Phoenician Architecture is typified by large temples with double-columned facades approached by a short staircase, enclosed sacred spaces containing cube-like and open-fronted shrines, and such large-scale engineering projects as dams and artificial harbours. High fortification walls included square towers and gates, and were built of mud-bricks and limestone, as were more the modest domestic buildings. The paucity of archaeological remains from the period when Phoenician cities were at their height makes general statements dangerous, but it is possible to say that Phoenician architects were relatively austere and sparing in the use of decorative elements both inside and outside their buildings.

Sources

The study of Phoenician architecture is beset by two problems from the outset. Firstly, having access to abundant cedar forests, it is likely the Phoenicians employed wood for most of their buildings, an unfortunate choice for posterity as wood is not, of course, as great a survivor as stonework. The second problem for historians is that Phoenician cities have been in constant occupation throughout their history which makes archaeological excavations problematic. Although very few remains have survived of Phoenician buildings and we know very little of more modest structures such as ordinary housing, we do, though, have descriptions of larger public buildings from such sources as Herodotus, Strabo, Arrian, and the Bible, and some archaeological evidence of smaller shrines both in Phoenicia and its colonies across the Mediterranean.

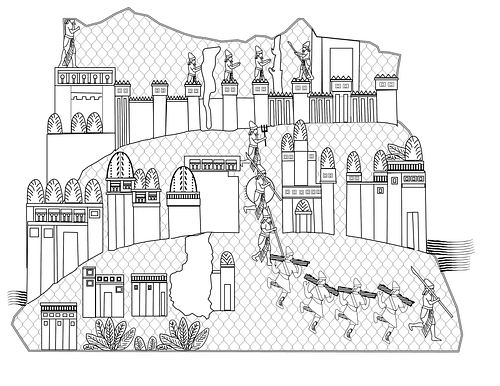

Another important aid in reconstructing the architecture of the Phoenicians is the fact that their cities were sometimes represented in contemporary Assyrian art, typically scenes of conquest, although the architecture may be schematic, of course. Examples are the bronze gates of Salmanassar III (859-824 BCE) from Balawat and the reliefs of Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) which show scenes of attacks on Tyre. Another source is a 4th-century BCE coin from Sidon. In these art forms, the cities are shown with impressive fortification walls with towers topped by decorative palm sculpture, and houses have multiple floors (perhaps up to six) with two columns outside their entrances.

Solomon's Temple at Jerusalem

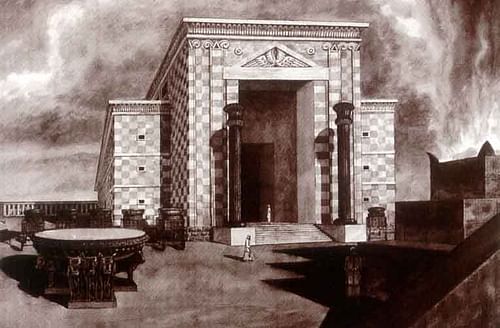

A helpful source of information on Phoenician architecture is the Bible's I Kings 6-7 description of King Solomon's temple. This was, of course, built at Jerusalem in the 10th century BCE but the architects and artists involved in its construction were Phoenician and its layout matches temple descriptions at Phoenician sites and the wider region. Its general design shows a significant influence from Egyptian architecture.

The rectangular temple had three inner chambers, each on progressively higher levels, with the rear two being connected by a short flight of steps. The third square room at the back was where the Ark of the Covenant was said to have been kept. The temple door was approached by a flight of steps and flanked by two columns, described in the Bible as bronze, by Herodotus as one made of gold and another of emerald. In front of the temple, in a sacred courtyard, was a set a huge bronze bowl described as a 'molten sea' because of its prodigious size and an altar for sacrifices and offerings. Destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th century BCE, there are no archaeological remains of the temple.

The Temple of Melqart at Tyre

The temple of Melqart at Tyre, of which no remains have been found, was built during the reign of Hiram in the 10th century BCE (the king built similar temples to Astarte and Baal Shamem too). It was described by Herodotus in Book 2:44 of his Histories. The 5th-century BCE Greek historian tells us that there were two columns at the entrance, made from the same material as those at Solomon's temple. The columns may each have been topped with a Proto-Aeolic capital (fore-runner of the Ionic capital and itself influenced by Egyptian architectural motifs) examples of which have been found on Cyprus and other Levant sites and which is considered a Phoenician invention. The flooring of the temple probably used alabaster slabs to create decorative patterns. Herodotus goes on to say that the god and mythical founder of Tyre Melqart had his tomb within the temple which also functioned as the city's treasury.

Unlike in later Greek and Roman temples, the Phoenicians seem not to have created large sculptural likenesses of their gods; the practice may even have been prohibited. Rather, at his temples, Melqart was represented by an eternal fire, a symbol of regeneration. Outside the temple was a specially constructed altar where worship of Melqart was performed involving prayers, burning incense, the pouring of libations, and making offerings to the god of animal sacrifices, foodstuffs, and precious goods. It is thought that the temple of Melqart at Phoenicia's most successful colony Carthage was very similar in design. Another temple at Gades (Cadiz) also had two columns at its entrance, this time made of bronze.

The Tophet & Tombs

The tophet was a large enclosure with a sacrificial altar and tombs for the cremated remains of victims. No archaeological remains survive of a tophet in Phoenicia itself but references in ancient sources and their presence in several Phoenician colonies would suggest there likely was such a place in each of the Phoenician home cities. Tophets were located outside and to the north of cities. Aside from the occasional infant sacrifice for which the Phoenicians have become infamous, animals were sacrificed and foodstuffs offered. Votive columns made from wood (aserah) or stone (betyl) were also placed upon sacrificial altars. These were inscribed with prayers and decorated in festivals with flowers and tree boughs.

Ashes from the sacrifices made at the tophet were placed in an urn. Stones were then placed on top of the funerary urns to seal them and placed within the tophet, sometimes within shaft tombs or dromos tombs built into a low hill-mound and accessed by descending steps. Shaft tombs, which were undecorated, could be quite large - several metres deep, and accessed by a vertical shaft or corridor. An example is the tomb of Ahiram at Byblos which has an entrance shaft, gallery, and chamber for the sarcophagus. In the later Persian dominated-era monuments were constructed above ground to mark the tombs. These are known as meghazils and consist of one or two cylinders topped by a dome or pyramid and with four lions at the base. From the 6th century BCE, stelae were dedicated to Baal or Tanit and placed on top of the funeral urns instead of stones. Many stelae have an inscription which describes a human blood sacrifice or the substitution of a sheep for a child.

Shrines

Unlike the larger buildings of the Phoenicians, many small shrines have survived at such sites as Sidon and Amrit. The 5th-century BCE shrine at Amrit was set in a large sacred precinct which was enclosed on three sides by a portico with square pillars. In the precinct was set a very large stone basin filled with water, in the centre of which was placed the cube-shaped chapel which had an open front and probably contained a cult figure or symbol. The chapel rested on a short column of blocks and platform and may have been topped with a solar disk. A second type of Phoenician shrine was at the 'high places' mentioned in the Bible which were merely dedicatory stelae set on a low base and found on mountain peaks.

Fortifications & Harbours

Other known structures built by Phoenician architects, besides the above mentioned, include large dams and bridges. For these structures huge stone blocks were used and their remains can still be found at the sites of Sidon, Tyre, and Aradus. Dependent as the Phoenicians were on sea-trade, they also constructed artificial harbours (cothons) consisting of rectangular docks carved out from the natural rock and accessed by narrow canals, of which surviving examples are best seen at colony sites, notably Carthage.

The city fortifications seen in Assyrian art are confirmed by excavations at Byblos, which have revealed massive ramparts punctuated by towers and gates. Dating to the middle Bronze Age these walls were constructed with stone foundations and mud-brick superstructures. There were also corridor-like gates which led to the sea, using stepped ramps. Similar fortification foundations have been excavated at Beirut and, on a smaller scale, at Tel Kabri.

Urban Housing

Surviving examples of urban housing are few and far between. In the Early Bronze Age, Byblos had oval houses and rectangular ones with rounded corners. In the Middle Bronze Age, there are large rectangular buildings dotted around the narrow streets of the city in no apparent pattern. These did not contain interior partition walls, and their purpose is unknown. In addition, there were silo buildings made in the shape of a bottle. Other smaller buildings show evidence of being paved with limestone and possess stone channels underneath for drainage. Within these domestic dwellings were ovens and basalt stones for grinding wheat. Buildings were constructed with carved stones and wood (olive, oak, and strawberry) or employed mud-bricks supported by dressed stones placed at corners. There is little evidence of town planning at Phoenician sites where local topography usually dictates the orientation of buildings.