Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) was a conflict between the Lakota Sioux-Cheyenne-Arapaho alliance and the US government over the westward expansion of the United States into the Powder River territory. It was the only war won by the Plains Indians and it halted further US expansion in the region until the Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876.

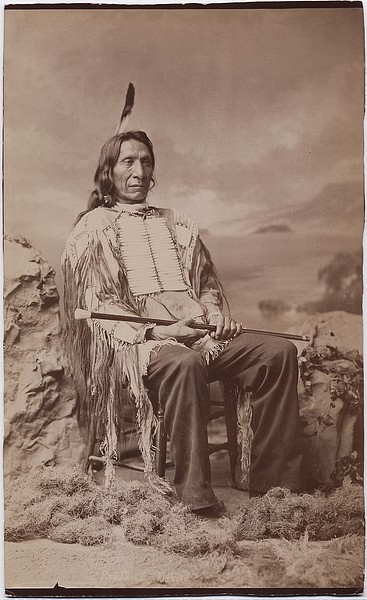

Red Cloud (Makhpiya-luta, l. 1822-1909) was an Oglala Lakota Sioux chief, who opposed white settlement of Sioux lands, the opening of the Bozeman Trail in 1863, and especially, the construction of garrisoned forts in the region to protect settlers from Native American attacks. He at first understood the Bozeman Trail as a thoroughfare that allowed white settlers to pass through Sioux lands, but after realizing that forts would be built to defend the trail, he organized a war party to drive the whites from the region.

He waged a guerilla war beginning in 1866, targeting military and civilian workforces, and won his greatest victory in the engagement known as the Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands, Battle of a Hundred Slain, the Fetterman Fight, or the Fetterman Massacre of 21 December 1866. Other famous engagements are the Hayfield Fight (1 August 1867) and the Wagon Box Fight (2 August 1867), but all three of these are only the best documented of the many attacks organized and executed by Red Cloud.

In 1868, the US government sought peace, recognizing they could not defeat Red Cloud, and the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 was signed between the two parties, establishing the Great Sioux Reservation (all of modern-day South Dakota, part of North Dakota, and part of Nebraska) and promising the land to the Sioux forever.

In 1874, however, an expedition led by Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876) discovered gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota and the US government ignored the treaty of 1868, leading to the Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876 and the Great Sioux War (1876-1877). Red Cloud did not participate in this war, having chosen to fight for Native American rights through the legal system instead of military conflict.

Background & Early Hostilities

The Powder River region (in modern-day northeastern Wyoming) had been claimed by the Crow nation until 1820 when the Cheyenne, allied with the Lakota Sioux, defeated them in the engagement known as the Tongue River Massacre. The Sioux then expanded the territory, fighting wars with other nations including the Kiowa, Pawnee, Ute and, of course, the Crow.

Around 1825, white settlers arrived in the region, and by 1835, they had established the Fort William trading post. Conflict between the different Native American nations and between bands from various nations and white settlers over land rights resulted in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 which defined and allotted specific areas to the different nations. According to the Crow, the Powder River Region was theirs, but in keeping with the tradition of Native American warfare, it now belonged to the Sioux who had defeated them in 1820. The treaty sided with the Crow, who were on good terms with the US government.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 promised all the lands in question would be regarded as 'Indian Territory' and made clear the United States had no claim to them. In 1858, however, Pike's Peak Gold Rush carried an influx of white prospectors to the region of modern-day Colorado, ignoring the treaty, and bringing the miners and settlers into conflict with Native American nations.

As more settlers arrived, more natives were displaced and fought with each other for prime hunting grounds and, at the same time, the US government was encouraging white hunters to slaughter the buffalo of the Great Plains, and, as the buffalo were the major source of food and clothing for the Plains Indians, this led to further conflict between the nations over fewer resources.

A major article of the 1851 treaty stipulated that Native Americans would allow white settlers to pass unmolested along the Oregon Trail but, even with treaties that were signed by chiefs with the authority to do so, the US government consistently made the mistake of thinking that the signature of the chief of one band of a nation guaranteed the compliance of all citizens of that nation.

Red Cloud, for example, was regularly referenced as the Chief of the Sioux but was actually only the leader of the band of Sioux known as the Bad Faces. As such, he could only speak for the Bad Faces, not the entire Sioux nation and not even another band. Some bands honored the 1851 treaty, others – whose chiefs had not signed or had never even heard of it – did not.

In 1863, gold was discovered in Montana and the Bozeman Trail was opened to allow easy access. According to the United States' understanding, this was Crow territory, and the Crow observed the 1851 treaty, including the stipulation that the US could build forts in the region. According to the Sioux, this was Sioux territory, and they had never agreed to the construction of forts or, according to some bands, even respecting the right of passage along the Oregon or Bozeman trails. In 1865, the US Army launched the Powder River Expedition to subdue the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux, but it accomplished nothing except to provoke these nations further.

Fort Laramie Council & War

In June 1866, US representatives managed to bring the leaders of the hostile nations to the negotiating table at Fort Laramie. Among the Sioux delegates were Red Cloud and another Oglala Lakota Sioux chief, Young-Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses (a mistranslation of Tasunka Kokipapi, He-Whose-Horse-is-Even-Feared, a reference to his reputation as a warrior, l. c. 1836-1893). Red Cloud had allowed white settlers to cross Sioux land but had never agreed to permanent settlements.

The negotiations were joined by the newly arrived Colonel Henry B. Carrington (l. 1824-1912), who had orders to establish forts in the region to protect white settlers. On realizing the US intended to build permanent settlements in Sioux land without permission, Red Cloud and his delegation angrily left the meeting. Red Cloud then began calling together a war council to discuss what should be done.

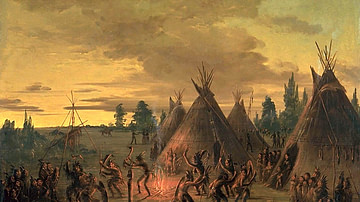

In the following months, while Carrington and his command built and fortified Fort Phil Kearny and Fort C. F. Smith, Red Cloud and the Sioux, with their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies, launched his war. Scholars Bob Drury and Tom Clavin describe a war council held in November 1866, taken from first-person Native American narratives, which would have been similar to those held earlier in June.

There, on the sandy banks of Goose Creek where it flowed in the icy Tongue, Red Cloud gathered his warrior societies about him to finalize his plans to drive the white man from the Powder River Country and defeat the mighty United States in the only war the nation would ever lose to an Indian army. The great chief summoned the spirits of his dead forefathers to weave a tale of Indian survival, of Indian hope, of Indian victory. He insisted that the red man had been granted this land by the Great Spirit, as a birthright that had been theirs forever and would be theirs forevermore, in this life or the next. When he finished his speech, more Indians spoke, and the campfires were banked before the pipe was passed and the war dance begun. And then, through billows of blue tobacco haze, Red Cloud retired to a warrior lodge erected in a copse of cedars along the river's edge. There he laid out for his battle commanders his strategy for the final destruction of the white interlopers and their forts in the Powder River Country. (15)

Red Cloud, then, became the recognized war chief of this particular war party, and this would later be misunderstood by Euro-American writers who referred to him as the Chief of the Sioux. As war chief, it was Red Cloud's responsibility to plan and execute engagements with the enemy, and in mid-July 1866, he went directly to work.

Carrington's Command & War

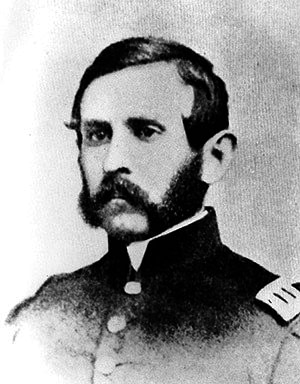

Colonel Carrington was a bureaucrat who had served as an administrator on the Union side during the American Civil War but had no experience with armed conflict. Before service, had had been a lawyer with an interest and skill in engineering. He was ordered out west in 1866 to build the forts along the Bozeman Trail specifically for his administrative and engineering skills and accepted the position to further his military record in commanding a post in hostile territory.

His second-in-command was Captain William J. Fetterman (l. c. 1833-1866), who did not arrive at Fort Phil Kearny until November 1866. Fetterman had commanded Union forces in battle between 1861 and 1865 and been highly regarded by his troops. Fetterman seems to have had little respect for Carrington from the start, owing to the difference in their wartime service, and what little he had evaporated under what he considered his commanding officer's timid approach in dealing with Native American hostilities.

Of the 700 soldiers under Carrington, 500 were new recruits with no battle experience, and most of the others had never fought against Native Americans. Along with the soldiers, Carrington was responsible for around 300 civilians who would help build Fort Phil Kearny and other posts, cut and haul the wood, and make regular trips outside of the fort to cut hay to feed the horses and livestock. The wives, children, and other dependents of the soldiers and civilians – as well as the regimental band – made up the remainder of the fort's residents.

Since the US government, in accordance with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, understood the land to belong to the Crow and, since the Crow were regarded as 'friendly Indians', Carrington's command was not outfitted for war, but for the construction of forts. They were consequently not supplied with the best weaponry – such as the Spencer repeating rifle – and his infantry were all armed with the much cheaper Springfield muzzle-loading musket. Among the most significant differences between these two weapons was that the Spencer could fire up to 20 rounds per minute while the Springfield fired up to 3 rounds in that same time. Only the cavalry and some civilians had the more advanced weaponry.

Fort Reno was already established by the time Carrington reached the region, and he then began construction of Fort Phil Kearney and Fort C. F. Smith. He divided his command between the forts with 100 at Fort Reno, 200 at Fort C. F. Smith, and 400 at Fort Phil Kearny. Contingents of soldiers would accompany civilian details outside the fort for woodcutting and haying.

Red Cloud began by targeting these details as well as harassing the forts and running off horses, mules, and cattle. He could send a strike force against Fort Phil Kearny and simultaneously against Fort C. F. Smith 91 miles (146 km) away, and, at the same time, intercept wagon trains bringing supplies and attack settler's wagon trains on the Bozeman Trail. When troops pursued, the attackers vanished away into the wilderness. Casualties steadily mounted throughout the summer, mostly among civilians, and travel along the Bozeman Trail had been abandoned by the end of July 1866.

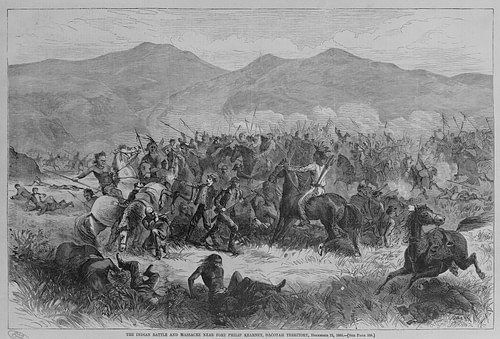

Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands/Fetterman Massacre

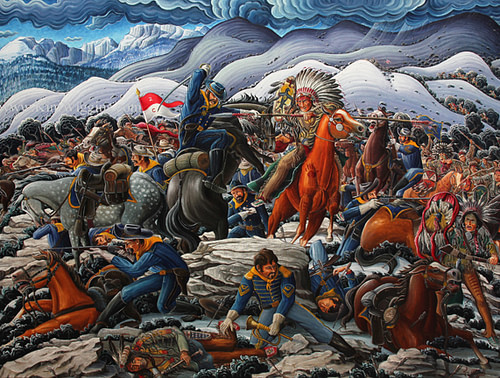

By the fall of 1866, Red Cloud had perfected his tactic of decoy-ambush-vanish and, on 6 December, killed several troops from the 2nd Cavalry, along with their commanding officer, when the cavalry had taken the bait of his decoys and pursued them over Lodge Trail Ridge, an area far enough away from Fort Phil Kearny to prevent quick deployment of reinforcements. To draw troops out of the fort, Red Cloud kept up his assault on woodcutters and hay details, and on the morning of 21 December, a wood train was attacked, and Carrington ordered Captain James Powell to lead a relief force. Fetterman objected, however, noting that he outranked Powell, and so command was given to him.

According to his later reports, Carrington ordered Fetterman to only relieve the woodcutters and return to the fort and under no circumstances to pursue the hostiles over the Lodge Trail Ridge. Lt. George W. Grummond, who agreed with Fetterman in criticizing Carrington's passive leadership, took command of the cavalry detail. Allegedly, Carrington repeated the same orders given to Fetterman to Grummond before the 81-man relief force left the fort.

What happened next and why continues to be debated, but based on the accounts by Carrington and others, including later Native American eyewitnesses, Fetterman ignored the orders and, instead of proceeding directly toward the woodcutters, he cut to the north in the direction of the Lodge Trail Ridge. He encountered the young warrior Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877) and a small band of others who rose on their horses and mooned and mocked the troops before riding off. Grummond seems to have led a cavalry charge over the ridge and down into the same valley where the 2nd Cavalry had been ambushed on 6 December, with Fetterman's infantry following close behind. Once they had crossed the ridge, Red Cloud unleashed a force estimated between 1500-3000 warriors upon them, and Fetterman's entire command was killed in less than an hour.

Carrington, hearing the sound of weapons fire, sent out another relief force under Captain Ten Eyck, who, encountering another band of decoys, refused to take the bait and waited for them to disperse. After he reached the valley and found all of Fetterman's command dead, he noted, unsurprisingly, that those with the more advanced weapons had held off their attackers longer. All of the soldiers had been stripped and mutilated in keeping with the Native American belief that one's spirit entered the afterlife in the same form one had left behind on earth. Cutting off an enemy's hands, feet, tongue or other parts made sure they lacked those same when they reached the other side and so would not be able to enjoy the pleasures of the afterlife. The only soldier whose body remained intact was the bugler, Adolph Metzger, who – unarmed, as buglers were – fought off the enemy with only his instrument. His body was found covered by a buffalo hide as a sign of respect for his courage.

The engagement became known to the Sioux as the Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands because before the battle Red Cloud had called upon a Two-Spirit (a third gender both male and female) of his people, understood to possess especially strong spiritual powers, to approve of the site for the ambush. The Two-Spirit, after performing a ritual, reported he had received a vision in which he held 100 soldiers in each hand. The battle became known through 19th-century newspapers throughout the USA as The Fetterman Massacre.

Conclusion

Red Cloud dispersed his war party for the winter but renewed his attacks in April 1867. Between April and July, he repeatedly struck at the forts, the civilian work details, supply wagons, and wagon trains attempting to cross the Oregon Trail. In August 1867, he struck at a civilian detail gathering hay outside of Fort C. F. Smith. His warriors were used to facing the same muzzle-loaders the soldiers had used before, but after the Fetterman Fight, updated rifles had been issued to the fort. Instead of the 30-second to one-minute interval between shots of the muzzle-loaders, the breech-loading rifles could fire repeatedly. Consequently, the Hayfield Fight and Wagon Box Fight (near Fort Phil Kearny) of the next day were both victories for the defenders.

Red Cloud adapted to the new weaponry, however, and continued the war into 1868. By August 1868, Fort Reno and Fort C. F. Smith were abandoned, and troops were pulled back to Fort Phil Kearny. Red Cloud ordered the abandoned forts burned. The US government recognized there was no way to win this war against an opponent who could appear without warning anywhere, strike effectively, and disappear and so finally sought peace. Red Cloud signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 in November, establishing the Great Sioux Reservation, closing the Bozeman Trail permanently, and ending the war. Fort Phil Kearny was abandoned and afterwards burned.

In 1870, Red Cloud traveled to Washington, D.C., meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant (served 1869-1877), and then again in 1875 – after gold had been discovered in 1874 in the Black Hills that were sacred to the Sioux, initiating what would become the Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876 – advocating for the rights of his people. Although his claims were ignored, Red Cloud continued to press for recognition of Native American rights through the legal system for the rest of his life, refusing to resort again to war. Drury and Clavin comment:

On December 10, 1909, Red Cloud died peacefully in his sleep at the age of eighty-eight. His death prompted headlines around the country. In a lengthy appreciation, the New York Times noted, "When Red Cloud fought the whites he did so to the best of his ability. But when he signed the first peace paper, he buried his tomahawk, and this peace pact was never broken." It was, of course, broken many times – by the US government. (363)

Red Cloud's descendants and others have repeatedly pointed this out right up to the present day, but the US government continues the same policies it maintained in the 19th century of making promises it has no real intention of keeping. The Land Back Movement and other organizations are presently continuing Red Cloud's legal battles to restore the lands illegally taken to their rightful stewards.