War was the chief means by which territory was annexed or rulers defeated in ancient India, which was divided into multiple kingdoms, republics and empires. Often one empire predominated or different empires co-existed. The Vedic literature (1500 – 1000 BCE), the two epics Ramayana and the Mahabharata (1000 - 600 BCE), Kautilya's Arthashastra (c. 4th century BCE) and Banabhatta's Harshacharita (c. 7th century CE), all key texts regarding warfare in ancient India, testify to this. Troops were recruited, trained and equipped by the state (maula). There were many communities and forest tribes (atavika) that were known for their military skills and prized as such. Such people lived by the profession of arms (ayudhjivi). Villages providing soldiers were called ayudhiya. Mercenaries (bhrita) also existed in large numbers as did corporate guilds of soldiers (shreni) and they were recruited whenever required.

Attitudes to Warfare

The king or emperor was supposed to be a great warrior, capable of vanquishing enemies on the battlefield and subduing their kingdoms. The idea of digvijaya (Sanskrit: “victorious campaign in all directions”) so that a ruler could become a chakravarti samrat (Sanskrit: “emperor whose chariot wheel rolls unobstructed”) was always emphasized. Religiously, the Hindus favoured war as a means of furthering royal ambition and even advocated the concept of dharma yuddha or “just war” to avenge injustices or claim one's justified right to the throne. Buddhism and Jainism, despite their advocacy of non-violence, also understood the role of war and warfare in the prevailing political system and especially for the defence of one's kingdom against invaders embarked on a digvijaya. The Buddha himself advised the minister of Magadha's king Ajatashatru (492 - 460 BCE) on how difficult it would be to conquer Vaishali. Alongside all his humanitarian work, the Mauryan emperor Ashoka (272-232 BCE) also did not disband his army but continued to maintain efficient means for the security of his people, which he considered as part of his duty as a Buddhist ruler looking after the welfare of his subjects. Throughout the ancient period, many of the most notable emperors, kings, warriors and even individual soldiers continued to be devout Jains.

The Ancient Indian Army

The army was composed of four arms (chaturanga)—infantry, cavalry, chariots and elephants. They were all deployed in the field of battle in formation (vyuha), as decided by the commanders, based on factors such as the nature of the terrain and the composition of one's and one's enemy's forces. Great concern was shown to the training of men and animals. The kings and princes were well-trained in the arts of war and leadership, personally led armies and participated in the defence of forts.

Wooden battle chariots (sangramika) were used as command vehicles and prized for their mobility as they could carry archers who could shoot while moving throughout the battlefield. Yoked with two or even four horses, these vehicles could easily mow down enemy infantry but could be used only in the plains and not for surprise attacks. Thus beginning around 6th century BCE, elephants replaced the chariots as the elite arm. They were considered as being invaluable owing to their huge destructive power. They acted as command vehicles and provided shock value, i.e., the psychological impact on the enemy. The practice of intoxicating elephants led them to cause much panic and loss of both enemy morale and numbers. Their other functions included clearing the way for marches, fording rivers, guarding the army's front, flanks and rear and battering down fort walls.

The infantry was the largest in number and it was only towards the end of the ancient period that cavalry came to occupy some position of importance, especially under the Rajput rulers in north, central and western India, who used camels as well. In south India, the climate was not conducive to the breeding of horses but of elephants, and hence the dynasties there focused on elephants, infantry and the navy.

The Ancient Indian Battlefield

Despite the vyuhas, once the battle began, the fighting would become general. The infantry would bear the brunt of the fight, attacked mercilessly by chariots, elephants and cavalry. The infantry did not fight in compact formations like the Greek or Macedonian phalanx and hence could easily be scattered and targeted. The main aim was to rout the enemy troops and kill the king or commander, as that would lead to his men fleeing and thus decide the day. Commanders and other chief leaders rode chariots and later, elephants.

Fighting could take place on low grounds, in open battle, ambuscades (sattra), under the cover of entrenchment (khanakayuddha), from heights (akasayuddha) and even during the night. The chief commander could order the advance or retreat (ayogamayogam cha) and marshalled the units by assigning trumpets, boards, banners, or flags.

The footsoldiers fought also in forests, hilly and inaccessible regions. The cavalry fought as a body on the battlefield and was used for cutting off provisions and reinforcements of the enemy, scouting and reconnaissance, charging the enemy especially at the flanks and the rear, protecting other units of the army and covering advances and retreats and pursuing the retreating enemy.

Weapons

Arms included bows and arrows, swords, double-handed broadswords, oval, rectangular or bell-shaped shields (often of hides), spears, javelins, lances, axes, pikes, clubs and maces. Bows were the primary weapon for the infantry, chariot and elephant warriors and even the commanders. One type of bow was peculiar to the Indians—it was of equal length with the man who bore it, which he rested on the ground and pressed one of its ends with the left foot before releasing the arrow. The cavalry carried two lances and a buckler (round shield), smaller than the infantry one.

Armour

Soldiers were either generally bare to the waist or wore quilted cotton jackets. They also wore thickly coiled turbans, often secured with scarfs tied below the chin, and bands of cloth tied across their waists and chests as protective armour. Tunics were worn during winters. The lower garment was a loose cloth worn as a kilt or in the drawer style, with one end tucked in at the back. The cavalrymen used trousers.

From the Gupta period (3rd century CE to 6th century CE) onwards, the soldiers mostly abandoned the turban and wore the hair loose, with tunics, crossed belts on the bare chest or a short, tight-fitting blouse. The elites commanding the army or other officials wore armour (especially of metal). Other classes of crack troops were similarly well-furnished.

Armour included helmets, turbans, covers for neck, torso, sleeved/sleeveless coats of varied length, wrist-guards and gloves. There was also armour made from hides, hoofs and horns of certain animals like tortoise, rhinoceros, bison, elephant or cow or chainmail.

Command Structures

The emperor or king was always the supreme commander, followed by the crown prince (yuvaraja) and the general or commander-in-chief (senapati). Below that were the superintendents of the various arms known as rathadhyaksha (for chariots), gajadhyaksha (elephants), ashvadhyaksha (cavalry) and patyadhaksha (infantry) and admirals (navadhyaksha), in case of the navy. In some kingdoms, however, the cavalry and elephants consisted of a single division. Units and ranks below that varied across kingdoms and empires, and across different time periods. Mainly, the terms used for senior commanders were mahadandanayaka or mahabaladhikrita, followed by dandanayaka or baladhikrita, nayaka and gulmin. Soldiers comprising a company were called gaulmika. The chief ministers also occasionally marched with the army. In the Magadha kingdom, a body of officials known as mahamatras ran the department of war.

Fortifications & Siege Warfare

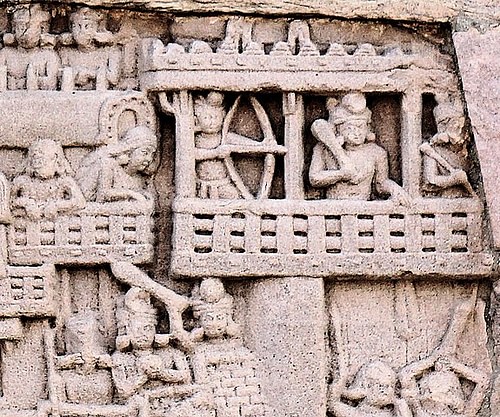

Forts held a key position in ancient Indian warfare. They were required not only for the security of the populace that lived in its vicinity, but the kingdom as a whole as it provided shelter to the king and his armies against enemies and checked the invaders from advancing further into the kingdom. Capturing forts was necessary as most often, enemy capitals were usually fortified and no invader could proclaim victory till he had captured these strategic strongholds. Forts were also treated as centres for administrative units. They were built in border regions, at the extreme ends of the kingdom, and in different terrains—islands (forts known as audaka), hills (parvata or giridurga), deserts (dhanvana) and forests (vanadurga).

There were moats, ramparts, parapets, towers, turrets and positions for archers, passages for flight and exit doors along with multiple gates, secret land ways and waterways. The forts were also well-stocked with the number and amount of resources necessary for withstanding long sieges, such as food and weaponry.

There were garrison troops specializing in defence of forts. Assaults were generally made by elephants (purabhettarah). Archers played a huge role in both attack and defence. The stress was on a general assault, making entry by breaking open the gates after crossing the moat, or by inducing the enemy to come out for a sally. An assault was considered best at a time when the enemy was tired after fighting either on the walls or in an open battle and had thus lost many of its men, while the general public inside the fort would be generally distracted. Weather conditions also determined the day of the assault.

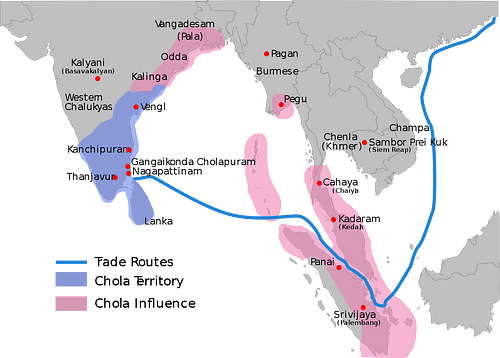

Naval Warfare

The navy was used to transport troops to distant battlefields, participate in actual warfare and was primarily meant for protecting the kingdom's trade on sea and navigable rivers and the maritime trade routes by destroying pirates. The warships were used in battles which, as compared to land battles, remained low in proportion. The ancient Indians preferred to fight on land and fights on sea were not given much importance, except in a few cases where destroying the enemy navy became crucial. The ships were mostly used to conquer islands, as has been presumed for the campaign of the Gupta emperor Samudragupta (335 CE – 380 CE), or for fighting seafaring peoples as the Satavahanas ( 1st century BCE – 2nd century CE) did.

Dynasties in the western, southern and (coastal) eastern parts of India, situated on the sea coast, relied heavily on maritime trade and the sea and built navies that were used in war. It was in these parts and the adjacent high seas that ancient India saw most of its naval warfare in practice. The most compelling reason was that to capture the highly lucrative foreign trade of the enemy, it was necessary to destroy his navy that protected it. Wars with Sri Lankan kings made the southern dynasties add to their navy. The Cholas (4th century BCE to 13th century CE) conducted expeditions even to Southeast Asia.

The ancient Indians had a good knowledge of the materials, varieties and properties of wood which went into the making the different classes of ships. The Yuktikalpataru of King Bhoja (c. 1010 CE –1055 CE) of Malwa, the only ancient Indian work dealing in detail with the subject of shipping, mentions a kind of vessel called agramandira which had its cabins towards the prows and was thus seen as being suitable for naval warfare (rane kale ghanatyaye). Ships were single, double or triple-masted. The number of oarsmen depended on the size of the vessel and the warriors who went into combat.

No direct references are available as to how naval battles were actually conducted. It is likely that the ships or boats carried warriors who were equipped with the standard-issue weapons of the period like swords, javelins, maces and spears. The archers would have been more heavily involved in the fighting, especially by shooting fire arrows. As soon as the enemy ships or boats would have come in range, soldiers of both the sides would have engaged in hand-to-hand combat and attempted to jump onto the enemy vessel in order to kill as many of the enemy and destroy it, and then return (if still alive) to their own ship/boat. The main aim was to destroy the enemy ships, accomplished by breaking the ships or setting fire to them. Some kind of contraption would be on-board to pelt stones on the enemy ships so as to smash them.

Strategies of War

Strategies were both defensive and offensive. The ancient Indian thinkers insisted on war as a means for increasing royal glory and outright conquest. Offensive strategies were thus devised which could allow the conqueror's army to traverse large distances and either overawe the adversary into submission, or to defeat him on the battlefield if he chose it that way. Different armies would be stationed in different directions to deal with enemies in the concerned area.

Defensively, the ancient Indians would not pre-empt any threat from outside invaders. Even while fighting Macedonians, Greeks, Scythians, Huns and later the Turkic invaders, the Indians would continue with their own war system till defeats proved that changes were necessary. Even then, changes would be necessitated only if the king or a strategist had the vision and realization to do so, otherwise, the enemy was challenged in the time-honoured way, even if that meant continuous defeats. Changes to the military system, whenever introduced, would not last and the succeeding kings or generals would lapse back to traditional systems. Although the ancient Indians had dealt with Scythian and Hunnic horse archers in fifth-eighth centuries CE, the lessons were not learnt and when they were encountered again under the Turkic generals in 1192 CE,

The Rajput valour proved of no avail against these mounted archers and a fearful carnage ensued on all sides. The Hindu generals had profited little by their past experience and did not understand the efficacy of a mobile cavalry in dealing with their enemies. The result of the battle was a foregone conclusion.

(Prasad, p. 137)

The array in which elephants were at the front, chariots at the flanks and horses at the wings was believed to be the best formation to break the centre of the enemy's army. The strategy of using elephants as the primary arm had its drawbacks. The moody beasts, despite all the training, did more harm than good—they trampled upon their own troops, ran amok, and could even carry the commanders riding them away from the battlefield, which could be interpreted as flight, making their soldiers panic-stricken and flee, or they could simply give up the fight. Being at a height, the commander himself was a sitting duck and could easily be targeted by enemy soldiers. In many cases, the royal elephant was expressly targeted for the same purpose.

War by Other Means

Besides contesting on the battlefield, emphasis was laid on covert operations, on breaking the enemy's morale, sowing dissension among his ranks, causing rebellions, conspiracies, breaking of alliances and assassinations of kings or leaders. Such kinds of war were called as gudayuddha (Sanskrit: “clandestine war”) and kutayuddha (Sanskrit: “concealed war”). Assassins, spies and saboteurs thus played a huge role. Magadha's war with Vaishali (484 – 468 BCE) and the rise of Chandragupta Maurya (321-297 BCE) saw such developments. Vivid details of the latter are given in the Sanskrit drama Mudrarakshasa written by Vishakhadatta (presumably 5th century CE).

Logistics

The vast distances that characterized ancient India (which then included the present countries of Pakistan and Bangladesh as well) made the movement of armies across vast tracts difficult. It was equally difficult to provide for armies going very long distances, hence, in most cases, logistics played a key role in determining the nature and duration of the campaigns, which would be generally towards areas geographically close to one's kingdom. In other (rare) cases, if the sovereign was intent on a distant campaign, efforts would be made to ensure provisions and a secure march.

The armies were well provided for and officials were appointed to look after the various needs of the army on the march as well as in camp. The provisions, which included food, fodder, weapons, clothing and camping materials, would be carried on bullock carts, elephants, mules and camels and accompany the army. Often, such processes could be very chaotic. Technically, the cultivators, merchants and villagers were to be left alone, but often in practice, the soldiers would plunder the grains or merchandise, in which case complaints of the aggrieved could be put before the king who was supposed to take action. Supply depots were maintained especially under the Mauryans. A medical corps also existed composed of physicians and surgeons with surgical instruments and medicines. The provision of supplies for the army of the Samudragupta which marched across nearly the whole country, was a feat indeed.

Big Victories & Losses

- Magadha under Ajatashatru won the 16-year long war with Vaishali (484 – 468 BCE) by using both covert means and military innovations like the rathamusala (a chariot with a mace attached, causing much mayhem) and the mahashilakantaga (a siege engine resembling a huge catapult).

- Battle of Hydaspes (326 BCE): King Porus (Sanskrit: Puru or Paurava; Greek: Poros) (c. 4th century BCE) met a disastrous defeat at the hands of Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE).

- Battle of Takkolam (949 CE): The Cholas were utterly routed by the Rashtrakutas (8th century CE to 10th century CE) and their vassals and the Chola crown prince Rajaditya (c. 10th century CE) was killed on his elephant.

- Battle of Tarain (1192 CE): Effectively employing horse archers, the Turkic armies of Shahabuddin Mohammad of Ghur (1173-1206 CE) destroyed the Rajput armies of Prithviraja III Chauhan (1178-1192 CE), the last Hindu ruler of Delhi-Ajmer, and thus paved the way for the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate. Prithviraja was captured and killed.

- Naval Battles: The Vatapi Chalukya king Pulakeshin II (609 CE – 642 CE) destroyed the navy of the Konkan Mauryas off the coast of Elephanta island (near present-day Mumbai, Maharashtra state) in 635 CE. Raja Raja I Chola (985 CE - 1014 CE) destroyed the fleet of the Later Chera/Kulashekhara king Bhaskara Ravivarman I (962 CE – 1019 CE), off Kandalur Salai (modern day Valiasala, Kerala state), by killing enemy warriors, splitting in two a naval vessel belonging to their king and destroying a number of boats (or ships).