The term Kabbalah refers specifically to the form of Jewish mysticism that became widespread in the Middle Ages. However, in recent decades it has essentially become a generic term for the entirety of Jewish mystical thought. Literally meaning "that which is received," the Kabbalah comprises a series of esoteric traditions dating back to biblical times and is still very much alive today. It deals with subjects such as the creation of the world, the nature of God, the ecstatic mystical experience, the coming messianic era, and the nature of the afterlife. Ultimately, the Kabbalah represents the Jewish form of what all mystical traditions strive for; a direct and intimate knowledge of the divine on a level beyond that of the intellect.

Though essentially a tradition of esoteric knowledge, Kabbalah was popular and widely practiced until the dawn of the modern era, though there were restrictions placed on the age and relative piety of initiates. It comprised ancient Talmudic explorations of biblical subjects, tales of ecstatic descents to the throne of God, vast myths of the creation of the world, intense messianic fervor, and forms of pietistic ritual and practice that gave birth to movements that still influence Judaism today.

In the wake of the haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, the Kabbalah came to be regarded by many Jews as at best an embarrassing relic of a more credulous time, and it fell into great disrepute among the newly secular Jews of Europe. Recently, however, the Kabbalah has experienced an enormous revival, with widespread secular and religious interest in it, and some schools reaching out to non-Jews in an unprecedented way.

Biblical Origins

There is no systematic form of mysticism mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, though forms of magic and divination abound. For example, Moses performs magical feats such as turning a staff into a snake, figures such as Jacob have visions of the divine, and King David dances in an ecstatic trance as he enters Jerusalem. Indeed, the entire tradition of prophecy, which entails the channeling of divine speech, could be viewed as a mystical exercise.

The most important mystical subject in the Bible is Ezekiel's vision of God's throne-chariot. Its surreal, cryptic, and in some ways dangerously anthropomorphic imagery led to passionate exposition and exegesis that eventually gave birth to one of the two main subjects of the early Jewish mystical tradition; the maaseh ha'merkabah or "work of the Chariot." The other primary subject of early mystical speculation is also contained in the Bible: the creation of the world itself, the mysteries of which came to be called maaseh bereshit or "work of the beginning."

Talmudic & Merkabah Mysticism

The first form of recognizably systematic Jewish mysticism likely emerged in the Second Temple period and appears to have taken on its complete form by the Talmudic era. It is based on Ezekiel's vision, which had already become the subject of intense mystical speculation. The Talmud itself speaks of certain rabbis expounding the 'secrets' of God's chariot, though the secrets themselves are not revealed. These passages also hint at strong prohibitions on revealing such secrets in public or writing them down. It appears that they could only be transmitted orally to small numbers of students already knowledgeable in Jewish law and theology.

These restrictions are obliquely explained in the famous story of the four who entered the garden, a tale of four rabbis who behold a divine vision: one died, one went mad, one became a heretic, and one emerged 'in peace'. This was interpreted as a parable of the dangers of mystical visions of the angels and God's divine court.

While it is not clear if these tales reference a specific mystical tradition, it seems likely that they do as what has been called "merkabah mysticism" by modern scholars emerged around this time. This form of mysticism involves the descent through ecstatic meditation into the seven halls of the divine palace, ending in visions of God's court and his throne-chariot. Prominent rabbis were referred to as practicing this form of mysticism, and a prodigious literature regarding these journeys was collected.

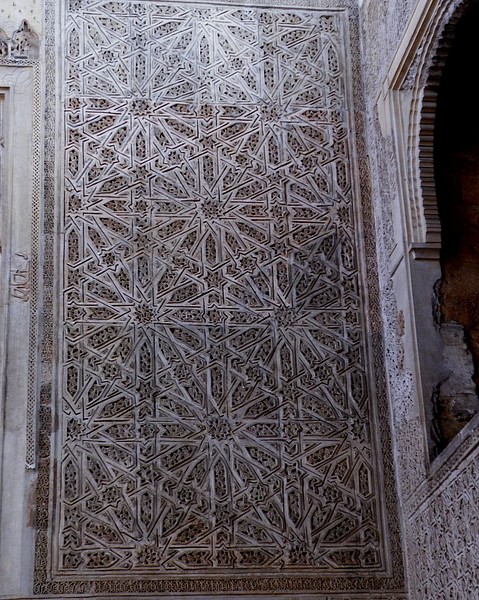

Sefer Yetzirah

The first work of literature that can be accurately described as proto-Kabbalistic in the formal sense is the Sefer Yetzirah or "Book of Creation." The time of its writing remains controversial, though it is likely post-Talmudic and unquestionably existed by the 10th century CE. Unlike its predecessors, the Sefer Yetzirah does not deal with the divine chariot, but rather the creation of the world. The extremely short and often highly cryptic text describes the creation as taking place through God's incantation of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet with the collaboration of ten sefirot (sephiroth) or "numbers," which are given vaguely anthropomorphic form.

As such, the Sefer Yetzirah marks the beginning of the Kabbalah as it is known today. Though it was eventually superseded by medieval works of much greater sophistication and length, the Sefer Yetzirah led to extensive mystical and philosophical speculation and appears to mark the first widespread and generally accepted form of systematic mysticism in the Jewish world.

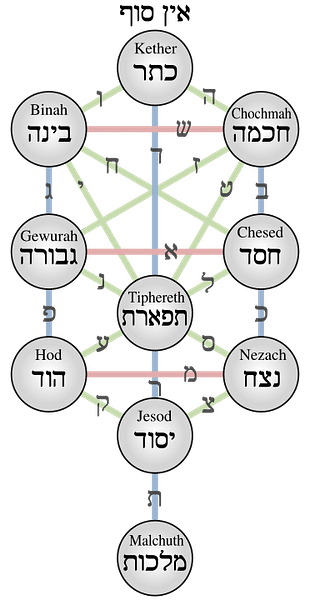

The Sefer Yetzirah was succeeded by the lesser-known but still essential Sefer HaBahir or "Book of Brightness." Also short and even more cryptic than its predecessor, the Bahir nonetheless expanded the concept of the sefirot by conceiving of them as vessels for divine energy that reflected specific aspects of the Godhead as manifested in the "lower" worlds. The combination of the two books would lead to the creation of the canonical Kabbalistic text the Sefer HaZohar.

The Zohar

The monumental Sefer HaZohar or "Book of Radiance" is the single most important text of the Kabbalah. The origins of the Zohar were initially unclear and aroused considerable controversy at the time. It emerged in the 1200s CE and was attributed to the ancient rabbi Simeon Bar Yochai, though modern scholars largely agree that it was primarily written by Moshe de Leon, a Spanish mystic, and/or a group of similar-minded mystics whose speculations were eventually collected and published by de Leon.

A massive work of well over 1,000 pages in printed editions, the Zohar is written in a pseudo-Aramaic dialect and proposes a far-reaching, epic cosmology that set the standard for Jewish mysticism in the ensuing centuries. Among its key concepts is that of the Tree of Life: the configuration of ten sefirot, which are conceived of as spheres or entities composing the various attributes of God. These sefirot are separate from the infinite unknowable essence of God, called the ain sof or literally "without end." They are identified with specific divine characteristics such as bina ("wisdom" or "understanding"), hesed ("mercy"), and gevurah ("strength"). At the same time, they represent parts of the divine body, such as hands and feet.

Most strikingly, the Zohar's cosmology contains an explicitly erotic element, with the sefirot of yesod ("foundation") and malchut ("kingship") representing the penis and vagina respectively, making God an intersex being who engages in a form of creative auto-eroticism, a concept that remains essential to later forms of Kabbalah. Equally important for later forms of Jewish mysticism was the idea that what transpires in the material world directly influences the divine world and vice versa: "The impulse from below calls forth that from above" (Zohar I, 164a). This gives humanity a highly active role in the work of the divine, influencing the world of the sefirot through study, religious ritual, prayer, and mystical practices.

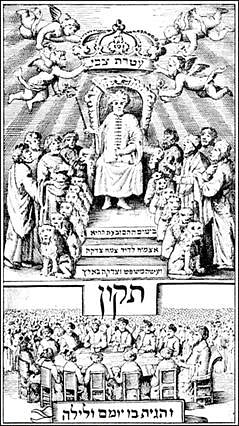

Although not as emphasized as it would be in later Kabbalah, the Zohar also contains nascent messianic elements, with the idea that there exists a flaw in the divine architecture as a result of human sin and the ongoing exile of the shekhina and the people of Israel, which can be repaired through the messianic tikkun ("repair"). This tikkun can be aided by fulfilling the Jewish commandments, engaging in good works, and studying the Torah. Such messianic concepts would be seized upon by de Leon's successors to the point that they became central to Jewish mysticism over the next several centuries.

The Ari

The Zohar quickly spread throughout the Jewish world and revolutionized the thought and practice of Kabbalah. Several attempts were made to form a coherent, systematized mystical tradition from its often obscure teachings, but by far the most successful was that of the 16th-century CE rabbi Isaac Luria, also referred to as the Ari ("the lion").

Luria, of mixed Ashkenazi and Sephardi heritage, thus uniting the two most important schools of Judaism and their mystical traditions, made his mark in a circle of Kabbalists based in the town of Safed in the eastern Galilee. Luria based his mystical system on the Zohar but included original teachings he claimed to have received directly through spiritual discourse with the souls of long-dead mystics buried in the area. He left almost no writings of his own, but his teachings were written down by several of his students, most notably Haim Vital, who published the most influential version of them.

Vastly simplified, Luria's Kabbalah proposed that at the moment of creation, the infinite God of the ain sof contracted himself in order to create the space in which the world would be created. This was referred to as tzimtzum ("contraction" or "reduction"). Flowing into this space were the vessels of the sefirot and a beam of divine light. Unable to contain this divine energy, the vessels shattered, creating the klippot or "shards" that make up our corrupted material world. Remaining in this material realm, however, were "sparks" of the original divine light. This dark vision of the world's creation was then linked to the concept of galut ("exile"). Luria posited that not only was the Jewish people living in exile, but also God's indwelling in the shekhina and, to an extent, God himself and all his creation.

It is at this point that Luria's Kabbalah takes on a profoundly messianic quality. Using the Zohar's concepts of tikkun and the raising of the divine "sparks" through a mystical tradition and religious study and ritual, Luria proposed the emergence of a messianic era in which the messiah's soul would reach the fulfillment of its travels through the many cycles of reincarnated existence, called the gilgul ("cycle"). The incarnated messiah would then raise up the final sparks, thus completing the repair of the shattered material world, which will be dissolved into the spiritual world, repairing not only creation but also God himself. Luria's Kabbalah proved even more successful than that of the Zohar, capturing the deep longing for redemption across the Jewish world. Its intense messianism, however, profoundly disturbed traditional Judaism, which had long sought to tamp down rather than encourage messianic emotions.

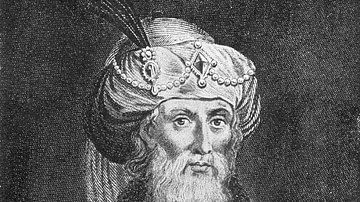

Sabbatai Zevi

The messianic fervor aroused by the popularity of the Zohar and Lurianic Kabbalah eventually coalesced around the figure of a Turkish mystic named Sabbatai Zevi (Shabtai Tzvi). Wildly charismatic and possibly mentally ill, Zevi became the most successful false messiah since ancient times. Born in 1626 CE in Izmir, Zevi became well-known in local Jewish circles for his charisma and Kabbalistic knowledge, but also for unbalanced and sometimes openly offensive behavior. It appears that Zevi was often seized by heights of ecstatic emotion, at certain points declaring himself the messiah. After these attacks, he would collapse into dark and introspective moods in which he would profoundly regret his previous public actions. He was eventually expelled from the local Jewish community for his behavior.

In 1663 CE Zevi traveled to the land of Israel, where a young and gifted thinker named Nathan of Gaza proclaimed him the promised messiah. Already prepared for such a figure by Lurianic mysticism, much of the Jewish world enthusiastically embraced the new object of their hopes and pledged their fealty to the new messiah. Eventually, Zevi was arrested and imprisoned by the Ottoman authorities, and the Turkish Sultan presented him with an ultimatum: death or conversion to Islam. Zevi chose the latter, shattering his followers' faith in him. Though most of the Jewish world reacted with shock and crushing disappointment to the supposed messiah's apostasy, small groups of adherents continued to follow him.

Nathan of Gaza remained loyal and developed a theology in which the messianic soul - i.e. Sabbatai Zevi - had to descend to the lowest level of the Lurianic klippot in order to raise the final divine sparks and bring about the tikkun, thus explaining Zevi's apostasy. This doctrine has come to be called ha'mitzvah sh'baah b'averah (lit. "the commandment that comes in its transgression") or what leading scholar of the Kabbalah Gershom Scholem called "redemption through sin." Some Sabbateans followed Zevi by converting to Islam while practicing his doctrines in secret. One such sect, the Donmeh, still exists today.

Hasidism

In the wake of Sabbatai Zevi's apostasy, the messianic idea was once again suppressed, though Lurianic Kabbalah itself remained popular. Its final incarnation as a mass movement and one that proved far more successful than its predecessors, Hasidism or Hasidic Judaism was ostensibly founded by an 18th-century CE itinerant mystic and faith-healer who came to be called the Baal Shem Tov ("owner of the good name"). Somewhat in the fashion of a Zen monk, he traveled the large Jewish communities of Eastern Europe preaching a pietistic and populist doctrine that emphasized an immediate emotional experience of God as opposed to what he saw as the dry legalism of the traditionalist establishment. He emphasized the ecstatic joy of celebration and the ideal of devekut ("cleaving to"), i.e. the conscious emotional channeling of prayer and ritual into a direct mystical connection with God. Rather than solemnity, Hasidism emphasized joy and emotion as well as the ability of every Jew to achieve the highest level of spiritual enlightenment and ecstasy, rejecting the idea of a rabbinical or mystical elite.

The Baal Shem Tov began to gain large numbers of followers, who organized themselves into schools or rabbinical courts based in specific Jewish communities. The most prominent of them came to be referred to as tzaddikim ("righteous ones"). While the tzaddik was similar to the traditional role of the rabbi in the sense that he was a teacher and leader of the community, he also took on a new aspect as the direct conduit of the divine to his followers. Though none of the tzaddikim claimed to be messiahs themselves, the messianic aspects of the Zohar and Lurianic Kabbalah remained strong. In particular, Hasidism adopted the ideas of the klippot, the tikkun, and the divine "sparks" as essential to its theology. Through the ecstatic experience, adherence to the law, and the devekut of individual prayer, the Hasidim believed that the repair of the broken vessels and redemption of Israel and the world could be achieved.

Hasidism proved to be an enormously popular movement, though it aroused profound hostility among the more traditionally-minded, who came to be called mitnagdim ("opponents"). While its numbers were decimated in the Holocaust, Hasidism proved to have remarkable regenerative powers, and its centers in the United States and Israel have shown enormous growth in recent decades.

Modern Kabbalah

In the modern age, the Kabbalah has gone through successive cycles of popularity and widespread rejection. When the haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries CE, the Kabbalah was derided as absurd and slightly embarrassing by the emerging secular and rationalist movements in the Jewish community. By the 20th century CE, however, the Kabbalah had come to be seen as an important religious, theological, and sociological phenomenon in Jewish history, and the academic study of it came into its own with the works of Gershom Scholem, Moshe Idel, and many others.

On a popular level, aspects of the Kabbalah remain widely practiced today by traditionally-minded Jews. This sometimes involves the use of magical amulets and the singing of Kabbalistic liturgy, most famously the mystical hymn "Lecha Dodi." Many Jews observe such practices while remaining largely ignorant of the mystical ideas behind them. While the messianic idea remains alive, it is far less widespread in the Jewish community.

Perhaps most remarkably, a movement has also emerged that for the first time teaches a form of Kabbalah to non-Jews. The Kabbalah Centre has become famous due to members such as Madonna and preaches a syncretic combination of traditional Kabbalah and New Age thought that has proved surprisingly popular among those who have no other connection to Judaism whatsoever. Given today's fascination with various forms of mystical thought, secret knowledge, and the Kabbalah's remarkable historical malleability, it seems likely that it will continue to play an enormous if sometimes overlooked role in Jewish thought, practice, and spirituality for the foreseeable future.