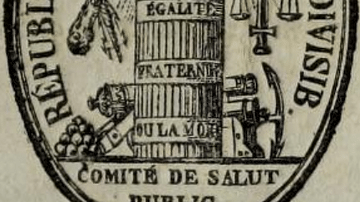

The Jacobin-controlled Committee of Public Safety, now the de facto government of France, sent one of its members, Georges Couthon, to oversee the impending surrender of Lyon. Arriving on 2 October, Couthon immediately called a war council in which he urged a quick and decisive end to the siege. Over the next few days, Jacobin forces intensified their assault, and entered the city itself on 9 October. Most of the defenders, weary from starvation, threw down their weapons without a fight. However, hundreds of the city’s most diehard soldiers escaped with Précy, cutting their way through the Jacobin lines out of the city’s northwest gate. Most of them were killed or captured in the struggle, although Précy himself made it out, eventually going into exile.

The city’s government officially surrendered to Couthon on 9 October. Confined to a wheelchair, Couthon triumphantly entered Lyon in a carriage, passing through the debris-filled streets as hysterical Lyonnais citizens ran alongside him shouting “Vive le Republique,” likely in the hope that they would not be lumped in with the traitors. Upon taking control of the city, Couthon freed the Jacobin prisoners and restored them to their administrative positions; concurrently, he rounded up the federalist leaders and imprisoned them. In an instant, society in Lyon had been flipped on its head, as the pro-Jacobin refugees filtered back into the city, and the bourgeois and merchant elites laid low.

Retribution

Initially, it seemed as though Couthon only wanted to return Lyon to its pre-revolt status quo. He guillotined around 30 of the rebellion’s ringleaders and imprisoned most of the rest. The general population, he decided, had simply been misled, and would be pardoned of their crimes if they recanted their actions and swore allegiance to the Republic. To Couthon, these were fair terms, similar to the ones previously afforded to Caen and Bordeaux which had also been part of the Federalist Revolts.

But Couthon’s colleagues in Paris disagreed with his policy of clemency. Lyon was more reviled in Paris than any of the other Federalist strongholds; it had, after all, defied the Republic for almost half a year, had worked alongside royalists and, worst of all, had murdered Chalier, a true French patriot. On 16 October, the same day Marie Antoinette was executed in Paris, Couthon received a letter from his colleague Robespierre, speaking on behalf of the entire Committee of Public Safety. Robespierre wrote that Chalier “must be avenged, and those monsters unmasked and exterminated” before listing the specifics of the punishment that was to befall Lyon (Schama, 779). The entire city was to be completely and utterly destroyed, reduced to a pile of ash and rubble. Only the houses of the poor were to be left untouched, which were to be renamed “Ville-Affranchie”, or “Liberated City”. On top of the rubble, a column was to be raised which would read: “Lyon made war on Liberty. Lyon is no more” (Palmer, 156)

Couthon attempted to carry out these orders. On 26 October, he was borne on a litter to the place Bellecour, the location of some of the most elegant townhouses in Lyon. Before an assembly of thousands of Lyon’s sans-culottes, he gave a speech in which he condemned the houses to demolition for being the locations where aristocratic plots were made, declaring that,

may this terrible example strike fear into future generations and teach the universe that just as the French nation…knows how to reward virtue, so it also knows how to abhor crime and punish rebellion (Schama, 780).

Following his speech, hundreds of Lyonnais workers descended on the houses with sledgehammers and pickaxes. In the coming months, 15,000 Lyonnais would be employed in the demolition of wealthy houses, paid for at the expense of the rich themselves, against whom a new tax was levied. In total, 1,600 homes were demolished, and the fortifications used by the federalists were razed. But again, this was not enough for Couthon’s more radical colleagues in Paris; it was not the homes of the rich that committed crimes against the Republic, but the people who lived in them. People, not just property, had to be punished. Made uneasy by the weight of his task, Couthon requested to be recalled to Paris. This was accepted, and two others were sent in his place, men who were much more willing to bring retribution to Lyon.

Doom at Lyon

The two men who went to Lyon were not the Robespierrist brand of Jacobin that Couthon was, but were instead Hébertists, a more extreme faction. These men would, in time, become bitter rivals with Robespierre and help bring about his fall. For now, they were his partisans, however begrudgingly, and were sent to do the Republic’s dirty work. Collot d’Herbois was a recent addition to the Committee of Public Safety. Once a struggling actor and playwright, he was now one of the twelve most powerful men in France, an “ultra-radical” whose thirst for blood disgusted the moralizing Robespierre. “The rights of man,” Collot had once said, “are not made for counter-revolutionaries,” (Schama, 781). With him went Joseph Fouché, an ex-professor turned radical republican, cold, quiet, and calculating. For two months, these two men would impose upon Lyon a veritable terror within the Terror, showing the citizens the full force of revolutionary wrath.

Their first act was to impose the Hébertist spirit of dechristianization upon Lyon (also something that Robespierre and his allies detested). All traces of Christian iconography were removed from the medieval clock tower of Saint-Cyr, to be replaced with the new French Republican Calendar. A Festival of Reason was held, in which city notables were forced to prostrate themselves before a statue of Liberty and acknowledge Reason as the one true god. On 10 November, the remains of Chalier were triumphantly carried throughout the streets with the reverence of a martyr; his head was sent to Paris to be interred in the French Panthéon.

Next, Collot and Fouché tightened their control over the city. They imposed a strict curfew, in which citizens had to post a list on their front doors of everyone who resided in their homes. Soldiers would conduct surprise, nighttime searches of random homes, and anyone discovered with an overnight guest would find themselves under suspicion of hiding enemies. Former federalist soldiers who had been pardoned by Couthon were arrested, as was anyone who was suspected of hiding priests or royalist émigrés, anyone who was heard to have defamed the memory of Chalier, or who had otherwise insulted the Republic. Quickly, the prisons of Lyon were filled; they would not stay full for long.

At first, 20 people were being executed by guillotine every day, but this was not fast enough for Collot and Fouché, who set up a special tribunal to speed things along. Within days of the tribunal’s creation on 27 November, 300 new death sentences were handed down and rapidly carried out. The executioners worked with great efficiency; on one day, 33 people were beheaded in only 25 minutes. A week later, 12 heads fell in just five minutes. On 4 December, it was reported back to Paris that 113 inhabitants of “this new Sodom” were dispatched in a single day (Schama, 783). Before long, citizens began complaining of the blood overflowing the drainage ditch that led from beneath the scaffold. When a German observer asked a guard if the blood would be cleared from the street, the guard allegedly responded, “Why should it be cleared? It’s the blood of aristocrats and rebels. The dogs should lick it up” (Doyle, 254).

Even this astonishing speed of the guillotine was too slow for Collot and Fouché. Just as their colleague, Jean-Baptiste Carrier, was concurrently busy submerging thousands of counter-revolutionaries in the Loire River in the Drownings at Nantes, Collot and Fouché decided that they, too, needed an alternative method of execution. Eventually, they decided to take large groups of prisoners out to the Plaine des Brotteaux, just outside the city. As many as 60 prisoners at a time were roped together and fired into point blank by cannons loaded with grapeshot. Those who were not instantly killed were finished off by the sabers and bayonets of the guards. Known as mitraillades, hundreds of citizens were killed this way, mostly between 4-8 December.

Aftermath

In late December 1793, Collot d’Herbois and Joseph Fouché were recalled to Paris, as the National Convention had become horrified by the rumors of their atrocities. Tensions continued to rise between the Robespierrists and the butchers of Lyon, until Collot and Fouché helped to bring about the fall of Maximilien Robespierre, the event that ended the Terror. Collot was never able to shake off the calamitous reputation he had earned at Lyon. In 1795, he was denounced and deported to French Guiana, where he died of yellow fever a year later. In contrast, the more cunning Fouché would continue climbing the political ladder, becoming Minister of Police during the reign of Napoleon only to eventually die in exile following the Bourbon Restoration of 1815.

Despite the Committee of Public Safety’s orders to obliterate Lyon, the city did not suffer too much external damage. After the Terror, the destroyed houses were rebuilt. During the Napoleonic period, Lyon’s economy would not only recover, but skyrocket, as the demand for silk returned with a vengeance, and new market opportunities were created along with the expansion of French imperial influence.

The psychological damage on Lyon’s population, however, was not so easily erased. Most people had known or loved someone directly affected by the Terror, and hatred of Paris continued to exist in Lyon for generations. All told, 1,905 people had been killed in the months following the Siege of Lyon. While Jacobin propaganda painted the victims as local nobility, federalist officers, or royalist sympathizers, this was only a partial truth; hundreds of working-class citizens also went beneath the scaffold, for one perceived counter-revolutionary offense or another.

Dispelling the common notion that Lyon had been purely a class conflict, historian Simon Schama notes the specific working-class occupations of many of the executed; 40 were journeymen weavers, while others included locksmiths, cobblers, innkeepers, chocolate makers, doctors, and servants among others. Even the city’s executioner, Jean Ripet, was himself killed in retaliation for the execution of Chalier, but only after his weeks of labor executing the Jacobins’ enemies. The aftermath of the Revolt of Lyon is therefore remembered as one of the bloodiest instances of mass slaughter to be carried out during the period of the Reign of Terror.